Detroit's Goodfellows Game Pioneered Playing for Good Cause

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

August 31, 2021

Among the many benefits that come from a football game is the ability to use the gathering for the greater good.

Football games for charity are still played. In Michigan, Lowell High School is well known for its annual Pink Arrow game, created in 2008 to raise money and awareness for all types of cancer. Since that time, numerous schools across the state have done the same, bringing consciousness and much needed financial support to a variety of charities.

Beginning near the end of the 1930s, Detroit’s “Goodfellow Game” set the standard for such contests while becoming a classic of the Detroit sports landscape for 30 years.

The cast of characters fortunate enough to feel a connection to the game — students, coaches, and spectators — is impressive. But, with the final game played in 1967, and the passage of time, those with ties to the game are slowly disappearing.

The season-ending battle was built around a simple concept and became a huge fundraiser for the city’s “Goodfellow” organization, or Old Newsboys as they are often identified. Today, the group is perhaps best known for the yearly tradition of volunteers, stationed on city streets and street corners, selling special edition newspapers near the holiday. The Detroit edition of the organization was founded in 1914, and it still works to make sure no child is forgotten at Christmas.

Football and the Goodfellows

The connection between Detroit’s Goodfellows and football harkens back to at least Nov. 18, 1934, when, according to the book, “The Story of the Goodfellows,” written by Ernest P. Lajoie and published in 1938, “the Detroit Lions, a professional football team, staged a benefit game for the Old Newsboys” with the St. Louis Gunners.

George Albert Richards, radio station owner and the football club’s president, gave the charity the receipts from the game, played before 13,000 at University of Detroit stadium, then tacked on a personal check for an additional $1,000, “as a manifestation of his keen interest in the work of the Old Newsboys.”

George Albert Richards, radio station owner and the football club’s president, gave the charity the receipts from the game, played before 13,000 at University of Detroit stadium, then tacked on a personal check for an additional $1,000, “as a manifestation of his keen interest in the work of the Old Newsboys.”

The Kelly Bowl, played in Chicago and designed to raise money for charity, triggered the idea of mixing the fundraising efforts of the Goodfellow group with high school football. That game, first played in 1934 as well, “pitted the champion of Chicago’s public schools against that of the area’s Catholic League.” According to the Chicago Tribune, this “post-Thanksgiving match between private and public school squads was the only football game that really mattered at the end of the season.” Initially administered under the guidance of Mayor Edward J. Kelly, it was renamed the Prep Bowl during the 1940s.

An estimated crowd of 75,000 packed Soldier Field in 1936, and Detroit attempted to replicate the idea in 1937. Built around the concepts of “bragging rights” and civic pride, the contest would pit the champions of the Detroit Metropolitan League (later known as the City League and/or Public School League) and the Detroit Parochial League (or Catholic League). The winners, of course, could then legitimately call themselves Champions of Detroit.

A committee of the Old Newsboys, headed by Lajoie and two other past presidents of the group, pitched the idea to the officials of both high school leagues. The committee had hoped to arrange a contest between Detroit Catholic Central and Hamtramck high schools, “the only unbeaten or untied elevens in the metropolitan district.” According to the Detroit Free Press, it was estimated that with “favorable weather conditions, more than 15,000 would turn out for the contest.” However, the attempt failed when the committee was unable to get the idea past “Metropolitan League officials because of an iron-clad rule prohibiting post-season contests.”

The potential for good was far too great to drop the idea, so Detroit’s Goodfellow’s organization was back with its pitch in 1938. The Chicago game, according to reports, drew an unimaginable 120,000 football enthusiasts to the 1937 showdown, and this single game generated over $100,000 for the Windy City’s Christmas Fund, designed to help the needy. The colorful press clippings and imagery describing the contest and pageantry from the Chicago media must certainly have been impressive ammunition when arguing the case for trying to duplicate the concept.

In July 1938, Lajoie, representing the group, met with Frank Cody, superintendent of public schools; Rev. Father Carroll F. Deady, superintendent of schools in the Detroit archdiocese; and various other conferees, and he managed to successfully bring the parties together in agreement.

