Old 5-A League Fueled Wrestling's Rise

June 29, 2020

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

This latest quest into wrestling began with an inquiry, as these projects often do.

My work with the MHSAA – which includes the title ‘historian’ – is mostly a hobby that began many years ago. The diversion often gets me into press boxes and places the average sports fan doesn’t usually get to venture. Now and then, I get to talk into a microphone. But mostly, it is hours of digging; pouring through scrapbooks, yearbooks and newspapers, old and new, as I search for names, details and stories lost in time. The pursuit sometimes leads to awkward phone calls, e-mails and messages where I try to describe who I am and why I’m chasing a phone number for someone, a person’s mother or father, grandmother or grandfather.

I adore the chase and resolving mysteries. I love visiting libraries and schools and delight in connecting with people. I love filling in holes and connecting dots. I’m a computer guy by trade, focused on analyzing and aligning data. I equate sports searches to detective work, and for fans of old television, I’m like Columbo without the trench coat or cigar, always asking, “Just one more thing …”

Wrestling

My first visit to the sport was in junior high gym class. That’s when Coach Murphy paired me up against another undersized classmate. With the shrill of a whistle, we battled it out on a deep red colored mat – representative of one half of the red and grey school colors of Nelson Junior High. The struggle lasted for no more than a matter of seconds. With a slap of a mat, or perhaps another whistle, it was over. I lost by ‘fall’ – the gentler way of saying I was pinned.

My second visit to the sport came in high school. That’s when the wrestling coach stopped me in the hall one day to suggest I join the wrestling team. Apparently, word of the skills I demonstrated at Nelson hadn’t travelled the half mile east from the junior high to the high school. Quickly recognizing this fact, I told him it might be counter-productive, as I wasn’t much of a wrestler. He was undeterred. Because I was still undersized, he said, I would likely win a fair number of matches. Many schools, it seemed, struggled to find someone to wrestle in the lower classes, and hence, would have to forfeit. I still turned him down.

My second visit to the sport came in high school. That’s when the wrestling coach stopped me in the hall one day to suggest I join the wrestling team. Apparently, word of the skills I demonstrated at Nelson hadn’t travelled the half mile east from the junior high to the high school. Quickly recognizing this fact, I told him it might be counter-productive, as I wasn’t much of a wrestler. He was undeterred. Because I was still undersized, he said, I would likely win a fair number of matches. Many schools, it seemed, struggled to find someone to wrestle in the lower classes, and hence, would have to forfeit. I still turned him down.

I give credit to the Coach Erickson. He was trying to involve a kid in athletics that wasn’t going to make the football, basketball or track team. But that bit of wisdom didn’t hit me until long after high school.

As the above may demonstrate, an extensive understanding of the intricate particulars of wrestling isn’t my strong suit. I’ve attended only one MHSAA Wrestling Final. That visit still remains among my favorite sports sights. The pageantry of the Grand March staged before the orchestrated pandemonium of the MHSAA wrestling championship combined with huge crowds and inspiring athleticism creates a spectacular event.

The Latest Project

Recently, a question, relating to past individual champions from the earliest days of the championships, arrived at the MHSAA office. The Association has awarded wrestling titles since 1948, and a list of team champions and runners-up from the beginning to the present appear on the MHSAA Website. Missing, however, are the names of the individuals who won championships between 1948 and 1960.

To find an answer, that meant a deep dive into newspapers, yearbooks and old wrestling guides to exhume the particulars from articles and agate, cross-referencing results, matching last names to first names, correcting spellings and occasionally schools when obvious errors have been made.

Technology has helped carve away some time and travel when embarking on such a project. Once, the only way to dig out such information was to travel to microfilm, and then spend hours scrolling past print. Today, thanks to some online archives, even during a global pandemic, we can visit a handful of Michigan newspapers via the internet. Tack on the ability to search the online cloud of information, intriguing elements intermittently bubble to the surface, transforming a standing list of names and schools to an account that brings at least some names to life.

