'I just wanted people to go the right way'

September 12, 2017

By Geoff Kimmerly

Second Half editor

They were running in the dark – a key scene-setting detail to keep in mind.

So being familiar with the course surely gave St. Johns’ cross country runner Taryn Chapko an edge during her school’s Under the Lights Invitational on Aug 18.

So being familiar with the course surely gave St. Johns’ cross country runner Taryn Chapko an edge during her school’s Under the Lights Invitational on Aug 18.

And yet, she didn’t take advantage of it as much as she could have – making the first night of her sophomore season more memorable both for Chapko and the competitor who crossed the line first that evening.

The 5K course was lit in many places by large construction lamps, lights from the tennis courts or other portable fixtures set up to mark the way. But admittedly, some points were a little dim. And that’s where Chapko became a guide, yelling to a small pack of frontrunners ahead of her when to turn.

That probably doesn’t seem like a big deal – unless you’re Goodrich junior Jillian Lange. Lange ended up winning the race in 19:16. Chapko finished third in 19:48 – instead of first, which might’ve been the case especially if she had allowed the leaders to continue taking a wrong turn about a mile in.

Going the wrong way could’ve meant turning around, doubling back and losing time – or being disqualified for cutting the course shorter.

“I know a lot more people (this year) just from running, from other schools. We’re all doing the same thing. We all want to get better. I like helping people get better,” Chapko said. “It’s the first race, and they want to feel good about themselves for the rest of the season, because if you had a bad first race you might start getting down on yourself. And I don’t want people to be upset, especially with a race that’s so much fun.”

To be honest, Chapko didn’t think her little bit of directing was a big deal either – until St. Johns administrators received an email two weeks ago from Goodrich athletic director Dave Davis, who expressed his appreciation for her sportsmanship after hearing about it both from Lange and his cross country coaching staff. “Please relay to Taryn and your coaches my appreciation for this simple act of sportsmanship and kindness,” Davis wrote. “We need more of that.”

To be honest, Chapko didn’t think her little bit of directing was a big deal either – until St. Johns administrators received an email two weeks ago from Goodrich athletic director Dave Davis, who expressed his appreciation for her sportsmanship after hearing about it both from Lange and his cross country coaching staff. “Please relay to Taryn and your coaches my appreciation for this simple act of sportsmanship and kindness,” Davis wrote. “We need more of that.”

“I just wanted people to go the right way,” Chapko said, recalling the race last week. “I saw the email and I was like, ‘It’s bigger than I thought.’

“I guess it doesn’t happen too often.”

Or at least not as much as it should – which, again, should make this race stick out among the many both will run over the next few seasons of their high school careers.

This was the third year St. Johns has hosted the opening night meet. The first race goes off at 9:30 p.m. It’s a neat way to change up the 5K distance these runners will tackle a number of times over the following three months.

But admittedly, starting after dusk leaves a couple of dark spots on the course – especially behind the tennis courts and near a barn about a mile in to the first of two laps, where Lange and the frontrunners with her nearly left the path.

This was the first time Goodrich took part in the Under the Lights race, and Lange said this week that she remembers feeling like a little bit of an “outsider” starting out because her team hadn’t run in the event before. But when Chapko yelled out which way to go, that changed.

“It was out of nowhere, she’d be like ‘left,’ or ‘turn right,’ or ‘go around this,’” Lange recalled. “It was really great of her to think of me as another person she could help.

“In cross country, you’re racing against these people (and) it can get pretty harsh out there. You want to win. Just the fact she was kind enough to let me stay on course, because at some points she was pretty close to me and she could’ve gone in front when I was in front because I screwed up and went too far. She was just being honest in the race, and that’s what I like about it. The kindness really makes the race what it is, because that was fair.”

The pair of standouts had crossed paths before. In both runners’ last cross country race before meeting again at St. Johns, Lange finished seventh at the Lower Peninsula Division 2 Finals in a time of 18:49. Chapko was 10th in 19:06. So finishing ahead of someone who had beaten her the last time out would have been an incredible way for Chapko to start this season – but not because Lange got lost.

There’s a kinship among distance runners, longtime Redwings coach Bob Sackrider has noticed over the years, and Chapko gets it. She also knows what it’s like to get off-course – she did so once as a freshman, and Sackrider has talked with his teams about how to handle that situation.

There’s a kinship among distance runners, longtime Redwings coach Bob Sackrider has noticed over the years, and Chapko gets it. She also knows what it’s like to get off-course – she did so once as a freshman, and Sackrider has talked with his teams about how to handle that situation.

“Obviously there’s an enormous sense of pride that others recognized what we’re working toward,” Sackrider said of Davis’ note. “And I was thrilled that Taryn was able to have the wherewithal in the moment to employ what we’ve been talking about. It’s one thing to talk about it; it’s another thing to actually do it and actually be aware enough in the middle of the race to do it.”

