'Midnight Express' Got Start at Cass Tech

April 11, 2017

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

If Eddie Tolan had his way, he might have been a football hero or, maybe, a star on the baseball diamond. But fate is a funny thing.

Instead, he became an Olympic track star and, one can strongly argue, the Michigan High School Athletic Association’s greatest athlete of all-time.

A heart attack took him early, at the age of 57 in late January, 1967. His kidneys had failed him two years prior, and were the primary reason for his early death. Easily recognizable by his horn-rimmed glasses, Tolan would inspire generations of athletes during his lifetime and in the years that followed. Recognition for his accomplishment, via induction to Halls of Fame, would mostly arrive after he departed.

“Eddie was just Eddie,” said his youngest sister, June, “very humble and gentle. He enjoyed meeting and knowing other people, and was loved by children.”

Born Thomas Edward Tolan, Jr., in Denver in 1908, Eddie and his family moved to Salt Lake City when he was young. His father, a hotel cook, then moved his wife and their four children to Detroit when Eddie was 15. Stories of opportunity for African-Americans had prompted the move.

Within the family, Eddie’s older brother, Hart, his senior by a year, was considered the better athlete.

“Only Hart neglected to train,” said sister Martha. “Eddie was a worker.” His mother, Alice, simply described Eddie as more determined.

Following in the footsteps of his brother, Eddie joined the football team at Detroit Cass Technical High School in the fall of 1924. A sub on the squad, Eddie emerged as the team’s quarterback in the fall of 1925 under the school’s new football coach, William Van Orden. Although Eddie stood only 5-foot-4, he threw a beautiful pass. He was also lightning fast, light, and evasive. It was here, on the football field, that it seemed he would find stardom.

While the team saw limited success in the early going, Eddie quickly emerged as the star. He scored the lone touchdown in the Mechanics’ 12-6 season-opening loss to Detroit Southwestern. Held scoreless in the second game of the season, Cass Tech tied Southeastern, 6-6, in the season’s third game. The next week, the team exploded for 47 points, shutting out the Detroit Western Cowboys in “one of the biggest upsets of the current season,” according to the Detroit Free Press. Tolan accounted for four of Cass Tech’s seven touchdowns. His brother, Hart, also scored that day. Despite what the future held, it was the moment he would always rank as his favorite among his athletic achievements. Football was Eddie’s favorite sport, followed by baseball.

While the team saw limited success in the early going, Eddie quickly emerged as the star. He scored the lone touchdown in the Mechanics’ 12-6 season-opening loss to Detroit Southwestern. Held scoreless in the second game of the season, Cass Tech tied Southeastern, 6-6, in the season’s third game. The next week, the team exploded for 47 points, shutting out the Detroit Western Cowboys in “one of the biggest upsets of the current season,” according to the Detroit Free Press. Tolan accounted for four of Cass Tech’s seven touchdowns. His brother, Hart, also scored that day. Despite what the future held, it was the moment he would always rank as his favorite among his athletic achievements. Football was Eddie’s favorite sport, followed by baseball.

With the goal of avoiding injury and damage to Detroit’s prep gridirons, a heavy five-hour downpour on Saturday, Oct. 24 meant Cass Tech’s game with Hamtramck was rescheduled for Monday the 26th at Northwestern High School.

Despite the delay, the teams squared off on a field that was in worse condition than it had been Saturday. Early in the first quarter, the heavier Hamtramck squad dashed Cass Tech’s hopes for a shot at contending for the Detroit Public School League crown. Thrown for a four-yard loss, Eddie Tolan “was left lying in the mud, the victim of several torn ligaments.”

Cass Tech lost the game, 12-0, and Eddie Tolan was lost for the season.

“Rated as one of the best forward passers in the city, Tolan combined all the qualities of a first class quarterback,” noted the Free Press a few days later, “and his loss is a death blow to the chances of Cass finishing near the top.”

In spite of the injury, Eddie had been impressive enough to be named quarterback on the paper’s All City third-team squad at season’s end.

