CPR Training, CAP Add to Preparedness

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

October 12, 2015

A recent graduate from Ovid-Elsie High School named Chris Fowler started classes this fall at Michigan State University, his days representing the Marauders on the basketball court, football field and golf course now memories as he starts the next chapter of his young adult life.

But his story also will remain a reminder as his high school’s athletic department prepares each year to keep its athletes as safe as possible.

Three years ago next month, Fowler collapsed on the football practice field in cardiac arrest. The then-sophomore was brought back to life by two of his coaches, who revived him with CPR and an AED machine.

There’s no need for athletic director Soni Latz to recount the events of that day when explaining the importance of being ready to respond to a medical crisis – her coaches are well aware of why Fowler survived and understand completely why they too must be prepared.

“Everyone is very aware of what happened and the importance of being trained and knowing what to do, and actually feeling comfortable to step in and administer CPR when needed,” Latz said. “You can feel it’s never going to happen to you, but once it has, it makes you more aware and conscientious to be prepared.”

But Fowler’s story is worth noting on a larger level as varsity coaches at all MHSAA member schools are required this year for the first time to become certified in CPR, and as the largest classes in Coaches Advancement Program history begin course work that includes up to four modules designed to make them aware of health and safety situations that may arise at their schools as well.

The CPR requirement is the most recent addition to an MHSAA thrust toward raising expectations for coaches’ preparedness. The first action of this effort required all assistant and subvarsity coaches at the high school level to complete the same rules and risk minimization meeting requirement as high school varsity head coaches beginning with the 2014-15 school year.

The next action, following the CPR mandate, will require all persons hired as a high school varsity head coach for the first time at an MHSAA member school after July 31, 2016, to have completed the MHSAA’s Coaches Advancement Program Level 1 or Level 2.

In addition, MHSAA member schools this summer received the “Anyone can Save a Life” program, an emergency action plan curriculum designed by the Minnesota State High School League to help teams – guided by their coaches – create procedures for working together during medical emergencies.

“Coaches get asked to do a lot, and even if a school has an athletic trainer or some other health care professional, that person can’t be everywhere all the time. Coaches often are called upon to be prepared for (medical) situations,” said Gayle Thompson, an adjunct assistant professor at Albion College who formerly directed the athletic training program at Western Michigan University and continues to teach CAP sports medicine modules.

“The more (coaches) can learn to handle the situations that can inevitably arise, the better off they’re going to feel in those situations and the better care they’ll be able to offer their athletes. It’s proven that the faster athletes are able to get care, the quicker they’re able to come back to play.”

Pontiac Notre Dame Prep – which has sent a number of coaches through the CAP program – began a focus on heart safety about five years ago after a student-athlete was diagnosed with a heart issue that allowed her to continue to play volleyball and softball, but not basketball. Athletic director Betty Wroubel said that prior to the student’s diagnosis, the school did provide training in CPR, AED use and artificial respiration; however, that situation put coaches and administrators further on the alert.

Pontiac Notre Dame Prep – which has sent a number of coaches through the CAP program – began a focus on heart safety about five years ago after a student-athlete was diagnosed with a heart issue that allowed her to continue to play volleyball and softball, but not basketball. Athletic director Betty Wroubel said that prior to the student’s diagnosis, the school did provide training in CPR, AED use and artificial respiration; however, that situation put coaches and administrators further on the alert.

Her school offers CPR training also to subvarsity and middle school coaches, using a combination of video instruction from the American Red Cross and in-person guidance by members of the school community who are certified to teach those skills. Students at the school also have received training – and it paid off a few years ago when one of them gave CPR to a baby who had stopped breathing at a local shopping mall.

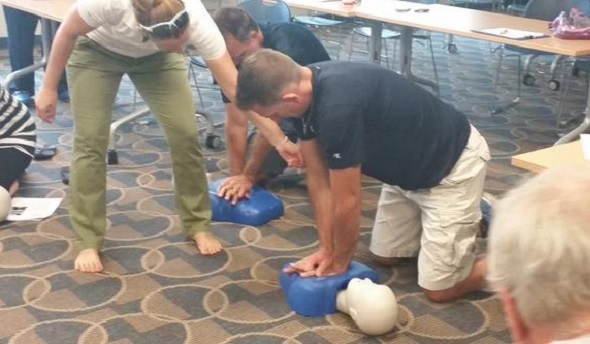

Portage Central scheduled two sessions this fall for its coaches to receive not only CPR certification, but AED training as well. Central was fortunate to have an American Red Cross first-aid trainer in house, teacher Rachel Flachs, who also is close to the athletic side as the girls swimming and diving coach at Mattawan High School.

