Get on Your Feet for Our Great Games

January 27, 2017

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

Somewhere along the winding road in the long history of interscholastic athletics, gradual change has brought our product to a crossroads.

We, in this business of developing the minds, character and bodies of student-athletes, still understand the far-reaching benefits of school-based sports, and the mission of our programs. We understand their importance to community, the incomparable entertainment value for spectators, the bonds built between teacher and student that an hour a day in the classroom usually can’t match, and the memories and lessons that last a lifetime.

Somewhere along the way, however, some of the allure seems to have faded in the eyes and minds of others.

• Perhaps it’s the many options available to today’s young people, both in and out of athletics. Where once school sports and a letter jacket were THE thing, now it’s just another thing, with travel programs, virtual reality games, nonstop cable sports coverage and social media competing to fill free time.

• Maybe it’s parents, chasing the misguided dream of athletic scholarships for their children and in the process doting on the promises of untrained coaches intent on building their pocket books and reputations over building fundamentals and teamwork in kids.

• It could be that sensational stories from professional and collegiate levels warning of long-range effects of concussions and other sports injuries are causing fear in many parents who are making athletic participation decisions for their children.

• It’s possible that those once relied upon to spread the good word of our good work – our friends in the media – are far fewer. Administrators and coaches alike were once on a first-name basis with sportswriters in every community across Michigan. When a feel-good story took place, we knew whom to call to trumpet the news, and when the big game took place, they were sure to be there. The collapse and contraction of newspapers and the rise of faceless bloggers has delivered a blow.

• And, what of respect for authority? We are losing the keepers of our games – the contest officials – in bunches each year. People see the assaults, both verbal and physical, on these special men and women who give far more of their time than they are compensated for and figure it can’t be worth it to become an official, or to continue.

Ultimately, how we got here no longer matters. It’s what we do next. The focus for the 2016-17 school year is to define and defend educational athletics. We know that educational athletics is the best option. We are certain specialization is becoming a real health and safety issue, as real as concussions. We emphasize safety and risk management through our rules and regulations. We will utilize current media to tell our story. In doing so, maybe we can increase our pool of officials as well.

The following reveals the plan.

Teaching the Teachers

The 2016-17 school year is featuring a multi-faceted plan to Define and Defend Educational Athletics across Michigan, and one of the most critical strides aims at insuring that all varsity coaches – the educators of our programs – receive the proper instruction to pass along the mission of school-based sports to all involved, from students to parents to administrators.

For the first time each first-time varsity head coach of an MHSAA tournament sport needs to have completed Level 1 or 2 of the MHSAA’s comprehensive Coaches Advancement Program, the acclaimed continuing education program for school coaches.

Arming those most closely involved with student-athletes with proper perspective will go a long way in securing the future of interscholastic athletics.

“The role of a secondary school coach is so much more complex than it first appears, and it reaches beyond the responsibility of teaching skills to athletes,” said MHSAA assistant director Kathy Vruggink Westdorp, who oversees the CAP program. “The coach is first and foremost a teacher – that educational leader in an athletic setting – and it is often this coach’s responsibility to reinforce the connection between sports and academics. This defines the MHSAA brand of athletics.”

The connection between sports and academics cannot be overstated, and those sharing the hallways on a daily basis observe positive effects when students see that coaches show concern for their well-being beyond the playing surfaces.

Dan Hutcheson is in his first year as an assistant director at the MHSAA following a decade as athletic director at Howell High School. Prior to that, he served as the Highlanders’ wrestling coach. He knows first-hand the importance of the coach-student relationship.

“As a coach who’s in the building on staff, I know that I’m going to be in contact with my kids every day in class or in the hallways,” Hutcheson said. “When kids see that you care about them beyond the classrooms and fields or gyms, it can equate to improved academics. That is something other sports organizations don’t have.”

During the last three years alone, more than 1,800 individuals each year have attended CAP courses ranging from Levels 1-8, receiving instruction on topics such as “The Coach as Teacher,” to “Psychology of Coaching,” to “Effectively Working with Parents.” These are just three of the 18 courses making a difference in coaches statewide, and those attendance numbers will rise with this year’s requirement.

