'Over Here,' Athletes Gave to WWI Effort

March 28, 2018

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

In a nation at war, the needs of many outweigh the desires of a few.

Among the many noble sacrifices for the greater good was Michigan’s spring high school sports season of 1918.

The United States’ entry into “The Great War” (today commonly known as World War I) came on April 6, 1917, 2½ years after the war had begun. First elected President of the United States in 1912, Woodrow Wilson earned re-election in 1916 under a platform to keep the U.S. out of the war in Europe. The sinking of the British passenger ships Arabic and Lusitania in 1915 caused the death of 131 America citizens, but did not invoke entry into the conflict. However, continued aggressive German actions forced a reversal in policy.

“The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind,” stated Wilson in an April 2 special session of Congress, in requesting action to enter the war.

A huge baseball fan, President Wilson recognized the value of entertainment and athletics during a time of crisis. Major league baseball, America’s pastime, completed a full schedule in 1917. A former president at Princeton University, on May 21, 1917, Wilson addressed the value of school athletics in a letter to the New York Evening Post.

“I would be sincerely sorry to see the men and boys in our colleges and schools give up their athletic sports and I hope most sincerely that the normal courses of college sports will be continued so far as possible, not only to afford a diversion to the American people in the days to come when we shall no doubt have our share of mental depression, but as a real contribution to the national defense. Our young men must be made physically fit in order that later they may take the place of those who are now of military age and exhibit the vigor and alertness which we are proud to believe to be characteristic of our young men.”

“I would be sincerely sorry to see the men and boys in our colleges and schools give up their athletic sports and I hope most sincerely that the normal courses of college sports will be continued so far as possible, not only to afford a diversion to the American people in the days to come when we shall no doubt have our share of mental depression, but as a real contribution to the national defense. Our young men must be made physically fit in order that later they may take the place of those who are now of military age and exhibit the vigor and alertness which we are proud to believe to be characteristic of our young men.”

Despite the highest of hopes, the requirements and realities of war deeply impacted life in the U.S. soon after.

In February of 1918, a proposal was circulated by Dr. John Remsen Bishop, principal of Detroit Eastern High School and president of the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association, to abolish spring athletics at Michigan high schools. Due to a labor shortage brought on by the war, the states, including Michigan, needed help on farms, harvesting crops from spring until late fall. The action might also affect the football season of 1918.

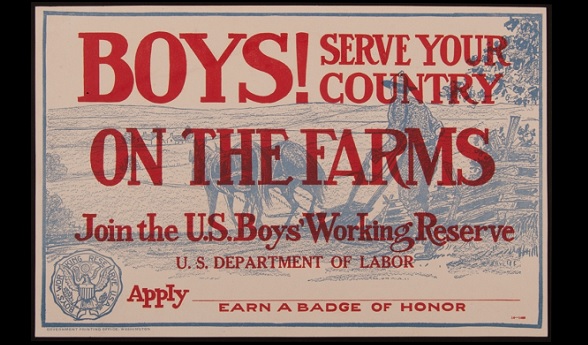

The Boys’ Working Reserve, a branch of the U.S. Department of Labor, was organized in the spring of 1917 and designed to tap into an underutilized resource to help address that labor deficiency. “Its object was the organization of the boy-power of the nation for work on the farms during the school vacation months.”

While the idea was popular among schools around Detroit, due to the lack of public commentary from outstate school administration, it was expected that the proposal would meet at least some opposition when the M.I.A.A. gathered on Thursday, March 28 in Ann Arbor during a meeting of the state’s Schoolmasters Club.

Less than two weeks prior to the March meeting, Michigan Agricultural College made an announcement that would impact one aspect of the coming spring sports season.

“The department of athletics of the Michigan Agricultural College begs to inform the high schools of the state that plans for the annual interscholastic track meet, which was to have been conducted here in June, have been given up this year – not through any desire on the part of this department to discourage athletics, but because this is a time when we can and should devote our resources to better uses,” said coach Chester L. Brewer of the Aggies to the Lansing State Journal. “It would hardly be sound judgment for us to make our usual elaborate plans for this meet while our government is appealing to all of us to economize and exercise the utmost thrift. Neither is it wise policy to encourage unnecessary traveling upon the railroads, or to ask high schools of the state to make any expenditures other than those which are absolutely necessary.”