Central athletic director Joe Wallace said the training was offered not just to varsity head coaches, but every head coach on every level of the program so that “at least we know that at every given practice, every game, we’d have someone recently trained,” he said.

And he was proud of how his coaches immersed themselves in the subject matter.

“They were putting themselves in scenarios to see how it related to their own sports and asking really great questions,” Wallace said. “It was thought provoking.”

The CAP sports medicine modules are designed to do the same as coaches consider the medical situations they could face. They aren’t designed as “medical training,” said Tony Moreno, a professor of kinesiology at Eastern Michigan University and teacher of all four CAP sports medicine modules. Rather, attendees receive an awareness and basic education on common injuries, injury mechanisms and prevention, and how to create an action plan in the event of an injury incident.

The CAP program touches on a variety of safety topics in several of the available seven levels of coach education.

CAP 1 – which is part of the mandate for new coaches beginning next school year – includes “Sports Medicine and First Aid.” Cap 4 has modules titled “Understanding Athlete Development” and “Strength and Conditioning: Designing Your Program.” CAP 5 includes the session, “Peak Health and Performance.” Attendees also have the option of receiving CPR and AED training as an addition to some courses.

With a quick Internet search, coaches have no trouble finding a variety of resources on sports medicine, performance enhancement, nutrition and healthy living regarding young athletes. “However, some of these sources are more credible and scientifically-based in comparison to others,” Moreno said. “CAP strives on an annual basis to continue to update and improve the quality and credibility of this information and in a face-to-face manner where coaches have the opportunity to ask questions about their experiences and specific programs.”

“Having the CAP requirement will only make them better informed. Many have had this kind of information before, but there’s always something new coming,” Thompson added. “I think we do a good job, not of trying to tell them they were wrong, but maybe taking what they’ve known a step further and making them better prepared – empowering them to do their best.”

Wroubel may understand more than most athletic directors the growing list of tasks coaches are asked to accomplish; she’s also one of the winningest volleyball and softball coaches in MHSAA history and continues to guide both Fighting Irish programs.

But she and Wallace both said the CPR mandate isn’t considered another box to check on a to-do list; there’s enthusiasm because of its importance and the opportunity to carry those skills into other areas of community life as well.

Wroubel has served as a coach since 1975 and said this renewed emphasis on coaches having knowledge of sports medicine actually is a return to how things were when she started. Back then, coaches were responsible for being that first line of medical know-how, from taping ankles to providing ice and evaluating when their athletes should make a trip to the doctor’s office.

“When I first started coaching, we didn’t have sports medicine people, trainers, or team doctors other than for football. You did everything yourself,” Wroubel said. “I think everybody got away from that, but I think it’s coming back because a trainer can’t be everywhere.

“It’s healthy and it’s good for kids. … The more of us with emergency skills, the better we’re able to serve our community.”

PHOTOS: (Top) Portage Central coaches receive CPR training earlier this fall. (Middle) Pontiac Notre Dame Prep coaches practice during AED training. (Photos courtesy of school athletic departments.)