While some might see the word “requirement” as an added helping onto the already full plates of those who dedicate so much free time, such regulations add value and help define school programs.

“I believe we have a better sense of the bigger picture. Sure, our coaches want to win. But compared to travel sports, it is more educationally sound,” said Tim Ritsema, athletic director at Zeeland East High School, who serves as one of the MHSAA’s CAP instructors. “For those coaches who complete CAP, it gives their profession more credibility – it tells athletes, parents and the community that they take this seriously and want to be knowledgeable in the best practices. In travel ball, there are no regulations on coaches, it costs a lot more, and there can be selfish agendas. Our coaches are ‘All In.’ They recognize the long-lasting impact that they have on our student-athletes.”

Fellow CAP instructor Mike Garvey, athletic director at Kalamazoo Hackett Catholic Prep, sees the same enthusiasm during his experiences in front of the diverse groups of coaches.

“I see buy-in. Coaches of all ages, with a tremendous range of experience, have shared that they learned, that they have gained insight into the profession,” Garvey said. “I had a coach contact me about a couple of theories presented and indicated that it helped her team in two categories: they had more fun and they performed better. It also drew praise for her from the parents.”

Proven results from the methods employed are a big factor in gaining repeat attendees and spreading the word to coaches who have yet to attend CAP. Nothing increases credibility like positive results and peer recommendation.

A couple other factors contribute to the success, including willingness to participate and the widespread availability of courses throughout the state.

“The best sessions are when the majority of the coaching staff is actively participating, and it doesn't always need to be positive; that seems to add to the program,” notes CAP instructor Karen Leinaar, athletic director at Bear Lake HS. “Sometimes this is the first time all the coaches have actively talked about their philosophy, and sharing just makes it more ‘real.’ Hearing from others that they are doing it right is a big affirmation. Making the program available within a reasonable distance also assists in participation.”

CAP also plays a pivotal role in indoctrinating those outside the school setting to the purpose of school-based sports. Non-faculty coaches might have different roots than faculty coaches, but receive the same messages to take with them.

“There really is not a big difference between faculty and non-faculty coaches in the appreciation for coaches education,” Westdorp said. “We have seen 40-year veterans and first-year protégés indicate similar impact regarding the message of educational athletics.

“However, the non-faculty coaches are definitely better linked to their school and the culture of their school after taking CAP. Each module contains the Ten Basic Beliefs of Michigan Interscholastic Athletics. The very first module in CAP 1 is entitled ‘Coaches Make the Difference,’ and works toward the development of a coaching philosophy, core beliefs, understanding your personal reasons for coaching, promoting high expectations and creating team culture. It includes exercises in making difficult decisions, why there are rules and creating team culture.”

Some of the residual effect might be that today’s coaches will become tomorrow’s administrators, a movement which some sense has stalled in recent years.

The National Federation of State High School Associations recently enlisted global communications marketing firm, Edelman, to assist in rolling out a national campaign this fall to elevate awareness of the NFHS and educational athletics.

“In many cases, we need to re-educate our own people,” NFHS Executive Director Bob Gardner said. “We don’t see coaches moving to principal and athletic director jobs much as we once did.”

In Michigan, CAP is assisting in that way.

“We have several athletic administrators, principals and superintendents who recognize the value of their coaches within the building,” Westdorp said. “Many of these administrators have been in CAP sessions and are utilizing the materials. They want trained coaches who know how to deal with student-athletes in regards to safety, sportsmanship and skill development.”

Communication is key to CAP’s success, not only from instructors to the coaches in attendance, but in turn from coach back to other coaches, students, parents and administration moving forward. That’s how the mission of school sports persists.

“I stress that communication is one of the most important things coaches need to do,” Ritsema said. “Being a poor communicator allows for many things to go bad.”

Zeeland East and Bear Lake are classes apart in enrollment, but the rule of communication is universal.

