Classes Still Create Hoosier Hysteria

July 27, 2017

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

This is the fourth part in a series on MHSAA tournament classification, past and present, that will be published over the next two weeks. This series originally ran in this spring's edition of MHSAA benchmarks.

Twenty years ago, Bloomington North High School won the Indiana High School Athletic Association boys basketball championship, defeating Delta 75-54 at the RCA Dome in Indianapolis.

The date, March 22, 1997, is at the same time revered and disdained by traditionalists in the state who saw it as the last schoolboy championship game the state would ever host.

That’s how devout the game of basketball, particularly interscholastic basketball, had become in the Hoosier state during the 87 years a state champion – one state champion, to be precise – was crowned.

Following that 1997 season, the IHSAA moved to a four-class system for its roundball tournaments, like so many of its state association counterparts had done years earlier.

It would be shocking to find more than a small percentage of current high school basketball players around the country unfamiliar with the iconic movie Hoosiers, even though the film is now more than 30 years old.

And, the storyline for that blockbuster unfolded more than 30 years prior to its release, when small-town, undermanned Milan High School defeated Muncie Central High School 32-30 in the 1954 IHSAA title game.

Perhaps it’s because of the David vs Goliath notion, or the fame of the movie that replaced Milan with the fictional Hickory and real-life star Bobby Plump with Hollywood hero Jimmy Chitwood, or the simple fact that Indiana had something other states didn’t.

Whatever the reason, plenty of opposition remains to this day to basketball classification in the state.

The fact is, the small rural schools were regularly being beaten handily by the much larger suburban and city schools as the tournament progressed each season.

Small schools also were closing at a rapid rate following the state’s School Reorganization Act in 1959, as students converged on larger, centralized county schools. From 1960 to 2000, the number of schools entering the tournament dropped from 694 to 381, and in 1997 a total of 382 schools and 4,584 athletes began competition at the Sectional level (the first level of the IHSAA Basketball Tournament).

It was at the entry level of the tournament where school administrators felt the pain of the new class system, but not necessarily for the same nostalgic reasons as the fans who either attended or boycotted the tournament.

At the Sectional round of the tournament, the IHSAA was culling just 2 percent of the revenue, with the participating schools splitting the balance. So, when Sectional attendance dropped by 14 percent in that first year of class basketball, many schools realized a financial loss. It was money they had grown to count on in prior years to help fund various aspects of the department.

Schools cumulatively received more than $900,000 from Sectional competition in 1998, but that total was down from more than $1 million in the last year of the single-class tournament.

Yet, the current format provides a great deal more opportunity and realistic chances at championship runs for schools of all enrollments.

To date, 60 additional teams have championship or runner-up trophies on display in school trophy cases around Indiana.

That was the mission in front of then-IHSAA commissioner Bob Gardner (now National Federation executive director) once the board made its decision: to give thousands more student-athletes the opportunity for once-in-a-lifetime experiences.

As any statistician knows, figures can be manipulated to tell any side of a story. Declining attendance in year one of class basketball is such a number.

The truth is tournament attendance had been on a steady downward spiral since its peak of just over 1.5 million in 1962. By the last single-class event in 1997, the total attendance was half that.

The challenge then and today, as it is for all state associations, is to find that delicate balance for those holding onto tradition, those holding onto trophies, and the number of trophies to hand out.

Editor’s Note: Stories from the Fort Wayne Journal Gazette in 1998 and from a 2007 issue of Indianapolis Monthly provided facts in this article.

'Refuse to Lose' Divine Child Set Tone for Teams to Come with 1st Class B Title

By

Brad Emons

Special for MHSAA.com

November 15, 2024

There was no more conjecture, no newspaper or Associated Press polls to determine the state football champions.

The champion was no longer decided on paper, but out on the field as the MHSAA launched its first playoff tournament in 1975.

Only 16 total teams over four classes were invited to the dance.