Both runners have similar goals moving forward this fall. Both have times they are shooting to beat (and Chapko just did) – she said last week she was looking to break 19 minutes and she did so Saturday with an 18:56 at Bath, while Lange is hoping to break 18 after posting an 18:20 last October.

They both also are shooting to get their teams back to Michigan International Speedway and the MHSAA Finals on Nov. 4 – the next time the two are expected to cross paths again.

“It’ll be touching I guess. You make these friends, and you never see them, but you’re automatically just friends … (because) you have these similarities,” Lange said. “You can go up to a random person and be like, ‘Remember that time?’ That’s what I’m looking forward to.”

Geoff Kimmerly joined the MHSAA as its Media & Content Coordinator in Sept. 2011 after 12 years as Prep Sports Editor of the Lansing State Journal. He has served as Editor of Second Half since its creation in Jan. 2012. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for the Barry, Eaton, Ingham, Livingston, Ionia, Clinton, Shiawassee, Gratiot, Isabella, Clare and Montcalm counties.

Geoff Kimmerly joined the MHSAA as its Media & Content Coordinator in Sept. 2011 after 12 years as Prep Sports Editor of the Lansing State Journal. He has served as Editor of Second Half since its creation in Jan. 2012. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for the Barry, Eaton, Ingham, Livingston, Ionia, Clinton, Shiawassee, Gratiot, Isabella, Clare and Montcalm counties.

PHOTOS: (Top) Runners take off from the start of the Under the Lights Invitational last month. (Middle) Goodrich’s Jillian Lange pushes through the midpoint of last season’s Final at MIS. (Below) St. Johns’ Taryn Chapko sprints down the final stretch of the championship race last fall. (Top photo courtesy of St. Johns cross country, middle and below by RunMichigan.com.)

Cross Country Builds Century-Long Run of Starts & Finishes

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

December 30, 2021

Conditions weren’t ideal in Ypsilanti on this November morning in 1950.

The track at Washtenaw Country Club was snow-covered. Strong, cold wind and sub-freezing temperatures greeted runners. As in years past, Michigan State Normal College (MSNC), today known as Eastern Michigan University, was playing host to the Michigan High School Athletic Association’s cross country championships.

According to preliminary Associated Press coverage of the meet, “Kalamazoo Central won the Class A state high school cross-country championship. Ann Arbor placed second. The races were held at (MSNC) over a two-mile course. Individual winners from the 23 schools competing in the Class A event were James Arnold of Battle Creek, first and James Bishop, of Kalamazoo, second.”

Alma emerged from a field of 24 schools as the victor of the Class B race. Lansing Everett finished first among 14 schools in Class C-D that afternoon.

But, unmentioned in initial coverage, there was a hitch in the Class A race that day. A total of 25 teams had entered the race – the first of the day. Due to a scheduling mishap, two teams - Grand Rapids Catholic Central and Battle Creek Central, both strong candidates to win the competition – had been “literally left standing at the starting gate.”

“Originally scheduled to get underway at 11:30,” stated the Grand Rapids Press in its evening coverage of the morning’s race, “the run actually started at 11:20. Catholic and Battle Creek squads were both on hand, but were not notified of the change in time.”

“It all happened when the Bearcats had taken their warmup trots and had 50 minutes to go before the Class A event was slated to get underway,” reported the Battle Creek Enquirer in coverage the following day. Told the event would start as scheduled at 11:30, the Bearcats sought warmth, before they “returned to the course at about 11:17 – just in time to see the Class A field go past.”

Like Battle Creek, Catholic had headed to the clubhouse before the race, returning to the course to discover the pack had left.

James Arnold of Battle Creek, one of the event’s top runners, quickly recognized what was happening, and “sauntered into the pack of 161 runners after the start …” noted the Enquirer, reporting the chaos.

“(The) runner was 50 or so more yards down the stretch when he noticed the swarm of thinclads romp by him,” stated the Press, adding color to the moment. “He quickly doffed his sweat suit and took pursuit. He was Jim Arnold, who incidentally, came in the winner.”

“So befuddled were the officials,” said the Enquirer, “that they let Arnold be crowned individual champion and gave him a time of 10 minutes and 45 seconds even though he didn’t get under way at the starting line. But the other Bearcat entries weren’t so fortunate and finished far back to place the Bearcats far down the list.”

“He should be given a lot of credit for his performance,” stated the Press, “but on the other hand, is he legally entitled to the honor? He didn’t run the regulation distance that the other boys covered?”

Immediately following, and in the days after the race, formal protests were lodged by various coaches with the MHSAA.