Earlier in the year, similar news had come from the University of Michigan.

In January of 1917, the University of Michigan had announced plans for an elaborate annual high school basketball invitational, designed to identify a Class A state champion. Billed as the “First Annual Interscholastic Basket Ball Tournament,” the March event hosted 38 teams. However, influenced by the war, a decision had been made not to run a second tournament in 1918. Instead, on March 27, Kalamazoo Central and Detroit Central, two of the state’s top teams, were invited to Ann Arbor for a hastily arranged contest at U-M’s Waterman Gymnasium. The schools had split a two-game series during the regular season. Kalamazoo won the season’s third matchup, and while not official, declared itself 1918 Michigan state champion.

Into this environment of patriotism and uncertainty, school administrators arrived in Ann Arbor for the Schoolmasters gathering. There, in the morning, the membership heard a presentation from H. W. Wells, assistant and first director of the Boys’ Working Reserve. “The heart of the nation, rather than the hearts of the nation, is beginning to beat. War is making us a unit,” said Wells, discussing the aim to recruit boys between the ages of 16 and 21 to help provide food for the allies in Europe and at home in the United States.

“Wells told of the need for the farmers to sow more wheat, and plant more corn,” reported the Ann Arbor News, “and in the same breath he told of great corn fields all over the country, where last year’s corn still lay unhusked, because of a lack of farm labor.”

“Wells told of the need for the farmers to sow more wheat, and plant more corn,” reported the Ann Arbor News, “and in the same breath he told of great corn fields all over the country, where last year’s corn still lay unhusked, because of a lack of farm labor.”

It was estimated that 25 percent of the nation’s farm workforce was now active in the armed forces.

The proposition was brought to the M.I.A.A. by Lewis L. Forsythe, principal at Ann Arbor High School, who would soon establish himself as a guiding force in high school athletics. The proposal “was discussed thoroughly.”

“This session is usually a stormy one, because of contentions that arise over rulings that affect schools in different ways,” said Adrian superintendent Carl H. Griffey to the Adrian Daily Telegram, “but this meeting was a serious one in which all matters were related to our national welfare and passed by unanimous votes.”

So, one day after the conclusion of the abbreviated state basketball championship contest, the spring prep sports season in Michigan came to an abrupt halt. Michigan’s male high school students were asked to work to support the war effort.

“Chances are that they will remain there for the duration of the war,” stated the Lansing State Journal in response to the action. “At the meeting … it was talked of quitting football because of the need of the boys staying on the farms till the latter part of November. This is highly probable. If it is passed upon then Michigan high schools will have but one sport, basketball.

“Whether intra-mural sports will replace the representative teams is not known. This form of athletics demands the attention of a great number of teachers to tutor the different class organizations. The teachers are taxed to the limit at present and cannot give the time to sports. Organizing farm classes and Liberty bond teams is taking the teacher’s spare moments. … But still athletics are needed, as the war has demonstrated, and physical training should be instituted from the kindergarten to the university.“

“Those lads who leave for the farms the first of May,” wrote the Port Huron Times-Herald, “will be in better condition when they return home from the fields and cow lanes than they would (have) had they remained in the city until June batting the leather pill.”

The fate of the 1918 football season would not be known until late August.

In late June, the 29th Governor of Michigan, Albert E. Sleeper, thanked the estimated 8,000 students who had joined the ranks.

“To you soldiers of the soil I would say this, that I am as proud to address you as I would be to address any of the boys who are bearing arms for their country. You have proved that you are true patriots, for you have started out to do exactly what your country has asked you to do – the thing which you can do best for your country at this time.

“To you soldiers of the soil I would say this, that I am as proud to address you as I would be to address any of the boys who are bearing arms for their country. You have proved that you are true patriots, for you have started out to do exactly what your country has asked you to do – the thing which you can do best for your country at this time.

“Every day, in the rush of official work, I think of you Reservists as you work on the farms, just as I think of our soldiers who are in training camps or ‘over there.’ And I am just as proud of you as I am of them. So are all the people of Michigan.”

It was estimated “the boys who last spring left their high school studies and as members of the United States Boys’ Reserve have helped the Michigan division to add $7,000,000 to the food production of the nation.”