He would never return to the gridiron.

Birth of a legend

Back in the 1920s, winter meant indoor track for preps. It was the age of dynasties, where the sport at a team level was ruled by the public schools of Detroit, and one school in particular – Detroit Northwestern. The Colts had won four of the last five indoor city meets as the public schools entered the 1925 track season, and they would again reign that spring.

As it remains today, skill was needed across both track and field events to dominate as a team. Still, there was room for individuals to shine. Tolan arrived on the track scene during this time, and as a sophomore, showed early promise.

It was the golden age of athletics, as well as newsprint. Today it’s hard to imagine a time when track headlines could snake their way to the top of the sports page of a big city newspaper, highlighting the accomplishments of the local preps. Yet in the 1920s and 1930s, that was the case. Tolan earned two spots in the annual city meet in 1925, appearing in the 30 and 220-yard dashes. While he failed to place among the leaders in the furlong, Eddie did finish fourth in the 30-yard dash, behind three runners from Northwestern, including Charles “Snitz” Ross, the winner of the event and the city’s emerging sprint star. Unfortunately, Tolan’s finish was disqualified, as he had run out of his lane.

On March 20 and 21, the first indoor interscholastic track and field meet was hosted at the University of Michigan. The two-day event featured 20 in-state schools, and a pair from outstate – Waite High of Toledo and Austin High of Chicago. A total of 185 athletes showcased the university’s newly opened Yost Fieldhouse while competing in 12 events. The competition was ruled by Detroit Northwestern, with first-place finishes in eight of the events and a total of 51½ points. Cass Tech finished a distant second with 14 points. Tolan earned a second place in the 50-yard dash, behind Ross of Northwestern, the winner of the race.

On March 20 and 21, the first indoor interscholastic track and field meet was hosted at the University of Michigan. The two-day event featured 20 in-state schools, and a pair from outstate – Waite High of Toledo and Austin High of Chicago. A total of 185 athletes showcased the university’s newly opened Yost Fieldhouse while competing in 12 events. The competition was ruled by Detroit Northwestern, with first-place finishes in eight of the events and a total of 51½ points. Cass Tech finished a distant second with 14 points. Tolan earned a second place in the 50-yard dash, behind Ross of Northwestern, the winner of the race.

Eddie’s skills continued to bloom during the outdoor season, which began in April. There, the sophomore excelled in the 100 and 220 events. A breakout performance at a late-season triangular meet with Northwestern and Southwestern, where Eddie defeated Ross in the 100-yard, caught the attention of many. His time of 10.2 seconds tied the city record, established by George “Buck” Hester of Detroit Northern in 1922. Born in Windsor, Ontario, Hester had competed for Canada in the 1924 Olympics, hosted in Paris. He would run collegiately at the University of Michigan.

At the same meet, Tolan topped the city mark in the 220-yard dash, covering the distance in 23.1 seconds.

Less than a week later, Ross toppled the century mark, with a 10.1 in the preliminaries to the city’s outdoor meet. A rivalry, bubbling at the surface, now exploded.

Anticipation for the showdown between Ross and Tolan at the city finals in the 100 was met with disappointment among fans, as Tolan won the race with a spurt in the final three steps to the wire, posting a 10.4 time, while Ross finished fourth. Tolan also won the 220 while Ross did not place. John Lewis of Northeastern finished second in both events.

Junior William Loving of Cass Tech emerged as the city’s outstanding performer, “taking first place in the high jump, and both hurdles, aside from running in the relay and finishing third in the discus,” that Saturday, May 16 at Codd Field. The performances still were not enough to unseat Northwestern, the winner of the meet.

Junior William Loving of Cass Tech emerged as the city’s outstanding performer, “taking first place in the high jump, and both hurdles, aside from running in the relay and finishing third in the discus,” that Saturday, May 16 at Codd Field. The performances still were not enough to unseat Northwestern, the winner of the meet.