“I am lucky being in a small school; we have very few questions to our rules,” Leinaar said. “I know others that have huge issues, but many have caused their own because they lacked the art of communication. Share with everyone. Make Grandma understand. You’ll not necessarily get 100 percent support, but at least there will be a shared understanding and expectation.”

Ultimately, the component of school sports which ranks above all else is the participants.

“We emphasize working with young people and teaching. Working with young people and leading,” Garvey said, “and keeping young people as the reason for the activity.”

Well-Rounded Task

The MHSAA organized a multi-sport participation task force during 2015-16 to identify the main sources of sports specialization and to generate methods to encourage greater participation in a variety of activities.

During the first meeting last April, Dr. Tony Moreno of Eastern Michigan University and Dr. Brooke Lemmen of the Michigan State University Sports Medicine Clinic each cited research which is inconclusive if specialization is the path to the elite level of sports, but is conclusive that specialization is the path to chronic, long-term negative effects.

The mission ahead for the task force is to change the culture in and around their schools.

“There’s a misconception that, ‘I have to only participate in that one sport to get to that next level,’” Hutcheson said. “But, when you hear college coaches talk, they want the kids who are athletes, who participated in more than one thing.

“I’d hear kids say, ‘I just want to lift weights out-of-season.’ Well, what do you do when you’re tired of lifting weights? You put them on the ground and rest. If you want to be a competitor, you need to compete. Playing another sport provides the opportunity to continue competing and growing as a competitor.”

While the committee discussed potential plans for such items as online resources, printed material and social media discussion to generate heightened awareness, those avenues have already been traveled to various lengths. In fact, the mission has changed little over the years.

“The most remarkable thing is that when I reviewed a couple of old videos we produced on the value of multi-sport participation about 10 years ago, our message really hasn't changed,” said MHSAA Communications Director John Johnson. “We now need to emphasize the injury factor – which is now so much more well-documented – and the fact that an increasing number of recognizable faces at higher levels are now endorsing the playing of multiple sports at youth levels.”

The trick is to develop the most effective delivery system and target those who most need exposure to the topic: coaches and parents.

“The task force sees educating parents as a priority, informing them of the dangers of early specialization in terms of burnout and injuries, as well as the financial burden families take on to advance their child towards a possible scholarship,” said long-time Traverse City Area Public Schools administrator and task force member Patti Tibaldi. “Parents need to understand that only one percent of high school athletes will receive athletic scholarships. Educational athletics should address the needs of the other 99 percent, don't you think?”

In many communities around Michigan, multi-sport athletes are not simply an added benefit; they are a must for programs to exist.

“I’m from a small school,” said Bronson athletic director and task force member Jean LaClair. “For our teams to be successful across the board, we need our student-athletes participating in multiple sports. We had a volleyball and softball team both make the state championship games, and seven kids were on both rosters! And, playing in a championship game, with the small-town support, is something you will never emulate in a club sport.”

It takes support from parents and coaches to build successful school sports programs, and administrators play a pivotal role in steering the ship.

“The biggest thing we discuss is the multi-sport athlete in our high school,” Ritsema said. “Luckily, our coaches are on the same page, and we deliver that message unified to our athletes and parents.”

Those involved with the task force understand the importance of the issues. It’s time for the choir to do the preaching, and project the chords beyond their buildings.

“Multi-sport participation within the school-based system teaches students the valuable lessons athletics should provide: how to work with different groups of people, the discipline of practice, how to respond from failure, how to understand and accept different roles within each sport, recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of each coach and teammate,” said Tibaldi. “School-based sports have a fundamental belief system that, while every sport has its individual differences, all sports need to comply with the philosophy of educational athletics adopted by the school district.”

As Johnson points out, the sooner that message reaches its target, the better.

“We need to literally reach the bottom of the food chain: elementary school kids who play sports, and their parents,” he said.

To that end, the MHSAA is focusing efforts in two ways during 2016-17: increased communication with its junior high/middle school membership, and the formation of regional strike teams.