“It certainly was an injustice as far as Catholic’s Joe Host was concerned,” Grand Rapids Union coach Lowell Palmer told the Press. Host was the Class A individual winner in 1949 and was returning to defend his title. “It probably would have been his last prep meet, and he deserved a better fate.”

Harriers in the Great Lakes State

Readers interested in the sport’s entire history should make a dash for a copy of Jeff Hollobaugh’s book, XC! High School Cross Country In Michigan. At 270 pages in length, it “brings to life the traditions and memories of the most challenging of high school sports.” The author – or at least his voice – is well-known to many as the announcer at MHSAA cross country and track meets. For those with more than just a passing interest, he also maintains Michtrack.org, the place to go for everything running.

What was considered the first true State High School Track and Field Championships in Michigan was held in the spring of 1908 at Michigan Agricultural College (MAC), today known as Michigan State University (MSU). So, it should come as no surprise Michigan’s first planned prep cross country state title meet would be planned for the same place.

What was considered the first true State High School Track and Field Championships in Michigan was held in the spring of 1908 at Michigan Agricultural College (MAC), today known as Michigan State University (MSU). So, it should come as no surprise Michigan’s first planned prep cross country state title meet would be planned for the same place.

The desire to host a meet was, in all likelihood, self-centered. What better way to recruit future distance runners than to invite all the state’s best high school runners to an event hosted at your campus?

Chester L. Brewer, athletic director at the college, announced plans to host a state interscholastic cross country meet in East Lansing in the fall of 1921. According to author Mark E. Havitz, the first school ran its first cross country race in 1907. The University of Michigan, which had organized a cross country club in 1901 to train distance runners in track, began official varsity cross country competition with the 1919-20 school year.

An announcement in the Benton Harbor News Palladium in its Nov. 4 edition detailed the basics. “This meet, the first of its kind in the history of state athletics, is expected to bring together the best long distance runners in Michigan schools. The race will be over a three mile course, instead of the five miles to be run by college athletes … . Floyd Rowe, state director of physical education, will be in charge.”

The Bay City Times on Nov. 8 added detail.

The “chief aim is to develop cross country in the secondary schools of Michigan … . While several schools, such as Battle Creek, Kalamazoo, Highland Park, Ypsilanti, and others are already strong in distance running, those in many other sections never go beyond the mile or possibly the two-mile in their track activities.”

Interestingly, Rowe also held another title, omitted from the announcements.

“Floyd Rowe, State Physical Training Director, will coach the (cross country) team this fall,” stated the Sept. 30, 1921, edition of the MAC. Record, a weekly published by the school’s alumni association. “Rowe, who is an old Michigan distance star, has had a lot of experience and should get the best out of his men. He is living at East Lansing at present.”

“The visiting lads will have an opportunity to witness Armistice Day ceremonies” scheduled at MAC for the November 11th meet. In addition, a trophy for the top five-man team was up for grabs along with 10 medals, one gold, one silver, and eight bronze for individuals.”

However, Mother Nature intervened, smothering those plans.

“Nineteen inches of snow which fell at East Lansing on Tuesday and Wednesday of last week blocked the college cross country course to such an extent that the First Annual M.A.C. High School Cross Country Run, scheduled for Friday, November 11 was indefinitely postponed,” stated a report in the Record, published on the 18th of that month. “While it is not likely that an attempt will be made to hold the run later this season, Director C. L. Brewer announces that the event will be held next fall and established as an annual event.”

Only, that didn’t happen.

Rather, the “first official state high school championship cross country run” – sanctioned by the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association, the immediate predecessor to the modern-day MHSAA – was held at Michigan State Normal College in Ypsilanti in November 1922 on Armistice Day.

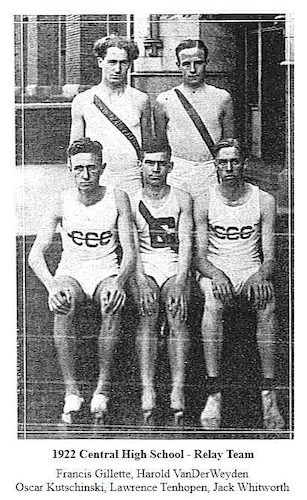

The meet, held under the direction of MSNC’s new coach and athletic director, Lloyd W. Olds, included 12 schools, including Battle Creek, Ann Arbor, Kalamazoo, Central and Union from Grand Rapids, and numerous Detroit high schools.

Ann Arbor topped the field, finishing with 27 points to Detroit Northwestern’s 96, followed by Battle Creek at 101. Junior Oscar Kutschinski of Grand Rapids Central topped the field, covering the two and a half mile course at 13:28, trailed by Theodore Hornberger of Ann Arbor, “a distance of about 20 feet separating the pair,” according to Ann Arbor News coverage of the meet. (While the two never met, Kutschinski’s great-nephew, Ron, won the MHSAA’s 1963 Class B 880 running for East Grand Rapids, then claimed the Lower Peninsula individual cross country title in 1964. The winner of the Big Ten half-mile while at the University of Michigan, Ron also represented the U.S. at the 1968 Olympics.)