Northwestern also won the 25th Annual Outdoor meet at the University of Michigan. Loving finished as the high point winner at the event, while Tolan tied with Lewis of Northeastern for second in the century dash, behind Jimmy Tait of Northwestern. Ross finished fourth.

Beginning with their victory in 1920, Northwestern also ruled the annual state track championship in East Lansing, clinching the Class A title in four of the previous five years under the guidance of Bert Maris. (The 1922 Class A title was won by Detroit Northern).

At the first championship sponsored by the newly formed Michigan High School Athletic Association, the result was the same. This time, Maris was assisted by Warren Hoyt, and it took a prep “world’s record in the 880 relay” to top Cass Tech. Northwestern ended the day with only three first-place finishes. Team depth had allowed Colts to win the meet with 38 points against 34 2/3by the Mechanics.

Cass Tech’s Loving ended the day with the top point total for an individual, with 12½, while his teammate Tolan added 10 points, by winning both the 100 (10.1) and 220-yard (22.4) dashes. While expected to do well, the sophomore was still an underdog in each event. Lewis again finished second in both events, while Tait landed third place and Ross finished fourth in the 100.

The injury, and a reminder

Following the football injury, Tolan was still unable to perform in January when the 1926 indoor track season opened. However, the high school junior was back in February in time for the Mechanics’ dual meet with Northwestern. Sporting a bandage on his left knee, Tolan topped Ross in the 30-yard dash. The bandage, covering the knee, would remain with him for the rest of his running career, symbolic of that return victory.

Hopes ran high that Cass Tech might challenge the Colts for the city’s indoor title in 1926, but it didn’t turn out that way. Northwestern again dominated the city’s seventh annual meet, winning five of the day’s first nine events. Ross and Tolan tied at the tape in the 30-yard dash, but the run was tainted. Ross’ “eagerness to outsprint Tolan, his most bitter rival,” resulted in two false starts, and Ross was set back two feet to begin the race. Without the penalty, there was little doubt that Ross would have won the event cleanly.

At the Second Annual Indoor Interscholastic, held at Yost Fieldhouse on March 20, George Simpson of East Columbus, Ohio, grabbed the 50-yard dash crown. Ross earned second in the race, while Tolan finished fourth. Detroit Northwestern again won the invitational, but this time in less-dominating fashion, as the field of participating schools was greatly expanded.

Multiple Detroit athletes were selected to compete at the prestigious Northwestern University Indoor prep invitational, scheduled for the following week in Evanston, Ill. Loving finished as high point scorer of the meet with 11, with a win in the 60-yard high hurdles and second-place finishes in the low hurdles and high jump. Combined with Tolan’s second-place finish in the 50-yard dash, the pair totaled 14 points, enough to win the event. Cass Tech’s return to Detroit as champion was loudly trumpeted in the press.

Based on the performance at the national level, the Mechanics were identified as strong candidates to dethrone the Colts during the upcoming outdoor season. Despite strong results at duals and triangular meets, Cass Tech still fell to Northwestern in total points at the annual city carnival.

Finally, a team victory

At the 26th annual University of Michigan outdoor interscholastic meet, Cass Tech scored its biggest triumph, surprising “the best of the schoolboy athletes from Detroit, Toledo and Chicago, without mentioning stars from the states of Michigan, Ohio, Illinois and West Virginia at large.” Amazingly, Kalamazoo Central also slipped past Detroit Northwestern in the standings. The Colts had to settle for a third-place finish at Ann Arbor.

While rain and cold temperatures meant record performances were few, Tolan won the 100, over Jimmy Patterson of Chicago Tilden Tech (winner of the 50-yard indoor race at Northwestern University earlier in the spring), Lewis of Northeastern and Ross of Northwestern, with a time of 10.3. His 22.1 seconds in the furlong topped Patterson, Edgar Fenker of Kalamazoo Central and Lewis, respectively.

