‘Tis (out of) the Season

April 2, 2015

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

Those who live in close proximity to high schools throughout Michigan don’t even need a calendar to know what time of year it is when a new sports season begins.

Whistles piercing through the hum of their air conditioners on the first Monday morning in August mark the start of fall from nearby football facilities. The ping of aluminum as sidewalks and grass re-appear from winter’s grip signifies the start of spring.

Office supply stores could see calendar sales soar in those households – or occupants might at least do a double-take when checking smartphone calendars – in the near future if MHSAA out-of-season coaching regulations are modified. The familiar sounds of the seasons could resonate in non-traditional months as well.

A major topic of the recent MHSAA Update Meetings and AD In-Services in the fall was the possibility of revamping the regulations regarding out-of-season contact for school coaches with school teams during the school year. The Summer Dead Period would remain in place and has been largely supported by membership since it was implemented for the 2007-08 school year.

It should be noted that out-of-season revision is not a certainty, but simply in the exploratory stage at this point.

Yet, the time was ripe to initiate discussion on this topic in the fall. The growth of non-school athletic programs and demands placed upon students by such entities in recent years was one factor. The difficulty the MHSAA has enforcing – and schools have interpreting – current out-of-season coaching regulations is another factor.

“The fundamental question is how to allow more contact between coaches and students out of season without encouraging single-sport participation,” MHSAA Executive Director Jack Roberts said.

Can this be done? Can trends toward specialization and away from multi-sport participation be reversed through greater contact periods for each sport within the school year?

Proponents of this school of thought believe that time otherwise spent with non-school coaches would be best served with education-based coaches who, in theory, would be on the same page with peers at their school, all encouraging multi-sport participation.

“Part of the explosion of AAU and club involvement has been the perpetuation of the notion that without additional training and competition, students will not reach their potential nor maximize their chances of being recruited by colleges,” said Scott Robertson, athletic director at Grand Haven. “When our high school coaches have the ability to provide a similar experience, but with an education-first mindset regulated by athletic directors, the expectations of student-athletes by coaches can be tempered.”

It is a lively debate that will be picking up momentum for the remainder of this school year and into the next.

Following are some of the concepts and comments from the fall, with key points from a statewide survey to be published later this week. The MHSAA's Representative Council discussed these results at its March meeting, and action is possible during its final meeting of the school year in May.

Let's begin

Perhaps the most criticized, misinterpreted, ignored, and/or difficult to enforce rule in the MHSAA Handbook resides in Regulation II, Section 11 (H): the three- and four-player rule for coaches out of season during the school year. (See bottom of this page.)

Debate has long spiraled in dizzying circles around definitions such as “open gyms,” “under one roof,” “conditioning,” “drills,” and other components.

“One of the problems is the MHSAA finds this specific rule difficult to enforce and interpret,” MHSAA Associate Director Tom Rashid said. “Another perceived problem is that there might be a disconnect between school coaches and students out of season, which might be driving students toward non-school programs.”

It’s simple to recognize lightning rods, but quite another to construct a device for harvesting the sparks in a productive manner. To that end, Rashid prepared an outline for discussion on the topic as he hit the trails around Michigan this fall for Update Meetings and AD In-Services.

“We felt we needed to see if we could do better,” Rashid said. “Rather than say to 600 ADs, ‘What do you think about out-of-season coaching rules?’ we asked about a new concept. We created a starting point for discussion.”

The basic premise brought forward to the masses was this: a voluntary contact period of one month to six weeks with a limit of 10 or 15 days of contact in that period – and perhaps three in any one week – between a coach and his/her athletes out of season with any number of students, grade 7-12. Due to large participation numbers in football, some consideration was given to limiting the number of players in any one out-of-season session to 11, thus not creating “spring football.”

A straw poll from the gatherings in the fall indicated nearly 70 percent of attendees in favor of “contact periods” versus the current rule, prompting a detailed survey to all member schools sent in October to further measure the climate and hone in on specifics for desired changes.

“It was a very open process with great discussion,” Rashid said. “All size schools, all demographics, and all corners of the state weighed in.”

As always, the devil is in the detail, and the October survey yielded plenty of detail.

