Official Loved Giving Back to Community

By

Doug Donnelly

Special for MHSAA.com

November 10, 2020

MORENCI – Before referee Jerry Hoffman died that Friday night, he knew the two football teams were going to gather in the center of the football field to pray for him.

“They were starting to take him off the field and I went to him and told him that we were going to circle up and pray for him,” Sand Creek football coach Scott Gallagher said. “He said, ‘Thank you Scott. I appreciate your faith.’”

A short time later, while he was being readied to be transported from ProMedica Charles and Virginia Hickman Hospital in Adrian to Toledo Hospital, Hoffman, 78, died. A football referee for decades, Hoffman’s last assignment ended up being the Oct. 30 Sand Creek-Pittsford playoff game.

During the game Hoffman, who was one of the line judges, dropped to a knee and collapsed. At times he was unconscious on the field. Medical personnel raced onto the field to assist him. At one point he said he wanted to sit up, but quickly went back to the ground.

“They responded immediately,” said Sand Creek athletic director Robert Wright, who has known Hoffman for more than 35 years. “They were right there with him. When I got to him, I was able to tell him that I would call Dan (his son). There was this calmness through it all because we had the right people there to take care of it.”

His son, a longtime area educator, football coach and track coach, Dan Hoffman, said he and his family were touched by how the players, coaches and fans from the two schools came together.

“What a blessing we have in these small schools,” said Dan Hoffman. “I don’t think they could have responded in a better way.”

Jerry Hoffman was a native of Wauseon, Ohio. He and his wife, Mary Ann, moved to Morenci in 1966. He worked at a variety of jobs, from a chemical company in Weston to being self-employed for a long time. While not working, he did things like garden. One of his passions was being involved in sports as an umpire and referee.

Jerry Hoffman was a native of Wauseon, Ohio. He and his wife, Mary Ann, moved to Morenci in 1966. He worked at a variety of jobs, from a chemical company in Weston to being self-employed for a long time. While not working, he did things like garden. One of his passions was being involved in sports as an umpire and referee.

“He had probably been to Sand Creek hundreds of times to referee a football game or baseball game or basketball,” Wright said. “His heart was always with kids. He was a great guy – always had a smile on his face.”

Dan Hoffman said his dad was a referee when he was young, then stepped away from it when he and his siblings were in high school to watch them participate in sports. He picked it back up a few years ago and was not really thinking about getting out of it despite being 78 years old.

“He was a hard worker,” Dan said. “He taught us that. He loved many things, but being a referee was one of them. We would talk about him retiring, and he said he wanted to referee football until he was 80. This year he thought he was going to cut back on basketball, but then his schedule started filling up.

“He loved being out there, out with the kids and giving back.”

Always a devout Christian, Hoffman became a substitute pastor at Canandaigua Community Church in recent years, then interim pastor and finally, pastor.

“He kept living, that’s for sure,” Dan Hoffman said. “He always wanted to push things. Everything he did, he did to extreme. He taught us a lot."

Kay Johnson, a former Morenci athletic director and softball coach for more than 40 years, said she welcomed seeing Hoffman come to Morenci to referee a sporting event.

“He really loved doing it,” she said. “He was there for the right reasons, the kids. He was always really kind. He’d arrive early and always talk with the kids.”

Jerry and Mary Ann had seven children, 16 grandchildren and 12 great-grandchildren. They were foster parents to more than 20 children over the years.

“He rubbed a lot of elbows with a lot of people, especially in Morenci,” Dan said. “He volunteered a lot, served on some boards. He definitely made an impact on his community.”

Sand Creek and Pittsford were in the middle of their playoff game on Ernie Ayers Field at Sand Creek when Hoffman collapsed. Gallagher and Pittsford head coach Mike Burger met and decided to circle the players up. The photo has been widely circulated on social media the last couple of days.

One of Sand Creek’s captains, Jackson Marsh, helped organize the prayer and spoke to the two teams.

“I saw the referees blowing the whistle and stopping the play,” said Marsh, a senior. “Someone said they saw him grab his heart. When I heard that I was like ‘Oh, no. That is not good.’”

Marsh said the two teams went to their respective sidelines and he and a teammate began praying. When the teams came together on the field, he led the prayer.

“I just prayed the Lord be with him and watch over his family,” Marsh said. “You hear about things like that, but you never expect to go through it. For me, it did not really click until after the game and we were walking off. That’s when it hit me what had happened.”

Hoffman said he saw the photo on social media late Friday, and it brought tears to his eyes.