Of course the Colts were expected to find redemption at the 20th annual state track and field meet, scheduled for May 28 and 29 at Michigan State College. As expected, both Northwestern and Cass Tech, along with Kalamazoo Central did well at the preliminaries. Yet, in a stunning turn of events, the finals mimicked that of a week before with Cass Tech, guided by Coach Van Orden, winning the Class A state title, followed by Kalamazoo Central, then Northwestern. Loving and Tolan were the stars of the event. Tolan “romped” in the 100 and 220 dashes, while Loving, now a senior destined for Western State Teachers College, repeated as winner of both the high and low hurdles.

Graduation gutted Cass Tech’s track roster, and by the time of the indoor city meet in 1927, only Tolan remained to take on Northwestern’s juggernaut. Jack Dant of Northwestern surprised everyone with a new city record in the furlong, with a 24.7 in the preliminary of the city meet. The mark would stand as the city indoor record for 24 years until topped in 1942. In the finals, Tolan grabbed top honors in the 30-yard dash and finished second in the 220. Dant placed fourth, with each runner trailing Edward Swan, captain of Northwestern. The Colts again reigned as city champions. Two weeks later on the 19th, Tolan won the 50-yard dash at the Third Annual Indoor event at the University of Michigan. At Northwestern University’s national indoor championships on March 26, he won the 50, running the distance in 5.3 seconds.

Tolan’s star shined brightest during the outdoor season. On May 14th at the University of Michigan’s annual outdoor interscholastic, Tolan won the 100 and 220 dashes. On the 22nd, he captured the same two events at the city’s outdoor meet.

Tolan’s star shined brightest during the outdoor season. On May 14th at the University of Michigan’s annual outdoor interscholastic, Tolan won the 100 and 220 dashes. On the 22nd, he captured the same two events at the city’s outdoor meet.

One week later, for the first time in history, all four classes of Michigan high schools met for the state championships in East Lansing. Favored to win, Tolan closed out his career by matching Hester’s record time of 9.8 seconds in the 100 – a mark thought unattainable. With little rest, he then fought off Kalamazoo’s Fenker in the 220, winning by a stride with a time of 21.9. The victories meant Tolan was undefeated in each event over his three years running at the MHSAA state championships.

Northwestern returned as team champion, this time coached by Malcolm Weaver. Outside of back-to-back team victories in 1916 and 1917 by Grand Rapids Central, the Class A crown had been possessed by Detroit schools in 11 of the past 14 years. (No meet was run in 1918 due to World War I.)

Tolan wrapped up his high school career at the University of Chicago. One of 14 Detroit area athletes invited to the Interscholastic Track Championships, Tolan equaled the prep world’s record time of 9.8 seconds in the 100-yard dash, then grabbed the furlong, topping runners from Minnesota, Iowa, Illinois and Indiana.

Accurate or not, news spread from coast-to-coast via the media wire of Tolan’s track skill, noting he had won 17 out of 18 city and state outdoor championships in three years of prep competition.

As a junior, Tolan had run Amateur Athletic Union track, sponsored by the Detroit Department of Recreation in the summer, and he returned to AAU competition following graduation, running against active and former college track luminaries. At the state track championships at Belle Isle on July 4, Tolan starred. Running for the Detroit Athletic Association team, he won the 100 and 220, topping Victor Leschinsky, former University of Michigan sprinter.

Next stop: Ann Arbor

While enrolled at U-M, in January of 1928, Tolan was named a 1927 High School All-American by the AAU. At Michigan, he earned the nickname “Midnight Express” and began to chew gum while racing.

As a sophomore, Tolan tied the world’s record in the 100-yard dash, laying down a 9.6-second time at the Western Conference preliminaries at Evanston, Ill, against George Simpson, a former prep opponent from Columbus, Ohio, now running for Ohio State. One day later, on May 25, 1929, at Duche Stadium at Northwestern University, Tolan bested the mark.

With a slight breeze at the runners’ backs, Tolan came from behind, and “with his big horn-rimmed spectacles firmly taped to his head, electrified the crowd by winning the 100-yard dash in :09.5 seconds. He beat Simpson to the tape in an eyelash finish that was inconceivably close.”

