Specialization Not the Only Pathway

April 21, 2015

By Eric Martin

By Eric Martin

MSU Institute for the Study of Youth Sports

Specialization is not a new topic facing athletes and parents.

In a 1989 study by Hill and Simons, athletic directors indicated that the three-sport athletes of the past were being replaced by athletes who only participated in a single sport. Multiple athletic directors indicated that the decrease of multi-sport participation was a concern for all involved in the sport environment as increased emphasis on sport specialization was not in the true vision of high school sports.

Even though the distress concerning sport specialization is not a new topic, the rise of club sports and year-round travel teams have increased the number of youth athletes who are forced to make a choice between playing multiple sports or focusing their time and training efforts solely on one sport. The decision to focus solely on one sport sometimes is done by athletes (or their parents) who believe that quitting other sports is the sole way to earn a coveted college scholarship.

However, even though counter intuitive, sport specialization may be hampering their pursuit to play at the next level.

Elite level achievement in sport is rare, with statistics showing that only 0.12 percent of high school athletes in basketball and football eventually reach the professional level. To combat these odds, many in popular media including Malcolm Gladwell have forwarded Anders Ericcson’s proposal that to become an expert in a field, an individual must accumulate 10,000 hours of practice.

To achieve this aim, many parents and athletes disregard other sports believing that extra exposure to a single sport may result in accumulating these hours quicker and increase an athlete's chances of elite skill achievement. Reducing the achievement of sport excellence to solely practice hours overlooks the importance that developmental, psychosocial, and motivational factors play in the achievement of high level success in youth. Further, several research studies have found that elite athletes typically fall short of this 10,000 hour milestone.

Simply accumulating a magic number of hours does not guarantee sport success, and in fact, trying to accumulate these hours too early can lead to many different negative outcomes for youth.

Sport specialization has been shown to have a variety of negative physiological and psychological outcomes for youth athletes. Typically, athletes who specialize in one sport play that sport year-round with little or no offseason. In these cases, athletes who continually perform repetitive motions such as throwing or jumping can experience overuse injuries that can range from tendinitis to torn ligaments.

In addition to the increased risk of injury, youth who specialize and play a single sport year-round are at risk for psychological issues as well. Youth who play a single sport are less likely to allow for proper recovery and face the increased chance of burnout or decreases in motivation that may result in leaving sport entirely. Additionally, as practice time demands and multiple league involvement increases, youth may feel added pressure to succeed due to the increased time and financial costs incurred by parents.

Finally, youth who specialize early in only one sport do not develop the fundamental motor skills that help them stay active as adults, instead only developing a very narrow skill set of a single sport.

If the dangers of sport specialization do not encourage multisport participation, a majority of studies have shown that sport specialization does not increase long-term sport achievement. In fact, most studies indicate that athletes who reach the highest level of sport achievement typically played a variety of sports until after they were well into high school.

For example, a study with British athletes found that youth who played three or more sports at the ages of 11, 13, and 15 had a significantly higher likelihood of playing on a national team at ages 16 and 18. These athletes had a more rounded set of skills, were more refreshed for their chosen sport, and were more psychologically and emotionally ready to perform due to their experiences in a number of sports.

A study recently conducted by the Institute for the Study of Youth Sports with collegiate athletes showed similar results as the British athlete study. In the ISYS study, 1,036 athletes from three Division I universities were asked to report their past youth sport participation. On average, youth participated in three or more sports in elementary and middle school. The number of sports youth participated in decreased with each year of high school, but even with the decrease of participation, a larger number of individuals played more than one sport during every year of high school including senior year than those who played a single sport.

Even though a majority of athletes did play at least two sports throughout high school, several athletes did indicate that they specialized in one sport indicating that there are multiple pathways to elite sport achievement.

Athletes were also asked for their perception of how important it was to specialize in one sport in order to earn a college scholarship. On a scale of 1-9, athletes felt that specializing in one sport prior to high school was neither important nor unimportant (4.97).

Sport specialization is not a new issue, but that does not minimize the damage that can occur if athletes are overtaxed early in their development. Each athlete is unique, and each situation requires care. If an athlete does decide to play in only one sport, the decision should be made in regards to the athlete’s interest and development, not just in the pursuit of a college scholarship. Additionally, if athletes specialize in one sport, it is critical to understand that youth are developing and proper recovery is critical both physically and psychologically.