In September, Byron J. Rivett, secretary of the M.I.A.A., announced that, based on a vote of member high schools, prep sports would be resumed in the fall. The Detroit News celebrated the news that “moleskins and pigskins will be in evidence and the grand old game will be a part of the autumn’s entertainment.”

In October, in Grand Rapids and Detroit and other cities across the state, officials gathered to honor those who served as part of the “Michigan Division of the Reserve” and to award bronze badges in recognition for their contribution to the war effort.

World War I officially ended on November 11 with the signing of the armistice. Armistice Day, today known as Veteran’s Day, was first celebrated in 1919. In total, an estimated 16 million were killed during the war.

“Four million ‘Doughboys’ had served in the United States Army with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Half of those participated overseas,” said Mitchell Yockelson in Prologue magazine, a publication of the National Archive. “Although the United States participated in the conflict for less than two years, it was a costly event. More than 100,000 Americans lost their lives during this period.”

More than 5,000 of those casualties had come from Michigan.

***

To the surprise of the world, a second war arrived in 1918. This one did not discriminate based on geographic or political borders. It would take more lives than World War I.

To the surprise of the world, a second war arrived in 1918. This one did not discriminate based on geographic or political borders. It would take more lives than World War I.

Globally, the Spanish Flu pandemic arrived in three waves, one in the spring, one in the fall of 1918, and a third arriving in the winter of 1919 and ending in the spring. It, too, would impact high school and college athletics in Michigan and beyond, as countless football games across the nation were cancelled in an attempt to help reduce the spread of the disease.

In the end, an estimated 675,000 would die in the United States from the virus. In Michigan, hundreds succumbed in October 1918 alone. In Detroit, between the beginning of October and the end of November, “there were 18,066 cases of influenza reported to Detroit’s Department of Health. Of these, 1,688 died from influenza or its complications.” Worldwide, an estimated 50 million were killed by the Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) The U.S. Department of Labor recruited high school students to work on farms as soldiers went oversees to fight World War I. (Middle top) A Working Reserve badge. (Middle) Lewis L. Forsythe. (Below) Another recruitment poster for the Working Reserve shows a man plowing a field while war rages in the background. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)

Machiniak Sets Pace as Berrien Springs Edges Corunna in Matchup of Recent Champs

By

Scott DeCamp

Special for MHSAA.com

June 1, 2024

HAMILTON – After a rainy afternoon Saturday, the precipitation let up long enough for Berrien Springs’ boys track & field team to put the finishing touches on another MHSAA Lower Peninsula Division 2 Finals championship.

After Shamrocks head coach Jon Rodriquez collected his program’s second team title in three years, rain fell again at Hamilton High School’s Hawkeye Stadium, only heavier this time.

The reign returned for Berrien Springs.

“It feels great, man. It’s hard to say what it feels like,” said Shamrocks senior standout Jake Machiniak, who sprinted to first-place finishes in the 100- and 200-meter dashes plus anchored winning 400 and 800 relays.

“This team, they worked all offseason. This is the hardest group of workers I’ve ever had. All these guys, all the guys that scored, they’ve all come year-round. The relays, we performed. I performed in the opens. It’s great. It’s a great feeling, man. Two times, man. Two times. Second time winning the state. It’s fantastic, man.”

Machiniak, a Grand Valley State University commit, repeated in the 100 with a time of 10.74 seconds. He won the 200 in 21.76 seconds in addition to running the closing leg on Berrien Springs’ first-place 400 relay (42.13) and victorious 800 relay (1:28.24).

Machiniak powered Berrien Springs to 40 points as a team, allowing the Shamrocks to edge runner-up Corunna (38 points), the 2023 champion. DeWitt was third (34) and Charlotte fourth (28), followed by Pontiac Notre Dame Prep and Parma Western tied at fifth (26).

Last year, Berrien Springs tied for seventh, which fueled the Shamrocks’ hunger all offseason.

“Jake was on that team two years ago. He ran the 4x100 for us,” Rodriguez said. “We’ve kind of had our eyes on this the last two years. Last year we fell short a little bit, and this year the kids were hungry. They worked their butts off all year long, running in the summertime, running in the hallways in the wintertime, just getting ready for this moment. It’s awesome. It’s awesome to see.”

In the 400 relay, Machiniak was joined by Zander White, Samuel Magesa, and Kameron Autry. In the 800, it was Magesa, White, and Noah Jarvis.