Going Back to the Future

As the MHSAA moves forward with several initiatives this school year to help in defining and defending educational athletics, some staff members will be working their way backward – in age, that is.

Various findings in recent years through committees, task forces and personal experiences reveal that often times students are reaching secondary schools without positive prior experiences in school sports. That is about to change.

During the 2016-17 school year, the MHSAA is conducting two Junior High/Middle School Committee meetings rather than one, with an emphasis on the MHSAA more closely aligning itself with various JH/MS events through sponsorship efforts.

“The multi-sport task force has been a great discussion tool,” said MHSAA Assistant Director Cody Inglis, who oversees the JH/MS Committee. “You see that no matter the size of the school, everyone has the same problem; it’s become a true health and safety problem. Kids are specializing too soon and too often.”

One of the steps to help combat the trend is to reach children, parents and coaches before they hit the high school hallways.

“The task force recognizes that parents want to do what is best for their children,” Tibaldi said. “Our recommendations include finding ways for schools to offer earlier and better programming, stressing the development of overall physical skills versus the constant competition at an early age which is leading to an exodus from athletics by the age of 13.”

More than 700 junior high/middle schools across Michigan were members of the MHSAA in 2015-16. But just how many participants and parents – or even coaches at that level – are aware of the benefits afforded by that membership? The answer is likely a stark minority. It is the MHSAA’s charge to be more visible in the coming years.

“We’ll discuss becoming a presenting sponsor at some pre-existing league meets at the junior high/middle school level, whether it be track, basketball, cross country or any sport,” Inglis said. “We want to get into those existing leagues and conferences to have a presence.

“We could help financially, to offset the cost of officials and medals, for instance. And, we can brand those events from an educational athletic standpoint, versus the youth sport model which most kids that age have experienced. The goal is to give them a perspective they’ve yet to have in school-based sports. We want to make sure putting on a school uniform is a positive experience.”

Of course, biggest proponents of school sports are those who have dedicated hours, years and careers to the product. Those people, the ones the MHSAA leans on and appreciates the most, will be called upon again to deliver a huge assist at youth levels via forthcoming “Regional Strike Teams.”

“These local teams could be veteran or retired ADs in various areas who understand educational athletics and are familiar with junior high/middle schools in their communities,” Inglis said. “They can emphasize sportsmanship and multi-sport involvement so we can get in on the ground floor.”

The formation of these liaisons between the MHSAA and its youngest members will be discussed at length during the 2016-17 school year.

The junior high/middle school gyms and fields are not only stocked with future high school students, but they also offer a valuable forum for officials recruitment, training and retention, another critical piece to the welfare of school sports.

“With our Regional Strike Teams of people connected to schools and local officials associations, we can increase the connections made at the local, personal level to attract more people into officiating,” said MHSAA Assistant Director Mark Uyl, who oversees the MHSAA’s services to registered officials. “The members of the Strike Teams will know what events are going in an area of the state which could be conducive to officials recruitment events. The best way to recruit is at the local level between people with shared interests, and the Regional Strike folks can make these local connections.”