Detroit’s Goodfellow Game

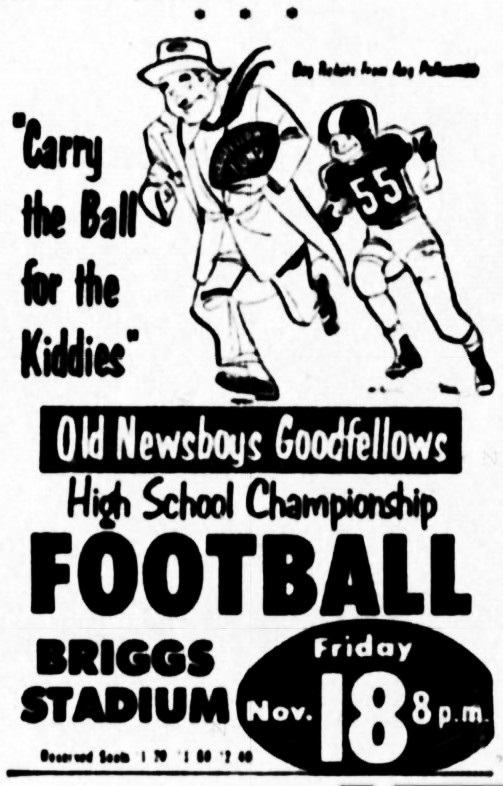

The contest would be “staged on the plan adopted in Chicago for the annual classic in Soldier Field” and feature the champions from the two leagues. Thanks to the generosity of Detroit Tigers owner Walter Briggs, the match-up was scheduled for play at Briggs Stadium, home to both the Major League Baseball Tigers and the National Football League Lions.

“Our aim is to make the meeting an annual one, on the same basis as the Chicago game,” said Lajoie. “(T)he title game is certain to become a sporting fixture in Detroit and one of the classics of the year.”

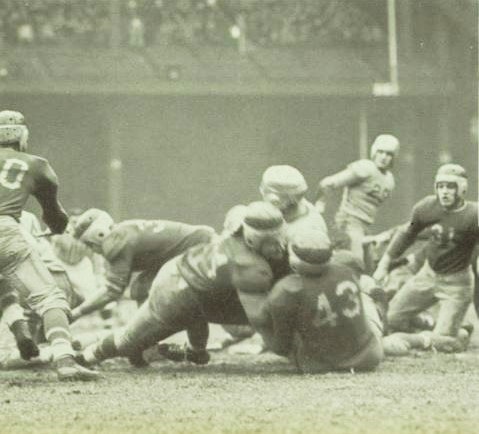

Scheduling conflicts within the two leagues in that first year meant the contest would have to be played after the normal end of the prep season. Because the Michigan High School Athletic Association regulation barred teams engaging in a game after Thanksgiving Day, special permission was needed to play. A waiver was granted, and on Saturday, Nov. 26, an announced crowd of 30,000—the most ever to watch a prep game in Michigan—gathered at Briggs Stadium for the showdown between heavily favored Hamtramck and Detroit Catholic Central. Special jerseys were ordered to add vivacity to the event.

The Cosmos “will wear blue sweaters with gold numerals, instead of (their normal) maroon with white numbers and (Catholic) Central players will sport gold jerseys with blue letters instead of blue with white,” noted the Detroit Times.

Both teams were again undefeated, with Catholic Central carrying a 25-game win streak into the game, while Hamtramck “a 3-1 favorite before the opening kickoff” carried an 18-game win streak into the contest. Players and fans were greeted by “falling snow and penetrating cold,” but the action on the field quickly cast the weather conditions aside.

The 19-13 victory by Detroit Catholic was, according to John Sabo of the Free Press, “the most spectacular and certainly the most interesting high school football game in Detroit history.

“Outplayed from the start from scrimmage, Catholic Central turned two intercepted passes and an end sweep into three long touchdown gallops which left the powerful Hamtramck team stunned almost before the game was underway.”

“All of Catholic Central’s scoring came in the first half,” noted Bob Murphy of the Times. “John McHale, Catholic Central’s center, supplied the first touchdown on a 52-yard gallop with an intercepted pass early in the game.”

The Cosmos blocked the extra point attempt then responded with their own 54-yard touchdown drive. With a successful point-after attempt, Hamtramck held a 7-6 lead.

Hamtramck had driven to the Shamrocks’ 11-yard line in the second quarter, before the game’s second pass attempt was snatched by 142-pound Rudy DeFrank, the “smallest back in the game,” who “streaked 97 yards down the sidelines to score.”

“The piece-de-resistance,” said Murphy, “was supplied by the swivel-hipped Tony Groth who cut through the heart of Hamtramck’s famed defense for 85 yards and a touchdown.” The score came in the last two minutes of the first half. The Shamrocks “only made one first down in the first half when it was running up its 19 points,” added the Free Press. With the win, Detroit Catholic made a claim to the state’s mythical state championship.

This inaugural battle for city bragging rights netted $22,000 for the Yuletide fund. The span between 1938 and 1967 was filled with thrillers (and a few blowouts) as the annual game generated “some $1.4 million (well in excess of $11 million in 2021 dollars) for the needy at Christmas time” during its run. The chase for the chance to play before a super-sized audience includes a roster of some of the greatest coaches and athletes in metro Detroit athletic prep history.

Goodfellows Game Grows

The 1939 interleague rivalry game, initially planned for Thanksgiving Day, was also a challenge to schedule and was one of two games in the series that were ultimately played in December. The newspapers in the days leading up to the contest between University of Detroit High and Detroit Catholic Central were filled with side stories, helping to build the pomp and circumstance that surrounded the affair. Tickets for the game were available for purchase at local bank branches, pharmacies, and retailers in a variety of locations, including establishments in Motor City architectural gems like the Penobscot Building and the General Motors Building (today known as Cadillac Place).