Competition for runners at the collegiate level in Michigan had been growing across the state. Michigan Normal had started its program in 1911 and, under the guidance of Coach Olds, the school’s track and cross country programs developed into national powers. Men's cross country became a championship sport in the fall of 1922 for the Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association (MIAA) – America’s oldest collegiate conference, formed in 1888. Kalamazoo College was that league’s first XC champion, topping MSNC (a member of the MIAA from 1892 until 1926), Albion, and Olivet.

Competition for runners at the collegiate level in Michigan had been growing across the state. Michigan Normal had started its program in 1911 and, under the guidance of Coach Olds, the school’s track and cross country programs developed into national powers. Men's cross country became a championship sport in the fall of 1922 for the Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association (MIAA) – America’s oldest collegiate conference, formed in 1888. Kalamazoo College was that league’s first XC champion, topping MSNC (a member of the MIAA from 1892 until 1926), Albion, and Olivet.

The 1923 state meet at MSNC, run under muddy conditions, saw individual honors go to LeRoy Potter of Coldwater while the Ann Arbor team won its second consecutive title.

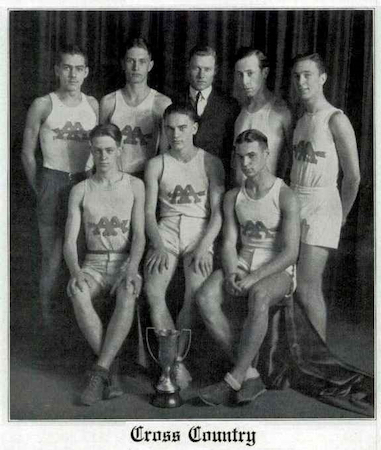

Ann Arbor picked up its third-straight team championship in 1924, earning “permanent possession of the M.S.N.C. trophy,” according to the Detroit Free Press. Ann Arbor High records show the school also claimed state titles for 1919, 1920, and 1921 as well, based on finishes in an annual Detroit Thanksgiving Day run. The school’s next team title wouldn’t arrive until 1987.

Potter “repeated and hung up another record, beating (his) old mark by 17 and 1/5 seconds,” to become the meet’s first two-time winner. “He led the group from the start, and finished with a strong sprint, being a full 500 yards ahead of the second man, Van Mere, of Kalamazoo. Donner of Ann Arbor was third.”

After graduation, Potter attended Michigan State Normal and became the school’s “first track performer to earn All-America status when he captured the mile run title at the 1928 NCAA Championships.”

The Ypsilanti meet continued without change when the MHSAA took charge of prep athletics in Michigan midway through the 1924-25 school year. To conclude the Fall 1925 season, Kalamazoo Central won the “hill and dale” gathering with five finishers in among the first 15, with Ann Arbor ending in second, 36 to 52. Detroit Northwestern finished in third with 61. Lloyd Cody from Ann Arbor “finished the two and a half mile grind in 11 minutes 52 5/10 seconds.” Van Mere of Kalamazoo again finished second.

The Ypsilanti meet continued without change when the MHSAA took charge of prep athletics in Michigan midway through the 1924-25 school year. To conclude the Fall 1925 season, Kalamazoo Central won the “hill and dale” gathering with five finishers in among the first 15, with Ann Arbor ending in second, 36 to 52. Detroit Northwestern finished in third with 61. Lloyd Cody from Ann Arbor “finished the two and a half mile grind in 11 minutes 52 5/10 seconds.” Van Mere of Kalamazoo again finished second.

Over 300 invitations were sent out to different schools for the 5th annual interscholastic run in 1926. A total of 18 teams competed with a field of 105 competitors. Kalamazoo repeated as champs, this time also supplying the individual winner, Raymond Swartz, who clocked in at 14:24.2 over the two and a half mile course. A total of 93 runners finished the race. A trophy that cost the Association $12 was presented to the winning team.

XC Above the Straits of Mackinac

The first cross country meet in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, according to the Escanaba Daily Press, was held in October of 1927 – “just before the Menominee-Escanaba football game” – with three schools, Iron Mountain, Manistique, and Escanaba, scheduled to participate.

“The state athletic association is very much in favor of cross-country running as a high school sport, and A. W. Thompson, state director of athletics has designated the race here as an official upper peninsula event,” added the Daily Press – the sponsor of the meet and donor of a trophy for the winning school. “He was pleased to learn that three schools would participate the first year and predicted that many more would enter runners in the years to follow.