Early specialization in sport is an issue that is not going to go away, but for coaches, parents, and athletes this decision should be made with a long-term perspective and with the athletes’ long-term well-being central to the choice.

Martin is a fourth-year doctoral candidate in the Institute for the Study of Youth Sports at Michigan State University. His research interests include athlete motivation and development of passion in youth, sport specialization, and coaches’ perspectives on working with the millennial athlete. He has led many sessions of the MHSAA Captains Leadership Clinic and consulted with junior high, high school, and collegiate athletes. If you have questions or comments, contact him at [email protected].

Over 2 Eras, Boys Gymnastics Vaulted Into MHSAA History

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

April 14, 2021

Williamsburg, Michigan, and the shore of Elk Lake, seems an unusual spot to serve as an epicenter. Especially for something like gymnastics.

But during the late 1950s, it was exactly that.

“LOOK MA, I’M FLYING” was the title of an Aug. 5, 1957 Sports Illustrated article detailing the happenings at Charlie Pond’s National Summer Palaestrum.

“At Elk Lake, Mich.,” wrote SI, “exhilarated youngsters have learned to leap, jump and fly through the air with the greatest of ease at the National Summer Palaestrum, a gymnastic camp devoted from June to August to developing physical skills among boys and girls from 8 to 18. The enrolled campers concentrate on tumbling, trampoline, free exercise, apparatus work and balancing under Charlie Pond, the University of Illinois gymnastic coach with a penchant for developing fine, coordinated bodies. ... The camp accommodates 120 youths in each of four two-week periods.”

“His frame,” stated Al Barnes in the Traverse City Record-Eagle in 1958, “is somewhat slight and his blond, brush-cut hair leads you to think of him as, possibly, a professor of archaeology. But at his spacious summer camp on Elk Lake, about 14 miles northeast of Traverse City, (Pond) is one of the kids. He is as much at home on a trampoline as his more youthful understudies and he can do his stint on the high rings or the uneven parallel bars.”

Pond took over as head coach of the University of Illinois men’s gymnastics team in 1949. Between 1950 and 1958, his teams had won nine straight Big Ten titles (the streak would extend to 11 consecutive) and four NCAA national titles (outright wins in 1950, ’55, ’56, then a tie with Michigan State in 1958).

Pond’s first Elk Lake Palaestrum was hosted in 1956. A Chicago Tribune advertisement indicated it ran from June 18 to August 12.

“The establishment of a summer gymnastics palaestrum had been a dream for Pond for many years. ‘When I saw the Elk Lake Inn property,’ (Pond) said, ‘I knew that was it and I had to have it. It was ideally located and the climate in this area is excellently adapted for an outdoors activity.’”

By the 1958 season, the Palaestrum included options for two-week courses as well as day camp instruction. Public open house events were hosted to showcase activities. Children facing disabilities visited the camp and were encouraged to try the various equipment. That year the Palaestrum added a spectacular season-ending demonstration for the public, hosted at the Traverse City St. Francis gymnasium. The following year, the show was christened the “Night of Stars.”

Pond’s annual gathering was staffed by the top names in college gymnastics, including his clinic director, Michigan State coach George Szypula, plus University of Michigan’s Newt Loken, Georgia Tech’s Lyle Welser, Bill Meade from Southern Illinois, and Dr. Eric Hughes from the University of Washington among others, as well as numerous university and Olympic athletes who enjoyed the opportunity to perform, train and teach in a beautiful setting.

The Report That Shocked the President

Featured on the cover of that 1957 SI was Bonnie Prudden, a pioneer advocate for physical fitness. Contained within was a 24-page report on U.S. Fitness.

“Sports Illustrated in this issue presents the findings from a nationwide survey of activity and, in some cases, lack of it on behalf of physical fitness during the past two years,” wrote the magazine’s publisher H.H.S. Phillips Jr. “These are the years since President (Dwight D.) Eisenhower, alarmed by the results of the Kraus-Prudden study on fitness of our children, spotlighted the problem by means of a White House luncheon.”

Using a test devised by Austrian doctors Hans Kraus and Sonja Weber, the study found “that 56 percent of American children had failed at least one of a battery of fitness measures, including leg lifts and toe touches. By contrast, only 8 percent of European children had failed even one test component.” The presentation of the results led to the creation of the “President’s Council on Youth Fitness.”