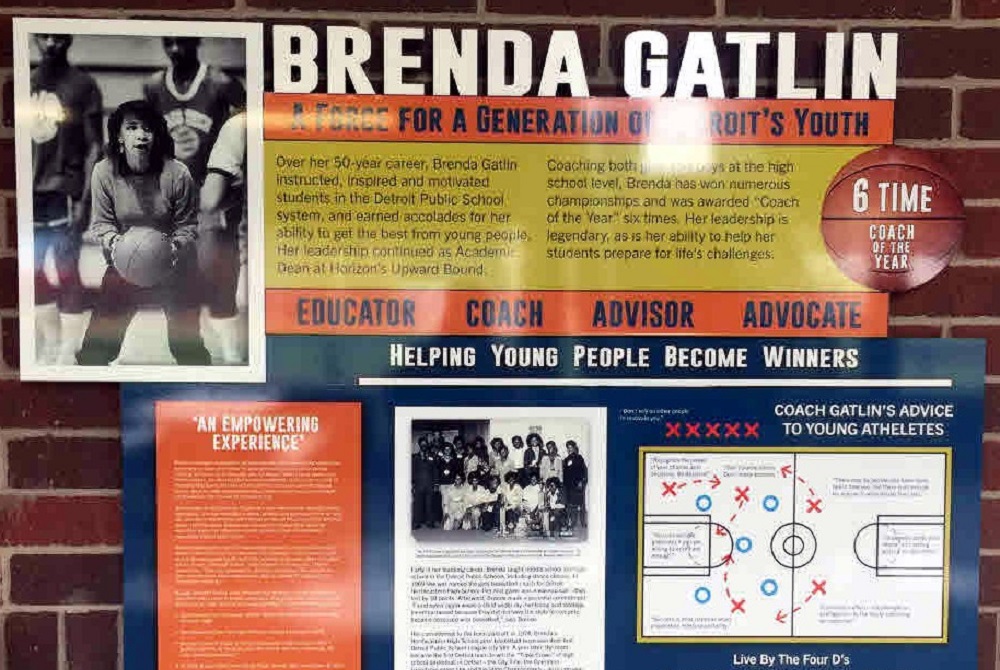

The 6 Ds of Brenda Gatlin - Master of the Coaching Dance

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

September 30, 2021

She is remembered fondly as one of the greatest to ever coach in the Detroit Public School League and the State of Michigan, yet you won’t see Brenda Gatlin’s name among the leaders in all-time basketball victories. A search of the MHSAA List of Girls Basketball Champions displays her name only once.

You will, however, find Gatlin’s name in one most unexpected, yet fitting place.

The Corner Ballpark, the redevelopment of the site of historic Tiger Stadium – located at Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood – includes the Hank Greenberg Walk of Heroes. Opened in 2019, the “exhibit features 12 stories of Michigan citizens who displayed character, innovation and trailblazing spirit in the sports field and the community at large.”

The Corner tribute, as one might expect, includes Tigers greats Greenberg, Hank Aguirre, and Willie Horton. Norman ‘Turkey’ Stearns, a baseball Hall of Fame member and legend with the Detroit Stars of the Negro League is another honoree.

Mixed in with the other eight is Gatlin. The honor is most deserved.

Champion in Life

Gatlin never expected to coach basketball.

“I was a dance teacher,” she told The Southeastern Jungaleer, a public forum for the students and community of Southeastern High School published in the Detroit Free Press in 2009 at the time of her retirement after 43 years in public education. “Early in my teaching career I was asked to coach. I knew nothing about basketball.”

The daughter of a gifted clarinetist, who taught at Lincoln University then left for Virginia State College (VSC) where he became the Head of the Music Department, Gatlin was born in Jefferson City, Mo., to Dr. F Nathaniel Gatlin and his bride, Mildred Pettiford Gatlin, an elementary education teacher and reading specialist. The family moved to Petersburg, Va., when her father accepted a position at VSC. Brenda graduated from segregated Peabody High School – the earliest publicly-funded high school for African Americans in Virginia.

“Dad was strict and no nonsense – mom, nurturing and loving,” Gatlin recently recalled of her parents. “Dad was loving also, but his life was filled with so many trials and tribulations. It would take too much time to explain. He graduated from Oberlin Conservative College of Music, Northwestern University (master’s), and Columbia University (doctorate). Mom graduated from Lincoln University (bachelor’s) and VSC (master’s).

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

Brenda began teaching in Detroit at Barbour Middle School in 1966: “I started my tenure with Detroit Public Schools immediately upon graduating.”

“When I came to Detroit, I only planned to stay here three years. But I fell in love with the city,” she told the Free Press in 1976.

Her next career move was to Detroit Northeastern for the 1969-70 school year.

“I went to the Office of Human Resources and they had an opening at Northeastern high school for a Health and Physical Education and Dance Teacher. All of my classes were dance. I was elated. … My love was always Ballet, and Modern Dance,” she said. “At one of our department meetings, Norm Morris, Department Head, said we need a girls’ basketball coach.”