“Cross-country has never been attempted in the peninsula, but high schools below the straits have been developing the sport rapidly.”

“Because Escanaba was the only school entering a full team, it was decided in fairness to the others, to award the trophy” to the school whose runner won the race. James Crummey, a junior and the only entry from Iron Mountain, won the event, “completing the 1 7/8 mile course in 11:35, far ahead of his nearest competitor,” Emmett Lough of Escanaba finished second, followed by two teammates, Tom Froberg, and Irv Cass.

The 1927 state competition at Ypsilanti, now with 27 teams, was split into Class A and Class B for the first time. According to the MHSAA’s January 1928 Bulletin, “a team trophy and 20 medals were awarded for each class.” Swartz of Kalamazoo again won the individual honor, now in Class A, leading his team to its third-straight team championship. All of Kalamazoo’s runners finished in the top 10, allowing the team to repeat as champion.

“After figuring for two hours,” noted the Grand Rapids Press, “the mathematicians decided Detroit Eastern had second and Pontiac third.”

For the first time, the U.P. had entries in a state title race, as Crummey of Iron Mountain and Oliver Cejka of Kingsford made the long trip downstate to compete in Class B.

For the first time, the U.P. had entries in a state title race, as Crummey of Iron Mountain and Oliver Cejka of Kingsford made the long trip downstate to compete in Class B.

Dearborn grabbed the ‘B’ team title. Earl Sonnenberg of Wyandotte Roosevelt earned the classification’s individual crown “after a two mile battle with Crummey,” noted the Press. Brown of Ferndale was third, while Cejka finished sixth.

With the solid showings, the U.P. beamed with pride.

The Sport Grows

The meet was expanded to three classifications with the addition of Class C in 1928. Kalamazoo, again, won the top honor in Class A, defeating Detroit Northwestern, 51-66. Jack Rutherford of Flint Central came away with the individual honor, with a time of 10:23, a “rather good time considering the snow-clad pathway,” noted the Bay City Times. Marcellus Barlage of Detroit Holy Redeemer took Class B in 10:46 while Tompledus (first name not available), Parma’s only runner, finished at 11:52 for the Class C honor. Roosevelt was the only team in the class “that returned five men to the starting or finish line.”

In 1929, the MHSAA reported 68 schools sponsoring XC teams. Because of the continued growth, for the first time, regional meets were hosted by the MHSAA that year, with seven taking place initially. Sonnenberg, who also won the Class B 880 track event in the spring, picked up his second harrier title come fall, this time in Class A for Wyandotte Roosevelt. He had finished second in ‘B’ in 1928 and would later compete for Western State Teachers’ College – today’s Western Michigan University.

The meet saw its first shared title in 1930, when Grand Rapids South, coached by Percy L. ‘Pop’ Churm, deadlocked with Alonzo Stoddard’s Kalamazoo Central squad, with 91 points each, to split honors in Class A. Missing from the South team was future President of the United States, Gerald Ford, who was not a distance runner, but rather one of the “weight men” on Churm’s South track team. The season also marked the first year in which the Detroit Public Schools didn’t compete due to their choice to withdraw from state competition.

In 1931, “Kalamazoo became state champs because they had a well-balanced team,” detailed the school’s yearbook, “in contrast to some teams who have one man who finishes first most of the time while there may be three or four others who finish far down in the standings. Gerald Roberts led the local thinclads to the tape in the State run, finishing sixth, but it was the mass formation of (Arnold) Baker, (Robert) Massey and (Randall) Swartz that brought home the trophy. This group finished 12th, 13th, and 14th respectively while (George) Vande Lester assured Central of the title by crossing the line 25th which is not at all bad considering that there were over 100 men entered.”

With the onset of the Depression, the annual state cross country finals were canceled due to finances, and teams ended their seasons with regional competitions in both 1932 and 1933. The championships disappeared again in 1942 due to World War II. They resumed in 1943. In 1944, the MHSAA sponsored its first split peninsula harrier championships, with Baraga winning their first of back-to-back Class C-D-E titles under Coach Evins Edward Erickson. Iron Mountain topped Escanaba, 15 to 44, in Class B. The 2-mile runs were hosted “between the halves” of the Escanaba-Iron Mountain football game in late October, according to the Escanaba Daily Press.

The Re-Running of the 1950 Class A Meet

“I am not positive we would have won it,” said Battle Creek coach Bob Mowerson, “but I feel sure we would at least have placed second, I’m going to call and tell the story to (Charles) Forsythe, (director of the MHSAA) but I feel little can be done now.”

Before the state final, Battle Creek Central had beaten Kalamazoo Central in three of four previous meets that year. The single defeat, a 28-27 win by the Maroon Giants, had come at home in a dual meet early in the season, hosted at Riverside Country Club. It marked the first dual dropped by the Bearcats in two years.