“Ultimate solution must take the form of community and individual action,” continued Phillips in his “Memo from the Publisher.” “The series of weekly illustrated physical fitness lessons developed by Bonnie Prudden, which begins this week in Sports Illustrated, represent action which individuals may start taking at once.”

The Elk Lake Summer Palaestrum piece was part of the 24-page report. Charlie Pond felt that gymnastics were the base of every sport, and the article included an interesting sentence:

“Pond-trained pupils have passed the Kraus-Weber tests with ease.”

The Return of Gymnastics

The direct impact of the Summer Palaestrum and the establishment of the President’s Council on prep sports in Michigan is lost to time. But it is interesting to note that, after a 30-year absence, in May, 1960, the Michigan High School Athletic Association announced the reintroduction of a state gymnastics meet to its array of postseason activities. The first championships were scheduled for March 18, 1961, at Ionia High School.

Gymnastics for boys, and also in some places for girls, had taken hold at a sprinkling of schools around Michigan.

A fixture for men at state colleges and universities, as well as at the summer Olympics since their modern birth in 1896, the sport was among the original postseason activities sponsored by the MHSAA at its formation in late 1924 and 1925. However, during the early 1930s, high school athletics were under attack. Detroit city schools, led by health and physical education director Vaughn Blanchard, had initiated a self-imposed boycott of MHSAA postseason play following the 1929-30 school year to focus strictly on intracity play. In late March 1932, following a conference in Traverse City, the Michigan Education Association pushed for athletic reforms, stating they felt there was an over-emphasis on tournament competition among high schools of the state.

A fixture for men at state colleges and universities, as well as at the summer Olympics since their modern birth in 1896, the sport was among the original postseason activities sponsored by the MHSAA at its formation in late 1924 and 1925. However, during the early 1930s, high school athletics were under attack. Detroit city schools, led by health and physical education director Vaughn Blanchard, had initiated a self-imposed boycott of MHSAA postseason play following the 1929-30 school year to focus strictly on intracity play. In late March 1932, following a conference in Traverse City, the Michigan Education Association pushed for athletic reforms, stating they felt there was an over-emphasis on tournament competition among high schools of the state.

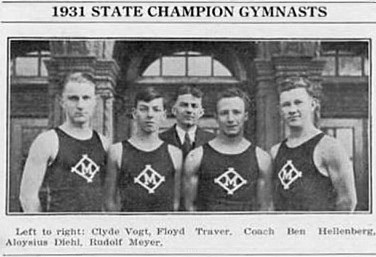

During the prior year, due to – among other things – the initial impact of the Great Depression, the MHSAA had made cuts and alterations to its programs. The annual state basketball tournaments were reorganized; separate tournaments were conducted for Upper and Lower peninsulas. Track & field saw the elimination of the javelin and discus events, while the annual gymnastics meet – won by Monroe in four of the seven years, including both 1930 and 1931 – was discontinued by the Association.

From 1932 until reinstatement, whatever statewide gymnastics competition occurred at the prep level happened under club, YMCA and Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) guidance.

Surprise Hotbed

Edwin Joseph Bengtson arrived at St. Clair as a new teacher in 1956. His brief biography in the Port Huron Times-Herald at the time of hire noted he came from Waltham, Mass. A former semi-professional baseball player, he would teach physical education.

In 1959, he started a gymnastics program at the school with nine students.

“The response has been terrific. Our kids are so enthused with gymnastics they go out and work on their own,” Bengtson told the Times-Herald following the 1960 season. “Last year we had only one medal winner. This season, we’ve already won 20 medals and 19 trophies and have high school and YMCA state champions.”

Junior Tom Hurt, the team’s top gymnast, earned the high school trampoline title, while freshman Jim Arnold won tumbling honors. The 1960 high school championships, hosted at Michigan State University’s Jenison Field House, was an AAU-sponsored event.

The St. Clair program included 36 students, both boys and girls, ranging from second graders to juniors in high school, and the coach expected to award at least seven varsity letters at season’s end.

He found little competition in the immediate area, and his teams competed against schools with much larger enrollments for the most part. Practices were three hours a day, six days a week. “We’ll give exhibitions any time. All you have to do is ask us. … We’ve even met at 4:30 a.m. for trips to various colleges in order to work out with their teams.

He found little competition in the immediate area, and his teams competed against schools with much larger enrollments for the most part. Practices were three hours a day, six days a week. “We’ll give exhibitions any time. All you have to do is ask us. … We’ve even met at 4:30 a.m. for trips to various colleges in order to work out with their teams.

