Singing the Praises of Unsung Heroes

July 2, 2013

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

“Standing in the Shadows of Motown” is a documentary released in 2002 celebrating a group of musicians who called themselves the Funk Brothers.

Never heard of them?

All this unheralded group did was rack up more No. 1 hits than the Rolling Stones, Beatles, Beach Boys and Elvis – combined – during their unparalleled run as the musicians who drove the Motown sound.

Smokey Robinson, Diana Ross, Martha Reeves, Marvin Gaye, et al, took the bows; but it was this group of selfless, tireless, talented artists which thrust the vocalists to the front of the stage.

How quickly we recognize those songs from the first notes of that signature bass; the vibrant siren of horns, and rhythmic snapping of fingers before a single lyric is introduced.

And now, ladies and gentlemen, without further ado, we introduce to you the Funk Brothers (and Sisters) of school sports: the athletic administrators.

The profession calls for selfless, tireless, talented individuals who trumpet the efforts of students, orchestrate harmony among coaches and parents, and set the stage for local, affordable entertainment within their communities.

In Michigan, the group assumes this responsibility with unwavering ambition and enthusiasm, setting a solid foundation for the futures of roughly 300,000 athletic participants annually.

As MHSAA Executive Director Jack Roberts notes, “They don’t try to be the stars of the show, but they are indispensable for letting the stars shine – the student-athletes and their coaches.”

It is a role they cherish, taking nearly as much pride in their school family as their own. It’s both a byproduct and a prerequisite for such a job that commands long hours and a knack for interaction with a wide array of personalities and age groups.

Mostly, it’s the young people who make it all worthwhile. They are, after all, the reason the job exists.

“Just watching so many students grow up from immature kids to young adults who now are very successful, and how they appreciate all the extra time you spent with them is rewarding,” said Marc Sonnenfeld, the district athletic director and dean of discipline at Warren Fitzgerald.

“And most important is the, ‘Thank You,’ you get five or 10 years later for pushing them and teaching them life lessons they will never forget.”

In a position largely devoid of gratitude, it’s little wonder that the smallest displays mean the most.

“Having a coach thank me for supporting them, and watching student growth through athletics mean a lot to me,” said Eve Claar, in her fourth year as athletic director and assistant principal at Ann Arbor Pioneer High School.

Brian Gordon, less than a year into his post as director of athletics and physical education for Novi High School/Middle School after 22 years as a coach and teacher in Royal Oak, also enjoys the impromptu reunions.

“One of the things I most enjoyed was having kids come back to the programs either as a coach, parent, or simply as a fan,” Gordon said. “Nothing is better than when I would look behind the backstop and see some former players watching and laughing while listening to me say the same things I had said 10 years earlier.”

Lessons learned along the way

The typical path taken to the administrative office usually includes a stop or two in the coaching realm, which assists in the transition to life outside the playing boundaries.

“The experiences you bring from coaching are a huge help. I made plenty of mistakes as a coach that I see my own coaches make to this day,” said Chris Ervin, in his seventh year as the activities director at St. Johns High School. “You make mistakes, learn from them, and then make sure not to make them again.

“My philosophy – although not realistic, but certainly something to strive for – is this: we would have much better coaches if these three prerequisites were in place. 1) Coaches must be a parent first; 2) must be an official, and 3) must be an athletic director. If coaches had to have these three experiences before being allowed to coach, they would have a whole new perspective when working with students, parents and officials.”

Having been coaches first, however, lends an appreciation to the task of working with students on a daily basis and an understanding as to how an athletic director can best assist his or her coaches.

“Being a coach helped me to learn time management, and I became better at making relationships. In my job now, it helps me to look at things from the coaches’ viewpoints,” said Christian Wilson, the athletic director and assistant principal at Gaylord High School for 11 years. “As a coach, you have an immediate impact on students; administration involves more interaction with adults.”

A coaching background also can cause an athletic director to re-examine his or her days as a coach, and how they might have had a greater awareness for a former administrator’s tasks.

”The learning curve as the athletic director is massive,” said Gordon. “The job itself is huge. As a coach, you just worry about your own sport. As athletic director, I have more than 70 teams to tend to and over 100 coaches to worry about. Coaching and teaching only scratch the surface of what happens in any athletic office every day, but doing that for more than 20 years has helped the transition significantly.”

It is a viewpoint shared by Ken Mohney, a 14-year director of student activities for both the high school and middle school at Mattawan Consolidated Schools.