Biographies on the head coaches appeared in print. Hamtramck’s 114-piece band took on the halftime duties for U of D High, as the school did not have a marching band. Both U of D and DCC were all-boys schools. While Catholic Central High for Girls, a separate institution, aligned and cheered for the Shamrocks, there was no such association for U of D. According to the Times, female students from Detroit Cooley chose to adopt the team and cheer it on.

Biographies on the head coaches appeared in print. Hamtramck’s 114-piece band took on the halftime duties for U of D High, as the school did not have a marching band. Both U of D and DCC were all-boys schools. While Catholic Central High for Girls, a separate institution, aligned and cheered for the Shamrocks, there was no such association for U of D. According to the Times, female students from Detroit Cooley chose to adopt the team and cheer it on.

The University of Detroit High Cubs scored a 20-0 win over Detroit Catholic before 23,120 spectators. The victory ended the Shamrocks’ 34-game win streak that dated back to 1934.

Installation of a new drainage system at Briggs had prompted the need for a different location for the 1940 game. Detroit Cooley and Detroit St. Theresa finished in a 6-6 deadlock before a crowd of 14,861, in one of three Goodfellow games that was played at University of Detroit stadium, located at McNichols and Livernois at the northeast corner of the college campus. It marked the first of three ties contained within the results of the 30 contests.

Detroit’s Lions first played on Thanksgiving Day in 1934. However, with the NFL decision to avoid Thanksgiving Day contests between 1939 and 1944 due to World War II, and the MHSAA’s requirement that the football season end no later than that holiday, Goodfellow organizers took advantage of the opportunity. The 1941 game was moved back to Briggs with a scheduled 11 a.m. kickoff. The early start was selected so as to not interfere with traditional celebration dinners. Fire stations were added to the list of locations where tickets could be purchased.

The move was a roaring success, as a new record crowd of 30,714 fans showed up for a repeat of the 1940 match-up. The rematch was tight for the first half, with Cooley grabbing a 14-6 lead over St. Theresa at the break before the Cardinals blew it open, winning 47-6.

“The seven-touchdown parade that Cooley staged could not be considered an upset, and the score and the game’s statistics give a fairly accurate comparison of these two teams, both the tops in their own class, but definitely not in the same class,” said Marshall Dann in the Free Press.

Detroit Catholic Central won back-to-back titles in 1942 and 1943. The ’42 contest, the second, and last, played on Thanksgiving, was a 46-0 mismatch with Hamtramck. The ’43 game, moved back to U of D Stadium due to a pre-scheduled reconditioning at Briggs Stadium, was an 8-0 surprise victory upset over Cooley. Two long spiraling kicks by DCC’s Ed Burgess pinned Cooley deep inside its 10-yard line, leading to Shamrock scores. In comparison to previous years, the reduced crowd of 17,500 spectators was a disappointment.

In the week prior to the game, LaJoie had noted that tickets sales were moving slowly. Underscoring this area of concern was the fact that the Kelly Bowl game in Chicago, played on the same day, attracted 80,000 fans. Detroit News sports editor H.G. Salsinger expressed his opinion that proper promotion of the game by organizers in Detroit was at fault. Other sportswriters concurred.

“What is needed, noted the Free Press, is a group of workers of the type of the New Orleans Sugar Bowl Committee, who will devote time and energy to putting across not only the sale of tickets but the staging of the game as a civic proposition.”

Locally, citizens responded, and for the 1944 match-up, refocused efforts were made to ensure success of the game’s amazing ability to raise significant funds earmarked for the greater good. The Detroit Police Department took over the sale of tickets, improving distribution. Tickets could still be purchased at various locations throughout the city, but now, under the direction of Senior Inspector Samuel J. Throop, they could also be bought directly from any police officer.

The game that fall was moved back to Briggs and dedicated to the memories of four former Goodfellow Game stars, each who had given their lives while serving in World War II. In a battle of previously unbeaten squads, a 13-yard field goal in the last 18 seconds of play by Jerry Wood gave Detroit Mackenzie High a nail-biting 3-0 victory over Holy Redeemer before a throng of 30,054 onlookers.

“Although beaten, Redeemer staged one of the most courageous battles ever witnessed in Briggs Stadium. Four times the Lions halted the Stag’s offensives inside their 15-yard line,” noted the Free Press. It was Wood’s first field goal attempt on the season, although his accuracy on extra points earlier in the year had ensured two other Mackenzie wins.

The public schools won three in a row between 1946 and 1948, including two consecutive by Detroit Denby. A record crowd of 39,004 was on hand for the 1948 game at Briggs, the first played at night on a Friday, when Denby trounced St. Mary’s of Redford, 28-0.