The Beginnings

An initial look at the existing team championship listings revealed the first fact. For all intents and purposes, the earliest days of the MHSAA wrestling state championships served as a glorified meet for the members of the 5-A Conference. The league, comprised of Ann Arbor, Battle Creek Central, Jackson, Lansing Eastern and Lansing Sexton high schools, was where wrestling as a prep sport first gained traction in Michigan. Almost immediately, Greater Lansing established a stronghold on the sport that would last those first 13 years.

From 1948 to 1960, there was only one classification in which all schools, regardless of size, competed. In 10 of those 13 years, one of two Lansing high schools – Eastern or Sexton – won the state’s mat championship. In the three years when a Lansing team didn’t win, they finished as runner-up. Those three were part seven total of that baker’s dozen when either Eastern or Sexton finished second.

Growth in Michigan

The first championship tournament in 1948 involved around a dozen schools. While expansion into other schools commenced slowly, by 1957, wrestling had progressed into the fastest growing sport in Michigan.

“The sport blossoms into many new schools every year,” stated George Maskin in a January issue of the Detroit Times in 1957. “Best estimates are that at least 60 varsity prep teams now are in competition. The figure should come close to the 100 mark within a year or two. Prep wrestling has grown with such swiftness it now is necessary to hold regionals to determine qualifiers for the state meet.

“It is not the kind of wrestling one has watched on television or in some of the professional arenas around the state,” he added, trying to educate the public about the difference between the prep sport and the form of broadcast entertainment then popular. “Groans and grunts have no part in high school wrestling … nor does hair pulling or stamping the feet … or pointing a finger into the referee’s eye.”

Coaches of wrestling noted that it was one of the few sports offered that gave equal opportunity to students regardless of their physical build. Separated into 12 weight classifications, running from 95 pounds and under up to the unlimited, or heavyweight division, there was a place for all.

Coaches of wrestling noted that it was one of the few sports offered that gave equal opportunity to students regardless of their physical build. Separated into 12 weight classifications, running from 95 pounds and under up to the unlimited, or heavyweight division, there was a place for all.

“Take the kid who weighs 95 pounds,” Ignatius ‘Iggy’ Konrad, a former wrestler at Michigan State and the coach at Lansing Sexton, told Maskin. “He’ll participate against a boy of similar weight. Thus a kid whose athletic possibilities might appear hopeless (in other sports) finds a place for himself in wrestling.”

As the sport continued to expand, coaches were still trying to explain the worth.

“Parents should try to understand the difference between television wrestling and high school and college wrestling,” Grandville coach Kay Hutsell told a Grand Rapids Press reporter in December 1960. “There is no comparison. TV is 100 percent acting.”

A state champion wrestler as a high school student in Illinois, where spectator interest and participation was far greater than in those early days of wrestling in Michigan, Hutsell twice lettered in the sport at Indiana University.

“Wrestling is a conditioner and perhaps develops the body better than any other sport. About the only way wrestling can educate the adults (in the western Michigan area about the sport) is through newspapers.” He felt people should come to “see for themselves.”

The Tournament

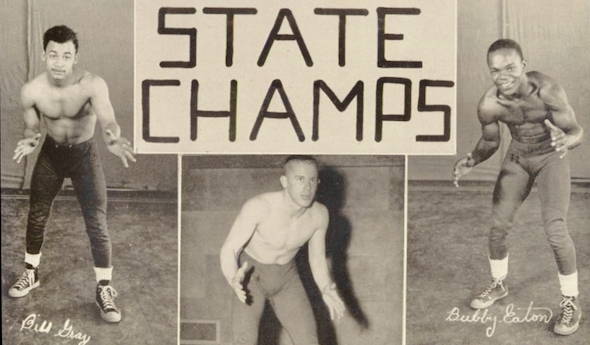

Lansing Sexton won the state’s inaugural team wrestling title, 54-43 over the Ann Arbor Pioneers, with the event run off on the mats of the University of Michigan in 1948. Both Floyd Eaton at 127 pounds and Carl Covert at 133 ended the year undefeated for the Big Reds. Five wrestlers from each school earned individual titles that first year. Jackson’s heavyweight, Norm Blank, scored a pin over Sexton’s Dick Buckmaster. The pair had split their two previous matches during league competition.