Numbers favor no numbers

As mentioned earlier, nearly 70 percent of attendees at MHSAA fall gatherings indicated that they might prefer a rule that specified coaching contact periods outside their sport during the school year, as opposed to limiting the number of student-athletes per session.

The ensuing survey sent to member schools in late October reflects that sentiment in schools of all sizes, and in all zones of the state. On the topic of counting contact days out of season with no limit on the number of students involved, more than 72 percent of 514 responding schools favored the plan. Class A schools led the way with nearly 76 percent in support. Class D schools chimed in at 69 percent in favor. Support was strong across the zones of the state as well, led by the Detroit metro area (Zone 3) at 76.5. The middle of the state (Zone 5) was the low, but still found close to 60 percent in favor of such a revision.

The survey revealed consistencies across the board relative to the amount of three- and four-player sessions currently utilized by schools of different sizes, and the support and opposition to questions regarding revised regulations on the topic. For instance, nearly 50 percent of Class A schools indicate that their coaches work with students under the current rule most every week during the offseason, while 40 percent of Class D schools report that most of their coaches never utilize the three- or four-player rule at all out of season. Not surprisingly then, in questions posed where three-and four-player stipulations might still exist, the larger schools favored such changes at a higher rate than the smaller schools.

Survey data also reveals a reason for such opposition at lower-enrollment schools: a simple numbers game. In Class C and D, the majority of schools report that 60-80 percent of their student-athletes participate in more than one sport. So, with more students busier year-round than at their larger school counterparts, there are fewer people to attend out-of-season sessions.

Similarly, the concept of extending the current preseason down time for all sports was supported more in Class C and D schools than Class A and B.

“It is always a challenge for individual schools to see things from the other schools’ perspectives,” Rashid said. “It’s hard for people to say, ‘It might be different for us, but for the greater good, we might have to change our culture here.’”

But, that line of thinking is certainly understood at Chelsea High School, a Class B school of more than 800 students. Athletic director and football coach Brad Bush is an advocate of multi-sport participation, regardless of school size.

“The current three- or four-player rule benefits kids by developing skills, but does not force kids to feel pressure to be at a full practice,” Bush said. “Changing this rule could reduce the number of multiple-sport athletes. Our staff and league is united in believing that changing this rule could be a big mistake.”

Outside influence

Part of the balancing act in attempting to revise out-of-season rules is to encourage greater participation on school teams, while not promoting specialization.

Interestingly, a number of schools in the survey reported that they have policies in place limiting in-season athletes from attending sports-specific training from out-of-season coaches. The percentages ranged from 27.6 percent in Class D to 41 percent in Class B.

Most schools allow weightlifting during the season, followed in decreasing order by three- or four- player workouts, conditioning and open gyms. However, more than 40 percent of responding schools have in place a policy prohibiting non-school competition for in-season athletes. The message seems to be that if activity is taking place, the preference is for it to be under supervision, and for that supervision to come from school coaches.

“If a coach is going to hold three workouts per week out of season, a student may leave another sport to play in the offseason of their preferred sport,” Rashid said. “As such, many ADs identified that it would be the role of each school to regulate out-of-season coaching. Right now, the ADs have to keep a handle on out-of-season activities and if the rules change, depending on their demographic, they might need to be involved even more.”

With advance planning, an environment can be created in which all of a school’s sports can exist in harmony and encourage multi-sport membership.

“Athletic directors can guide all coaches on their staffs to work together to create 12-month calendars that focus on the needs of kids and respect the desire of many to participate in multiple sports,” Robertson said. “In doing so, coaches can work to avoid overlaps in important opportunities where kids may be put in win-lose situations. With careful planning student-athletes will be afforded more opportunities to train and develop with their classmate peers and within their own communities.”

Chris Ervin, athletic director at St. Johns High School, is one of many in the camp that believes the current system accomplishes a school’s missions when properly supervised.

“Our coaches have ample opportunities to coach in the three- or four-player setting, and our athletes have plenty of opportunities to improve their skill sets through open gyms which are not coach-directed,” Ervin said.