Both programs were long-established athletic department activities with histories that dated back decades at the school, once located on Detroit’s Lower East Side.

“I was in the midst of creating a choreography for the ALL-City Dance Concert that had been scheduled. Mr. Morris knocked me for a loop and said, Ms. Gatlin, you will coach the girls’ basketball team …” she recalled.

“I never in my wildest dreams ever thought that I would have to coach any sports, especially girls basketball.”

Making of a Coach

As a health and physical education major, Gatlin had played some intramurals and learned about sports mechanics, policies and procedures, and rules and regulations while in college.

“I was familiar with the 6-player rule, but the year I started coaching, the rules for girls had changed from 6-on-6 with a roving player to 5-on-5 with unlimited dribbling” she said. “Well needless to say, I choreographed my plays; I knew about movement. I studied the game as much as possible, but my focus was on dance.

“(I)n our first two seasons, we played only five games (each season),” she said to the Free Press, remembering those days when the girls played only against other Detroit city schools.

“The home team (supplied) oranges at half time, and cookies and milk for a social after the game,” she said recently, describing a completely different era. “You can imagine those girls scrapping and running down the court and then having to sit with the opposing team at the end for a social.”

In 2002, she recalled her opening contest as a coach for Lorne Plant at State Champs: “(Our opponent) proceeded to beat us by about 30 points.”

That game was a turning point.

“When we hosted Central high school, under the coaching jurisdiction of Doris Jones, everything changed. … I greeted Coach Jones. Without a greeting, she immediately said, ‘Where is the gym?’ I knew we were in big trouble.

“Sitting there watching my choreographed plays and movements … watching the determination on the faces of my girls – who looked over to me for answers, which I had none, watching my girls continue to fight and battle, even though they were down by 30 points, changed my life and focus. They just didn’t have the skills to compete. I vowed at that moment, ‘no students under my tutelage would be demoralized or embarrassed because they did not, at least, have the skills to compete.’ That game did it, and I owe it all to Coach Doris Jones. I rolled-up my sleeves and got to work.”

Title IX

The advent of Title IX meant things were changing in girls athletics all over the country.

“I remember attending myriad meetings at Wigle Recreation Center with other Detroit female physical education teachers. (At that time, women were the only ones allowed to coach girls in athletics in Michigan). The purpose of the meeting was to discuss whether girls should adopt the same 10 game schedule as the boys,” she said. “Some of the older coaches, and teachers had comments like: ‘This will be too difficult on the female body … studies show that the female uterus will drop if girls are allowed to run up and down the court for any length of time.’ We had to sit and listen to comments such as that. However, we voted that girls should be provided the same opportunities as boys. I suppose Christine Whitehead, Assistant Director of Athletics, provided Dr. Robert Luby (director of the Department of Health, Physical Education, and Safety for Detroit Public Schools from 1962 to 1983) with our sentiments. With Title IX it was a given. Some people still fought it.”

“Subsequent to the fiasco with Central, I had commenced the process of enhancing my knowledge of the rules and skills inherent in the game of basketball defensively and offensively. I discovered (UCLA coach) John Wooden’s books. His books became sort of my ‘Basketball Bibles.’ I became obsessed with the game. I woke up with basketball, went to sleep with basketball.

“And further, the recreation centers were sending us players who had some experience with the game. The Catholic Schools had a feeder program. We did not. So, my hat goes off to Virginia Lawrence and her sister Evalena, Coach Curtis Green, and many others who taught girls at an early age the skills of basketball.”

With the arrival of the federal law, the MHSAA sponsored its first girls basketball tournament in the fall of 1973. Gatlin’s Falconettes were ready.

Led by Hazel Gibson and the talented Williams sisters (Annette, Helen, and Shelia), they were now among the top teams in Detroit.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

In 1974, Northeastern trounced Murray-Wright, 73-27, winning its first Public School League (PSL) regular-season tournament before 500 fans at Wayne State University’s Matthaei Building. Gatlin’s team again ran into Dominican in the MHSAA Tournament, this time in a District Final. The Williams sisters combined for 61 of the Falconettes’ 71 points but fell 74-71 in a foul-filled game.