“I also use a camera to take movies of the gymnasts in action. We later show the films and break down the various mechanics to help the performers improve. You could say we show films like football coaches do to find mistakes. Gymnastics depend on mechanics, courage and body discipline.”

So it really shouldn’t have come as a surprise when – led by Hurt – St. Clair, one of only two Class B-sized schools competing against 12 schools with Class A-sized enrollments, won the MHSAA’s 1961 Final competition. Or that the squad would repeat as champion in 1962 and 1963. Many of those St. Clair gymnasts would soon populate university squads: Hurt, with teammates Dennis Smith and Ron Aure, would each excel at Michigan State, while Arnold earned All-America honors at Eastern Michigan University. Arnold’s younger brother, Dave, first starred at Central Michigan before transferring to Michigan State.

Deadlocked with Ionia with two events remaining, a win by Aure in the long horse, and second, third and fifth-place finishes by Saints in all-around, gave Bengtson’s squad a 16-point win. Ionia ended in second, topping Alpena, the runner-up in 1961.

In the 1963 championship competition, the Saints topped Ann Arbor 144½-110½. Ionia finished third on the day. A total of 137 athletes from 15 schools competed. Ann Arbor’s Chris Vandenbrock ended the day as top all-around individual, but the next three were St. Clair’s Jim Arnold, Aure and Smith. Arnold captured four second-place finishes, a fourth, an eighth, and a tie for first in the still rings event. Aure finished with firsts in tumbling, vaulting, and the floor exercise.

According to the Hillsdale Daily Press, Tim Mousseau of Alpena, who as an eighth grader lost both legs when trying to hitch a ride on a slow moving New York Central train, was one of the sensations of the meet winning the parallel bars and finishing second in the still rings. (In college, Mousseau would compete for the University of Michigan.)

Over four seasons, Bengtson’s team won 70 of 84 dual or triangular meets, finishing second on eight occasions. In July 1963, the inevitable arrived. Bengtson was offered the opportunity at Auburn University, where he would work to establish and coach the women’s gymnastics program.

“I hate to leave St. Clair,” he said to the Times-Herald. “The people here have been awfully nice to me and my family, but this is a wonderful opportunity.”

Shake-up in Williamsburg, Move to MSU

While the gymnastics “Palaestrum” camp continued to operate under new leadership and instruction at Williamsburg, the “National Summer Gymnastics Clinic” moved to Michigan State University’s campus in 1961, run by MSU’s Szypula. The veteran coach had started the Spartans' men’s gymnastics team in 1947 and would retire in 1988. During an MSU career that spanned 41 years, he produced 48 individual Big Ten champions and 18 NCAA individual champions.

The three-pronged purpose of the six-day clinic, the school’s gymnastics coach told the Lansing State Journal, was “to develop better performance in gymnastics techniques, teaching, and officiating.” The 1962 gathering, as usual, featured a staff comprised of college coaches and past Olympian performers. Enrolled were nearly 150 boys and girls from 17 states and Canada. The MSU gymnastics coach said week-long elementary and secondary school level instruction were in “keeping with President (John F.) Kennedy’s emphasis on physical fitness.”

Bengtson was among the staff of 15 at the 1963 Clinic, and both Jim Arnold and Ron Aure were among the registrants. Arnold finished the week as the clinic’s top male high school senior performer.

By 1965, more than 200 young athletes from across the U.S. and Canada were on hand. Bengtson was again among the board and staff, now numbering 25.

“One of the highlights of the (1967) Clinic was the use of the new Ampex Videotape machine – one of the most modern machines available,” noted a post-clinic recap that appeared in Mademoiselle Gymnast,” one of the array of niche magazines that now focused specifically on the growing sport. “This machine was loaned to the Clinic by ‘Biggie’ Munn, Athletic Director at Michigan State University. We plan next year to use this machine more extensively.”

The location in East Lansing, at the center of the Lower Peninsula, certainly made the “National Summer Clinic” attractive to those interested in the sport. Around 300 were in attendance for the 12th annual Clinic at MSU in 1969. “We felt a clinic was needed,” Szypula told the Free Press. “Youngsters were not being taught fundamentals and advanced skills properly, and consequently physical educators need to learn techniques … of giving them a sense of security when they first begin gymnastics that require them to turn upside down.”