U of D fumbles set up an upset 19-13 victory by East Side underdog St. Anthony in 1949 before 34,038.

Power Begins to Swing

During the 10-game span of the ’50s, the right to brag was equally divided.

In 1950, Detroit Redford squeezed out a 7-6 public school win over little Detroit St. Gregory. The single point win would stand as the thinnest margin of victory in the three-decade run of games.

“I’m sure that at the end most of the fans wished there was no such thing as the extra point in football,” wrote Murphy, now sports editor of the Times. “St. Gregory deserved a tie.”

“I’m sure that at the end most of the fans wished there was no such thing as the extra point in football,” wrote Murphy, now sports editor of the Times. “St. Gregory deserved a tie.”

A few days later, a true list of Detroit sports legends attended the annual football bust designed to honor members of both teams.

“The Big Guys paid the Little Guys a visit Tuesday night,” said Hal Schram of the Free Press. “Never before in the 13-year history of the event have so many guest stars attended. “Doak Walker, Leon Hart, Thurman McGraw, Jack Adams, Red Kelly, Gordie Howe, Ted Lindsay, Ted Gray, Harry Heilmann and Bo McMillin all took a bow while several offered brief congratulations.”

Van Patrick, sports director for radio station WJR and play-by-play man for the Tigers and Lions, served as toastmaster.

The St. Mary’s Rustics of Redford, coached by Al Chesney, won consecutive games in ’51 and ’52, then the public schools won three straight between 1953 and 1955.

“The slashing runs of halfback Fred Julian, Pershing High’s finest back since the days of Harry Szulborski (Purdue), enabled the Doughboys to claim their second City football championship in three years,” Schram told his readers in 1955. “Julian scored one touchdown — a brilliant 57-yard spring — and set up the other as Pershing conquered St. Mary of Redford, 13-7 before 29,830 fans in Briggs Stadium Friday night.”

(Julian would later play at the University of Michigan, then for a year in the American Football League for the New York Titans. As head football coach at Grand Rapids West Catholic for 16 years, he guided his team to the MHSAA Class B runner-up finish in 1979.)

Closer Look

Further examination shows that between 1946 and 1955, the City League won seven of 10 games. But as the parochial schools began to draw in more students from across the metro area, fortunes started to shift. The arrival of the 1956 season saw Detroit DeLaSalle down Denby, 26-20. The next 12 years illustrated the growing strength of the Detroit Catholic League in metro Detroit as parochial squads won eight of those showdowns, against three for the city league teams. One game, the 1965 match between Harper Woods Notre Dame and Denby, ended in a 14-14 deadlock.

Coach Dan Boisture of St. Mary of Redford and his younger brother, Tom, coach at little Grosse Pointe St. Ambrose, showcased their coaching chops in the Catholic League and before huge audiences in the Goodfellows Game. (Dan would later assist head coach Duffy Daugherty at Michigan State, then guide Eastern Michigan University’s gridiron squad for seven seasons. Tom would coach at Holy Cross before moving on to the NFL, first as a scout for the New England Patriots, then as director of player personnel for the New York Giants.)

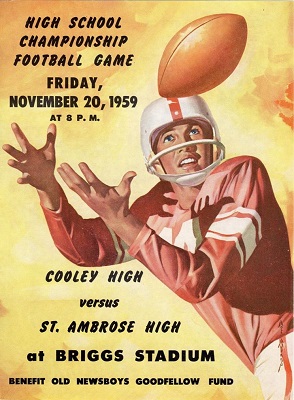

Dan guided St. Mary of Redford to four of five Goodfellow Games, between 1954 and 1958, defeating Southeastern in 1957. Tom led St. Ambrose to, arguably, the greatest upset in the series in 1959, when his team took down top-ranked Cooley behind the running of Joe D’Angelo.

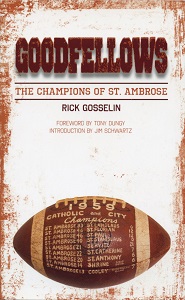

Tied 7-7 with less than 90 seconds remaining, the 5-foot-6, 150-pound “streak of lightening” took a fourth down handoff and “ducked into a “cluster of humanity,” wrote Rick Gosselin in his 2009 book, Goodfellows: The Champions of St. Ambrose.

Seemingly stopped at the line of scrimmage by three Cooley linemen — or was it four — D’Angelo kept his feet moving and “squirted loose.” In the play of the game, his 22-yard run gave the Cavaliers a stunning 13-7 lead.

Seemingly stopped at the line of scrimmage by three Cooley linemen — or was it four — D’Angelo kept his feet moving and “squirted loose.” In the play of the game, his 22-yard run gave the Cavaliers a stunning 13-7 lead.

“Cooley would get the ball back with 1:20 remaining,” Gosselin continued. “But like St. Ambrose, the Cardinals were built to win games by running the football, not throwing it. … The biggest upset in Goodfellow history was sealed.”