“My dad loved great displays of sportsmanship, and I’m sure he would have loved to see that,” Dan Hoffman said. “When I saw the picture of the two teams circling up, I just thought it was an unbelievable display of compassion. Our family was touched by that.”

PHOTO: (Top) The Sand Creek and Pittsford football teams meet at midfield to pray for official Jerry Hoffman. (Top photo courtesy of Red Letter Productions/Sand Creek High School. Head shot from obituary posted by Anderson Funeral Home.)

Friday Nights Always Memorable as Record-Setter Essenburg Begins 52nd Year as Official

By

Steve Vedder

Special for MHSAA.com

August 31, 2023

GRAND RAPIDS – All Tom Essenburg could think of was the warmth of a waiting bus.

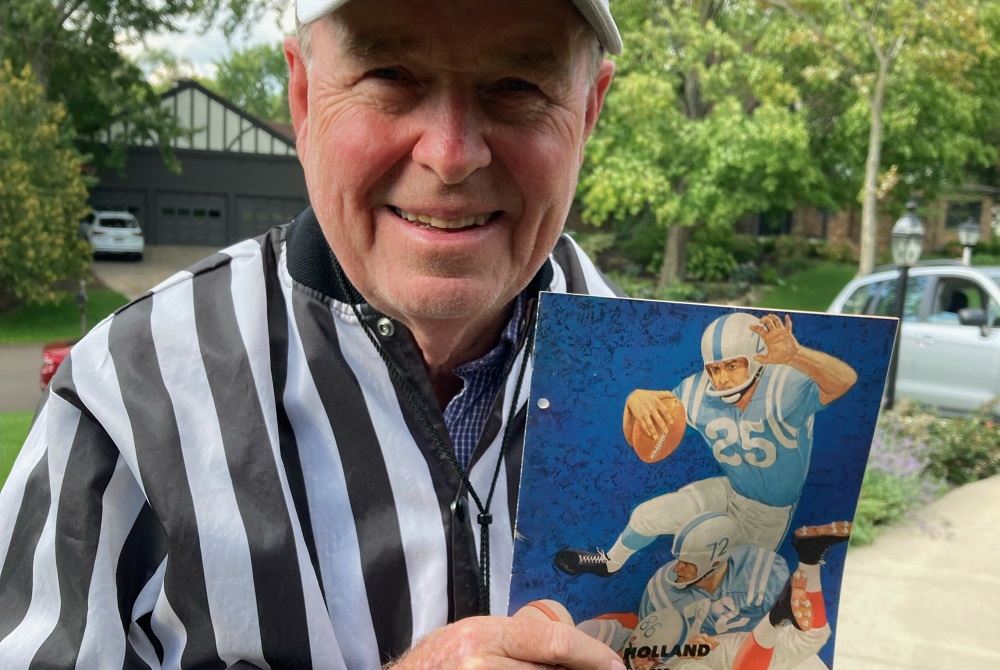

Five decades later, that's what Essenburg – then a senior defensive back at Holland High School – remembers most about a stormy Friday night before 2,100 thoroughly drenched fans at Riverview Park. He recalls having a solid night from his position in the Dutch secondary. He remembers a fourth-quarter downpour, Holland eventually winning the game and trudging wearily through the lakes of mud to the team's bus.

But what never dawned on Essenburg until much later was that he had been the first to accomplish something only three defenders in the history of Michigan high school football have ever done:

Intercept five passes in a single game.

"I knew after the game that I had a bunch of them, but (at the time) we were in a 0-0 game and my mind was on just don't get beat (on a pass) and we lose 7-0," he said of the Sept. 21, 1962, contest against Muskegon Heights.

It wasn't until the next morning's story in the Holland Evening Sentinel that Essenburg grasped what exactly had happened. He didn't realize until then that he had picked off five passes in all, including two over the last 1:52 that sealed a 12-0 win over Muskegon Heights. One of the interceptions went for a 37-yard touchdown, which Essenburg does vividly remember.

"I remember thinking to myself that I had to score," said Essenburg, who has been involved with high school sports in one fashion or another for more than 60 years. "There was a Muskegon Heights guy who had the angle on me and I pretty much thought I was going to get tackled, but I got in there."

Essenburg's recollection of the first three interceptions is a bit hazy after 61 years, but the next day's newspaper account pointed out one amazing fact. The Muskegon Heights quarterback had only attempted six passes during the entire game, with five of them winding up in the hands of the 5-foot-8, 155-pound Essenburg – who had never intercepted a single pass before that night. He would later intercept two more in the season finale against Grand Rapids Central.

It wasn't until the middle 1970s that Essenburg began wondering where the five-interception performance ranked among Michigan High School Athletic Association records. What he remembers most about the game was the overwhelming desire to find warmth and dry out.