The 6 Ds of Brenda Gatlin - Master of the Coaching Dance

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

September 30, 2021

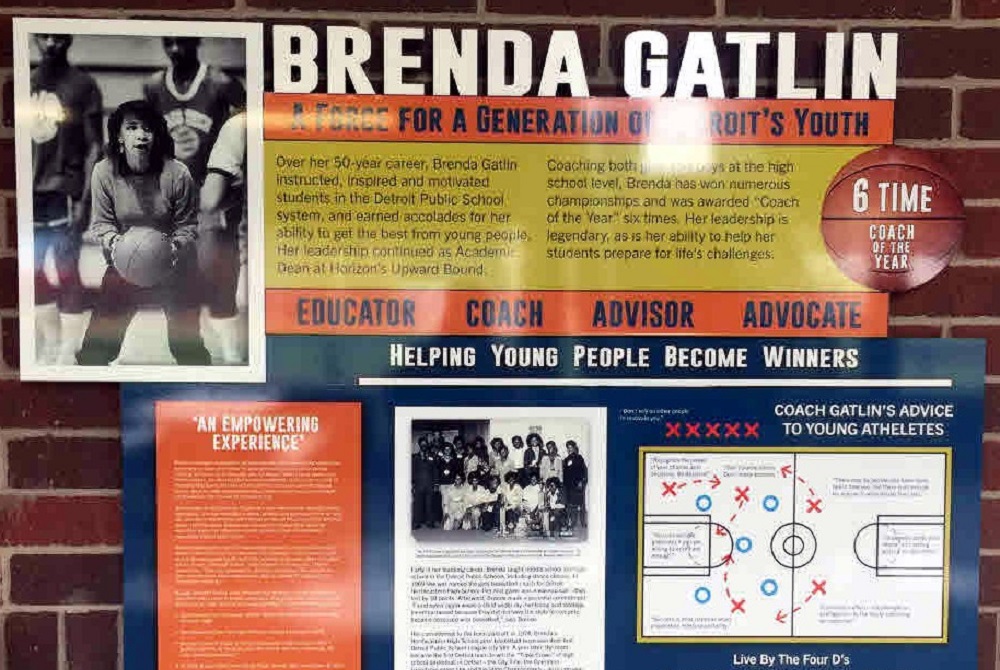

She is remembered fondly as one of the greatest to ever coach in the Detroit Public School League and the State of Michigan, yet you won’t see Brenda Gatlin’s name among the leaders in all-time basketball victories. A search of the MHSAA List of Girls Basketball Champions displays her name only once.

You will, however, find Gatlin’s name in one most unexpected, yet fitting place.

The Corner Ballpark, the redevelopment of the site of historic Tiger Stadium – located at Michigan and Trumbull in Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood – includes the Hank Greenberg Walk of Heroes. Opened in 2019, the “exhibit features 12 stories of Michigan citizens who displayed character, innovation and trailblazing spirit in the sports field and the community at large.”

The Corner tribute, as one might expect, includes Tigers greats Greenberg, Hank Aguirre, and Willie Horton. Norman ‘Turkey’ Stearns, a baseball Hall of Fame member and legend with the Detroit Stars of the Negro League is another honoree.

Mixed in with the other eight is Gatlin. The honor is most deserved.

Champion in Life

Gatlin never expected to coach basketball.

“I was a dance teacher,” she told The Southeastern Jungaleer, a public forum for the students and community of Southeastern High School published in the Detroit Free Press in 2009 at the time of her retirement after 43 years in public education. “Early in my teaching career I was asked to coach. I knew nothing about basketball.”

The daughter of a gifted clarinetist, who taught at Lincoln University then left for Virginia State College (VSC) where he became the Head of the Music Department, Gatlin was born in Jefferson City, Mo., to Dr. F Nathaniel Gatlin and his bride, Mildred Pettiford Gatlin, an elementary education teacher and reading specialist. The family moved to Petersburg, Va., when her father accepted a position at VSC. Brenda graduated from segregated Peabody High School – the earliest publicly-funded high school for African Americans in Virginia.

“Dad was strict and no nonsense – mom, nurturing and loving,” Gatlin recently recalled of her parents. “Dad was loving also, but his life was filled with so many trials and tribulations. It would take too much time to explain. He graduated from Oberlin Conservative College of Music, Northwestern University (master’s), and Columbia University (doctorate). Mom graduated from Lincoln University (bachelor’s) and VSC (master’s).

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

“I, of course, did not want to attend Virginia State because I grew up on the campus. My dad insisted, ‘If it is good enough for me to work here, it is good enough for you to attend.’ I started out as an English major my freshman year and changed to health and physical education with a focus on dance. They did not have a choice of dance as a major.”

Brenda began teaching in Detroit at Barbour Middle School in 1966: “I started my tenure with Detroit Public Schools immediately upon graduating.”

“When I came to Detroit, I only planned to stay here three years. But I fell in love with the city,” she told the Free Press in 1976.

Her next career move was to Detroit Northeastern for the 1969-70 school year.