“Coach Ted Sowle of Catholic thought Battle Creek had too much depth for his team to beat,” stated the Press, “but was of the opinion that the two teams would finish one-two had they been allowed to participate.”

Dave Arnold, assistant state director of athletics, suggested that the meet be rerun the following weekend. Forsythe agreed but decided that since 21 of the 23 teams entered had completed the race, the results of the original run would stand.

“A new title, new set of trophies, and more expense mileage will be available for this second event. The race – a second Class A championship - was scheduled for the coming weekend, and scheduled for 10:30 again at Ypsilanti.

“A new title, new set of trophies, and more expense mileage will be available for this second event. The race – a second Class A championship - was scheduled for the coming weekend, and scheduled for 10:30 again at Ypsilanti.

“Fleet-footed Bearcat ace Jim Arnold scampered across the finish line in the No. 1 position for the second week running, which gives him the distinction of having won top individual honors in the annual high school cross country championship event twice in one year,” noted the Enquirer with glee.

“Jim jumped into the race last week in 80th place, out ran the entire field, and finally sprinted into the winner’s spot in first place. His pace-making time of 10 minutes and 39.5 seconds in yesterday’s race bettered that of his first title run by 5.5 seconds on the same course.” The race-time temperature was 27 degrees.

Just 10 teams and 75 harriers entered the second running, as the results of the original race would still stand. With little to gain, Kalamazoo Central stayed away. Ann Arbor, second in the original race, returned.

“Arnold and Joe Host, Grand Rapids Catholic’s defending individual champion in the event, led the pack for the first half of the race,” added the Enquirer, “running side by side over frigid snow-covered track at Washtenaw golf course. The Bearcat ace pulled away at the three-quarter mark, however, and won going away. Host crossed the finish line in third place as an Ann Arbor harrier sped past him down the home stretch.”

Battle Creek Central won the event with 45 points. Ann Arbor, repeating its second-place performance, topped Catholic Central, which finished third, 69 points to 118.

The annual Lower Peninsula championships remained in Ypsilanti for another 20 years.

Changes

The U.P. championships continued to be hosted in October during football games, alternating between Escanaba and Iron Mountain and run during the annual Saturday contest between those two schools into the mid-1950s before moving to Marquette under management of Northern Michigan University.

In 1961, Detroit schools returned to statewide competition, and, suitably, the Lower Peninsula Class A team championship was won by Detroit Redford at Washtenaw Country Club. Redford’s Dick Sharkey, unbeaten in his 20 races as a junior and senior, finished first, outdistancing Detroit Cody’s Tony Mifsud by 50 yards. That year, the MHSAA added an All-Class individual race for runners “whose teams failed to qualify for the team event”, noted the Detroit Free Press. Tom Florida of Flint Southwestern was the race’s first winner. Individual runs were added to Class B In 1964, and to Class C-D in 1971.

According to Hollobaugh, heavy snow in 1966 caused a one-week delay in the running of the championships. It’s been the only weather-related postponement in the event’s history.

Five Decades of XC

The 1971 championship marked 50 years since the first run in Ypsilanti in 1922. Based on a survey by the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), 472 of Michigan’s high schools now sponsored boys cross country teams.