"I just wanted to get to the bus and get warm. We were all soaked," he said. "For me it was like, 'OK, game over.' I was just part of the story."

Curiosity, however, eventually got the better of Essenburg. A decade later he contacted legendary MHSAA historian Dick Kishpaugh, who in an attempt to confirm the five interceptions, wrote to Muskegon Heights coach Okie Johnson, who quickly verified the mark.

It turns out that at the time in 1962, nobody had even intercepted four passes in a game. And since Essenburg's record night, only Tony Gill of Temperance Bedford on Oct. 13, 1990, and then Zach Brigham of Concord on Oct. 15, 2010, have matched intercepting five passes in one game.

Three years after Essenburg's special night, Dave Slaggert of Saginaw St. Peter & Paul became the first of 17 players to intercept four passes in a game.

Essenburg laughs about it now, but his five interceptions didn't even earn him Player of the Week honors from the local Holland Optimist Club. Instead, the club inexplicably gave the honor to a defensive lineman.

Essenburg laughs about it now, but his five interceptions didn't even earn him Player of the Week honors from the local Holland Optimist Club. Instead, the club inexplicably gave the honor to a defensive lineman.

It was that last interception Essenburg cherishes the most. His fourth with 1:52 remaining at the Holland 17-yard line had set up a seven-play, 83-yard drive that snapped a scoreless tie. Then on Muskegon Height's next possession, Essenburg grabbed an errant pass and raced 37 yards down the sideline to seal the game with 13 seconds left.

In those days, running games dominated high school football and defensive backs were left virtually on their own, Essenburg said.

"I kept thinking don't let them beat you, don't let them beat you. No one can get beyond you. In those days, once a receiver got in the secondary, they were gone," said Essenburg, who describes himself as a capable defender but no star.

"I wasn't great, but I guess I was pretty good for those days," he said. "I'm proud that I'm in the record book with a verified record."

Essenburg's Holland High School career, which also included varsity letters in tennis and baseball, is part of a lifelong association with prep sports. After playing tennis at Western Michigan, he became Allegan High School's athletic director in 1971 while coaching the tennis team and junior varsity football from 1967-73.

But he's most proud of being a member of the West Michigan Officials Association for the last 47 years. During that time, Essenburg estimates he's officiated more than 400 varsity football games and nearly 1,000 freshman and junior varsity contests. In all, he's worked 83 playoff games, including six MHSAA Finals, the most recent in 2020 at Ford Field. An MHSAA-registered official for 52 years total, he's also officiated high school softball since 1989.

Essenburg also worked collegiately in the Division III Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association and NAIA for 35 years, including officiating the 2005 Alonzo Stag Bowl.

Essenburg said the one thing that's kept him active in officiating is being a small part of the tight community and family bonds that make fall Friday nights special.

"I enjoy being part of high schools' Friday night environment," he said. "All that is so good to me, especially the playoffs. It's the small schools and being part of community. I used to say it was the smell of the grass, but now, of course, it's turf.

"I can't play anymore, but I can play a part in high school football in keeping the rules and being fair to both teams. That's what I want to be part of."

While it can be argued high school football now is a far cry from Essenburg's era, he believes his even-tempered attitude serves him well as an official. It's also the first advice he would pass along to young officials.

"My makeup is that I don't get rattled," he said. "Sure, I hear things, but does it rattle me? No. I look at it as part of the game. My goal is to be respected.

"I've never once ejected a coach. It's pretty much just trying to be cool and collected in talking to coaches. It's like, 'OK Coach, You've had your say, let's go on."

While Essenburg is rightly proud of his five-interception record, he believes the new days of quarterbacks throwing two dozen times in a game will eventually lead to his mark falling by the wayside. And that's fine, he said.

"It'll get beaten, no question. It's just a matter of when," he said. "Quarterbacks are so big now, like 6-4, 200 pounds, and they are strong-armed because of weight programs. They throw lots of passes now, so there's no doubt it's going to happen."

Until Essenburg is erased from the record book, he'll take his satisfaction from his connection with Friday Night Lights.

"I love high school sports and being with coaches and players," he said. "My goal was once to work for the FBI or be a high school coach, but now I want to continue working football games on Friday nights until someone says no more."

PHOTOS (Top) Tom Essenburg holds up a copy of the program from the 1962 game during which he intercepted a record five passes for Holland against Muskegon Heights. (Middle) Essenburg, left, and Al Noles officiate an Addix all-star game in Grand Rapids. (Photos courtesy of Tom Essenburg.)