“During the six days of the clinic, both sexes try floor exercises, vaulting, tumbling and trampoline. The girls go on to the balance beam and uneven parallel bars, while boys acquire skill at even parallel bars, the horizontal bar, rings and side horse.”

Staffing for the 1969 clinic included, among others, three former members of Olympic teams: Jackie Klein Uphues, Ernestine Russell Carter, and Fred Orlofsky (who served as Western Michigan University coach from 1966 to 1996), as well as Clarenceville’s Thompson. The program continued to wrap with an extravagant “Night of Stars” performance.

Southeastern Michigan Leads the Way

Both Alpena and Ionia began their gymnastics program in 1955. Alpena excelled early, earning AAU high school titles in 1957 and 1959. In a write-up on the team in the school’s 1958 Anamakee yearbook, it was noted that female members of the squad were entered in an AAU state meet for the first time. By 1960, the school also sponsored a girls team.

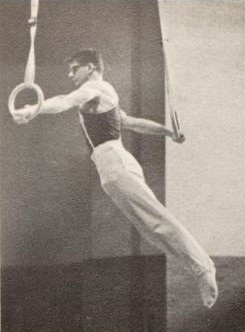

“State Champions! That’s our gymnastics team,” proudly shouted the 1964 Ionia yearbook as coach Vernon Vance led his 11-gymnast boys squad, featuring six seniors, to the title. Mike Husted earned first-place honors in the parallel bars and still rings and accumulated the most points on the day to claim the all-around medal. He would continue his gymnastics career at the University of Michigan.

The event featured 324 performances by 127 competitors from 11 schools. According to coverage in the Daily News, “to save time, there were three events going on all the time” for judges to evaluate.

Vance guided the Bulldogs to a second-place finish among a field of 18 schools and 125 gymnasts in 1965, finishing behind Ann Arbor, before accepting a teaching and coaching position at Lansing Waverly schools. Ionia, led by senior Joe Sawtell, again ended as runner-up in 1966, this time guided by coach Norman Brooks.

Coach Marv Johnson, who took over the gymnastics program at EMU in 1963, promoted and encouraged the growth of the sport in southeastern Michigan. Hosting annual all-state invitational meets, and training and providing judges, served as catalysts for the success of the sport in Lower Michigan according to Modern Gymnast magazine. The formation of the highly competitive Southeastern Michigan Interscholastic Gymnastics Association, established in 1966 by eight teams, was also credited with the strength of gymnastics programs from the area.

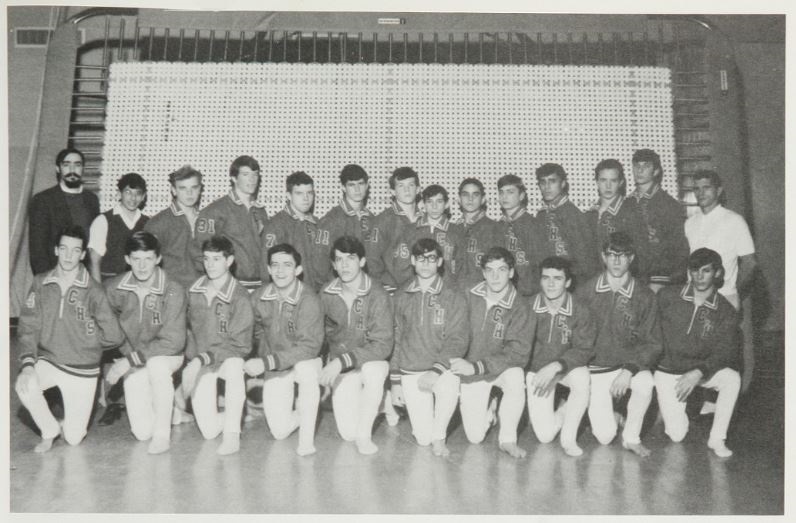

Runs to the state title by coach Richard Shilling’s teams at North Farmington (1966 and ’67) and by archrival Livonia Clarenceville (1968 and ’69), coached by Chuck Thompson and assisted by Ned Duke, illustrated the point.

Those two schools, less than eight miles apart, both entered the March 1968 MHSAA tournament with a single loss as they split their regular-season meets. In the Final, Clarenceville out-pointed the 1967 champion, 144½-139. Trojans senior co-captain Charles Morse won four events – horizontal bar, parallel bar, still rings and side horse and earned the all-around title. (As a junior in 1967, Morse had won four events).