Ann Arbor grabbed the next two MHSAA team titles, both by a mere four points, first 60-56 over Sexton, then topping the Quakers of Lansing Eastern, 56-52, in 1950.

Ann Arbor grabbed the next two MHSAA team titles, both by a mere four points, first 60-56 over Sexton, then topping the Quakers of Lansing Eastern, 56-52, in 1950.

Eight wrestlers qualified for the final round for both Ann Arbor and Sexton in 1949, with five each earning championships. Both schools had three wrestlers finish in third and fourth place; hence the team title was awarded based on Ann Arbor tallying more pins. A total of 96 wrestlers from 11 schools participated in the tournament. Ted Lennox, wrestling at 95 pounds, became the first athlete from the Michigan School for the Blind to compete for an individual title but was defeated by Sexton’s Leo Kosloski. Lennox would later wrestle for Michigan State.

In 1950, nine Ann Arbor wrestlers advanced to the final round with six seizing championship medals, but only Sam Holloway repeated as champion from the previous year. Teammate Jack Townsley, who had won in 1949 at 112 pounds, finished second at 120.

Eastern and coach Don Johnson grabbed the first of two consecutive titles in 1951, topping Ann Arbor, 56-52, with East Lansing finishing a distant third with 26 points. Pete Christ of Battle Creek Central became the first Bearcat (and only the second athlete from a school other than Eastern, Sexton or Ann Arbor) to bring home an individual wrestling title, with a decision over Lansing Eastern’s Vince Malcongi in the 140 classification. “The Bearcat matmen took fourth in the State,” according to the Battle Creek yearbook. “Mr. Donald Cooper took over the coaching duties when Mr. Allen Bush was called to the Marines.” (Bush would later serve as executive director of the MHSAA).

Eastern and coach Don Johnson grabbed the first of two consecutive titles in 1951, topping Ann Arbor, 56-52, with East Lansing finishing a distant third with 26 points. Pete Christ of Battle Creek Central became the first Bearcat (and only the second athlete from a school other than Eastern, Sexton or Ann Arbor) to bring home an individual wrestling title, with a decision over Lansing Eastern’s Vince Malcongi in the 140 classification. “The Bearcat matmen took fourth in the State,” according to the Battle Creek yearbook. “Mr. Donald Cooper took over the coaching duties when Mr. Allen Bush was called to the Marines.” (Bush would later serve as executive director of the MHSAA).

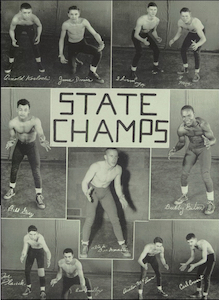

Johnson’s squad absolutely dominated the field in 1952, topping Sexton the next year, 68-43. Ann Arbor followed with 39 points. Seven Quakers – George Smith (95), Herb Austin (103), Jim Sinadinos (127) Bob Ovenhouse (133), Bob Ballard (138), Ed Cary (145) and Norm Thomas (175) – all won their final matches. Both Austin and Sinadinos were repeat champions.

Sexton flipped the table in 1953 with a 67-46 win over Eastern. Ten Big Reds competed for individual state championships among the 12 classifications, with five taking home titles. The Big Reds’ Ken Maidlow, jumping from 165 pounds to 175, and Eastern’s Ed Cary, who moved up to 154, both repeated as medal winners. In the heavyweight class, Sexton’s Ray Reglin downed Steve Zervas from Hazel Park. (Zervas, a two-time runner-up, later wrestled at the University of Michigan, then coached wrestling at Warren Fitzgerald for 34 seasons and served as mayor of Hazel Park from 1974 to 1986).