Others agree that any change might introduce unwanted consequences. One source, an administrator in a strong football community, speculates in that town and others like it, football programs could smother other sport programs by scheduling full workouts on top of other in-season sports. Voluntary or not, it is opined that kids would gravitate toward the out-of-season football workouts if that’s the signature sport in town.

Ervin can see the same point. “I don't see this affecting my role too much, but I do believe this could lead to even more specialization. For example, if football coaches are able to work with their players 11 at a time in the offseason, I believe athletes will feel more pressure to be part of that football workout while they are in-season with another sport.”

Under another scenario, school coaches might someday be allowed to coach non-school teams during the school year. The rationale is that if students are participating outside the school campus anyway, wouldn’t it be better that they are coached by school personnel so that the educational message is delivered appropriately?

Add to this the fact that 100 percent of surveyed schools reported conducting open gyms in basketball and 66 percent in volleyball – the two most high-profile AAU sports – would it benefit schools to have trained personnel in those non-school leadership roles?

“This would connect our coaches to school kids but also could have the unintended consequence of specialization,” Rashid said. “However, the coaches in place would be our coaches, whereas currently we don’t have a say in the AAU coaches of our students.”

Not yet. This topic on the survey was favored by roughly 60 percent overall, but an equal 20.4 percent were at opposite ends of the spectrum strongly in favor and strongly against, with the highest percentage falling just above lukewarm.

By Class, the C and D schools were slightly more opposed to this idea than Class A and B. Why? Very often, in the smaller communities, there are no non-school opportunities; school sports are the only option.

Robertson believes that incorporating a revised out-of-season coaching plan could assist families financially in the long run.

“By having the ability to include larger numbers of kids in development activities and allowing for a limited number of competitions, there is a strong likelihood that students and their families will choose the out-of-season activities offered by their schools over the AAU/club activities that exist,” Robertson said. “In doing so, there will be no rental of outside gyms, no mandatory club fees, and reduced costs to families.”

Not all ideas have elicited opposing views. One item on the docket that schools uniformly opposed was the possibility of scrimmages within the out-of-season contact period. Most schools indicate a preference for these periods to be instructional only.

Just a tweak

Perhaps the current rule just needs a splint and not a full cast. Maybe it’s not broken after all.

The most popular proposal to emerge from the survey was simply the removal of three little words in the current regulation: “under one roof.”

More than 80 percent of schools favored removing the phrase “under one roof” from Regulation II, Section 11(H) 2. a., which means as long as only three or four students are receiving coaching, then others may be in the facility working on conditioning, or in groups on their own.

Receiving close to 70 percent support from schools is the prospect of removing the portion of Handbook Interpretation 237 which currently prohibits schools from setting up rotations. This would allow a coach to work with dozens of players, three and four at a time.

And, Robertson says, in less time than coaches are currently expending.

“Most high school coaches already commit an enormous amount of time to the offseason development of student-athletes,” he said. “By removing the limit on number of athletes they can have contact with at one time and by placing a limit on the number of dates they can actually have this direct instructional contact, the net gain will be fewer dates, but with a greater impact.”

Rashid forecasts slight modifications of current rules rather than wholesale changes, at least in the near future.

“It wouldn’t surprise me if a few changes come sooner than later,” Rashid said. “One, allow rotations in the three- or four-player rule. Two, allow more than three kids under one roof as long as only three kids are receiving coaching. These two are a broader interpretations of our current rules.”

Simpler could be the answer. Perhaps over the course of time, in trying to be everything to all schools, the rule became more difficult for schools to follow, and for the MHSAA to oversee. Outside influences that could not have been predicted a generation ago have crept into the picture as well.

“These rules are very old, and that doesn’t mean not good,” Rashid said. “They were written at a time when the majority of students played multiple sports; before students began playing in 3rd and 4th grades, and before the non-school sports explosion.”

Even with the current trends and abundance of choices for some athletes, there are strong feelings from various leaders to leave things status quo.

“Our staff and league believes there needs to be a greater emphasis on the current rules with stronger punishments,” Bush said. “The answer is to enforce to current rules that we have, and not change the rules.”