According to the Plymouth Observer, the 5-foot-5, 140-pound Morse had been “handicapped during his younger days by a paralysis condition in his hips, his knees and ankles.” (Morse would later compete in three events at Michigan State, captain the Spartans and win the 1970 Big Ten title on the parallel bars.)

Jim McCannon, Clarenceville’s other captain, entered seven events, placed in all, and finished second in the all-around standings. Thirty schools had competed at the meet, hosted at Hillsdale High School.

Tom McArt of North Farmington won the free exercise while his teammates Terry Boys and John Peeples tied for top honors in the long horse.

“Thompson began the team five years ago with only a few participants,” noted the school’s yearbook, celebrating the championship. According to the Detroit Free Press. Thompson had graduated from Michigan State, where he had competed “as a trampoline and tumbling specialist and capped a Big Ten second place finish in 1960 with a third in the NCAA tournament.”

Duke, an eighth-grade science teacher at the junior high, was a former captain of the gymnastics team at the University of Michigan.

The Impressive Gymnasts of Taylor

Taylor Kennedy then rattled off four straight Finals championships spanning 1970-73 – just four years after starting a program. The program was guided by coach Roger Bechtol, with strong assistance by Joseph Sawtell. Bechtol had earned 11 varsity letters at Taylor Center High School, before playing four years of baseball at EMU. As a senior in 1962 at EMU, he also earned a letter on the school’s gymnastics team. Sawtell had won the 1966 MHSAA all-around as a student at Ionia before earning two varsity letters in the sport at Eastern.

Randy Mills grabbed the horizontal bar championship as a junior in 1970, grabbed parallel bars and all-around honors for Kennedy in 1971, and then followed his brother Lanny to compete at EMU. Mark O’Malley earned MHSAA titles in the floor exercise in both 1972 and 1973 before leading WMU’s gymnastic team to a pair of Lake Erie League titles.

Randy Mills grabbed the horizontal bar championship as a junior in 1970, grabbed parallel bars and all-around honors for Kennedy in 1971, and then followed his brother Lanny to compete at EMU. Mark O’Malley earned MHSAA titles in the floor exercise in both 1972 and 1973 before leading WMU’s gymnastic team to a pair of Lake Erie League titles.

Between 1970 and 1976, all three Taylor high schools - Kennedy, Truman and Taylor Center – would produce boys gymnastics champions.

“Coach Bechtol did something to inspire us. I can’t really describe it” said Tom Gonda, Jr., 50 years after winning the 1972 state pommel horse event for Kennedy at the meet hosted at Ann Arbor Pioneer. “His attitude was: supportive, curious, encouraging, positive. It wasn’t: dogmatic, fearful, intimidating or forceful.”

Bechtol would then lead Taylor Truman to the boys state gymnastics title in 1978. He coached gymnastics for 14 years, winning 10 league titles and, besides the five Finals championships, totaled two runner-up finishes in the sport. His teams posted a 189-32 record over the span. Bechtol was also an outstanding baseball coach at Kennedy then Truman, winning 492 games over 32 seasons.

Girls Sports Gain MHSAA Sponsorship

After long discussion at an Oct. 18, 1971 meeting, the MHSAA’s Girls Athletics Advisory Committee concluded that the Association should move forward with sponsorship of state meets in gymnastics, track & field, golf and tennis. At its December 1971 meeting, the MHSAA Representative Council, acknowledging the growing sponsorship of girls activities at member schools and the committee’s recommendation, decided to conduct a gymnastics championship during the 1971-72 school year. If all went well and schools desired, meets and tournaments in the other sports would begin during the following school year.

Three months later, in March 1972, Taylor Kennedy became the first school to earn the state’s girls gymnastics title. The team slipped past East Lansing by the slimmest of margins, 216.25-215, in a six-event match hosted at Hillsdale. A total of 275 gymnasts from 33 schools competed in the first girls championship. Merry Jo Hill of East Lansing (who would later compete at Arizona State) won the first all-around competition, placing first in the floor exercise, tying for first in tumbling, and finishing second in the balance beam and uneven parallel bars. Amy Balogh led Kennedy with wins on the balance beam, the uneven parallel bars and with a second in vaulting to finish second all-around.