In 1954, Ossie Elliott of Ypsilanti and Henry Henson of Berkley became the first wrestlers from non 5-A schools to win individual state wrestling titles. Elliott, who had finished as state runner-up in 1953 at 133 pounds, downed Lansing Sexton’s Tom Holden in the same classification. Henson earned a decision over Lansing Eastern’s Ken Bliesener at 154 pounds. Eastern again returned to the winner’s circle, outdistancing Sexton, 60-44. Ypsilanti finished third with 34 points.

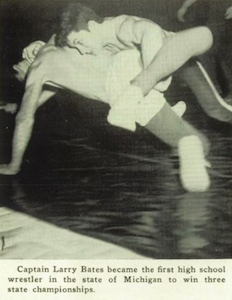

By 1955, athletes from 28 high school teams were battling for state team and individual honors on the mats at MSC’s Jenison Field House. As a senior captain, Lansing Eastern’s Larry Bates pinned four out of five opponents in the 112-pound class to become Michigan’s first wrestler to earn three state crowns. Bates grabbed his first title in 1953, competing at 95 pounds, followed by his second in 1954 at 103. Eastern picked up its second-straight team trophy, racking up 102 points on the way to a fourth crown in the eighth year of championships. For the first time, a non-5-A school finished second, as the Ypsilanti Braves grabbed runner-up honors with 84 points.

Coach Bert Waterman led Ypsilanti to the first of four championships during a 10-year span in 1956. Two Braves, Ambi Wilbanks and Walt Pipps, earned titles while three others finished second in their classifications. Ypsi had lost one dual meet during the regular season, to Lansing Eastern, by a slim three-point margin. With the 1967-68 school year, Waterman would embark on a 24-year career as coach at Yale University after posting a 192-35-4 mark in 16 seasons at Ypsilanti. A 1950 graduate of Michigan State, the former Spartans wrestler would join Eastern’s Don Johnson, Sexton’s Iggy Konrad, Fran Hetherington from the School for the Blind and two other high school coaches as a charter member of the Michigan Wrestling Hall of Fame in November 1978.

Coach Bert Waterman led Ypsilanti to the first of four championships during a 10-year span in 1956. Two Braves, Ambi Wilbanks and Walt Pipps, earned titles while three others finished second in their classifications. Ypsi had lost one dual meet during the regular season, to Lansing Eastern, by a slim three-point margin. With the 1967-68 school year, Waterman would embark on a 24-year career as coach at Yale University after posting a 192-35-4 mark in 16 seasons at Ypsilanti. A 1950 graduate of Michigan State, the former Spartans wrestler would join Eastern’s Don Johnson, Sexton’s Iggy Konrad, Fran Hetherington from the School for the Blind and two other high school coaches as a charter member of the Michigan Wrestling Hall of Fame in November 1978.

Runner-up in 1956, Eastern grabbed another title in 1957 topping Battle Creek Central, 93-89, in the tournament standings. It was a surprise “going away present” for Coach Don Johnson, who was stepping away after 10 seasons of coaching the Quakers to accept the assistant principal position at Eastern. Battle Creek had five wrestlers advance, and held a 56-48 lead over Eastern as the teams entered the final round. The Quakers’ Ted Hartman opened the day with a victory in the 98-pound weight class, helping Eastern post a 3-1 record in championship round matches. Sexton assisted with the Eastern victory when Norm Young defeated Battle Creek’s Bob McClenney in the 120 weight class. The Bearcats, who had five wrestlers in the finals, ended with two individual champs on the day and their highest finish in their 10 seasons of wrestling.