“Athletic administration opens up the big picture of the department and school mission. Instead of only focusing on the sport that one coaches, administrators must coordinate a program so that all sports collectively enhance the academic success of the entire school,” said Mohney, who also coached three sports at Mattawan for eight years prior to assuming his current duties. “I miss the connection to players and students that I had as a teacher and coach, as it is much more difficult to create and maintain positive relationships with kids in an administrative role.”

The majority of administrators who have had experience coaching admit to missing the close interaction with students and the opportunity to watch them develop into successful adults.

But, in some respects, the number of lives one can reach as an administrator is multiplied, and the scrapbook moments just take on slightly different poses.

Mike Thayer, athletic director and assistant principal for the past six years at Bay City Western High School following a decade at Merrill, recounts one of his proudest days in the business.

“In 1999, Merrill Community Schools had two MHSAA Scholar-Athletes Award winners,” Thayer said. “The senior class that year had approximately 80 students; yet, they produced two winners of this prestigious award. I miss the student interaction and school pride associated with team-building in coaching, but I do not miss the travel.”

Many duties call

Some ADs, however, might rather board the buses than schedule them, another of the many duties carried out on a weekly basis. In some cases, the position is responsible for school-wide transportation, not just athletic transportation.

Where once being the AD meant just that, the title for many in the profession today also includes a “/” before or after the words “athletic director.” It’s a trend which threatens the growth and quality of athletics in the educational mission of schools.

Even in schools where athletics are well entrenched and participation numbers soar, the people leading the charge are being asked to do more with less, often taking on responsibilities once doled out to two, and even three, individuals.

“Some of the larger challenges for me include the budget, balancing a very large work load, and just having enough time to evaluate coaches and programs effectively,” said Claar, who estimates that 60 percent of Pioneer’s 1,893 students participate in at least one sport.

Figuring conservatively, that’s more than 1,000 students deserving of her utmost attention in their extracurricular pursuits. But Claar also is assistant principal to the entire student body.

“Given the additional responsibilities, ADs are often spread too thin,” she said. “The time constraints make it difficult to complete all of the assigned tasks.”

Sonnenfeld, like so many others, attempts to split the time down the middle, but it rarely works out that way by the time he’s also done monitoring the cafeteria during lunch for a couple periods most days.

“I see between 35-60 kids every morning for various discipline issue,” said Sonnenfeld of one portion of his title. “I usually get to athletics by 1:00. I do as much as I can in the time that I have and then stay late on game days and catch up. And in my free time I’m responsible for renting out the athletic facilities. I make myself leave at a normal time on non-event days so that my family sees me.”

Additionally, he oversees the middle school athletic program, and feels guilty that he can’t devote more time to that level. He needn’t feel that way. If it weren’t for Sonnenfeld, the middle school would not have athletics at all.

“The middle school suffers because I cannot get down there to watch over stuff, but this is better than not having any middle school sports at all. They canceled them for a year, and got rid of the middle school athletic coordinator position and put the duties on me,” he said.

Sonnenfeld is not alone. Duties seem similar across the board.

“I am also responsible for coordinating all building facility usage, fundraising and transportation as well as lunch/hallway supervision before, during and after school,” Mohney said. “Athletic administration alone for grades 6-12 in a Class A school is a full-time, 14-hour-a-day job. It is extremely difficult.”

While not included in his title of activities director, Ervin, too, is expected to mete out discipline and supervise lunches on a regular basis.

“Time is a major obstacle,” Ervin said. “When our assistant principal is out of the building I take on most of the discipline in his absence, which leads to days where athletics and activities get zero attention.”

Rewarding pursuit

While frustrations can mount, the leaders of school sports programs also tend to be tough self-critics. Somewhere along the line, these folks noticed sacrifices being made by people like them while they were the same age as today’s students. They now carry those lessons forward.

“I had a very positive experience as a three-sport athlete in high school. My coaches all motivated me toward excellence while providing positive lessons and guidance,” said Mohney. “After graduation and upon returning to Michigan after four years of active military duty, my high school football coach offered me a JV football coaching position and strongly suggested that I may have what it takes to be a good teacher and coach. That guidance inspired me.”

Ditto for Gordon.