(D’Angelo would later coach teams at St. Ambrose and Erie Mason, win two MHSAA football titles at Detroit Country Day, then finished his career at Birmingham Hills Cranbrook Kingswood. He retired with 239 victories.)

Gosselin, who graduated from St. Ambrose and Michigan State University and has covered the NFL for 49 years for some of the nation’s largest media outlets, recaps the story of the school without a home field succinctly in Chapter 1 of his publication:

“Over a nine-year period from 1959 through 1967, the Cavaliers would post a 64-8-3 record, winning six conference titles, five Catholic League titles with a perfect 5-0 record in Goodfellow Games, and four state championships. Little St Ambrose would enjoy four 9-0 seasons during that stretch with two other seasons ending with a single loss.”

The 1960 battle at Briggs, a 21-18 come-from-behind victory by Denby over Catholic Central, featured an all-time Goodfellow attendance record of 39,196.

St. Ambrose won consecutive titles in 1961 and 1962 with a pair of shutout victories. Tom Boisture’s ’61 team downed Pershing, 20-0. Boisture’s replacement as coach for the 1962 season was George Perles, who had played in the 1951 game for Detroit Western and would later guide Michigan State’s football squad. Perles guided the team to triumph, 19-0 over Cooley. Each game hosted at the ballpark located at Michigan and Trumbull — by then named Tiger Stadium — drew over 37,000. The 1962 game marked the sixth in a row in which attendance exceeded 30,000.

TV & Tragedy

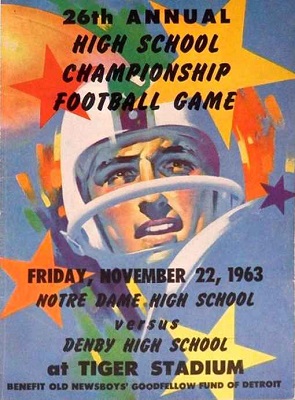

In 1963, a pair of teams with 6-1 records squared off in the Soup Bowl — the nickname for the Catholic League championship game — for their first-ever chance to play in the Goodfellow Game. Harper Woods Notre Dame and Royal Oak Shrine battled for 48 minutes to a scoreless tie before 17,500 fans at U of D. To determine a winner, league rules awarded the game to the team with the greatest yardage gained. Over the game’s final minute and 26 seconds, Notre Dame had picked up 21 yards during the final series of downs and finished with 163 yards to Shrine’s 159. Hence the Irish scored a “four-yard victory” over the Knights.

One week later, Denby dumped Cooley, the No. 1-ranked team in the state according to the Free Press, 26-13, in the 1963 public school championship game played before another crowd of 17,500 at U of D to earn its third trip to the Goodfellow Game in eight years.

This time, plans were made for a television broadcast of the City Championship game. Game chairman I.A. Capizzi said he didn’t know what effect televising the game might have on gross receipts, but he thought the experiment made sense. WWJ-Channel 4 in Detroit was cancelling the airing of the Bob Hope show and planned to air a 30-minute pregame show, which would “carry the (Goodfellow’s) message of charity work to thousands of viewers.” The hope was that loss in attendance at the gate would be minimal, and that the group might see an increase in revenue during the annual Goodfellow newspaper sales on the streets of Detroit.

This time, plans were made for a television broadcast of the City Championship game. Game chairman I.A. Capizzi said he didn’t know what effect televising the game might have on gross receipts, but he thought the experiment made sense. WWJ-Channel 4 in Detroit was cancelling the airing of the Bob Hope show and planned to air a 30-minute pregame show, which would “carry the (Goodfellow’s) message of charity work to thousands of viewers.” The hope was that loss in attendance at the gate would be minimal, and that the group might see an increase in revenue during the annual Goodfellow newspaper sales on the streets of Detroit.

The transmission would certainly bring the organization’s message before a new audience. Unfortunately, the impact of the test would not be known. Events of the day meant the broadcast would be cancelled.

At 1:30 p.m. Michigan time on November 22 — the scheduled day of the 26th Goodfellow Game — President John F. Kennedy was killed while riding in a motorcade in Dallas. Goodfellow officials, faced with an immediate decision, considered rescheduling, but the contest went on as planned, “in spite of the national tragedy.”

At 1:30 p.m. Michigan time on November 22 — the scheduled day of the 26th Goodfellow Game — President John F. Kennedy was killed while riding in a motorcade in Dallas. Goodfellow officials, faced with an immediate decision, considered rescheduling, but the contest went on as planned, “in spite of the national tragedy.”

“The purpose of the game is to provide help for needy children,” Capizzi told the media. “(C)anceling it would have deprived thousands of these children of a visit from Santa. We believe President Kennedy would have concurred in the decision since he held so much love for humanity, especially little children.”

“Both schools also decided it would be unfair to ticket holders to cancel on such notice,” added the Free Press.

