High School a Time for Plays of All Kinds

April 2, 2015

By Jack Roberts

MHSAA executive director

At end of season or school year banquets attended by student-athletes and their parents, I often tell this short story about my mother that never fails to get a good laugh, especially from mothers:

“At the end of my junior year of high school I attended the graduation ceremony for the senior class on a hot and humid early June evening in our stuffy high school gymnasium. The bleachers on each side were filled to capacity, as were several hundred folding chairs placed on the gymnasium floor.

“The public address system, which was wonderful for announcing at basketball games or wrestling meets, was awful for graduation speeches. Person after person spoke, and the huge audience wondered what they had to say.

“I was present because I was the junior class president; and as part of the ceremony, the senior class president handed me a small shovel. It had something to do with accepting responsibility or carrying on tradition.

“In any event, the senior class president spoke briefly; and then it was my turn. I stepped to the podium, pushed the microphone to the side, and spoke in a voice that was heard and understood in every corner of the gymnasium.

“Whereupon my mother, sitting in one of the folding chairs, positioned right in front of my basketball coach – who had benched me for staying out too late on the night before a game, because I had to attend a required school play rehearsal – my mother turned around, pointed her finger at the coach and said, ‘See there? That’s what he learned at play practice!’

“And she was heard in every corner of the gymnasium too.

“But my mother knew – she just knew – that for me, play practice was as important as basketball practice. And she was absolutely correct.”

This old but true story about in-season demands of school sports actually raises two of the key issues of the debate about out-of-season coaching rules.

One is that we are not talking only about sports. School policies should not only protect and promote opportunities for students to participate in more than one sport; they should also allow for opportunities for students to participate in the non-athletic activities that comprehensive, full-service schools provide.

This is because surveys consistently link student achievement in school as well as success in later life with participation in both the athletic and non-athletic activities of schools. Proper policies permit students time to study, time to practice and play sports and time to be engaged in other school activities that provide opportunities to learn and grow as human beings.

A second issue the story presents is that parents have opinions about what is best for their children. In fact, they feel even more entitled to express those opinions today than my mother did almost 50 years ago. In fact, today, parents believe they are uniquely entitled to make the decisions that affect their children. And often they take the attitude that everyone else should butt out of their business!

The MHSAA knows from direct experience that while school administrators want tighter controls on what coaches and students do out of season, and that most student-athletes and coaches will at least tolerate the imposed limits, parents will be highly and emotionally critical of rules that interfere with how they raise their children.

No matter the cost in time or money to join elite teams, take private lessons, travel to far-away practices and further-away tournaments, no matter how unlikely any of this provides the college athletic scholarship return on investment that parents foolishly pursue, those parents believe they have every right to raise their own children their own way and that it’s not the MHSAA’s business to interfere.

It is for this very reason that MHSAA rules have little to say about what students can and can’t do out of season. Instead, the rules advise member schools and their employees what schools themselves have agreed should be the limits. The rules do this to promote competitive balance. They do this in order to avoid never-ending escalating expense of time and money to keep up on the competitive playing field, court, pool, etc.

Every example we have of organized competitive sports is that, in the absence of limits, some people push the boundaries as far as they can for their advantage, which forces other people to go beyond what they believe is right in order to keep up.

If, during the discussions on out-of-season rules, someone suggests that certain policies be eliminated, thinking people will pause to ask what life would be like without those rules.

Our outcome cannot be mere elimination of regulation, which invites chaos; the objective must be shaping a different future.

A good start would be simpler, more understandable and enforceable rules. A bad ending would be if it forces more student-athletes and school coaches to focus on a single sport year-round.

Process, Relationships Still Matter Most as 4-Time Champ Shillito Coaches 41st Season

By

Steve Vedder

Special for MHSAA.com

October 18, 2024

It was John Shillito's third year as Muskegon Orchard View football coach, and while the wolves weren't exactly knocking at the door, some faint low growls could clearly be heard.

Shillito had been successful at Comstock Park with his teams going 21-8 over three seasons, but the move to Orchard View included 3-6 and 4-5 records the first two.

