Century of School Sports: Why Does the MHSAA Have These Rules?

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

September 18, 2024

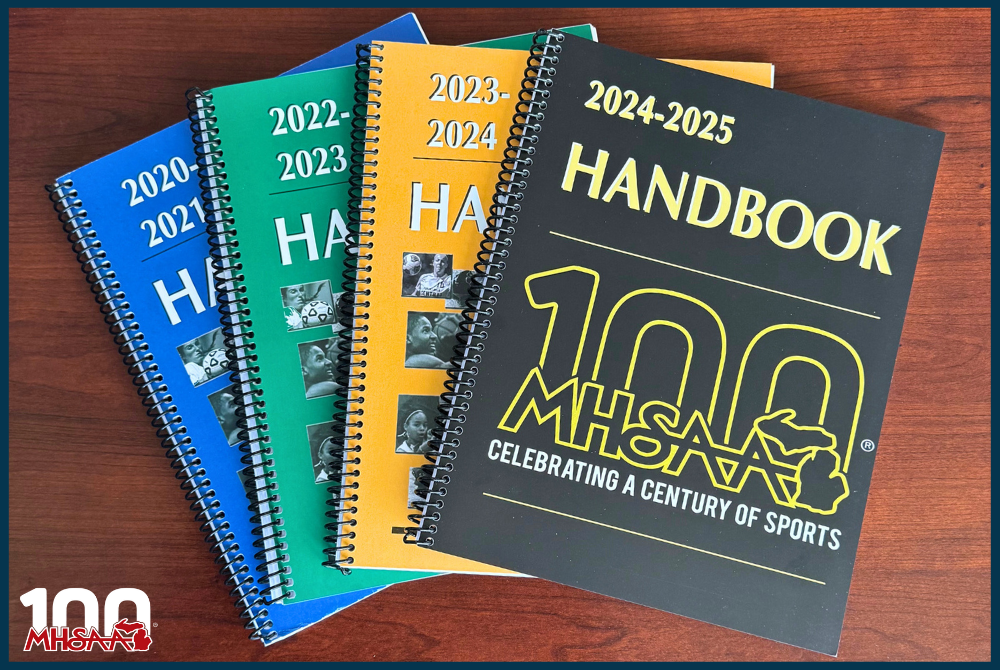

MHSAA administrators are two trips into their annual seven-stop fall tour that has become a tradition during nearly half of the Association’s “Century of School Sports” – and this year, a focus has been on answering a key question at the heart of educational athletics since long before the MHSAA was formed during the 1924-25 school year.

The MHSAA’s Update meeting series is in its 47th year and includes half-day conferences in seven locations – generally in the Kalamazoo, Metro Detroit, Grand Rapids, Saginaw, northern Lower Peninsula and mid-Michigan areas, and at Northern Michigan University in Marquette. The six Lower Peninsula sessions begin with an athletic director in-service during which MHSAA assistant directors explain recent rules changes and discuss challenges our administrators face on a daily basis (with Upper Peninsula athletic directors participating in a similar in-service during the spring).

Those in-services are followed by a session with executive director Mark Uyl, who speaks to athletic directors, superintendents, principals and school board members on a variety of topics including the MHSAA’s current objectives and ideas for the future, while also reinforcing the longstanding values that remain the bedrock of our daily work.

And that leads to the question he’s presenting across the state this fall:

Why does the MHSAA have these rules?

Frankly, the answer goes back to the beginning of school sports in Michigan – all the way back to 1895, when the first MHSAA predecessor organization was formed.

The first MHSAA Representative Council president Lewis L. Forsythe explained in his book “Athletics in Michigan High Schools – The First Hundred Years” how regulations always have been necessary:

“Eligibility rules are a necessity in interscholastic competition. It was common acknowledgement of this fact that led to the first State inter-school organization in 1895. The rules at first were few, simple and liberal. But with the passing of the years they came to be more numerous, more complex, and more restrictive, again through common acknowledgment of desirability if not of necessity.”

That necessity – and the reasoning behind it – has not changed.

Two main points explain why rules are absolutely imperative for educational athletics to thrive.

► 1. Participation – through providing as many opportunities as possible for students to play – has been the mission of school sports since their start. Rules contribute to the value of participation.