These were the days when starting blocks were still not accepted for official races. It took a year before the International Amateur Athletic Association pronounced the mark as the new world’s record.

By college graduation, Eddie had run the 100 a total of 143 times for the Wolverines, losing the race on only nine occasions.

An Olympic hero

While the participants and witnesses have been silenced by father time, their voices gone thanks to the ailments that arrive as we age, Tolan’s exploits at the 1932 Olympics have been well recorded.

After graduation, Tolan and the nation’s top sprinters traveled North America, racing in preparation for the Olympic trials. When they finally arrived, he was beaten by Ralph Metcalfe of Marquette University in both the 100 and 200-meter races. Still, the top three times qualified, and both men, along with old rival George Simpson, made the Olympic roster.

It was a time where the press was very cognizant of skin color and quick to note that this was the first time that the top two individual sprinters representing the United States were African-American. At the games, staged in Los Angeles, Tolan became the first African-American to receive the title “world’s fastest human” when he edged Metcalfe in the first-ever photo finish in the 100-meter race, and then earned a second gold with victory in the 200-meter event. His time in the 100 would remain an Olympic record until 1960.

It was a time where the press was very cognizant of skin color and quick to note that this was the first time that the top two individual sprinters representing the United States were African-American. At the games, staged in Los Angeles, Tolan became the first African-American to receive the title “world’s fastest human” when he edged Metcalfe in the first-ever photo finish in the 100-meter race, and then earned a second gold with victory in the 200-meter event. His time in the 100 would remain an Olympic record until 1960.

Tolan returned to Detroit to a hero’s welcome when his train arrived at Michigan Central Station in late August. The acclaim continued at city hall, then at the Brewster Recreation Center, where he celebrated with friends and family. September 6, 1932, was declared “Eddie Tolan Day” by Michigan governor Wilber Brucker.

This country was in the depths of the Great Depression, and opportunity for all Americans was limited. But while his had become plentiful, Tolan had no plans to “cash in” on his fame, and he expected to remain an amateur.

For a short time following the games, he joined Bill “Bojangles” Robinson on the vaudeville circuit. There, he described his Olympic success to attentive crowds. It was ruled that the venture violated his amateur status. In 1933, with both his father and brother out of work, Tolan found employment as a filing clerk in the register of deeds office of Wayne County. In 1934, he was offered a chance to race professionally in Australia. Following a six month barnstorming tour, he returned home, resuming his position with Wayne County.

In 1937, he was appointed to Michigan’s National Youth Administration, where he assisted other African-Americans with vocational guidance and placement. He continued to support his parents financially. In his final years he worked as a physical education teacher in Detroit.

A bachelor all his life, in 1954 Tolan lost his mother to old age. Later in the year, he was named to a roster of 22 all-time greatest U.S. Olympians. In 1958, he was inducted into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame along with five others. Only 12 names had preceded the group, and Tolan was just the second African-American honored by the Hall.

“Oh, man, it was a terrible thing,” said Jessie Owens, four-time U.S. gold medalist at the 1936 Olympics, discussing the loss with Jet magazine at the time of Tolan’s death in January 1967. “When I was in high school, Eddie and Ralph (Metcalfe) were my idols. Eddie and I later became close friends. I used to live in Detroit, and every time I’d go back Eddie was one of the first ones I’d look up.”

Posthumously, in May 1967, a 17-acre playground on Detroit’s east side, near the Children’s Hospital of Michigan, was dedicated with his name. An artificial kidney machine, purchased for Wayne County General Hospital with funds raised by his sisters, was donated in his honor in 1969.