While there wasn't yet widespread anxiety, Shillito recalls there was a bit of concern.

"I was much younger then and wasn't as successful yet in education," Shillito said. "But we weathered it and came through the other side. But you wonder a little; there's always a little self-doubt. I think it was important to go through it, because you can learn as much even when you're not winning."

Michigan high school football is the better for Shillito sticking it out. Two schools later, Shillito finds himself as the state's third winningest active coach and seventh overall with a 333-106 mark over 41 seasons.

His Zeeland West team is 6-1 this season and likely to become his 27th team – and 15th in a row – to qualify for the playoffs. Shillito's teams at Byron Center, Muskegon Orchard View, East Kentwood and Zeeland West have won a combined 16 conference titles.

Not bad for someone whose first love was baseball. Shillito's father, Harry, played three seasons professionally in the Brooklyn Dodgers system during the "Boys of Summer" era of the 1940s and 50s. Shillito grew up as a talented catcher in the spring and top football prospect as a defensive lineman in football. When programs such as Central Michigan, Eastern Michigan and Northern Michigan began showing an interest, the lure of a football scholarship made it an easy decision which sport he would follow.

After playing three years at Central Michigan, his coaching career kicked off with an assistant gig at Central Bucks East in Pennsylvania in 1980. He became head coach at Comstock Park in 1982.

Shillito said the same motivation which drove him into coaching has kept him in the sport for nearly five decades. It's not necessarily winning state championships – he’s won four at Zeeland West – or fulfilling a deep competitive drive or even the lure of Friday Night Lights in a small community. It's showing up at practices, adhering to a process and building and honing relationships with players and other coaches.

Shillito said the same motivation which drove him into coaching has kept him in the sport for nearly five decades. It's not necessarily winning state championships – he’s won four at Zeeland West – or fulfilling a deep competitive drive or even the lure of Friday Night Lights in a small community. It's showing up at practices, adhering to a process and building and honing relationships with players and other coaches.

Take those away and the 67-year-old Shillito, a member of the Michigan High School Football Coaches Association Hall of Fame, would definitely be looking elsewhere to spend Friday nights in the fall.

"It's the process; I love a good practice. You know when (it's good) and when it isn't. More than even the football, it's the coaching process and the people I work with," he said.

"Winning is a week-to-week deal. This week's game is what we're all about. And then in the offseason, it's preparation for the year coming up. The state titles are always a bonus."

Which isn't to say Shillito isn't competitive. Whether it’s been playing hockey, wiffle ball, 3-on-3 basketball or backyard football with his brothers, Shillito's competitive spirit has thrived.

"Oh yeah," he said. "But I'm a glass half full-type competitor. I can find the positive side in either wins or losses. But for me it's about the preparation, no doubt about it."

Shillito's success has come even with opponents knowing exactly what they'll see offensively from his teams: the famed wing-T offense, which he's run since the mid-1990s and was taught to him by famed West Michigan coach Irv Sigler. In fact, Shillito said if there is anything responsible for his success, it's the ability to implement what he's learned from coaches as a whole such as Mike Henry, the longtime basketball coach at Orchard View, or former Remus Chippewa Hills football coach Ron Reardon.

When he first got into coaching, Shillito said the wing-T seemed the easiest to teach. He's tweaked the process over the years, but it's been highly successful for him wherever he's coached. The number of Michigan teams which run the wing-T has probably lessened over the years as passing has taken over many high school offenses. But Shillito said the run-first philosophy can still be found in pockets all over the state. Shillito said he has no second thoughts about devoting his offense to the wing-T, and the success only underscores the point.

"It can be difficult if you're not winning, no doubt about it," said Shillito, who figures he's coached about three dozen 1,000-yard rushers. "But the value in the system is that it's an easier process. That is, if you get a buy-in from the players and community. We've had that at Zeeland West."