There is a certain irony to this topic in front of athletic administrators and coaches, who spend so many hours in the here and now; in-season, in practices, in games.

“Who would think that what you do out of season could be the most critical piece of school sports discussion that we’ve had?” Rashid ponders. “It’s not what happens during the season, but in the offseason, that might be at the core of encouraging and maintaining school sports participation.”

Current Out-of-Season Rule (Three- or Four-Player Rule)

From MHSAA Handbook, Regulation II, Section 11(H):

2. These limitations out of season apply to coaches:

a. Outside the school season during the school year (from Monday the week of Aug. 15 through the Sunday after Memorial Day observed), school coaches are prohibited from providing coaching at any one time under one roof, facility or campus to more than three (or four) students in grades 7-12 of the district or cooperative program for which they coach (four students if the coaching does not involve practice or competition with students or others not enrolled in that school district). This applies only to the specific sport(s) coached by the coach, but it applies to all levels, junior high/middle school and high school, and both genders, whether the coach is paid or volunteer (e.g., a volunteer JV boys soccer coach may not work with more than three girls in grades 7-12 outside the girls soccer season during the school year).

Johnston Retires as Winningest Coach, Much More to Beaverton Dream He Built

By

Paul Costanzo

Special for MHSAA.com

March 15, 2024

Before Roy Johnston left the court that bears his name for the final time as Beaverton head boys basketball coach on Feb. 23, 1,500-plus fans, family and current and former players had one more chant.

It wasn’t the name of the coach they all adored after he wrapped up the winningest career in MHSAA basketball history. It wasn’t even the school song, or a slogan.

It wasn’t the name of the coach they all adored after he wrapped up the winningest career in MHSAA basketball history. It wasn’t even the school song, or a slogan.

With Johnston pumping a raised fist, the community chanted “Judy” to honor his wife, who could not be at the game or celebration as she was battling cancer.

It was a fitting tribute to the woman behind the coach who became more than the face of the community, and one last opportunity for those fans to say thank you to her for her own efforts and sacrifices in helping the Beaverton become something pulled straight from the movie screen – the small-town sports tale complete with the iconic coach in the lead role and generations of locals living their dedication by filling the stands for every game.

Judy Johnston passed away this past Saturday, a little more than two weeks after the ceremony that honored her husband. She was 81.

All interviews for this story were completed prior to her passing, but a common theme when talking about Johnston’s 50-year career and importance to Beaverton was that the entire family, specifically Judy, had played a big role.

“His family has put forth an incredible amount of effort into our community,” said former player Brent Mishler. “In basketball and in general.”

Family is at the center of Johnston and Beaverton’s immense success over his 50 years. Not only has he coached multiple generations of several Beaverton families – including three generations of Mishlers – but he’s coached his own children, and grandchildren.

Small town programs often rely on players who have grown up around them and together, and Beaverton has that in spades.

“It was a dream,” former player and Johnston’s co-coach, Shad Woodruff, said of having his son Layk play for Johnston. “I got to play for Roy and be part of all that Beaverton basketball is – it’s not just a sport around here. We have video of (Layk) dribbling a basketball in the gym literally before he could walk. He’s been the little guy that always looked up to (Roy’s grandsons) Spencer Johnston and Carter Johnston, so just to be a part of Beaverton basketball is special.

“It’s like when your kid gets there, you’re giving your kid to the community for a while and saying, ‘Here you go.’ It’s amazing to watch your son out there, especially in a community like ours. Roy has created this thing with Beaverton basketball where every Friday night, it’s like church. Everybody’s there.”

“It’s like when your kid gets there, you’re giving your kid to the community for a while and saying, ‘Here you go.’ It’s amazing to watch your son out there, especially in a community like ours. Roy has created this thing with Beaverton basketball where every Friday night, it’s like church. Everybody’s there.”

The numbers behind Johnston’s career, which started in 1966 in Yale, are remarkable. He holds the MHSAA record for wins by a boys basketball coach at 833, the vast majority coming at Beaverton, the program he took over in 1974.

The Beavers won 21 conference titles, 17 District titles and five Regional titles during Johnston’s 50 years, adding a run to the MHSAA Semifinals in 1984.