Eddie was inducted into the University of Michigan’s Athletic Hall of Honor along with 10 others at the university’s third induction in 1980 and was added to the National Track and Field Hall of Fame along with its ninth class in 1982. Today, medals and a pair of his track shoes, donated by his sister, June Tolan Brown, are on display at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

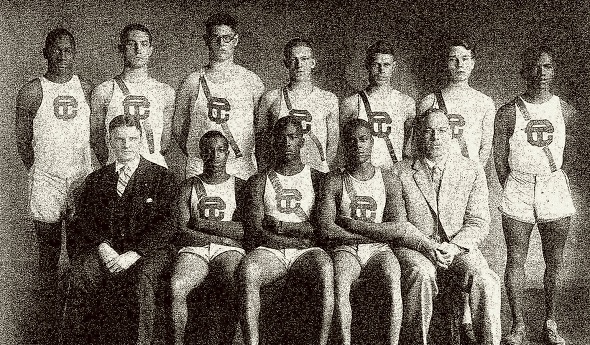

PHOTOS: (Top) The 1926 Detroit Cass Tech track & field team was led by a handful of standouts including the emerging Eddie Tolan. (Middle top) Tolan, in 1925. (Middle) Detroit Northwestern standout Charles Ross. (Middle) Bill Loving, also a Cass Tech star. (Middle below) The program cover from the 1927 MHSAA Track & Field Finals. (Below) Tolan after the World Professional Sprint Championships in Melbourne, Australia, in 1935. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch with assistance from Detroit Cass Tech's Regenia Kirk.)

'Over Here,' Athletes Gave to WWI Effort

March 28, 2018

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

In a nation at war, the needs of many outweigh the desires of a few.

Among the many noble sacrifices for the greater good was Michigan’s spring high school sports season of 1918.

The United States’ entry into “The Great War” (today commonly known as World War I) came on April 6, 1917, 2½ years after the war had begun. First elected President of the United States in 1912, Woodrow Wilson earned re-election in 1916 under a platform to keep the U.S. out of the war in Europe. The sinking of the British passenger ships Arabic and Lusitania in 1915 caused the death of 131 America citizens, but did not invoke entry into the conflict. However, continued aggressive German actions forced a reversal in policy.

“The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind,” stated Wilson in an April 2 special session of Congress, in requesting action to enter the war.

A huge baseball fan, President Wilson recognized the value of entertainment and athletics during a time of crisis. Major league baseball, America’s pastime, completed a full schedule in 1917. A former president at Princeton University, on May 21, 1917, Wilson addressed the value of school athletics in a letter to the New York Evening Post.

“I would be sincerely sorry to see the men and boys in our colleges and schools give up their athletic sports and I hope most sincerely that the normal courses of college sports will be continued so far as possible, not only to afford a diversion to the American people in the days to come when we shall no doubt have our share of mental depression, but as a real contribution to the national defense. Our young men must be made physically fit in order that later they may take the place of those who are now of military age and exhibit the vigor and alertness which we are proud to believe to be characteristic of our young men.”

“I would be sincerely sorry to see the men and boys in our colleges and schools give up their athletic sports and I hope most sincerely that the normal courses of college sports will be continued so far as possible, not only to afford a diversion to the American people in the days to come when we shall no doubt have our share of mental depression, but as a real contribution to the national defense. Our young men must be made physically fit in order that later they may take the place of those who are now of military age and exhibit the vigor and alertness which we are proud to believe to be characteristic of our young men.”

Despite the highest of hopes, the requirements and realities of war deeply impacted life in the U.S. soon after.

In February of 1918, a proposal was circulated by Dr. John Remsen Bishop, principal of Detroit Eastern High School and president of the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association, to abolish spring athletics at Michigan high schools. Due to a labor shortage brought on by the war, the states, including Michigan, needed help on farms, harvesting crops from spring until late fall. The action might also affect the football season of 1918.