Then the Kennedy girls, like the Kennedy boys, repeated as champions in 1972-73. (The same school year, the MHSAA sponsored its first Upper Peninsula girls gymnastics meet, won by Iron Mountain).

From 1972 through 1981, with the passage of Title IX, interest and participation in girls gymnastics soared across the nation. According to surveys, 52 girls teams competed in prep gymnastics in Michigan during the 1972-73 school year. For 1979-80, the number of girls teams had climbed to 140.

However, interest in boys gymnastics waned. During the 1972-73 school year, according to the MHSAA, Michigan had 27 boys teams. The total climbed to 34 in 1975-76. But by 1979-80, the total had fallen to 23. The next school year, the count was down to 18. The exact reason for the decline remains unknown.

Inflation during the late 1970s, followed by recession – the most severe since World War II – certainly impacted prep sports across Michigan as numerous school millage requests failed, impacting extracurricular activities including music programs across the state. Between 1979 and 1982, Michigan’s population dropped.

Gymnastics never was a revenue sport. Increased pressure to balance budgets, in addition to the growing number of athletic opportunities available for both boys and girls, quietly played a factor.

Last of the Champions

Ann Arbor High School, winner of the first boys gymnastics meet back in 1925, won the 1965 tournament. Renamed Pioneer High School in the fall of 1968 when the district’s new Huron High School opened its doors, Pioneer grabbed back-to-back titles in 1974 and 1975. (Dennis Rumbaugh, Newt Lokin, Jr. and Dorian Deaver each contributed first-place finishes, then later competed for U-M. Paul Hammonds did the same before joining the team at MSU.) The Pioneers earned a fourth and final title in 1979.

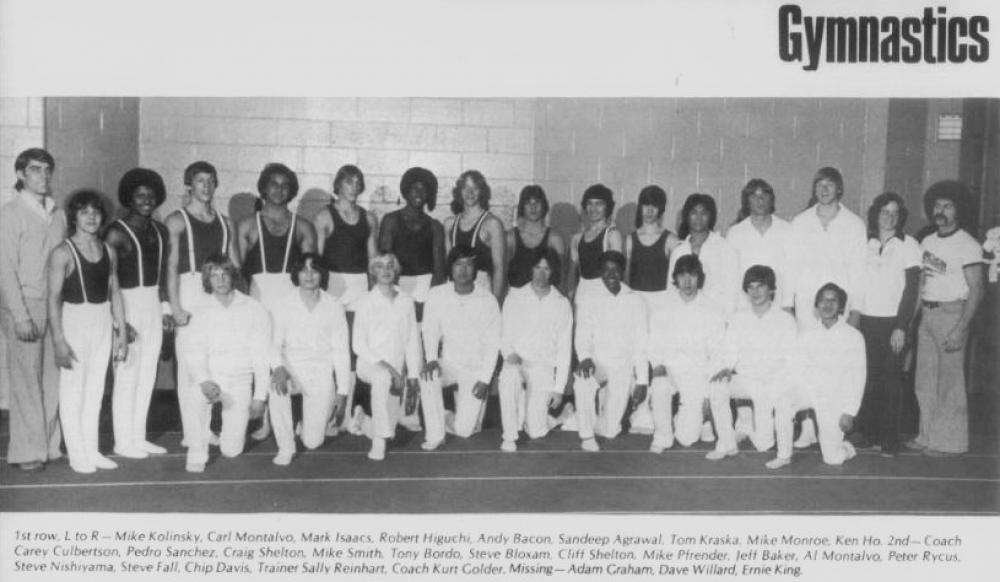

Huron won the 1978 boys title under head coaches Carey Culbertson and Kurt Golder. Golder, a 1972 Alpena graduate, was a three-time letter winner in gymnastics at Michigan. Later an assistant coach at Michigan State, then at Iowa, he was named head coach of the U-M men’s gymnastics team in July 1996, taking over following an 0-16 season. Only the fourth coach in the team’s more than 80-year history, his squads have won four of the school’s six national titles.

Alpena earned its first MHSAA boys gymnastics title in 1977, then grabbed consecutive championships in 1980 and 1981.

Longtime coach Jack Discher guided Alpena to that first crown.

“What made the championship even sweeter,” noted the Alpena News years later, “was the Wildcats won it on their home floor in front of one of the largest crowds ever for a state final.”