Just six of Johnston’s seasons ended in records below .500, and in a fitting tribute to their coach, this year’s Beavers scratched and clawed their way to a five-game win streak at the end of the season to ensure his last wouldn’t be No. 7, finishing the year 12-12 with a loss to Beal City in the District Final.

Included in that streak was a 54-45 victory over rival Gladwin on the night Johnston was honored. The Beavers trailed by as many as nine during the second half before rallying to win, led by a 26-rebound performance from 6-foot, 1½-inch senior Reese Longstreth, who Woodruff called the epitome of a Beaverton basketball player.

“I’ve been fortunate to be around Roy for 40 years, and I’ve seen a lot of great wins, especially in that gym,” Woodruff said. “I can’t put anything above that one.”

Layk Woodruff made the final basket in the game, which will forever be the final basket made in Roy F. Johnston Gymnasium during the Johnston era.

“It was super emotional, I’d say, for a bunch of reasons,” Layk Woodruff said of the game. “We felt like it was our responsibility, we had to that game for Roy. It was a rivalry game, last home game of the year – there were a lot of emotions when that game ended. I didn’t even think about (hitting the final shot) until a couple days later. Now that I get to think about it, it’s pretty cool to say that was me. I’ll always remember that.”

One celebration led to another, as Johnston’s retirement ceremony followed the game. A tribute video created by Beaverton graduate Jason Brown, who owns a digital media company, and narrated by longtime Beaverton public address announcer Scott Govitz was played. Govitz admitted to getting choked up at times while recording the video.

“There were a couple times where I did more than one take,” he said.

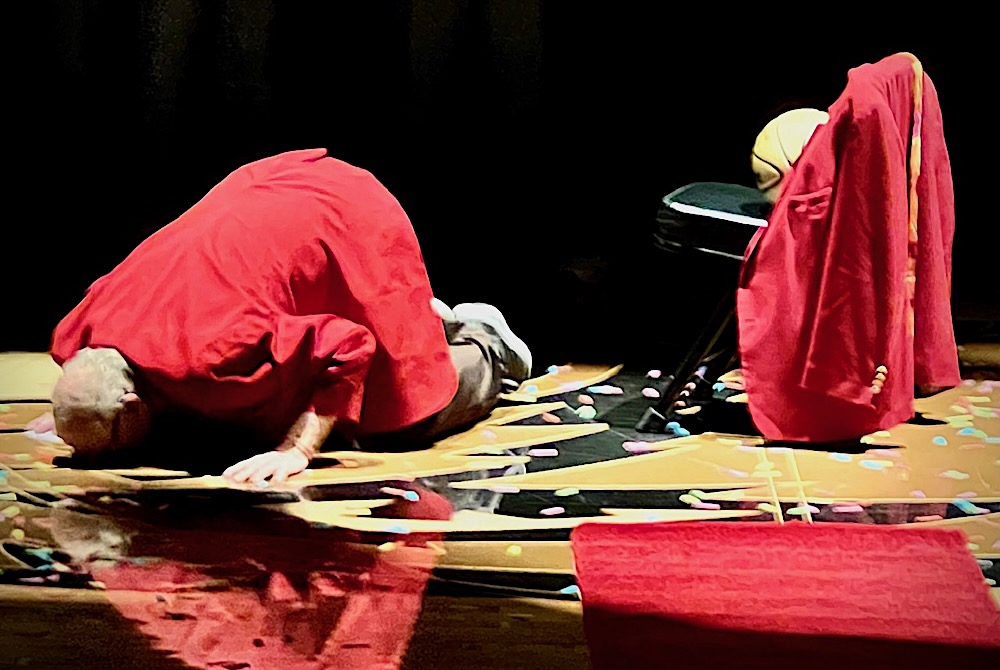

Govitz was at the center of a massive effort to create the ceremony, with support from athletic director Will Gaudard, school staff and members of the community, including multiple businesses and organizations. Govitz had arranged for special lighting and video screens for the presentation. Special tickets were printed for the night – which also happened to be Beaverton’s Hall of Fame night. Following the video, a spotlight was shone on center court, where a single chair sat, one of Johnston’s vintage red blazers draped over its back.

