The Last Time MHSAA Finals were Canceled

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

April 27, 2020

Historians trace the start of World War II to German dictator Adolph Hitler’s decision to invade Poland on September 1, 1939. The Empire of Japan’s involvement in the war became effective in September 1940 with the signing of the Tripartite Pact.

Until December 7, 1941, the United States avoided official involvement, declaring themselves “a neutral nation.” Then came Imperial Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor.

A labor shortage caused by World War I had taken out spring high school sports in Michigan in 1917. As noted in the Second Half article, “1918 Pandemic, WWI Threatened High School Sports,” the global spread of a devastating strain of influenza interrupted the football season in Michigan. Prep athletics would roar through the 1920s and survive the Great Depression before seeing another interruption.

That next disturbance had nothing to do with war’s insatiable desire for manpower. Rather, it was because of tires.

“When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, rubber instantly became the most critical strategic material for making war,” wrote Stephen W. Sears in the October/November issue of American Heritage magazine in 1979. “Nine-tenths of the nation’s rubber came from the Far East, and it was painfully evident that nothing would now stop Japan from cutting off that source.”

Americans consumed nearly two-thirds of the world’s production of rubber. With only about a year’s worth of material on hand, “Just four days after Pearl Harbor a freeze was put on the sale of new passenger-car tires,” stated Sears, “and on December 27 tire rationing was authorized, to go into effect early in January, 1942. Sales of new cars also were halted.”

The MHSAA

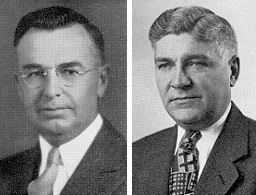

The Michigan High School Athletic Association arrived in December 1924. It replaced the old Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association which had served Michigan for 15 years.

The organization’s primary purpose was to standardize, interpret and administer rules, educate and guide officials, and regulate student eligibility within prep sports in Michigan. By the 1940s, it had evolved into an association that also managed postseason tournaments, designed to identify state champions in specific sports: swimming, cross country, golf, tennis, track, and the sport sponsored by the most high schools in the state, basketball.

“The old MIAA had taken over the regulation of basketball tournaments in 1920. This had been done as a service to the schools and especially as a means of eliminating evils inherent in the invitational tournaments (that were hosted by various colleges around the state and the midwest),” wrote Lewis L. Forsythe in his book, Athletics in Michigan High Schools, recalling the first 100 years of prep sports in the state.

“The old MIAA had taken over the regulation of basketball tournaments in 1920. This had been done as a service to the schools and especially as a means of eliminating evils inherent in the invitational tournaments (that were hosted by various colleges around the state and the midwest),” wrote Lewis L. Forsythe in his book, Athletics in Michigan High Schools, recalling the first 100 years of prep sports in the state.

“In the last days of February 1942,” multiple Michigan schoolmen were in San Francisco to attend the annual meetings of Secondary School Principals, Superintendents and the National Federation of State High School Associations. “We were well aware that many of our boys in school would have to offer themselves in the service of their country,” noted Forsythe in his publication. “We fully realized that the quality of that service and, indeed, their own survival might well depend quite as much on their physical fitness as on their intellectual and spiritual resources. It was under those circumstances that we determined so to modify the emphasis of our athletic program as to make the largest possible contribution to the war effort. We recognized that the need in Michigan could not be met by our organization alone, and we therefore determined to encourage a general enrollment of all school groups in a united effort for promotion of physical fitness.”

Because of the “scarcity of tires and automobiles,” in April 1942 the MHSAA announced plans to curtail their upcoming annual golf and tennis events, eliminating a state championship round. Instead, the seasons were concluded with separate eastern and western sectional tournaments, hosted in Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids.

Early in May of 1942, MHSAA executive director Charlie Forsythe, nephew of Louis Forsythe, announced that the Association was “working on plans designed to make body-building exercises available to more young men and to spread recognition of sports achievements. He predicted substantial growth of intramural sports to include youngsters whose limited prowess might keep them from such interscholastic sports as football, baseball or basketball.”