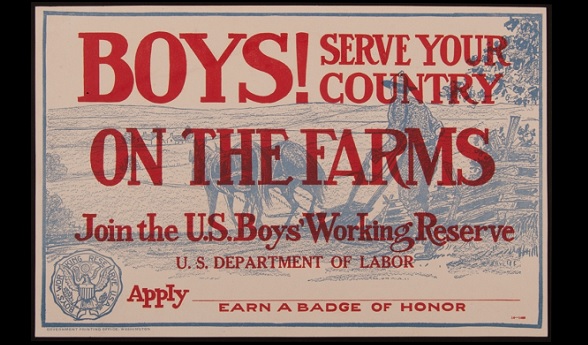

The Boys’ Working Reserve, a branch of the U.S. Department of Labor, was organized in the spring of 1917 and designed to tap into an underutilized resource to help address that labor deficiency. “Its object was the organization of the boy-power of the nation for work on the farms during the school vacation months.”

While the idea was popular among schools around Detroit, due to the lack of public commentary from outstate school administration, it was expected that the proposal would meet at least some opposition when the M.I.A.A. gathered on Thursday, March 28 in Ann Arbor during a meeting of the state’s Schoolmasters Club.

Less than two weeks prior to the March meeting, Michigan Agricultural College made an announcement that would impact one aspect of the coming spring sports season.

“The department of athletics of the Michigan Agricultural College begs to inform the high schools of the state that plans for the annual interscholastic track meet, which was to have been conducted here in June, have been given up this year – not through any desire on the part of this department to discourage athletics, but because this is a time when we can and should devote our resources to better uses,” said coach Chester L. Brewer of the Aggies to the Lansing State Journal. “It would hardly be sound judgment for us to make our usual elaborate plans for this meet while our government is appealing to all of us to economize and exercise the utmost thrift. Neither is it wise policy to encourage unnecessary traveling upon the railroads, or to ask high schools of the state to make any expenditures other than those which are absolutely necessary.”

Earlier in the year, similar news had come from the University of Michigan.

In January of 1917, the University of Michigan had announced plans for an elaborate annual high school basketball invitational, designed to identify a Class A state champion. Billed as the “First Annual Interscholastic Basket Ball Tournament,” the March event hosted 38 teams. However, influenced by the war, a decision had been made not to run a second tournament in 1918. Instead, on March 27, Kalamazoo Central and Detroit Central, two of the state’s top teams, were invited to Ann Arbor for a hastily arranged contest at U-M’s Waterman Gymnasium. The schools had split a two-game series during the regular season. Kalamazoo won the season’s third matchup, and while not official, declared itself 1918 Michigan state champion.

Into this environment of patriotism and uncertainty, school administrators arrived in Ann Arbor for the Schoolmasters gathering. There, in the morning, the membership heard a presentation from H. W. Wells, assistant and first director of the Boys’ Working Reserve. “The heart of the nation, rather than the hearts of the nation, is beginning to beat. War is making us a unit,” said Wells, discussing the aim to recruit boys between the ages of 16 and 21 to help provide food for the allies in Europe and at home in the United States.

“Wells told of the need for the farmers to sow more wheat, and plant more corn,” reported the Ann Arbor News, “and in the same breath he told of great corn fields all over the country, where last year’s corn still lay unhusked, because of a lack of farm labor.”

“Wells told of the need for the farmers to sow more wheat, and plant more corn,” reported the Ann Arbor News, “and in the same breath he told of great corn fields all over the country, where last year’s corn still lay unhusked, because of a lack of farm labor.”

It was estimated that 25 percent of the nation’s farm workforce was now active in the armed forces.

The proposition was brought to the M.I.A.A. by Lewis L. Forsythe, principal at Ann Arbor High School, who would soon establish himself as a guiding force in high school athletics. The proposal “was discussed thoroughly.”

“This session is usually a stormy one, because of contentions that arise over rulings that affect schools in different ways,” said Adrian superintendent Carl H. Griffey to the Adrian Daily Telegram, “but this meeting was a serious one in which all matters were related to our national welfare and passed by unanimous votes.”

So, one day after the conclusion of the abbreviated state basketball championship contest, the spring prep sports season in Michigan came to an abrupt halt. Michigan’s male high school students were asked to work to support the war effort.