The more than 100 former players who had come to celebrate their coach each had a glow stick they cracked on, and walked through the darkness to surround the chair.

Then Johnston walked the red carpet – much like his starters have for years when being introduced prior to games – and addressed the crowd.

He didn’t speak for long, but as Johnston so often does, he hit all the right notes, mixing gratitude with humor.

“Gladwin County is a great place to raise a good family,” Johnston said after thanking the traveling contingent from Gladwin.

“I want to thank everyone for a great run. Fifty years. A great run.”

For outsiders, it was a chance to see the softer side of Johnston rather than the man intensely patrolling the sidelines during games. It was a glimpse at the man that handed out suckers before games to every kid in attendance.

“He belonged on an episode of ‘Grumpy Old Men,’ and he still could play the role,” Govitz said with a laugh. “He would always say, ‘Don’t listen to the way I say it, listen to what I say.’ He just wants you to do things correctly. His players, maybe they didn’t adore it at the time, but they adore it now. Being a part of that program taught them more than basketball skills. … What will happen, once they leave, they find that great respect for it. And, he does things quietly that no one ever knows or sees – helping someone in need, especially the ones in college, checking up on them or sending them some money. That helps build a program and build relationships. He said in his last speech that it’s about getting along with others. If you can’t get along well with others, you can’t get along. That’s what it’s about.”

“He belonged on an episode of ‘Grumpy Old Men,’ and he still could play the role,” Govitz said with a laugh. “He would always say, ‘Don’t listen to the way I say it, listen to what I say.’ He just wants you to do things correctly. His players, maybe they didn’t adore it at the time, but they adore it now. Being a part of that program taught them more than basketball skills. … What will happen, once they leave, they find that great respect for it. And, he does things quietly that no one ever knows or sees – helping someone in need, especially the ones in college, checking up on them or sending them some money. That helps build a program and build relationships. He said in his last speech that it’s about getting along with others. If you can’t get along well with others, you can’t get along. That’s what it’s about.”

Mishler echoed that sentiment, and some of the memories that stick out most to the 2002 graduate were when Johnston got after him in his own special way.

“Playing for him was a privilege,” said Mishler, whose father Steve played for Johnston in the ’70s, and his son Cameron played through 2021. “The life lessons he taught set you up for success in life for the future. ‘You need to hear what I’m saying, not the method I’m saying it.’ That’s so true. Being honest and having expectations, and expecting people to hit those expectations, is not a bad thing.”

After Johnston was done speaking, he knelt down and kissed the floor to say goodbye to the job he’s done for most of his life, and in a way, thank you, to the community he helped create and that he’ll now need more than ever.

“Roy’s good at making you feel like he’s not big on that stuff (being recognized), and he isn’t, but he definitely does appreciate it,” Shad Woodruff said. “He understands how important he is to the community, and that he’s done something really special. He understands what he’s done is a pretty big feat, but he doesn’t talk about it. He doesn’t brag about it.”

Paul Costanzo served as a sportswriter at The Port Huron Times Herald from 2006-15, including three years as lead sportswriter, and prior to that as sports editor at the Hillsdale Daily News from 2005-06. He can be reached at [email protected] with story ideas for Genesee, Lapeer, St. Clair, Sanilac, Huron, Tuscola, Saginaw, Bay, Arenac, Midland and Gladwin counties.

Paul Costanzo served as a sportswriter at The Port Huron Times Herald from 2006-15, including three years as lead sportswriter, and prior to that as sports editor at the Hillsdale Daily News from 2005-06. He can be reached at [email protected] with story ideas for Genesee, Lapeer, St. Clair, Sanilac, Huron, Tuscola, Saginaw, Bay, Arenac, Midland and Gladwin counties.

PHOTOS (Top) Beaverton boys basketball coach Roy Johnston kisses the court that bears his name during a celebration of his retirement Feb. 23. (Middle) This season’s team stands at the entrance to town with signs announcing the program and coach’s successes. (Below) Johnston takes a photo with three generations of Mishlers – Cameron, Brent and Steve. (Top photo by Stephanie Johnston.)