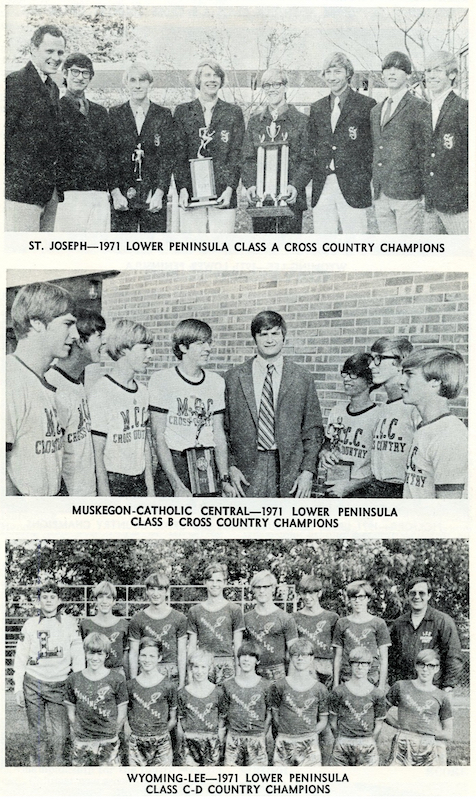

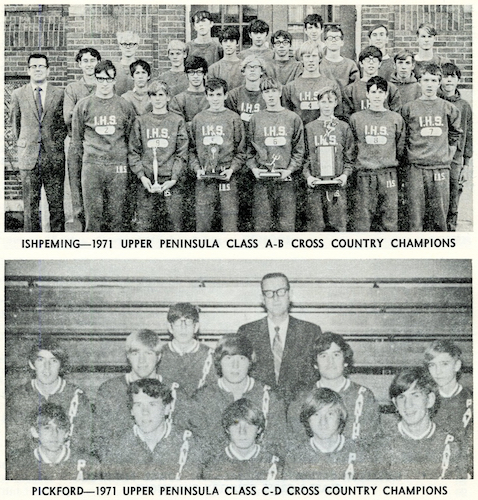

Tim Tobin of St. Joseph grabbed the Class A individual championship and led the Bears – the smallest of the ‘A’ schools based on enrollment – to its first-ever title, 97 to 120 over second-place Flint Kearsley. St. Joseph had previously finished second to Kearsley in both 1968 and 1970. Muskegon Catholic Central grabbed Class B, with Wyoming Lee earning Class C-D. In the U.P., Ishpeming won A-B and Pickford grabbed C-D, staged at Northern Michigan University in Marquette.

Dismal weather had dampened the L.P. meet, run on a newly laid-out 2½-mile course at Washtenaw Country Club, but the races still saw a crowd of “3,000 to 4,000 people” spread around the course according to MHSAA Executive Director Allen W. Bush.

Dismal weather had dampened the L.P. meet, run on a newly laid-out 2½-mile course at Washtenaw Country Club, but the races still saw a crowd of “3,000 to 4,000 people” spread around the course according to MHSAA Executive Director Allen W. Bush.

Nevertheless, the gathering was the last of the long run of consecutive meets hosted by the university.

“In 1971, which is the last year that (they) ran at Washtenaw Country Club, I was at that meet,” recalled Jerry Myszkowski, who ran for coach Bob Parks at Eastern Michigan during its NCAA Division II and NAIA national championship season of 1970. “It was a deluge. It was raining cats and dogs and did not let up. Basically, the course was just a mess. There was standing water … every turn was all torn up.”

“A couple of years before the change, Parks was complaining that he was getting more pushback from members of Washtenaw Country Club about using the course. They were upset that we were going to take a whole day off and not play golf, et cetera, et cetera.”

More and more club members were coming in from beyond the county.

“Park’s statement was, he felt in the old days, most of these members were members of Washtenaw County, Ann Arbor, and Ypsilanti and they took civic pride in this thing,“ continued Myszkowski. “I’m sure that with all those spectators as well as runners, there was already some damage probably done on the course. With the rain, I think that was the last straw.”

“Park’s statement was, he felt in the old days, most of these members were members of Washtenaw County, Ann Arbor, and Ypsilanti and they took civic pride in this thing,“ continued Myszkowski. “I’m sure that with all those spectators as well as runners, there was already some damage probably done on the course. With the rain, I think that was the last straw.”

Minutes from the May 1972 MHSAA Representative Council meeting indicate that the Association planned to make a change in direction for the coming fall.

“The following requests from the Cross Country Committee were reviewed at this meeting. It was decided that a single class final for cross country would be conducted at three different sites as recommended by the Coaches Association and the committee. Class A will be conducted by Detroit-Redford Union, Class B by Vicksburg High School, and Class C-D by Jackson-Vandercook Lake High School. The Upper Peninsula meet will be conducted at Northern Michigan University.”

“With a wet fall, you can really tear up a golf course with that many people on it,” said Rudy Godefroidt, who guided Breckenridge to a Class C title in 1976, then served as an official for three decades. “(The Association) knew that if they separated the meet, they would separate the number of individuals (watching the event).”

The 1972 season included one more additional change, as the distance run by prep XC athletes in Michigan was increased from 2½ to 3 miles.

An NFHS survey showed 42 Michigan schools sponsored cross country for girls during the 1975-76 school year. With the arrival of Title IX, MHSAA-sponsored Lower and Upper Peninsula Open Class girls state championship meets were added to the postseason mix in 1978. A year later, with 221 schools now sponsoring the sport for girls, the Association separated the girls finals into classifications. In 1980, the standard distance of a race moved to five kilometers (3.10686 miles).

Return to a Single Site

Dave Bork, a former cross country runner and later coach at Monroe High School, and past vice president of the Michigan Interscholastic Track Coaches Association, and Mike Woolsey, cross country and track coach at Jackson Lumen Christi and previous president of MITCA, “had been tossing around the possibility of having all schools compete again at a single location,” recalled the Monroe News in 2020. They investigated the possibility of using Michigan International Speedway as the site. “That was in 1994.”

“Fortunately, Woolsey lived in the same neighborhood as (former Jackson Citizen Patriot sports editor and) the public relations director for MIS, Tommy Cameron,” stated the Monroe paper. “Cameron liked the idea and asked then-MIS owner Roger Penske about it. Penske said yes, and then Bork and Woolsey went to work. The two formed an 11-member committee to lay the foundation for MIS to host the state meet.”