The defeat was Northeastern’s only loss in 16 games. Senior Lynn Chadwick posted a career-high 28 points to lead Dominican, which would repeat as Class A champ.

“Girls will play their heart out for you,” Gatlin told the Free Press following the season, “if they believe in you and if you treat them fairly.”

Postseason reward came in 1975 when Northeastern topped Dominican in the MHSAA Semifinals, 75-69, then defeated Farmington Our Lady of Mercy, 67-62, to earn the Class A title. Helen Williams scored 31 in the championship game, while Shelia added 20.

“Everybody knows about Shelia and Helen,” Gatlin told the press, “but it was the defense we got from our guards that did the job for us in the second half. We switched from a zone defense to our press and that made the difference.” Northeastern ended the year with a perfect 20-0 record.

Gatlin spent two more seasons at Northeastern before moving on to newly-opened Detroit Renaissance in the fall of 1978.

College Calls

“In 1978, I was asked to teach in a new examination high school,” continued Gatlin, “Renaissance High School (located at Old Catholic Central School). I hesitated because transferring to Renaissance meant no coaching, for Renaissance would not have an athletic program. It would be strictly academic. I enjoyed the fact that I was a part of the planning process in developing plans for the opening of a new school. The whole Renaissance situation was controversial, because many thought Cass (Tech) was enough. The rest is history. Our students were only able to participate in an intramural program, and I taught dance.”

There, she received a call from the athletic director at University of Michigan-Dearborn. Roy Allen, the associate director of health and education for the Detroit Public Schools, had passed on her name as a possible candidate to lead Michigan-Dearborn’s girls basketball team.

“I was able to juggle my teaching responsibilities at Renaissance with my coaching responsibilities at Michigan-Dearborn,” she said. But balancing the coaching duties would become more challenging as time moved on.

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

Return to the PSL

“In 1981, Dr. Remus, the first principal of Renaissance who convinced me to transfer from Northeastern, was asked to become the principal of Cass Tech. Cass was experiencing some issues that they felt Dr. Remus could clear up,” Gatlin said. “Shirley Burke, the successful girls basketball coach at Cass, was stepping down. Cass also needed a dance teacher. Therefore, Dr. Remus said, ‘Ms. Gatlin, I need you at Cass.’ I think I was ready to get back to the high school level. I learned so much more coaching on the collegiate level and had grown extensively. Coach Burke left me with great players.”

When a teacher’s strike in the fall of 1982 threatened the Lady Technicians’ basketball season, Gatlin and her players petitioned Detroit school superintendent Dr. Arthur Jefferson for equal treatment that was afforded the Detroit PSL prep football teams.

“Coaching staffs at Detroit’s 21 high schools have volunteered to continue the football program after hours despite a three-week-old strike,” wrote Joyce Walker-Tyson in the Free Press. “Schools must play a certain number of games to be eligible for tournaments. While there is no similar requirement for girls’ basketball, Title IX … calls for equality in boys’ and girls’ athletics.

“During the teachers’ strike, (the girls were) the ones who went down to talk to the board (of education) all by themselves,” Gatlin told the Free Press’s Mick McCabe

When all 21 of the girls high school coaches volunteered their services, the girls season was saved, although it started late.

Her 1982 team upset No. 2-ranked Trenton in the Regional Final before advancing to the Class A Quarterfinals and falling to Farmington Mercy 38-34 in a thriller.

The season marked the first of three straight PSL championships won by Gatlin’s teams. At Cass Tech she developed a number of all-city and all-state players, including Pamela Dubose (Iowa/Wayne State), Kendra McDonald (Western Michigan), Nikita Lowry (Ohio State), Adrianne Smiley (Ball State), Clarissa Merritt (Ferris State), Sonya Watkins (Houston) – whose father Tommy had been a running back for the Detroit Lions from 1962-67 – Wendy Mingo, Savarior Moss, Yvette Walters, and others.