Discher had come to Alpena from North Dakota, taking charge in 1967. With his assistants, he turned out strong teams and stellar athletes including among others Roger Tolzdorf, Howard Welsh, Lynn Cousineau, Scott McKenzie, Ken Donakowski, Tom Nadeau, Golder and his brother Cory.

He went back to North Dakota after that school year to coach girls gymnastics at Fargo North. His assistant, Ray Timm, an Alpena graduate and another former gymnast at U-M, took the Wildcats to their back-to-back titles.

The 1981 championship would be the last for the boys sponsored by the MHSAA. At a May 1981 meeting, ironically held in Alpena, the MHSAA Representative Council took up the topic of boys gymnastics.

“Four School teams and individuals from a maximum of ten schools participated in the 1981 Final Boys Gymnastics Meet,” noted the Council in the minutes of the meeting, published in the MHSAA’s monthly bulletin. “After considerable discussion of Handbook Regulation 11 Section 1, Interpretation #69, it was determined that the MHSAA should not sponsor a Final Boys Gymnastics Meet for the 1981-82 school year. It was with reluctance that the Council made the decision but it felt that the Final Tournament should not be continued when only ten schools in the state sponsor boys gymnastics.”

A decade later, eight high schools in Michigan, including ionia, Ann Arbor Pioneer, and Ann Arbor Huron, still sponsored boys gymnastics programs during the 1990-91 school year. Among the boys coaches was George Szypula at East Lansing. The count continued to dwindle. By 2005, there were none.

Tumbling Forward

In 1976, owner and director of the “Palaestrum” Ruth Ann McBride told the Free Press that the 1972 Olympic Games, which featured the Soviet Union’s Olga Korbut, “set off a gymnastics boom in America,” especially among girls. Two-thirds of her campers, ranging in age from 9 to 18, were female. Romania’s Nadia Comăneci was expected to do the same in 1976.

McBride was a former gymnast, attendee and/or coach at Williamsburg and Michigan State. Her father Francis Inskip had been one of the original investors in the Pond’s Palaestrum. She had been associated with the Williamsburg Elk Lake site since 1962 and had been the camp’s director since 1966.

While the popularity of the sport among girls has since declined, especially since the sponsorship of competitive cheer championships by the MHSAA began in 1994, the girls tournament lived on. Following the 2002-03 school year, the Upper and Lower Peninsula tournaments consolidated into one.

Statistically, while nothing exists to connect the early popularity of the sport to the “National Summer Gymnastics Clinic” or the Williamsburg “Palaestrum,” it certainly seems logical that the annual events had impact.

A survey by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) showed 1,097 high schools in 36 states sponsored boys gymnastics programs during the 1979-80 school year. Now, only 104 high schools in seven states still have boys gymnastics programs. In total, there are only 1,580 participants. Of those 104 schools, 52 are in Illinois. Fewer and fewer colleges and universities sponsor men’s teams. Today, the sport – at least for most males – is mostly taught in gymnastics clubs and junior Olympics.

Gonda, who went on to become a highly-respected and successful thoracic surgeon, reflected on the changes.

“We’ve lost something with the demise of high school gymnastics,” he said. “Many times, the men in gymnastics didn’t always find another talent for other sports.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

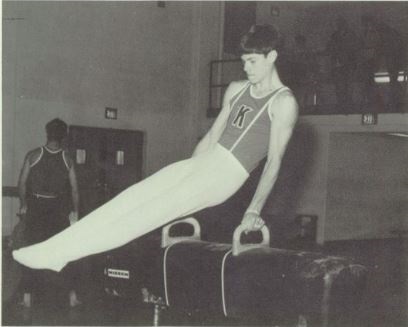

PHOTOS: (Top) Ed Bengtson and his St. Clair team won the 1961 championship after boys gymnastics rejoined the list of MHSAA-sponsored tournament sports. (2) Monroe won the last of the first wave of MHSAA boys gymnastics championships in 1931. (3) Winner of three events at the MHSAA Final, Michael Husted helped lead Ionia to the 1964 title. (4) The 1968 Livonia Clarenceville team won the first of two straight titles. (5) Tom Gonda Jr. won the 1972 state pommel horse event for Taylor Kennedy. (6) Ann Arbor Huron’s 1978 champions were coached by a pair of former University of Michigan gymnasts, Carey Culbertson and Kurt Golder. Golder, a 1972 Alpena graduate, today serves as U-M’s men’s gymnastics coach. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch.)