“I went to the Office of Human Resources and they had an opening at Northeastern high school for a Health and Physical Education and Dance Teacher. All of my classes were dance. I was elated. … My love was always Ballet, and Modern Dance,” she said. “At one of our department meetings, Norm Morris, Department Head, said we need a girls’ basketball coach.”

Both programs were long-established athletic department activities with histories that dated back decades at the school, once located on Detroit’s Lower East Side.

“I was in the midst of creating a choreography for the ALL-City Dance Concert that had been scheduled. Mr. Morris knocked me for a loop and said, Ms. Gatlin, you will coach the girls’ basketball team …” she recalled.

“I never in my wildest dreams ever thought that I would have to coach any sports, especially girls basketball.”

Making of a Coach

As a health and physical education major, Gatlin had played some intramurals and learned about sports mechanics, policies and procedures, and rules and regulations while in college.

“I was familiar with the 6-player rule, but the year I started coaching, the rules for girls had changed from 6-on-6 with a roving player to 5-on-5 with unlimited dribbling” she said. “Well needless to say, I choreographed my plays; I knew about movement. I studied the game as much as possible, but my focus was on dance.

“(I)n our first two seasons, we played only five games (each season),” she said to the Free Press, remembering those days when the girls played only against other Detroit city schools.

“The home team (supplied) oranges at half time, and cookies and milk for a social after the game,” she said recently, describing a completely different era. “You can imagine those girls scrapping and running down the court and then having to sit with the opposing team at the end for a social.”

In 2002, she recalled her opening contest as a coach for Lorne Plant at State Champs: “(Our opponent) proceeded to beat us by about 30 points.”

That game was a turning point.

“When we hosted Central high school, under the coaching jurisdiction of Doris Jones, everything changed. … I greeted Coach Jones. Without a greeting, she immediately said, ‘Where is the gym?’ I knew we were in big trouble.

“Sitting there watching my choreographed plays and movements … watching the determination on the faces of my girls – who looked over to me for answers, which I had none, watching my girls continue to fight and battle, even though they were down by 30 points, changed my life and focus. They just didn’t have the skills to compete. I vowed at that moment, ‘no students under my tutelage would be demoralized or embarrassed because they did not, at least, have the skills to compete.’ That game did it, and I owe it all to Coach Doris Jones. I rolled-up my sleeves and got to work.”

Title IX

The advent of Title IX meant things were changing in girls athletics all over the country.

“I remember attending myriad meetings at Wigle Recreation Center with other Detroit female physical education teachers. (At that time, women were the only ones allowed to coach girls in athletics in Michigan). The purpose of the meeting was to discuss whether girls should adopt the same 10 game schedule as the boys,” she said. “Some of the older coaches, and teachers had comments like: ‘This will be too difficult on the female body … studies show that the female uterus will drop if girls are allowed to run up and down the court for any length of time.’ We had to sit and listen to comments such as that. However, we voted that girls should be provided the same opportunities as boys. I suppose Christine Whitehead, Assistant Director of Athletics, provided Dr. Robert Luby (director of the Department of Health, Physical Education, and Safety for Detroit Public Schools from 1962 to 1983) with our sentiments. With Title IX it was a given. Some people still fought it.”

“Subsequent to the fiasco with Central, I had commenced the process of enhancing my knowledge of the rules and skills inherent in the game of basketball defensively and offensively. I discovered (UCLA coach) John Wooden’s books. His books became sort of my ‘Basketball Bibles.’ I became obsessed with the game. I woke up with basketball, went to sleep with basketball.

“And further, the recreation centers were sending us players who had some experience with the game. The Catholic Schools had a feeder program. We did not. So, my hat goes off to Virginia Lawrence and her sister Evalena, Coach Curtis Green, and many others who taught girls at an early age the skills of basketball.”

With the arrival of the federal law, the MHSAA sponsored its first girls basketball tournament in the fall of 1973. Gatlin’s Falconettes were ready.

Led by Hazel Gibson and the talented Williams sisters (Annette, Helen, and Shelia), they were now among the top teams in Detroit.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

The team advanced to the Class A Regional Finals, falling to eventual state champ Detroit Dominican. All-city selection Sheila Williams, a sophomore, scored 26 points and pulled down 26 rebounds to lead the Falconettes.