Expanded Responsibilities, Greater Influence

In the fall of the 1984-85 school year, Gatlin was asked to also coach Cass Tech’s boys team.

“I looked at my staff and hired the best possible person,” said Jeannette Wheatley, Detroit Cass Tech principal in September 1984. “Brenda is an excellent teacher, and she is a marvelous motivator.”

“I see it as a challenge for all female coaches,” Gatlin said to McCabe after the announcement. “But the men have been doing a dual role for years. The Xs and Os are Xs and Os. Basketball is basketball. Outside the strength factor, it’s the same game.”

Gatlin at Cass Tech, Kathy Curtis at Colon, and Carol Brooks at Burr Oak were all in charge of boys varsity teams that winter. They are believed to be the first to do so in Michigan.

She took the job for a year, but delayed her start. The beginning of the boys schedule in 1984 overlapped the girls postseason. (Prior to the 2007-08 school year, girls basketball was played in the fall in Michigan.) Gatlin didn’t want to shortchange her girls.

The Lady Technicians finished with 22 wins against 4 losses that season, advancing to the Class A Semifinals before falling to eventual champion Flint Northwestern. So it was mid-December before she returned to the boys team for the fourth game of the season, a 60-58 win. A young team, Cass Tech finished 10-9 on the year.

Back in 1974, Gatlin told Hal Schram of the Free Press that she wasn’t sure she wanted to spend the rest of her life coaching basketball.

“You have to be a psychologist, a coach and a sociologist to get the complete job done,” she said.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

In 1992, she moved back to Cass Tech, now as an assistant principal. She became principal at Southeastern in 1999, where she stayed until her retirement.

Determination

Today, she continues to practice her belief in the potential of the human being, working with Cranbrook schools and their Horizons-Upward Bound Program as academic dean. There, she helps students from the Detroit metropolitan area who have limited opportunities to enter and succeed in college.

Her life has always been built around four Ds.

“I still use it even with my students in the Cranbrook Horizons-Upward Bound Program,” she said. “When I use the Ds with Basketball, it becomes five Ds: Determination, Dedication, Desire, Discipline, and Defense.

“My players knew that defense wins games; it’s the name of the game. Offense is for the spectators. Defense is for the win. Our chant in our huddle always ended with, ‘The name of the game?’ They would respond with ‘Defense!’ This would be recited several times in the huddle prior to them taking the floor. My players knew that the most important ‘D’ other than defense is discipline.

“... I may have adopted it from my dad. I also used his quote, ‘The difference between resting on the bench and rusting on the bench is u.’ There were a few others.

“You can be dedicated, you can have the determination and the desire, but if you don’t have the discipline, success may not happen.”

The Sixth ‘D’ - Drive

“I get my determination and drive from my dad. My mom was very mild mannered. They were an awesome couple and a great parental balance for my brother Nat and me,” she said, and that drive – the need to teach – remains strong.

“I can’t stop.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

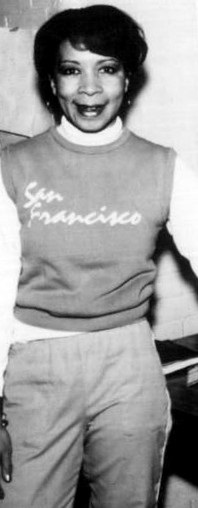

PHOTOS (Top) Brenda Gatlin is among honorees at Detroit’s “Walk of Heroes” display. (2) Gatlin’s first high school position was at Detroit Northeastern, here in 1971. (3) The 1974 Falconettes pose with their first Public School League trophy. (4) Gatlin huddles with the team in 1976. (5) The 1983 Cass Tech team: (Kneeling, left to right) Kim Justice, Ursula Gordon, Andrea Shaw and LaTrece Owens. (Standing, left to right) Coach Brenda Gatlin, Adrienne Smiley, Clarissa Merritt, Wendy Mingo, Kendra McDonald, Nikita Lowry, Kim Wells and Kathy Scates. (6) Gatlin left Cass Tech in 1986 to become athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch from multiple school yearbooks.)