Wire articles had told the story of how the running Battle of the Atlantic had impacted U.S. ocean transportation along the eastern seaboard. A Germany-mounted “campaign against American coastal shipping” by U-boats (submarines) was devastating “a section of America almost exclusively dependent upon ocean-point tankers for its petroleum products.” Without a viable alternative means to transport the products, on May 15, 1942, gasoline rationing began in 17 seaside states and the District of Columbia. It was hinted that gas rationing – specifically designed to save rubber – could roll out nationally. (Crude oil is the main ingredient in man-made rubber.)

The chances for restrictions in Michigan were a distinct possibility. According to P.J. Hoffmaster, the state’s supervisor of wells, the state consumed approximately 140,000 barrels of oil per day, but produced only 64,054 barrels. “This state has a shortage of at least 100,000 barrels on the basis of a regional demand,” he said, noting Michigan oil also supported needs outside the state. “When people say there can’t be rationing in Michigan because we have plenty of our own oil, they don’t have the true picture.”

Reverberations begin

When quizzed on the subject before the annual Lower Peninsula Track and Field championships, hosted at Michigan State College in May 1942, (Charlie) Forsythe, told The Associated Press he was unsure how rationing might affect the Association’s annual playoffs.

“It is too early as yet to say exactly. … We are making every effort to maintain an adequate athletic program. Certainly where common carriers (busses and trains) will make it possible to get a team to a game, that means should be used,” Forsythe said. He added that the Association was “surprised to find the number of schools competing in this year’s tournaments practically equaled last year’s entries.”

“It is too early as yet to say exactly. … We are making every effort to maintain an adequate athletic program. Certainly where common carriers (busses and trains) will make it possible to get a team to a game, that means should be used,” Forsythe said. He added that the Association was “surprised to find the number of schools competing in this year’s tournaments practically equaled last year’s entries.”

A total of 162 schools had qualified individual contestants in the track championships, about 10 percent fewer than in 1941. However, L.L. Frimodig – the assistant director of college athletics at M.S.C. and acting director of the state track meet – felt “the actual field in the four-class carnival would be much smaller than the number eligible to compete,” considering the circumstances of travel. “Many coaches,” he said, “would think in terms of tires rather than trophies before embarking on any sizable journey to the meet.”

The threat of rationing was almost immediately seen within Michigan’s resorts and travel industry.

“July and August have been moved up into June,” wrote the Detroit Free Press. “This is the word that comes from various parts of the state. Evidently, determination to get the vacation over before gas rationing may be decreed is one of the factors that has stepped up the season. … Reports of heavy patronage at nearby resorts over Memorial Day week-end can be taken as an indication of the trend, or necessity in 1942 of holidays enjoyed close to home base.”

Come September, Joseph B. Eastman, national director of the office of war transportation, called for help in reducing consumption of natural resources: “We intend to solicit the help of colleges and universities in making arrangements for transfer of scheduled games to centers of population where as many people as possible will have an opportunity to attend football games without traveling.”

At the college level, the freshman eligibility rule was waived due to the loss of manpower tied to military enlistment and the enactment of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. Its passage required all men between ages 21 and 45 to register for the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. With entry into the war, in December 1941, it was amended to require all 18 to 64-year-olds to register, with starting age for likely draft lowered to 20.

“The seasons of 1942-45 turned the (college) game upside down, creating new juggernauts and decimating some old ones,” wrote Sports Illustrated in its 1971 article, “When Football Went to War.”

“Michigan’s 85 high school athletic leagues are speculating on the effects of the office of defense transportation plan to whittle sports travel drastically,” stated an Associated Press (AP) article soon after Eastman’s announcement. The Southwestern Conference, comprised of Kalamazoo Central, Benton Harbor, Muskegon, Holland, Grand Haven and Muskegon Heights and one of the most widely spread major prep circuits in the state, was told by its regular bus company that its busses were not available for charter.