And a school with an already a rich football heritage in Dearborn Divine Child proved it on the field with a 21-0 win over Saginaw MacArthur in the Class B title game before 4,000 fans at Central Michigan University’s Perry Shorts Stadium in Mount Pleasant.

In the Semifinals, MacArthur had outlasted Flint Ainsworth, 44-38, as senior halfback Mark Neiderquill rushed for 285 yards and four touchdowns, while Divine Child ousted Sturgis, 20-3.

In the frigid championship final on Nov. 22, the Falcons’ defense held MacArthur’s high-octane offense to seven first downs and 74 yards rushing. They caused three turnovers, with two fumble recoveries and an interception leading to all three of their TDs.

“I thought we could move the ball, but MacArthur was tough,” DC coach Bob LaPointe told the Detroit Free Press.

In the second quarter, Pat Doyle returned an interception 28 yards for a TD, and Mike Surmacz added the PAT for a 7-0 Divine Child advantage.

“That first interception really got us rolling,” LaPointe said. “Doyle can run the 40 in 4.9 and speed is what made that touchdown. But he got good blocking, too.”

“That first interception really got us rolling,” LaPointe said. “Doyle can run the 40 in 4.9 and speed is what made that touchdown. But he got good blocking, too.”

Two minutes later, Mike Wiacek gave DC another scoring opportunity when he recovered a MacArthur fumble at the Generals’ 24. Nine plays later, senior quarterback Dan Faletti swept right end and scored on a three-yard bootleg for a 14-0 lead.

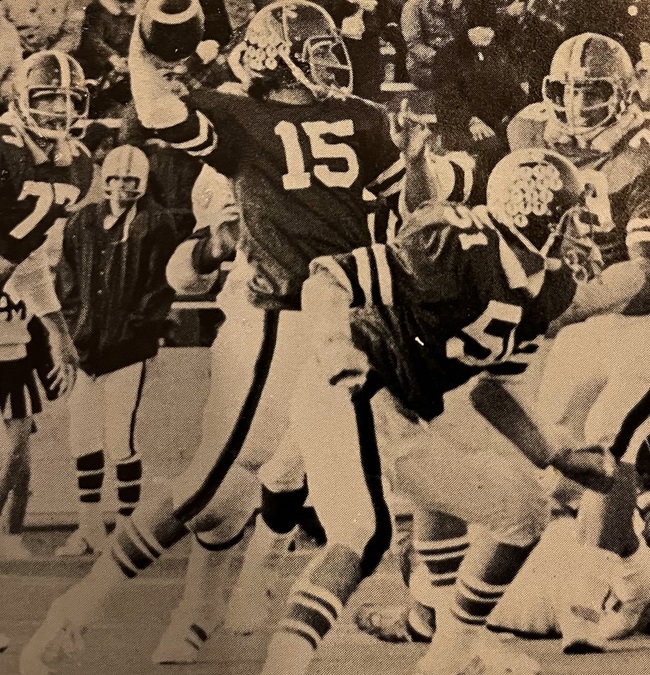

“The big thing is that they had a good running back that we had to make sure we kept under control,” said Faletti, who went on to play at Eastern Michigan University before a neck injury prematurely ended his career as a sophomore. “We pretty much got the lead, and Bob was conservative. I just remember scoring that touchdown, and my picture made the paper the next day.”

Neither team could move the ball in the third quarter. There were no first downs.

All-stater Mike Svihra then picked up a fumbled lateral in the fourth quarter and ran 10 yards for the game’s final TD.

“It was not a lot of offense; it was a bitter, cold day,” said Faletti, who went on to work for the Department of Defense for 20 years and Ford Motor Co. before recently retiring. “Bob LaPointe ran a conservative offense. We did ball-control, we didn’t put tons of points on the board ... we didn’t fumble the ball. We didn’t throw interceptions.”

The game, ironically, was played on AstroTurf, not on real grass.

“Everyone makes a bit deal of it, but there really isn’t that much difference,” LaPointe added afterwards. “The only thing I regretted about this game was that I could dress only 44 of my 56 players under the rules. It was tough (to) tell the other 12 they couldn’t suit up.”