Notre Dame Prep senior Zachary Mylenek took first place in the 400, finishing nearly a second better than his personal-record time of 48.49 seconds, and he was runner-up in the 200 (with a personal season-record 21.92).

Bound for Purdue University, where he plans to study mechanical engineering and perhaps walk on to the Boilermakers’ track team, Mylenek also anchored Notre Dame Prep’s seventh-place 1,600 relay team.

He adapted to his circumstances and performed at a high level.

He adapted to his circumstances and performed at a high level.

“The rain sucked, but I’ve been fortunate enough because we’ve been running in the rain a lot this year and I ran last year in it,” he said. “I just ran my race and other guys, I was listening, they don’t like running in the rain. It’s a mindset thing, and I just dialed in.”

Grosse Ile junior Sam Vesperman repeated in pole vault with an effort of 14 feet, 7 inches.

Vesperman was not expected to win last year, and he pulled it off. Being ranked No. 1 in pole vault coming into Saturday’s meet created more pressure for him.

“It was definitely different because I was projected to win it (this season),” Vesperman said. “Last year I was the second guy, right – I wasn’t the big name. It was definitely different having everybody (saying), ‘Oh, that’s the guy to get, so … .’”

Vesperman’s official personal record in pole vault is 15-3. On Saturday, he was pushed by Whitehall senior Ca’Mar Ready, who turned in a PR effort of 14-4, but Vesperman was able to execute when needed.

“Yeah, it’s really nice to win, but we just keep chasing that next bar, that next height. That’s definitely the motivational factor,” Vesperman said.

Other event winners included: Clio’s Elliott Sirianni in the 800 (1:55.09 PR), Freeland’s T.J. Hansen in the 1,600 (4:11.31), Pinckney’s Paul Moore in the 3,200 (9:07.53), Grand Rapids Catholic Central’s Mill Coleman in the 110 hurdles (14.49), Charlotte’s Cutler Brandt in the 300 hurdles (38.48), Coopersville’s Gabe VanSickle in the shot put (61 feet, 2 inches), Wayland’s Adam Huff in discus (172-0), and Stevensville Lakeshore’s Declin Doroh in high jump (6-7) and Kaden Griffiths in long jump (22-9.25).

Hamilton won the 1,600 relay (3:23.40), while Marshall took first place in the 3,200 relay (7:48.49). Chelsea senior Jacob Nelson won the 100, 200 and 400 adaptive events.

Rodriguez started coaching at Berrien Springs in 2012, and he became head coach in 2014.

He said the Shamrocks improve in practice because there’s a lot of competition. Everybody is chasing Machiniak.

“I mean, we have Jake Machiniak, one of the top sprinters in the state, in practice and the kids want to beat him. They don’t just want to just, like, run with him; they want to try and beat him, so that competition in practice has been huge,” Rodriguez said.

“I’m just very proud of them. We showed up on the days that were important. On a big meet like this, it’s about being your best today – we had our best on the best day.”

Like Vesperman, Machiniak entered the 2024 season with a lot of pressure. He noted, however, that the only way to improve is to put oneself in pressure situations.

Machiniak said this team title feels better than the one won in 2022 because he played a bigger role. There’s strength in numbers, though, and Berrien Springs has been known to possess depth, especially in the sprints.

“That’s all Coach Rodriguez. Best coach in Michigan – it’s not even close,” Machiniak said. “He has us training in the offseason. He has us training winter, summer, spring, fall – all the time, man. We have a lot of guys at the state meet that come (put in the work) in the offseason, all year round. Year-round athletes that do speed training. As far as the sprints, that’s all Jonny Rodriguez – best coach in the nation.

“This group, I’ve grown up with this group, man. I’ve known these guys for a while. I’ve grown with them, I’ve trained with them, I’ve cried with them. You know, these are the guys that I’ve grown up with.”

PHOTOS (Top) Berrien Springs’ Jake Machiniak, second from left, crosses the finish line first in the 100 during the Lower Peninsula Division 2 Finals on Saturday. (Middle) Pontiac Notre Dame Prep’s Zachary Mylenek, left, and Corunna’s Wyatt Bower race to the finish in a 200 prelim. (Click for more from Dave McCauley/RunMichigan.com.)