“When I hired into Royal Oak, there were several people who impacted me as a professional,” Gordon said. “Chuck Jones was our district AD, and he along with Frank Clouser (varsity baseball coach) really made a difference in where I am today. Chuck was always the constant professional who is arguably the most organized and efficient man I have ever met. Frank is the best coach I have ever been around. I have never met a coach who would break down skills and have the unique ability to teach every facet of the game.”

Creating similar moments for countless student-athletes in their hallways is the ultimate goal for today’s athletic directors. Being told they’ve done just that is enough to make all the cafeteria supervision worthwhile.

“The most rewarding part of athletics is when I observe a student who has come from a tough home environment, and through his or her involvement in athletics, they shine,” said Ervin.

“I always love it when graduated student-athletes come back to visit the school,” Mohney said, “so I can meet their children and hear of their successes in life.”

PHOTO: Greenville athletic director Brian Zdanowski points out features of the home lockerroom at Legacy Field, which opened for his school's football teams last fall.

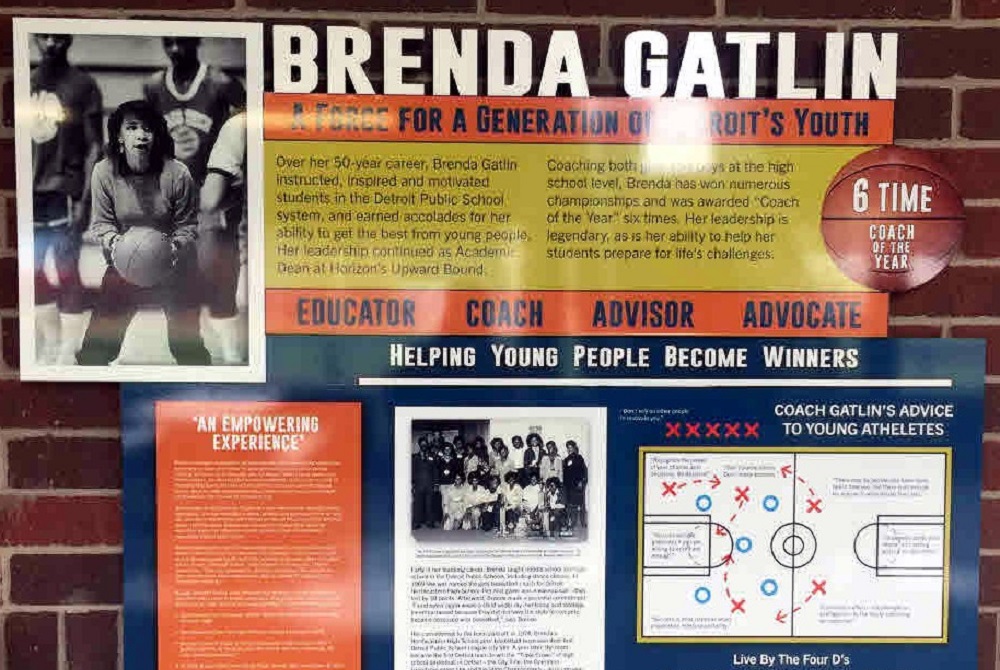

The 6 Ds of Brenda Gatlin - Master of the Coaching Dance

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

September 30, 2021

She is remembered fondly as one of the greatest to ever coach in the Detroit Public School League and the State of Michigan, yet you won’t see Brenda Gatlin’s name among the leaders in all-time basketball victories. A search of the MHSAA List of Girls Basketball Champions displays her name only once.

You will, however, find Gatlin’s name in one most unexpected, yet fitting place.

The Corner Ballpark, the redevelopment of the site of historic Tiger Stadium – located at Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood – includes the Hank Greenberg Walk of Heroes. Opened in 2019, the “exhibit features 12 stories of Michigan citizens who displayed character, innovation and trailblazing spirit in the sports field and the community at large.”

The Corner tribute, as one might expect, includes Tigers greats Greenberg, Hank Aguirre, and Willie Horton. Norman ‘Turkey’ Stearns, a baseball Hall of Fame member and legend with the Detroit Stars of the Negro League is another honoree.

Mixed in with the other eight is Gatlin. The honor is most deserved.

Champion in Life

Gatlin never expected to coach basketball.

“I was a dance teacher,” she told The Southeastern Jungaleer, a public forum for the students and community of Southeastern High School published in the Detroit Free Press in 2009 at the time of her retirement after 43 years in public education. “Early in my teaching career I was asked to coach. I knew nothing about basketball.”