In 1974, Northeastern trounced Murray-Wright, 73-27, winning its first Public School League (PSL) regular-season tournament before 500 fans at Wayne State University’s Matthaei Building. Gatlin’s team again ran into Dominican in the MHSAA Tournament, this time in a District Final. The Williams sisters combined for 61 of the Falconettes’ 71 points but fell 74-71 in a foul-filled game.

The defeat was Northeastern’s only loss in 16 games. Senior Lynn Chadwick posted a career-high 28 points to lead Dominican, which would repeat as Class A champ.

“Girls will play their heart out for you,” Gatlin told the Free Press following the season, “if they believe in you and if you treat them fairly.”

Postseason reward came in 1975 when Northeastern topped Dominican in the MHSAA Semifinals, 75-69, then defeated Farmington Our Lady of Mercy, 67-62, to earn the Class A title. Helen Williams scored 31 in the championship game, while Shelia added 20.

“Everybody knows about Shelia and Helen,” Gatlin told the press, “but it was the defense we got from our guards that did the job for us in the second half. We switched from a zone defense to our press and that made the difference.” Northeastern ended the year with a perfect 20-0 record.

Gatlin spent two more seasons at Northeastern before moving on to newly-opened Detroit Renaissance in the fall of 1978.

College Calls

“In 1978, I was asked to teach in a new examination high school,” continued Gatlin, “Renaissance High School (located at Old Catholic Central School). I hesitated because transferring to Renaissance meant no coaching, for Renaissance would not have an athletic program. It would be strictly academic. I enjoyed the fact that I was a part of the planning process in developing plans for the opening of a new school. The whole Renaissance situation was controversial, because many thought Cass (Tech) was enough. The rest is history. Our students were only able to participate in an intramural program, and I taught dance.”

There, she received a call from the athletic director at University of Michigan-Dearborn. Roy Allen, the associate director of health and education for the Detroit Public Schools, had passed on her name as a possible candidate to lead Michigan-Dearborn’s girls basketball team.

“I was able to juggle my teaching responsibilities at Renaissance with my coaching responsibilities at Michigan-Dearborn,” she said. But balancing the coaching duties would become more challenging as time moved on.

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

“It became even more difficult as the distances of scheduled games became further and further. We were only provided a van that my Assistant Coach and I had to drive. Returning so late and trying not to short-change my students at Renaissance became even more difficult.”

Return to the PSL

“In 1981, Dr. Remus, the first principal of Renaissance who convinced me to transfer from Northeastern, was asked to become the principal of Cass Tech. Cass was experiencing some issues that they felt Dr. Remus could clear up,” Gatlin said. “Shirley Burke, the successful girls basketball coach at Cass, was stepping down. Cass also needed a dance teacher. Therefore, Dr. Remus said, ‘Ms. Gatlin, I need you at Cass.’ I think I was ready to get back to the high school level. I learned so much more coaching on the collegiate level and had grown extensively. Coach Burke left me with great players.”

When a teacher’s strike in the fall of 1982 threatened the Lady Technicians’ basketball season, Gatlin and her players petitioned Detroit school superintendent Dr. Arthur Jefferson for equal treatment that was afforded the Detroit PSL prep football teams.

“Coaching staffs at Detroit’s 21 high schools have volunteered to continue the football program after hours despite a three-week-old strike,” wrote Joyce Walker-Tyson in the Free Press. “Schools must play a certain number of games to be eligible for tournaments. While there is no similar requirement for girls’ basketball, Title IX … calls for equality in boys’ and girls’ athletics.

“During the teachers’ strike, (the girls were) the ones who went down to talk to the board (of education) all by themselves,” Gatlin told the Free Press’s Mick McCabe

When all 21 of the girls high school coaches volunteered their services, the girls season was saved, although it started late.

Her 1982 team upset No. 2-ranked Trenton in the Regional Final before advancing to the Class A Quarterfinals and falling to Farmington Mercy 38-34 in a thriller.