If there are requirements for children to participate in athletics – for example, an academic standard or rules that dissuade students from switching schools every year – then school sports programs mean more to all involved.

If we raise the bar, raise the standards of eligibility and conduct, we raise the value of our school sports programs. If we lower the bar, we lower the value of being part of school sports – because without rules, contest results are meaningless, and the value of participating is diminished.

► 2. We have rules where the stakes are higher, and agreement is lower – because where the stakes are highest, there is the greatest tendency for some people to try to gain an unfair advantage, and the greatest need for rules to curb possible dishonest activity.

This statement goes to the heart of the history, rationale and application of MHSAA rules. Obviously and simply put, school sports mean a lot to those who take part, and that significance is high enough to stoke disagreement – and we need rules to govern those disagreements. We have the most rules for high school sports, where championships are at stake and the possibility of disagreement is greatest.

***

Finally – and perhaps providing the strongest reinforcement of the two points above – is this:

Schools choose to make MHSAA rules their own.

Quite literally, school districts vote annually to be part of the MHSAA – and confirming this voluntary membership comes with the requirement to follow all MHSAA rules.

When schools challenge our rules, they literally are seeking to break the rules they already have committed to uphold.

These rules, and this commitment, are the strength of our organization across 752 member high schools and several hundred more middle schools and junior high schools. They have been constructed on a century of precedents and after considerations by representatives of those same member schools – representatives those schools have voted to elect every school year during the MHSAA’s history.

Previous "Century of School Sports" Spotlights

Sept. 10: Special Medals, Patches to Commemorate Special Year - Read

Sept. 4: Fall to Finish with 50th Football Championships - Read

Aug. 28: Let the Celebration Begin - Read

NFHS Voice: 'Commit' is Verb, not Noun

January 13, 2020

By Karissa Niehoff

NFHS Executive Director

When is “commit” not a verb? According to Webster’s never – that is, unless the reference is to where the high school’s star quarterback is headed to college.

Even in game stories, the “top” players on high school teams are often referred to as a “(name of college) commit.” It seems innocent enough, but the continual focus on a player’s advancement to the next level is concerning given the current – and future – landscape of college sports.

With the NCAA’s recent decision to allow athletes to earn compensation for their name, image and likeness, high school sports governed by the NFHS and its member state associations will be the last bastion of pure amateur competition in the nation. And it must remain that way.

The focus on the individual rather than the team that often grabs the headlines in college basketball and football cannot become a part of high school sports. In college basketball, there is constant discussion about who the “one and done” players will be. At the end of the season in college football, the talk is about which juniors are turning pro and which players are sitting out bowl games to guard against injury.

Although we recognize that this decision by the NCAA was perhaps inevitable as a result of the earlier “Fair Pay to Play Act” by California Governor Gavin Newsom, we are concerned that it will further erode the concept of amateurism in the United States.

While only about one percent of high school boys basketball players and about 2.8 percent of high school 11-player football players will play at the NCAA Division I level, the perks offered to attend certain colleges will be enhanced and recruiting battles could escalate. Current issues with parents pushing their kids into specialization in the fight for scholarships could intensify as they consider the “best offer” from colleges.

This weakening of the amateur concept at the college level must not affect the team-based concept in education-based high school sports. The age-old plan of colleges relying on high schools for their players will continue; however, high school coaches and administrators must guard against an individual’s pursuit of a college scholarship overriding the team’s goals.

As the new model develops at the college level, the education-based nature of high school sports must be preserved. These programs cannot become a training ground or feeder program for college sports.

Instead, the focus should be on the millions of high school student-athletes who commit (an action verb) to being a part of a team and gain untold benefits throughout their high school days. Some of these individuals will play sports at the college level and move on to their chosen careers; others will take those values of teamwork, discipline and self-confidence from the playing field directly into their future careers.

There is nothing more sacred and fundamental to the past – and future – history of high school sports in the United States than the concept of amateurism. It is up to the NFHS and its member state associations to ensure that education remains the tenet of high school sports.

Dr. Karissa L. Niehoff is in her second year as executive director of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) in Indianapolis, Indiana. She is the first female to head the national leadership organization for high school athletics and performing arts activities and the sixth full-time executive director of the NFHS, which celebrated its 100th year of service during the 2018-19 school year. She previously was executive director of the Connecticut Association of Schools-Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference for seven years.