The daughter of a gifted clarinetist, who taught at Lincoln University then left for Virginia State College (VSC) where he became the Head of the Music Department, Gatlin was born in Jefferson City, Mo., to Dr. F Nathaniel Gatlin and his bride, Mildred Pettiford Gatlin, an elementary education teacher and reading specialist. The family moved to Petersburg, Va., when her father accepted a position at VSC. Brenda graduated from segregated Peabody High School – the earliest publicly-funded high school for African Americans in Virginia.

“Dad was strict and no nonsense – mom, nurturing and loving,” Gatlin recently recalled of her parents. “Dad was loving also, but his life was filled with so many trials and tribulations. It would take too much time to explain. He graduated from Oberlin Conservative College of Music, Northwestern University (master’s), and Columbia University (doctorate). Mom graduated from Lincoln University (bachelor’s) and VSC (master’s).

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

Brenda began teaching in Detroit at Barbour Middle School in 1966: “I started my tenure with Detroit Public Schools immediately upon graduating.”

“When I came to Detroit, I only planned to stay here three years. But I fell in love with the city,” she told the Free Press in 1976.

Her next career move was to Detroit Northeastern for the 1969-70 school year.

“I went to the Office of Human Resources and they had an opening at Northeastern high school for a Health and Physical Education and Dance Teacher. All of my classes were dance. I was elated. … My love was always Ballet, and Modern Dance,” she said. “At one of our department meetings, Norm Morris, Department Head, said we need a girls’ basketball coach.”

Both programs were long-established athletic department activities with histories that dated back decades at the school, once located on Detroit’s Lower East Side.

“I was in the midst of creating a choreography for the ALL-City Dance Concert that had been scheduled. Mr. Morris knocked me for a loop and said, Ms. Gatlin, you will coach the girls’ basketball team …” she recalled.

“I never in my wildest dreams ever thought that I would have to coach any sports, especially girls basketball.”

Making of a Coach

As a health and physical education major, Gatlin had played some intramurals and learned about sports mechanics, policies and procedures, and rules and regulations while in college.

“I was familiar with the 6-player rule, but the year I started coaching, the rules for girls had changed from 6-on-6 with a roving player to 5-on-5 with unlimited dribbling” she said. “Well needless to say, I choreographed my plays; I knew about movement. I studied the game as much as possible, but my focus was on dance.

“(I)n our first two seasons, we played only five games (each season),” she said to the Free Press, remembering those days when the girls played only against other Detroit city schools.

“The home team (supplied) oranges at half time, and cookies and milk for a social after the game,” she said recently, describing a completely different era. “You can imagine those girls scrapping and running down the court and then having to sit with the opposing team at the end for a social.”

In 2002, she recalled her opening contest as a coach for Lorne Plant at State Champs: “(Our opponent) proceeded to beat us by about 30 points.”

That game was a turning point.

“When we hosted Central high school, under the coaching jurisdiction of Doris Jones, everything changed. … I greeted Coach Jones. Without a greeting, she immediately said, ‘Where is the gym?’ I knew we were in big trouble.

“Sitting there watching my choreographed plays and movements … watching the determination on the faces of my girls – who looked over to me for answers, which I had none, watching my girls continue to fight and battle, even though they were down by 30 points, changed my life and focus. They just didn’t have the skills to compete. I vowed at that moment, ‘no students under my tutelage would be demoralized or embarrassed because they did not, at least, have the skills to compete.’ That game did it, and I owe it all to Coach Doris Jones. I rolled-up my sleeves and got to work.”

Title IX

The advent of Title IX meant things were changing in girls athletics all over the country.

“I remember attending myriad meetings at Wigle Recreation Center with other Detroit female physical education teachers. (At that time, women were the only ones allowed to coach girls in athletics in Michigan). The purpose of the meeting was to discuss whether girls should adopt the same 10 game schedule as the boys,” she said. “Some of the older coaches, and teachers had comments like: ‘This will be too difficult on the female body … studies show that the female uterus will drop if girls are allowed to run up and down the court for any length of time.’ We had to sit and listen to comments such as that. However, we voted that girls should be provided the same opportunities as boys. I suppose Christine Whitehead, Assistant Director of Athletics, provided Dr. Robert Luby (director of the Department of Health, Physical Education, and Safety for Detroit Public Schools from 1962 to 1983) with our sentiments. With Title IX it was a given. Some people still fought it.”