Runner-up in 1956, Eastern grabbed another title in 1957 topping Battle Creek Central, 93-89, in the tournament standings. It was a surprise “going away present” for Coach Don Johnson, who was stepping away after 10 seasons of coaching the Quakers to accept the assistant principal position at Eastern. Battle Creek had five wrestlers advance, and held a 56-48 lead over Eastern as the teams entered the final round. The Quakers’ Ted Hartman opened the day with a victory in the 98-pound weight class, helping Eastern post a 3-1 record in championship round matches. Sexton assisted with the Eastern victory when Norm Young defeated Battle Creek’s Bob McClenney in the 120 weight class. The Bearcats, who had five wrestlers in the finals, ended with two individual champs on the day and their highest finish in their 10 seasons of wrestling.

An All-American wrestler at Michigan State, Johnson would remain at Eastern throughout his education career, retiring as principal in 1983. The fieldhouse at Eastern was named after him in December 1984, fittingly just prior to the championship round of the annual Eastern High Wrestling Invitational.

Eastern again went back-to-back, topping Sexton, 88-57, with Ypsilanti third in the 1958 championship standings. The meet, culminating with 16 boys competing in each weight division – four each from regionals hosted at Battle Creek, Lansing, Ypsilanti and Berkley – was held at the Intramural Building at the University of Michigan. Both Eastern and Sexton advanced four wrestlers to the final round, with Eastern’s Gary Gogarn (95), Ron Parkinson (145) and Alex Valcanoff (154) earning titles. For Sexton, Fritz Kellerman (133) and Wilkie Hopkins (138) finished on top.

The 1959 championships, hosted at the new intramural building at MSU, found boys from 47 schools chasing medal honors.

“Points toward the team title are awarded one for each bout won, with an extra point for a fall,” noted the Lansing State Journal, explaining the mechanics of the tournament. “The big scoring chance comes (in the final round) with a first place netting 10 points, second 7, third 4 and fourth 2.”

Jackson and Sexton had tied for the 6-A Conference crown (the league renamed with the addition of Kalamazoo Central to the mix) and the race to the MHSAA title was expected to be a tight one. Jackson qualified seven for the semifinal round, with four advancing to the championships. The Big Reds sent five wrestlers to the last round. Vikings Ron Shavers (95), Nate Haehnle (145) and Don Mains (165) had each won matches, while Sexton’s qualifiers Tom Mulder (127) and Emerson Boles (175) had earned titles.

With one match remaining, Jackson trailed Iggy Konrad’s Big Reds by four, 67-63, as the Vikings’ Ed Youngs – the state’s reigning heavyweight champion – squared off with Sexton’s Mickey Devoe. Youngs grabbed a 3-1 decision to repeat, but the Vikings needed a fall in the match for a tie. Hence, the Big Reds eked out a single-point victory, 74-73, to escape with their third state mat title.

The results of the title round of the 1960 tournament, also won by Sexton, telegraphed how far the sport had come. Wrestlers from a dozen high schools squared off for honors in the title matches, with winners representing 10 cities. The Big Reds topped Ypsilanti 70-64, followed by Kalamazoo Central with 56 points. Eight other schools had scored at least 20 points in the tournament; 31 teams had scored at least a point. Tom Mulder of Sexton was the lone repeat champion.

With 112 schools now offering wrestling on their sports menu, the MHSAA split the event into two parts for the 1959-60 school year, with Class A set for the University of Michigan and Class B hosted by Michigan State University. The sport was now in full bloom.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

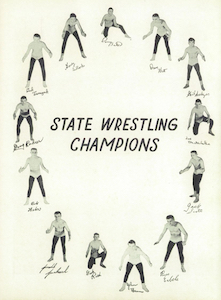

PHOTOS: (Top and 4) Lansing Sexton won the first MHSAA Finals in wrestling in 1948. (2) Eastern’s Larry Bates became the first three-time individual champion in MHSAA history in 1955. (3) The Big Reds were led by coach Ignatius Konrad. (5) Lansing Eastern kept the championship in the capital city in 1949. (6) Bert Waterman built one of the state’s top programs at Ypsilanti. (7) Don Johnson was the architect of Eastern’s program.(Photos gathered by Ron Pesch.)