Of course, much had changed since 1972. Once the logistics were worked out, the MHSAA event made the move to Brooklyn for the Lower Peninsula meets starting in 1996. Instantly, the cross country championships became the single largest gathering of athletes in the history of the Association, with nearly 1,900 athletes from around 500 schools competing across eight runs – four for boys and four for girls. It was the first state meet in the country to use electric timing, even before any NCAA meet.

Of course, much had changed since 1972. Once the logistics were worked out, the MHSAA event made the move to Brooklyn for the Lower Peninsula meets starting in 1996. Instantly, the cross country championships became the single largest gathering of athletes in the history of the Association, with nearly 1,900 athletes from around 500 schools competing across eight runs – four for boys and four for girls. It was the first state meet in the country to use electric timing, even before any NCAA meet.

“MIS was not only developed as a high-banked, high-speed track for Indy Car and NASCAR events; located to the East of the racing oval was a car testing/road rally course of dips and turns and rolling landscape that two thirds of the race would actually take place on,” stated John Johnson, recently-retired communications director for the MHSAA. “The race would start on the infield before heading to the back course, and finish with the runners reentering the oval at Turn 3 and finishing on the grass skirt of the oval in front of the main grandstand.“

A 300-foot wide starting line also meant that separate team and individual races were no longer needed as the site could accommodate all the runners in a single race.

Still, logistical issues arose with timing the mass of runners, creating unforeseen problems at the first running at MIS

“As I like to say to this day – ‘We’re still waiting on the results of the 1996 Cross Country Finals,’” added Johnson.

MIS officials were concerned with allowing spectators on the course, and hence, all were forced to watch from the main grandstands.

“It wasn’t what they wanted,” stated Johnson.

But, with the efforts from MITCA, the MHSAA, and expanded flexibility from MIS owners and staff, the initial issues marring the event were soon worked out.

More Than 2 Decades Later ...

The Cross Country Finals have been hosted at the Speedway for 26 years. Like Ford Field in football or Breslin Center in basketball, it’s become a destination point that teams can target as their goal for the season.

“The kids themselves (have become) enthusiastic about having a place to call their own,” added Johnson. “The rolling Irish Hills (have produced) incredibly fast and competitive races, and the MIS facility (has) turned into a beehive of activity on race day with a rainbow of team tents and fans in an incredible atmosphere. Administratively, things (have) continued to get better every year.”

“I think we had close to 12,000 there this year at MIS” added Godefroidt. “If you try to put 10 or 12,000 on Washtenaw Country Club, there’s absolutely no way you could park everybody, there’s no way they all could see what they need to see.”

“The great side is everyone’s on the same course on the same day,” stated Kim Spalsbury, who coached boys and girls at Fowler and Grand Ledge over a 30-year span and has witnessed the event at MIS every year in some capacity. “From a coaching standpoint, you know the course, your kids have this institutional memory of the course because, if you have a good program or even if you just have had successful individuals, somebody on your team likely has been there before and experienced the race and can assure others of what it’s like. …That’s valuable to everybody to have that.

“And just from a historical perspective, the course might be a little different in terms of the conditions any given year; rain, cold … . It’s always tweaked a little bit here and there, but it’s essentially the same course and there’s all kinds of historical value in being able to compare times across generations now, you know, because we’re into a new generation since we started this in ‘96 down there.”

“What MIS does for us is just phenomenal, so it’s pretty hard to beat that site,” added Bork. “They are so professional there – the amenities that we have there that you wouldn’t have at any other place, it’s remarkable.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Special thanks to Chuck and Janet Janke, as well as those quoted in the article, for their assistance in telling the story.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

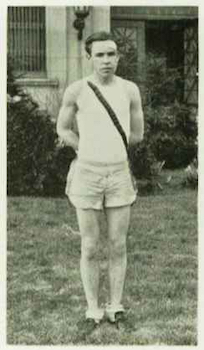

PHOTOS (Top) Contenders race during 1949 Finals at Washtenaw Country Club. (2) Jeff Hollobaugh’s book, XC! High School Cross Country In Michigan, is a detailed collection of the state’s cross country history. (3) Grand Rapids Central’s 1922 team featured Oscar Kutschinski, the first-place finisher in the state’s inaugural XC championships. (4) Ann Arbor’s 1924 championship team. (5) James Crummey of Iron Mountain. He would later run for the University of Wisconsin. (6) Fleet-footed Battle Creek Central ace Jim Arnold, two-time winner of the 1950 Class A XC meet. (7) Team photos of the 1971 XC champions. (8) Michigan International Speedway is the longtime home of the MHSAA Lower Peninsula Cross Country Finals. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)