“Subsequent to the fiasco with Central, I had commenced the process of enhancing my knowledge of the rules and skills inherent in the game of basketball defensively and offensively. I discovered (UCLA coach) John Wooden’s books. His books became sort of my ‘Basketball Bibles.’ I became obsessed with the game. I woke up with basketball, went to sleep with basketball.

“And further, the recreation centers were sending us players who had some experience with the game. The Catholic Schools had a feeder program. We did not. So, my hat goes off to Virginia Lawrence and her sister Evalena, Coach Curtis Green, and many others who taught girls at an early age the skills of basketball.”

With the arrival of the federal law, the MHSAA sponsored its first girls basketball tournament in the fall of 1973. Gatlin’s Falconettes were ready.

Led by Hazel Gibson and the talented Williams sisters (Annette, Helen, and Shelia), they were now among the top teams in Detroit.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

In 1974, Northeastern trounced Murray-Wright, 73-27, winning its first Public School League (PSL) regular-season tournament before 500 fans at Wayne State University’s Matthaei Building. Gatlin’s team again ran into Dominican in the MHSAA Tournament, this time in a District Final. The Williams sisters combined for 61 of the Falconettes’ 71 points but fell 74-71 in a foul-filled game.

The defeat was Northeastern’s only loss in 16 games. Senior Lynn Chadwick posted a career-high 28 points to lead Dominican, which would repeat as Class A champ.

“Girls will play their heart out for you,” Gatlin told the Free Press following the season, “if they believe in you and if you treat them fairly.”

Postseason reward came in 1975 when Northeastern topped Dominican in the MHSAA Semifinals, 75-69, then defeated Farmington Our Lady of Mercy, 67-62, to earn the Class A title. Helen Williams scored 31 in the championship game, while Shelia added 20.

“Everybody knows about Shelia and Helen,” Gatlin told the press, “but it was the defense we got from our guards that did the job for us in the second half. We switched from a zone defense to our press and that made the difference.” Northeastern ended the year with a perfect 20-0 record.

Gatlin spent two more seasons at Northeastern before moving on to newly-opened Detroit Renaissance in the fall of 1978.

College Calls

“In 1978, I was asked to teach in a new examination high school,” continued Gatlin, “Renaissance High School (located at Old Catholic Central School). I hesitated because transferring to Renaissance meant no coaching, for Renaissance would not have an athletic program. It would be strictly academic. I enjoyed the fact that I was a part of the planning process in developing plans for the opening of a new school. The whole Renaissance situation was controversial, because many thought Cass (Tech) was enough. The rest is history. Our students were only able to participate in an intramural program, and I taught dance.”

There, she received a call from the athletic director at University of Michigan-Dearborn. Roy Allen, the associate director of health and education for the Detroit Public Schools, had passed on her name as a possible candidate to lead Michigan-Dearborn’s girls basketball team.

“I was able to juggle my teaching responsibilities at Renaissance with my coaching responsibilities at Michigan-Dearborn,” she said. But balancing the coaching duties would become more challenging as time moved on.

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

Return to the PSL

“In 1981, Dr. Remus, the first principal of Renaissance who convinced me to transfer from Northeastern, was asked to become the principal of Cass Tech. Cass was experiencing some issues that they felt Dr. Remus could clear up,” Gatlin said. “Shirley Burke, the successful girls basketball coach at Cass, was stepping down. Cass also needed a dance teacher. Therefore, Dr. Remus said, ‘Ms. Gatlin, I need you at Cass.’ I think I was ready to get back to the high school level. I learned so much more coaching on the collegiate level and had grown extensively. Coach Burke left me with great players.”

When a teacher’s strike in the fall of 1982 threatened the Lady Technicians’ basketball season, Gatlin and her players petitioned Detroit school superintendent Dr. Arthur Jefferson for equal treatment that was afforded the Detroit PSL prep football teams.

“Coaching staffs at Detroit’s 21 high schools have volunteered to continue the football program after hours despite a three-week-old strike,” wrote Joyce Walker-Tyson in the Free Press. “Schools must play a certain number of games to be eligible for tournaments. While there is no similar requirement for girls’ basketball, Title IX … calls for equality in boys’ and girls’ athletics.

“During the teachers’ strike, (the girls were) the ones who went down to talk to the board (of education) all by themselves,” Gatlin told the Free Press’s Mick McCabe

When all 21 of the girls high school coaches volunteered their services, the girls season was saved, although it started late.