To no surprise, attendance suffered with a crowd of 23,500 reported.

Denby won the game, 7-0, beneath a cloud of sorrow as a light rain fell. The win was the Tars’ ninth on the year and 36th in the previous 37 games. With the victory and a No. 1 ranking by the Free Press, they staked a claim on the state’s Class A mythical title.

Attendance Sinks

Fundraising took another hit in 1964. The game, played on a sloppy, slippery Tiger Stadium field, was scheduled for a Thursday night — a school night — as the National Football League restricted use of the field based on the days before a Lions game. Adding to the challenges, a newspaper strike affected publicity for the game. And, this time, the game was televised.

“Only 15,104 fans braved the winter’s first measurable snow (a blizzard) to see St. Ambrose beat Southeastern, 20-0, the smallest crowd ever, the worst weather ever,” reported the Free Press. “(Cavalier Coach) Perles had a nine-inch television monitor at the sidelines. ‘All I could see was snow — on the set and on the field,’ Perles laughed.”

“Television gave us a half hour (before the broadcast) to tell the history of the Goodfellows and their work at Christmas,” noted the group. This time, there was no need for crunching numbers. There was little question that the airing of the game hurt attendance.

Reported gross income of $63,000 from the contest was off significantly from the past averages of $75,000-$80,000. St. Ambrose’s fourth appearance in six years, combined with its fourth victory over City League competition, prompted conversation about adding suburban schools into the mix when determining teams that would meet the parochial champion.

“Extensive grade school, even freshman and reserve programs, give the Catholic League a decided superiority the City League can’t match,” said Dr. Robert Luby, Health and Physical Education Supervisor of the Detroit Public Schools to the Free Press, discussing possible solutions to sagging interest in the game. “(M)aybe it would help to allow suburban schools to take part in the championship."

The crowd was back up above 25,000 for the 1965 game, a 14-14 stalemate between Denby and Harper Woods Notre Dame played on a Friday night. Officials looked at playing the 1966 game on a Saturday night at Tiger Stadium, however NFL requirements related to prepping the stadium before a Detroit Lions game again created challenges. When combined with the fact that the Detroit Board of Education had banned night football because of rowdyism and disturbances, the contest was moved back to the University of Detroit and scheduled with a 10:30 a.m. kickoff Saturday, Nov. 19. The early start was designed to avoid competition with the Michigan State-Notre Dame game scheduled for 1:30 p.m.

The crowd was back up above 25,000 for the 1965 game, a 14-14 stalemate between Denby and Harper Woods Notre Dame played on a Friday night. Officials looked at playing the 1966 game on a Saturday night at Tiger Stadium, however NFL requirements related to prepping the stadium before a Detroit Lions game again created challenges. When combined with the fact that the Detroit Board of Education had banned night football because of rowdyism and disturbances, the contest was moved back to the University of Detroit and scheduled with a 10:30 a.m. kickoff Saturday, Nov. 19. The early start was designed to avoid competition with the Michigan State-Notre Dame game scheduled for 1:30 p.m.

“There would be little sense … to try to compete,” said a spokesman. “(Otherwise) we would probably wind up with 20 people.”

As it turned out, only 12,337 fans showed up — less than half the crowd size from the year previous — to watch St. Ambrose win its fifth city championship, 33-19 over Denby. With the triumph, the series was now evenly split, with 13 wins for each league against three tie ballgames.

Reduced costs meant the charity still netted around $45,000, but it was a fraction of past years.

Goodfellow Game’s Clock Hits 0:00

“With Michigan, Michigan State, the Lions, the Red Wings and the Pistons playing away this weekend,” stated the Free Press, “the Denby-Divine Child struggle in the (30th) annual Goodfellow game at Tiger Stadium rates as the top local attraction."

“The game lived up to advance predictions of a knockout,” wrote another newspaper.

Tied 7-7 at the half, a costly fumble gave Dearborn Divine Child a 14-7 upset of Denby. Ed Puishes, the Falcons’ all-state back, scored Divine Child’s first touchdown and would go on to play at the University of Texas at El Paso. Divine Child’s Gary Danielson, a future NFL quarterback, scored the game’s last TD on an eight-yard rollout midway through the third quarter.

Despite the return to the large facility, and a strong matchup, only 15,186 made the trip to Detroit’s Corktown neighborhood. In August 1968, officials announced the end of the annual contest. Sagging interest and attendance figures were mentioned at the forefront, but Free Press coverage also stated that athletic directors from both leagues had “long urged that the game be dropped since it impressed a harsh handicap in scheduling for the entire season.”

Difficulty controlling crowds in recent years was also cited as a concern.

Occasionally, conversations surface about resurrecting the game, but times have changed. With the consolidations and closings of schools within both the Catholic parishes and the Detroit Public School system, the establishment of the MHSAA football postseason, and the influences of Michigan’s school of choice program, it would be nearly impossible to recreate.