As the sun begins to set on Shillito's coaching career, he's hard-pressed to pick his best, favorite or most surprising teams. For starters, there's the 1983 Byron Center team which reached the Class C Semifinals, or the 1995 and 1999 Orchard View teams which played in Class B Finals and combined for a 24-3 mark.

As the sun begins to set on Shillito's coaching career, he's hard-pressed to pick his best, favorite or most surprising teams. For starters, there's the 1983 Byron Center team which reached the Class C Semifinals, or the 1995 and 1999 Orchard View teams which played in Class B Finals and combined for a 24-3 mark.

Or maybe the 13-1 Division 1 runner-up club at East Kentwood in 2002, and the 2006 Zeeland West team which claimed the Division 4 title after winning its last 11 games by an average of 35 points per. Or the 2011 Zeeland West team which went 14-0 to kick off a phenomenal five-year stretch during which the Dux went a combined 60-6.

Ask Shillito about any of those seasons, and his answer as to what he remembers most about his coaching career may be surprising. Many of his most cherished moments include his teams going just 5-6 over the years against Muskegon, including three playoff losses that ended the Dux's season. Balance that with his record against other programs, such as a 73-16 mark against other Lakeshore teams, including an 18-7 record against rival Zeeland East. Or a 10-4 record against traditional Grand Rapids-area powers such as Lowell, Grand Rapids Catholic Central, South Christian, West Catholic and Hudsonville. In the postseason, Shillito's teams are an amazing 54-22 over 26 seasons in the MHSAA Playoffs.

As for knocking heads with Muskegon, Shillito said the thrill of a great rivalry and the consistency his teams have shown over the years is what has always driven him.

"It's the longevity and consistency," Shillito said. "I've gotten to work with great people who have had an equal share in this. I've had such a wide variety of guys I've worked with in four programs, and it’s meaningful. "

He is coy on when he might finally call it a career. He could wake up tomorrow and decide it's the time, or it could be next week, the end of the season or maybe one more season. Who's to say?

"We're getting close now," he will say. "We're always in the moment; that's just where we are. Then we'll evaluate things after the season. That's been true now for several seasons."

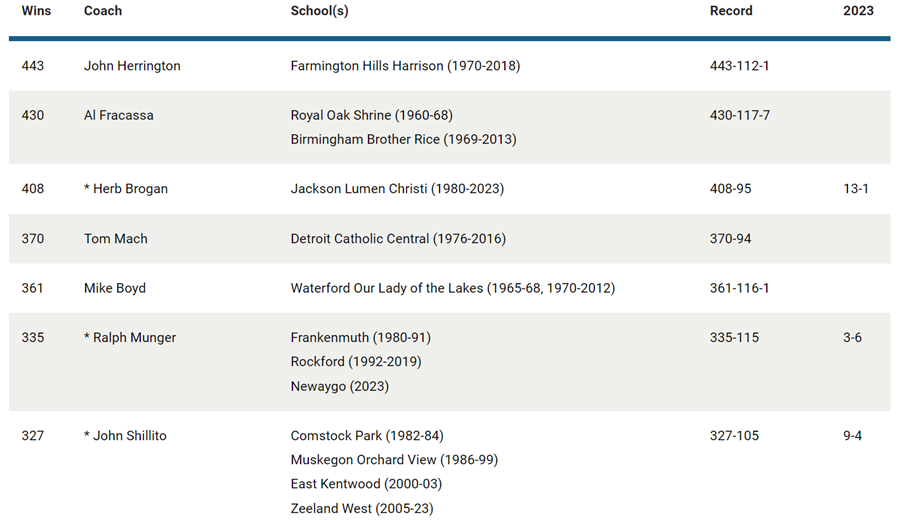

PHOTOS (Top) Zeeland West football coach John Shillito, right, receives the Division 4 championship trophy from MHSAA Representative Council member Orlando Medina in 2015 at Ford Field. (Middle) Entering this season, Shillito ranked seventh all-time and third among active coaches for football victories in the MHSAA record book. (Below) Shillito prepares to send in one of his East Kentwood players during the 2002 Division 1 Final at Pontiac Silverdome. (MHSAA file photos.)