An 18-12 loss to Madison Heights Bishop Foley during the final regular-season game, spoiling what would have been an undefeated season in 1974, had left the Falcons distraught – but even more galvanized as they made preparations for the 1975 campaign.

The Falcons also changed their offense in 1975, switching to a triple-option attack that LaPointe got from Notre Dame. The offense proved to be good enough for a 9-0 regular season and an MHSAA playoff berth.

“We were an underdog the whole thing, the whole time, we were the underdog in every big game we played in, but we didn’t allow people to beat us,” said Wes Wishart, who coached the linebackers and offensive line that season before taking over the head coaching reins for the Falcons from 1978-95. “We refused to lose, and that was the motto. From ’74 on those group of kids said, ‘We refuse to lose.’ You use that phrase as a coach all the time, but this group of kids lived it. They were the ones that invented it. When things got tight, ‘refuse, refuse, refuse.’ We’re not backing off from anybody. Great group of young men, great players.”

During the regular season, DC earned victories over highly-touted Flint Powers Catholic (20-14), previously unbeaten Southgate Aquinas (26-12) and Allen Park Cabrini (12-8).

During the regular season, DC earned victories over highly-touted Flint Powers Catholic (20-14), previously unbeaten Southgate Aquinas (26-12) and Allen Park Cabrini (12-8).

That set up a Catholic League Prep Bowl showdown in the final game of the regular season against highly-touted 8-0 Birmingham Brother Rice, which was ranked No. 1 in the final regular-season AP Class A poll.

Although the Falcons were a decided underdog, the AA division champs upended Rice, 7-0, before a packed crowd at Eastern Michigan University’s Rynearson Stadium to snap the Warriors’ 22-game winning streak thanks to Jim Kempinski’s fumble return for a seven-yard touchdown as he snagged the ball in mid-air and never broke stride while crossing into the end zone.

“We played our butts off,” Faletti said. “It was a dog-eat-dog game.”

It was DC’s 11th Catholic League title, but more importantly put the Falcons into the first MHSAA Playoffs against Sturgis in a Semifinal match at C.W. Post Field in Battle Creek.

“I remember everything was brand new; nobody knew what they were doing,” said Wishart, who guided the Falcons to the 1985 Class A crown as their head coach. “Coach LaPointe on Monday had to get the school to get our hotel rooms in Battle Creek.”

Steve Toepper booted a 27-yard field goal for Sturgis to open the scoring, but DC responded with 20 unanswered points.

In the final quarter, DC’s Rick Rogowski scored on a seven-yard run with 9:23 left (after Steve Savini recovered a fumble caused by Joe Wiercioch) followed by a 10-yard TD run by Faletti with only six minutes to go (after Svihra recovered a fumble).

That sent the Falcons into the Final at CMU, where their defense suffocated MacArthur (9-2).

“We kind of ran a special outside zone. We had to quickly change (how) we would defend that. We shut them down,” said Wishart, who spent 50 years in CYO and high school coaching before retiring to live in New York. “There was no doubt, we were more physical than they were. We were blue collar kids. Typical Divine Child kids, hard-working, never give up.

“We believed desperately in defending Divine Child at all costs because we were a smaller school, so we had an attitude that still lingers there today that we all cultivated. We were going to be a physical squad.”

Meanwhile, what made the Falcons special and unique that title season was their “one for all and all for one” attitude.

“Everybody was the same,” Faletti said. “When we went between the lines, we were all equal. As captain, I got to be command as quarterback in the huddle. But off the field we were all equal. We played like 22 seniors. We were ready for this game.”

PHOTOS (Top) Dearborn Divine Child coaches and players receive the Class B championship trophy after winning the inaugural title game in 1975. (Middle) Falcons quarterback Dan Faletti throws a pass during the Final. (Below) Divine Child players and coaches raise their Prep Bowl trophy in celebration. (Championship game photos courtesy of Dearborn Divine Child yearbook. Prep Bowl photo provided by Dan Faletti.)