“Michigan’s 85 high school athletic leagues are speculating on the effects of the office of defense transportation plan to whittle sports travel drastically,” stated an Associated Press (AP) article soon after Eastman’s announcement. The Southwestern Conference, comprised of Kalamazoo Central, Benton Harbor, Muskegon, Holland, Grand Haven and Muskegon Heights and one of the most widely spread major prep circuits in the state, was told by its regular bus company that its busses were not available for charter.

On Sept. 25, according to AP, “the state department of public instruction warned today that a threat of ‘no new tires’ will be held over rural schools which use their school busses to transport football players to and from games.”

Julian W. Smith, named the interim director of the MHSAA when Charlie Forsythe went into military service, didn’t think the directive would have much impact on football schedules. “However, I believe the order will have a serious effect on basketball schedules this winter and on next year’s football schedule.”

“Four Gallons a Week for Most Drivers”

Two days later it was announced that nationwide gas rationing would go into effect at the beginning of December 1942. More immediately, compulsory tire inspections every 60 days and a “Victory Speed Limit” of 35 miles per hour, effective Oct. 1, were also enacted. “This is not a gasoline rationing program, but a rubber conservation program,” said William M. Jeffers, president of the Union Pacific Railroad, which had been placed in charge of the government’s struggle to alleviate the rubber shortage.

“The object is not to take cars off the road, but to keep them on the road. … The safe life of a tire at 50 miles per hour is only half as great as it is at 30 m.p.h.”

After initial announcements of game cancellations, the impact on high school football in Michigan in 1942 appears to have been minimal. Solutions were found to most challenges. In Bessemer, the high school superintendent announced that “enough persons have volunteered their automobiles to take the Speed Boy players to Calumet” for the game, scheduled for Saturday, Oct. 3. At season’s end, Flint Northern, Detroit Catholic Central, Muskegon, and Wyandotte each lay claim to a share of Michigan’s mythical football title.

After initial announcements of game cancellations, the impact on high school football in Michigan in 1942 appears to have been minimal. Solutions were found to most challenges. In Bessemer, the high school superintendent announced that “enough persons have volunteered their automobiles to take the Speed Boy players to Calumet” for the game, scheduled for Saturday, Oct. 3. At season’s end, Flint Northern, Detroit Catholic Central, Muskegon, and Wyandotte each lay claim to a share of Michigan’s mythical football title.

But a hint of what was to follow came with an announcement concerning the annual Cross Country Finals. The state meet was cancelled to reduce travel, with honors instead awarded during October meets to which schools were assigned based on geography.

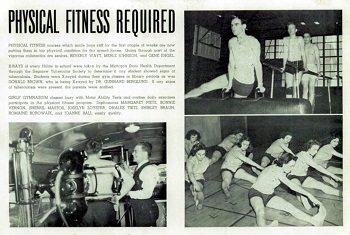

In its October 1942 bulletin, the MHSAA endorsed a commando-type “training plan drafted by the Minnesota branch of the office of civilian defense” to “step up scholastic physical fitness programs.” When plotted on a football field, the course bordered the playing area with 11 obstacles spaced 20 yards apart. The course required participants to jump a 4-foot fence, crawl under a 2-foot-high rope, then run between a maze of stakes and, later in the course, high-step through a series of open boxes. Students would scale a 7½-foot wall, walk on a 12-foot balance beam, swing across a broad jump pit from a rope that hung from above, then climb another rope hung from the crossbar of the goal posts. Once accomplished, the participant was to move, hand-over-hand, across the span of the crossbar before dropping to the ground.

At the end of October, the MHSAA’s Representative Council acknowledged the direct contribution that interscholastic sports had on the “lives of students and citizens of the communities in which they are offered” while recommending that they be “retained insofar as possible.”

The committee, however, also emphasized its belief “that physical fitness programs for all students, and intramural sports to offer opportunity for competition to all, should be stressed in the schools’ athletics program.

“In all probability,” it continued, “it will be necessary to modify the general plans of conducting tournaments.” The mechanics of modification would be hammered out at the next Council meeting to be held in December in Lansing.

Financial concerns also were expressed, as much of the Association’s operating budget came from a share of gate receipts of tournaments.