With Final Takedown, Goodrich's Phipps Arrives at Championship Destination

By

Drew Ellis

Special for MHSAA.com

March 4, 2023

DETROIT – A journey that had been 13 years in the making finally ended with a dream come true for Goodrich junior Easton Phipps.

Since he began wrestling at age 4, Phipps had been focused only on winning a state title.

At Saturday’s Division 2 Individual Finals, Phipps (41-4) had to tap into everything he had worked for to win the 190-pound championship.

After a 1-1 tie through three periods with Clio’s Jacob Marrs (37-5), the two remained tied after the sudden victory stage.

Things came down to the ultimate tiebreaker, which saw Phipps score a takedown to win.

“That state title is what was pushing me,” Phipps said. “I wanted to avenge all my teammates that didn’t get the shot to get a state title. I worked for them and the whole town. I get my picture on the wrestling room wall now.”

The junior said his championship match just came down to will power, as the two cancelled each other out in skill.

“I don’t really know what to say; the skill wasn’t there, it was just about toughness when it got into overtime,” Phipps said.

106

Champion: Brady Baker, Stevensville Lakeshore, Soph. (48-2)

Major Decision, 9-1, over Cristian Haslem, St. Clair, Fr. (46-2)

Baker had control throughout the whole match as the sophomore took home his first Finals championship.

He hit multiple takedowns and a reversal to keep Haslem from getting into the match.

“Things played out well,” Baker said. “I was getting into my attacks, scoring early and often. That’s what you have to do if you want to win.”

Baker failed to place at last year’s Finals and was motivated all season because of that. That motivation pushed him to a championship.

“It means a lot to not place last year and come in this year and win a state title,” Baker said. “It had been on my mind a lot, but there’s still bigger things to come.”

113

Champion: Malachi Kapenga, Hamilton, Soph. (48-4)

Decision 6-4 (OT) over Carter Cichocki, Lowell, Soph. (31-9)

The longest seconds of Kapenga’s life occurred as he awaited a referee’s decision at the end of the third period.

Trailing Cichocki 4-3, Kapenga managed to score an escape as the round ended, but also looked as if he may have had a takedown. Referees conferenced on whether he escaped in time, or even potentially won.

After ruling Kapenga got the escape point, he then went on to score a takedown in sudden victory to win his first Finals championship.

“I just was waiting and praying that they would at least give me one point,” Kapenga said. “I knew if I got the one point, I was at least still in the match. I was expecting a win or a loss, so getting the point, I was happy to at least be going into overtime.”

The match with Cichocki was back-and-forth, with both wrestlers holding leads during the first three rounds.

“It was a hard-fought match, and I had to be smart with my shots,” Kapenga said. “To win feels amazing. I have been working very hard toward it.”

120

Champion: Jackson Blum, Lowell, Soph. (39-3)

23-8 Technical Fall (4:52) over Tayden Miller, Mason, Sr. (37-2)

Blum was very workmanlike in winning a second championship.

The Lowell sophomore scored takedown after takedown to pick up the tech fall victory in the third period.

“There can be some built-up anxiety as you approach the match, but it’s just about getting into what you know you can do and the pressure goes away,” Blum said.

The pressure of a second consecutive title never seemed to get to Blum during the season, as he kept his focus on getting better each day.

“You feel that pressure, but you just have to block it out and do what you do in practice each day,” Blum said. “If you put in the work, the rest takes care of itself.”

126

Champion: Marcello Milani, Orchard Lake St. Mary’s, Sr. (50-0)

Decision, 3-0, over Bryce Shingelton, Linden, Sr. (45-3)

Milani had to wrestle a flawless match to get past Shingelton.