The season marked the first of three straight PSL championships won by Gatlin’s teams. At Cass Tech she developed a number of all-city and all-state players, including Pamela Dubose (Iowa/Wayne State), Kendra McDonald (Western Michigan), Nikita Lowry (Ohio State), Adrianne Smiley (Ball State), Clarissa Merritt (Ferris State), Sonya Watkins (Houston) – whose father Tommy had been a running back for the Detroit Lions from 1962-67 – Wendy Mingo, Savarior Moss, Yvette Walters, and others.

Expanded Responsibilities, Greater Influence

In the fall of the 1984-85 school year, Gatlin was asked to also coach Cass Tech’s boys team.

“I looked at my staff and hired the best possible person,” said Jeannette Wheatley, Detroit Cass Tech principal in September 1984. “Brenda is an excellent teacher, and she is a marvelous motivator.”

“I see it as a challenge for all female coaches,” Gatlin said to McCabe after the announcement. “But the men have been doing a dual role for years. The Xs and Os are Xs and Os. Basketball is basketball. Outside the strength factor, it’s the same game.”

Gatlin at Cass Tech, Kathy Curtis at Colon, and Carol Brooks at Burr Oak were all in charge of boys varsity teams that winter. They are believed to be the first to do so in Michigan.

She took the job for a year, but delayed her start. The beginning of the boys schedule in 1984 overlapped the girls postseason. (Prior to the 2007-08 school year, girls basketball was played in the fall in Michigan.) Gatlin didn’t want to shortchange her girls.

The Lady Technicians finished with 22 wins against 4 losses that season, advancing to the Class A Semifinals before falling to eventual champion Flint Northwestern. So it was mid-December before she returned to the boys team for the fourth game of the season, a 60-58 win. A young team, Cass Tech finished 10-9 on the year.

Back in 1974, Gatlin told Hal Schram of the Free Press that she wasn’t sure she wanted to spend the rest of her life coaching basketball.

“You have to be a psychologist, a coach and a sociologist to get the complete job done,” she said.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

She continued coaching the girls at Cass Tech in the fall of 1985. Then an opportunity came in 1986 to move into administration and serve as athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. She took the job, as it offered an opportunity to make impact on a larger scale. There, she also taught modern dance.

In 1992, she moved back to Cass Tech, now as an assistant principal. She became principal at Southeastern in 1999, where she stayed until her retirement.

Determination

Today, she continues to practice her belief in the potential of the human being, working with Cranbrook schools and their Horizons-Upward Bound Program as academic dean. There, she helps students from the Detroit metropolitan area who have limited opportunities to enter and succeed in college.

Her life has always been built around four Ds.

“I still use it even with my students in the Cranbrook Horizons-Upward Bound Program,” she said. “When I use the Ds with Basketball, it becomes five Ds: Determination, Dedication, Desire, Discipline, and Defense.

“My players knew that defense wins games; it’s the name of the game. Offense is for the spectators. Defense is for the win. Our chant in our huddle always ended with, ‘The name of the game?’ They would respond with ‘Defense!’ This would be recited several times in the huddle prior to them taking the floor. My players knew that the most important ‘D’ other than defense is discipline.

“... I may have adopted it from my dad. I also used his quote, ‘The difference between resting on the bench and rusting on the bench is u.’ There were a few others.

“You can be dedicated, you can have the determination and the desire, but if you don’t have the discipline, success may not happen.”

The Sixth ‘D’ - Drive

“I get my determination and drive from my dad. My mom was very mild mannered. They were an awesome couple and a great parental balance for my brother Nat and me,” she said, and that drive – the need to teach – remains strong.

“I can’t stop.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS (Top) Brenda Gatlin is among honorees at Detroit’s “Walk of Heroes” display. (2) Gatlin’s first high school position was at Detroit Northeastern, here in 1971. (3) The 1974 Falconettes pose with their first Public School League trophy. (4) Gatlin huddles with the team in 1976. (5) The 1983 Cass Tech team: (Kneeling, left to right) Kim Justice, Ursula Gordon, Andrea Shaw and LaTrece Owens. (Standing, left to right) Coach Brenda Gatlin, Adrienne Smiley, Clarissa Merritt, Wendy Mingo, Kendra McDonald, Nikita Lowry, Kim Wells and Kathy Scates. (6) Gatlin left Cass Tech in 1986 to become athletic director at Detroit Southwestern. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch from multiple school yearbooks.)