Her 1982 team upset No. 2-ranked Trenton in the Regional Final before advancing to the Class A Quarterfinals and falling to Farmington Mercy 38-34 in a thriller.

The season marked the first of three straight PSL championships won by Gatlin’s teams. At Cass Tech she developed a number of all-city and all-state players, including Pamela Dubose (Iowa/Wayne State), Kendra McDonald (Western Michigan), Nikita Lowry (Ohio State), Adrianne Smiley (Ball State), Clarissa Merritt (Ferris State), Sonya Watkins (Houston) – whose father Tommy had been a running back for the Detroit Lions from 1962-67 – Wendy Mingo, Savarior Moss, Yvette Walters, and others.

Expanded Responsibilities, Greater Influence

In the fall of the 1984-85 school year, Gatlin was asked to also coach Cass Tech’s boys team.

“I looked at my staff and hired the best possible person,” said Jeannette Wheatley, Detroit Cass Tech principal in September 1984. “Brenda is an excellent teacher, and she is a marvelous motivator.”

“I see it as a challenge for all female coaches,” Gatlin said to McCabe after the announcement. “But the men have been doing a dual role for years. The Xs and Os are Xs and Os. Basketball is basketball. Outside the strength factor, it’s the same game.”

Gatlin at Cass Tech, Kathy Curtis at Colon, and Carol Brooks at Burr Oak were all in charge of boys varsity teams that winter. They are believed to be the first to do so in Michigan.

She took the job for a year, but delayed her start. The beginning of the boys schedule in 1984 overlapped the girls postseason. (Prior to the 2007-08 school year, girls basketball was played in the fall in Michigan.) Gatlin didn’t want to shortchange her girls.

The Lady Technicians finished with 22 wins against 4 losses that season, advancing to the Class A Semifinals before falling to eventual champion Flint Northwestern. So it was mid-December before she returned to the boys team for the fourth game of the season, a 60-58 win. A young team, Cass Tech finished 10-9 on the year.

Back in 1974, Gatlin told Hal Schram of the Free Press that she wasn’t sure she wanted to spend the rest of her life coaching basketball.

“You have to be a psychologist, a coach and a sociologist to get the complete job done,” she said.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

In 1992, she moved back to Cass Tech, now as an assistant principal. She became principal at Southeastern in 1999, where she stayed until her retirement.

Determination

Today, she continues to practice her belief in the potential of the human being, working with Cranbrook schools and their Horizons-Upward Bound Program as academic dean. There, she helps students from the Detroit metropolitan area who have limited opportunities to enter and succeed in college.

Her life has always been built around four Ds.

“I still use it even with my students in the Cranbrook Horizons-Upward Bound Program,” she said. “When I use the Ds with Basketball, it becomes five Ds: Determination, Dedication, Desire, Discipline, and Defense.

“My players knew that defense wins games; it’s the name of the game. Offense is for the spectators. Defense is for the win. Our chant in our huddle always ended with, ‘The name of the game?’ They would respond with ‘Defense!’ This would be recited several times in the huddle prior to them taking the floor. My players knew that the most important ‘D’ other than defense is discipline.

“... I may have adopted it from my dad. I also used his quote, ‘The difference between resting on the bench and rusting on the bench is u.’ There were a few others.

“You can be dedicated, you can have the determination and the desire, but if you don’t have the discipline, success may not happen.”

The Sixth ‘D’ - Drive

“I get my determination and drive from my dad. My mom was very mild mannered. They were an awesome couple and a great parental balance for my brother Nat and me,” she said, and that drive – the need to teach – remains strong.

“I can’t stop.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS (Top) Brenda Gatlin is among honorees at Detroit’s “Walk of Heroes” display. (2) Gatlin’s first high school position was at Detroit Northeastern, here in 1971. (3) The 1974 Falconettes pose with their first Public School League trophy. (4) Gatlin huddles with the team in 1976. (5) The 1983 Cass Tech team: (Kneeling, left to right) Kim Justice, Ursula Gordon, Andrea Shaw and LaTrece Owens. (Standing, left to right) Coach Brenda Gatlin, Adrienne Smiley, Clarissa Merritt, Wendy Mingo, Kendra McDonald, Nikita Lowry, Kim Wells and Kathy Scates. (6) Gatlin left Cass Tech in 1986 to become athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch from multiple school yearbooks.)