A first-round takedown got him off to a good start, and an escape in the third was the insurance point he needed to grind out the victory.

“I was just trusting in my wrestling, trusting in what I could do,” Milani said of what carried him through the match. “I have trained for this and had to trust that I did the work.”

The Orchard Lake St. Mary’s senior was able to cap off his career with a perfect 50-0 record on top of the title.

“This is something I really wanted since I was a freshman,” Milani said. “I am really glad I got to close it out this year.”

132

Champion: Grant Stahl, Mount Pleasant, Sr. (41-0)

Decision, 12-9, over Aaron Lucio, Stevensville Lakeshore, Sr. (49-2)

The long road to a Finals championship brought a lot of tough moments for Stahl, but it paid off Saturday.

The Oilers senior finished his career with a perfect season record capped by a 12-9 thriller against Lucio.

“This means everything. I had finished second and third and missed a year because of COVID,” Stahl said. “I have given everything to get this, and it feels incredible to finally get it. I wanted it so bad.”

Stahl was able to go up 8-1 thanks to a set of near-fall points early in the third period. He then had to fend off an aggressive Lucio to hang on for the championship.

“(Lucio) just shot in deep and he was sitting there, so I just reached back and hooked his arm, tilted him up and that was the difference,” Stahl said.

138

Champion: Jayden Schwartz, Charlotte, Sr. (52-2)

Decision, 11-5, over Owen Segorski, Lowell, Soph. (29-7)

Trailing 4-2 going into the third period, Jayden Schwartz knew it was time to go into overdrive.

Trusting in his stamina, Schwartz came out aggressive in the third and scored nine points to get past Segorski, a 2022 champion.

“All the work I have put in over the last few weeks, it was all for that third period,” Schwartz said. “I knew I had the stamina for the third to really push the pace.”

The top-seeded Schwartz finished with 52 wins while ending his prep career as a champion.

“This feels amazing,” Schwartz said of the title. “It hasn’t really hit me yet, but all the hard work really paid off.”

144

Champion: CJ Poole, Lowell, Sr. (31-8)

Injury Stoppage (5:00) over Louden Stradling, Gaylord, Sr. (50-1)

The final match of the night ended with unfortunate circumstances.

Tied 1-1 in the third, Poole shot in for a takedown on Stradling. The two collided heads and the impact from the shot, which finished out of the circle, left Stradling unable to continue.

Stradling suffered a head injury, and the match was ruled over and awarded to Poole.

“He’s a back-up-and-shoot kind of wrestler and I saw he was backing up and getting ready to shoot, so I shot for a double. He lowered his level and we hit heads and I was just trying to drive through on my shot,” Poole said.

The way the match ended wasn’t likely how Poole envisioned it, but he’s still grateful to be a champion.

“It still feels amazing,” Poole said of the title. “It’s been a lot of work.”

150

Champion: Trevor Swiss, Petoskey, Sr. (47-0)

Decision, 10-4, over Jack Conley, Lake Fenton, Sr. (31-3)

Swiss completed an unbeaten season, and the Petoskey senior never trailed in this match.

Going into the third period tied 4-4, Swiss picked up the pace and outscored Conley 6-0 to secure the championship.

“I knew I had to work, so I just came out knowing I needed to make something happen,” Swiss said. “I was able to capitalize when he got off-balanced, so I managed to put him on his back.”

Despite the unbeaten season, it was the Finals title that Swiss had been craving all year, fulfilling a childhood dream.

“This is what I have been dreaming of since I was in first grade,” Swiss said. “It feels amazing, and I really can’t put it into words.”

157

Champion: Cory Thomas Jr., Pontiac, Jr. (26-0)

Decision, 5-1, over Zach Jacobs, Jackson Northwest, Sr. (39-3)

After a scoreless first period, Thomas Jr. managed to ride out Jacobs in the second period to keep the match at 0-0.