“Chances are that they will remain there for the duration of the war,” stated the Lansing State Journal in response to the action. “At the meeting … it was talked of quitting football because of the need of the boys staying on the farms till the latter part of November. This is highly probable. If it is passed upon then Michigan high schools will have but one sport, basketball.

“Whether intra-mural sports will replace the representative teams is not known. This form of athletics demands the attention of a great number of teachers to tutor the different class organizations. The teachers are taxed to the limit at present and cannot give the time to sports. Organizing farm classes and Liberty bond teams is taking the teacher’s spare moments. … But still athletics are needed, as the war has demonstrated, and physical training should be instituted from the kindergarten to the university.“

“Those lads who leave for the farms the first of May,” wrote the Port Huron Times-Herald, “will be in better condition when they return home from the fields and cow lanes than they would (have) had they remained in the city until June batting the leather pill.”

The fate of the 1918 football season would not be known until late August.

In late June, the 29th Governor of Michigan, Albert E. Sleeper, thanked the estimated 8,000 students who had joined the ranks.

“To you soldiers of the soil I would say this, that I am as proud to address you as I would be to address any of the boys who are bearing arms for their country. You have proved that you are true patriots, for you have started out to do exactly what your country has asked you to do – the thing which you can do best for your country at this time.

“To you soldiers of the soil I would say this, that I am as proud to address you as I would be to address any of the boys who are bearing arms for their country. You have proved that you are true patriots, for you have started out to do exactly what your country has asked you to do – the thing which you can do best for your country at this time.

“Every day, in the rush of official work, I think of you Reservists as you work on the farms, just as I think of our soldiers who are in training camps or ‘over there.’ And I am just as proud of you as I am of them. So are all the people of Michigan.”

It was estimated “the boys who last spring left their high school studies and as members of the United States Boys’ Reserve have helped the Michigan division to add $7,000,000 to the food production of the nation.”

In September, Byron J. Rivett, secretary of the M.I.A.A., announced that, based on a vote of member high schools, prep sports would be resumed in the fall. The Detroit News celebrated the news that “moleskins and pigskins will be in evidence and the grand old game will be a part of the autumn’s entertainment.”

In October, in Grand Rapids and Detroit and other cities across the state, officials gathered to honor those who served as part of the “Michigan Division of the Reserve” and to award bronze badges in recognition for their contribution to the war effort.

World War I officially ended on November 11 with the signing of the armistice. Armistice Day, today known as Veteran’s Day, was first celebrated in 1919. In total, an estimated 16 million were killed during the war.

“Four million ‘Doughboys’ had served in the United States Army with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Half of those participated overseas,” said Mitchell Yockelson in Prologue magazine, a publication of the National Archive. “Although the United States participated in the conflict for less than two years, it was a costly event. More than 100,000 Americans lost their lives during this period.”

More than 5,000 of those casualties had come from Michigan.

***

To the surprise of the world, a second war arrived in 1918. This one did not discriminate based on geographic or political borders. It would take more lives than World War I.

To the surprise of the world, a second war arrived in 1918. This one did not discriminate based on geographic or political borders. It would take more lives than World War I.

Globally, the Spanish Flu pandemic arrived in three waves, one in the spring, one in the fall of 1918, and a third arriving in the winter of 1919 and ending in the spring. It, too, would impact high school and college athletics in Michigan and beyond, as countless football games across the nation were cancelled in an attempt to help reduce the spread of the disease.

In the end, an estimated 675,000 would die in the United States from the virus. In Michigan, hundreds succumbed in October 1918 alone. In Detroit, between the beginning of October and the end of November, “there were 18,066 cases of influenza reported to Detroit’s Department of Health. Of these, 1,688 died from influenza or its complications.” Worldwide, an estimated 50 million were killed by the Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) The U.S. Department of Labor recruited high school students to work on farms as soldiers went oversees to fight World War I. (Middle top) A Working Reserve badge. (Middle) Lewis L. Forsythe. (Below) Another recruitment poster for the Working Reserve shows a man plowing a field while war rages in the background. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)