Still, the impact of the game on the lives of those who participated in the game, as well as the lives of those who saw Christmas boosted by the work of the Goodfellows, should always be remembered.

The MHSAA is always on the lookout for memorabilia from Michigan’s school sports past. Please contact historian Ron Pesch at the email address below if you have photos, programs, trophies or similar items you’d like to share or donate.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) Members of the Detroit Redford and St. Gregory teams receive their trophies after Redford’s 1950 Goodfellows Game win. (2) The Old Newsboys’ Ernest P. Lajoie sells newspapers on the streets of Detroit. (3) University of Detroit High plays to a 20-0 win over Detroit Catholic Central in 1939. (4) The Detroit Tribune advertises the 1955 Goodfellows game. (5) The 1956 trophy was set to split the year between schools after Denby and Notre Dame tied. (6) The 1959 and 1963 programs reflect the name change at the Goodfellow Games’ home field, Briggs Stadium-turned-Tiger Stadium. (7) Nationally-acclaimed journalist Rick Gosselin tells the Goodfellows story of his alma mater. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch with courtesy to the Detroit Tribune and local yearbooks.)

Memories Don't Fade for 1st MHSAA Class A Champion Franklin

By

Brad Emons

Special for MHSAA.com

November 8, 2024

Even after 50 years, Tim Hollandsworth recalls Livonia Franklin’s run to the first MHSAA Class A football playoff championship like it was yesterday.

Before 5,506 fans at Western Michigan University’s Waldo Stadium, the unranked Patriots capped a season for the ages by upending heavily favored Traverse City for the 1975 title, 21-7.

“It was a once in a lifetime event, and I guess it just brings back great feelings winning that game obviously,” said Hollandsworth, who went on to become an all-Mid-American Conference linebacker at Central Michigan. “What I remember most was carrying that trophy around on the field. Myself, Jim Casey and the whole team ... we paraded it out Stanley Cup-style in front of our fans, and everybody was going crazy. Just a happy time.”

The championship game was played on a frigid Nov. 22 afternoon in Kalamazoo, just 12 years following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

“When I think about that game, the first thing that comes to mind is that it was a cold, cloudy day before the game,” Hollandsworth said. “And as the game started, the sun came out; it was really bright. It turned out to be a bright, sunny day, and we didn’t feel the cold at all. The adrenalin was pumping.”

No. 2-ranked Traverse City, coached by Jim Ooley, entered with a high-powered offense averaging 34 points per game. The Trojans featured the running back tandem of Rick Waters (1,300 yards) and Bruce McLachlan, along with tight end Mark Brammer, a two-time All-American at Michigan State who later played five seasons for the Buffalo Bills in the NFL.

Franklin took a 7-0 lead in the first quarter when Dennis Smith, the holder on a 30-yard field goal attempt by Sam Williams, couldn’t secure the snap from center but alertly got up and tossed a 17-yard TD pass to Rick Lee.

The Patriots then went up 14-0 in the second quarter on a 3-yard TD run by Casey, who went on to play four seasons at Ball State as a defensive back.

Traverse City cut the deficit to 14-7 before halftime on a 2-yard TD run by McLachlan, but the Patriots put it away in the final quarter on a 9-yard TD run by Casey, who finished the game with a hard-earned 105 yards on 24 carries.

Hollandsworth, who also starred in the backfield with Casey, severely twisted his ankle in the first half and was limited to playing only defense for the remainder of the game. Fortunately for Franklin, Tom Smith took his place and helped continue the offensive surge.

“It was just the fact that everybody was just stepping up when they had to have them,” Casey said. “I think it kind of exemplified everything we did throughout the year to get there. That’s what was so cool about the whole deal.”

“It was just the fact that everybody was just stepping up when they had to have them,” Casey said. “I think it kind of exemplified everything we did throughout the year to get there. That’s what was so cool about the whole deal.”

Meanwhile, Waters – who later became Hollandsworth’s friend and teammate at CMU – led the Trojans’ rushing attack with 85 yards rushing on 19 carries.

Franklin’s defense played a pivotal role in the win with four interceptions – one each by Hollandsworth, Chuck Hench, Jerry Pollard and Casey (his 10th of the season).

Williams, the Patriots’ star tight end and middle linebacker and the son of former Detroit Lions “Fearsome Foursome” defensive end Sam Williams Sr., also batted down a key fourth-down pass in the end zone to thwart a Traverse City scoring threat.

“It’s funny about the whole game ... you forget about the details, it’s crazy,” Casey said. “It was everybody coming together. There may have been some mistakes along the way. That just happens during the game and we hung in there, did what it took to score enough points to win.”

The game was played on artificial turf, not real grass, which was also a first for both teams.

“I think it had been raining the day before ... anyhow, the field was soaked,” Casey said. “And all it takes is to fall on a field that is soaked on an Astroturf field and everything, and all your clothes are soaked. I remember in the first half – I couldn’t wait for halftime to go inside and warm up.”