In the third, Thomas Jr. knew he had put himself in position to win, which he did with an early escape and two takedowns during the closing two minutes.

“I work really hard at home, and I think that showed in being able to get those late takedowns,” Thomas Jr. said. “I was able to just keep pushing through.”

Thomas Jr. placed third at the 2021 D1 Finals at 125 pounds wrestling for Detroit Catholic Central, but being able to come back this year to win a title for Pontiac was even more rewarding.

“It’s been a crazy journey. I’m just so happy to be able to experience this,” Thomas Jr. said.

165

Champion: Philip Lamka, Fenton, Jr. (44-2)

Decision, 6-5, over Max Macklem, Goodrich, Soph. (33-5)

After placing third at last year’s Finals, Lamka wouldn’t let himself experience disappointment again.

He trailed Macklem 5-4 in the third period, but scored a late takedown to edge his opponent by one point.

“I’ve worked so hard for this all year,” Lamka said. “After last year, this is all I wanted. Coming up short in the semifinals in overtime to the eventual champ (in 2022) was hard. Coming in, I had one job to do and that was to win. I got it done.”

Following the victory, Lamka dropped to his knees and took in the moment.

“This is everything I have worked for my whole life,” Lamka said. “After coming up short before, (the emotions) just flood you.”

175

Champion: Brayden Gautreau, Gaylord, Sr. (52-1)

Decision, 3-1 (OT), over Carson Crace, Lowell, Sr. (33-6)

For Gautreau to come up with a second-consecutive championship, he needed a little more time. The senior was tied 1-1 with Crace through three periods after each scored an escape.

In OT, the past champ showed his mettle and came through with a takedown to earn the victory.

“I was on my stuff,” Gautreau said of the OT period. “(Crace) did a good job of keeping me off during most of the match. I just kept attacking, and it eventually paid off.”

Gautreau won the D2 171-pound title last year but said he never felt a lot of pressure to repeat.

“I didn’t feel a lot of the pressure. I just love wrestling, so I just love being able to compete,” Gautreau said. “You put in a lot of work for these moments, and this is where champions shine.”

215

Champion: Adam Haselius, Jackson Northwest, Sr. (50-0)

Decision, 5-1, over Joey Scaramuzzino, Croswell-Lexington, Jr. (51-4)

Haselius likes to be consistent, and he was very consistent Saturday night.

The Jackson Northwest senior claimed a second-consecutive Division 2 title after winning at 189 pounds in 2022.

“It feels great to repeat,” Haselius said. “Obviously that has been the goal since last year. It just comes down to consistency for me. Nobody that wins a state championship believes that they can’t win it again.”

Haselius never trailed, as he set the tone early with a takedown and added another in the second period before grinding out the victory in the third.

“I just wanted to keep myself in good positions,” Haselius said of the match. “Once I got the lead, I knew it was on him to bring the pressure, so I just had to wrestle smart.”

285

Champion: James Mahon, Goodrich, Soph. (14-0)

Decision, 5-4, over Aaron Holstege, Allendale, Sr. (49-1)

Battling through a labrum injury, Mahon managed to ride out Holstege for the final minute to secure a one-point victory.

“In a lot of my matches this year and last year, I’ve had to find ways to win 1-0 or win by one point,” Mahon said. “I’ve always found ways to get it done.”

Mahon trailed 4-3 in the third period, but scored a takedown with a minute left to go ahead and then worked on his top game to earn his first Finals title as a sophomore.

“I really expected this the whole year,” Mahon said. “It was never in doubt for me. Now I have to go and get two more.”

PHOTOS (Top) Goodrich’s Easton Phipps takes a champion’s photo at Ford Field. (Middle) Jackson Northwest’s Zach Jacobs, front, works to break the hold of Pontiac’s Cory Thomas Jr. on Saturday. (Click for more from High School Sports Scene.)