During the practice week prior to the title game, the Patriots were able to get acclimated when athletic director and assistant coach George Lovich made a deal to practice on the University of Michigan’s artificial surface.

“We had to get new shoes because nobody had played on artificial turf in high school back then,” Casey said. “They had a bunch of used shoes from the (U-M) team. They threw them in a big old box and they let us practice one night on their Astroturf. We went in and got our shoes and we were ready to play – excited about that. It was just different compared to regular grass. It felt super-fast.”

With only four spots per Class up for grabs in the inaugural MHSAA playoffs, five unbeaten Class A teams did not make the postseason including Warren Fitzgerald and Mount Clemens Chippewa Valley from Region 1, Trenton in Region 3, and Grand Rapids Union and Marquette from Region 4.

On the final Saturday of the regular season at Eastern Michigan’s Rynearson Stadium, No. 1-ranked Birmingham Brother Rice (Region 2) was upset in the Catholic League championship, 7-0, by Dearborn Divine Child, which went on to claim the Class B title.

That allowed the 8-1 Patriots, who had lost to rival Livonia Stevenson 13-9 in Week 2, to sneak into the playoffs just ahead of the previously-unbeaten Warriors.

“We were all in the stands watching that game,” Hollandsworth said. “And our coach, Armand Vigna, had all our points figured out right to the point where he said if Brother Rice were to lose, we were in. So, we’re sitting in the stands and Detroit Southwestern is off to our right a little bit higher in the stands. When Divine Child won that game, we were just going crazy and you could see Southwestern wondering who we were and what was going on.”

During the build-up to the Class A Semifinal game against Franklin, Southwestern coach Joe Hoskins was quoted in the Detroit newspapers as saying, “Livonia who?”

Southwestern was led by all-state QB Mike Marshall (MSU), along with junior tackle Luis Sharpe (UCLA), an eventual first-round NFL pick who played 13 seasons with the St. Louis, Phoenix and Arizona Cardinals.

And in that Semifinal at Pontiac’s Wisner Stadium before 5,000 fans, Franklin upended the No. 3-ranked Prospectors, 12-9, as Casey ran for 145 yards on 27 carries. Hollandsworth added a 1-yard TD to cap a nine-play, 72-yard drive and give his team the lead 9-7 at the half.

Southwestern got an 18-yard TD pass from Marshall to Andrew Williams and scored on a two-point safety when the Patriots fumbled the kickoff to start the second half.

Williams, however, booted a pair of field goals, including the game-winning 28-yarder to break a 9-9 deadlock for the Patriots after they were aided by a pass interference call followed by an unsportsmanlike conduct penalty, which took the ball to the Southwestern 18.

In protest, Hoskins took his team off the field and had to be coaxed by MHSAA officials to bring his players back to finish the game.

“I think we were excited about the playoffs because we were undefeated the year before, so were looking forward to getting into the playoffs,” Hollandsworth said. “It was deflating when we lost; it was low-scoring, tough battle versus Stevenson. All the Livonia games (vs. Churchill and Bentley) were tough battles. It was the first game that Sam Williams was out. He got hurt in the (Dearborn) Fordson game before that (the opener) and Sam was not only our tight end, and starting middle linebacker, but he was also our punter and kicker. I think we passed up some field goals in that Stevenson game because we were so unsure of our kicking game.”

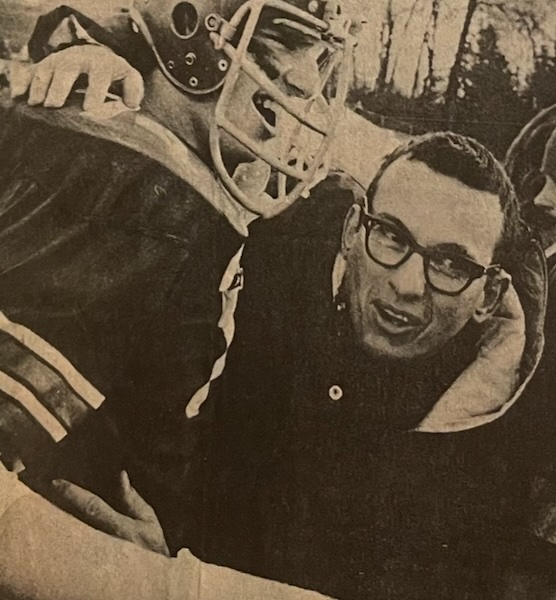

PHOTOS (Top) Livonia Franklin’s Jim Casey (45) plows ahead during the 1975 Class A Final as Traverse City tacklers converge. (Middle) Franklin coach Armand Vigna, right, shares an embrace with lineman Rick Kruger in the moments after their team’s championship victory. (Photos courtesy of Hometown Life, which includes the former Livonia Observer).