The Impact

“All over the state, athletic directors and coaches are tackling transportation problems. Instead of piling the athletes into privately owned automobiles or school busses, coaches have diligently studied timetables of regular train and bus lines with many satisfactory results,” stated the AP on Dec. 4.

That same day, the MHSAA announced that the upcoming basketball postseason would be altered due to rationing. The story was picked up by various newspapers across the Midwest.

“The association’s Representative Council last night stressed need for following a ‘principle of minimum travel’ in basketball play this winter and voted to dispense with the annual Lower Peninsula finals,” instead opting for a modified layout. Initial conversation related to a plan calling for sectional meets with the possibility of naming titles in the northern half of the Lower Peninsula, and in both the southern and eastern areas. An appointed basketball committee was also to consider combining enrollment classifications wherever necessary to localize tournament play.

From 1932-1947, inclusive, separate Lower and Upper Peninsula basketball champions were determined. The Upper Peninsula Athletic Committee announced a similar plan at its meeting in January of 1943. The committee expected to present winners of the U.P. events with certificates instead of the customary trophies due to shortage of materials prompted by the war.

According to a survey of its 40 member state associations by the National Federation of State High School Associations, Michigan was one of only four states, including Maine, Montana and Nevada, to eliminate naming basketball state champions come the winter of 1943, “since the distances within those states are too vast or transportation facilities are too limited. The same will prevail in track contests.”

By mid-January, the MHSAA had polled its membership, and approximately 95 percent of the state’s high schools indicated a desire to participate in the replacement tournaments pitched by the Association. After examining the logistics, the plan previously discussed was modified. The Association then identified 51 Lower and 11 Upper Peninsula sites, based on availability to host the tournament and geographic suitability. The competition would run for two weeks, and end with what had previously equaled District championship contests.

By mid-January, the MHSAA had polled its membership, and approximately 95 percent of the state’s high schools indicated a desire to participate in the replacement tournaments pitched by the Association. After examining the logistics, the plan previously discussed was modified. The Association then identified 51 Lower and 11 Upper Peninsula sites, based on availability to host the tournament and geographic suitability. The competition would run for two weeks, and end with what had previously equaled District championship contests.

In the meantime, the annual swim championships were reduced to a one-day meet. Hosted at the University of Michigan, the meet would tax the endurance of individual swimmers, “since officials … decided to conduct semi-final events additional to the customary qualifying trials and finals.” That meant a swimmer entered in two events could compete six times during the day, with qualifying events in the morning, semifinals in the afternoon and finals swum at night. Perennial powers Battle Creek Central and Ann Arbor University High emerged as champions.

“The war to date has proved one thing conclusively – athletics in all schools must go on, for they serve to properly condition our young men for the bigger task ahead,” said MHSAA interim director Smith, speaking at an “annual football and basketball ‘bust’ for Lakeview High School” in Battle Creek in February 1943. Smith had served as principal at the high school for 14 years before taking over at the MHSAA. He “expressed regret” that the MHSAA had altered the various formats of the annual championships. According to coverage of the gathering in the Battle Creek Enquirer, “he intimated that it, along with all other forms of statewide competition, would be restored before another school year begins.”

Continued Chaos

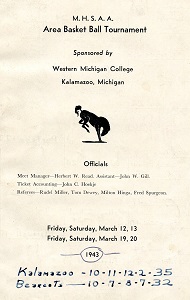

The cities of Lansing and Kalamazoo played host to the most contingents, with 25 teams across the four enrollment classifications playing games at recently completed Lansing Sexton – the rechristened Lansing Central High School – and the Lansing Boys Vocational School. A total of 23 schools squared off at Western Michigan College of Education (now Western Michigan University).

As previously stated, transportation considerations meant some schools played above or below their normal classification to make things work. Ecorse, normally a Class B school, battled in the Class A tournament hosted at Dearborn Fordson. Benton Harbor, with Class A enrollment numbers, competed in the Class B tournament played across the St. Joseph River at St. Joseph High School instead of at the Kalamazoo Area tournament against similarly-sized schools.

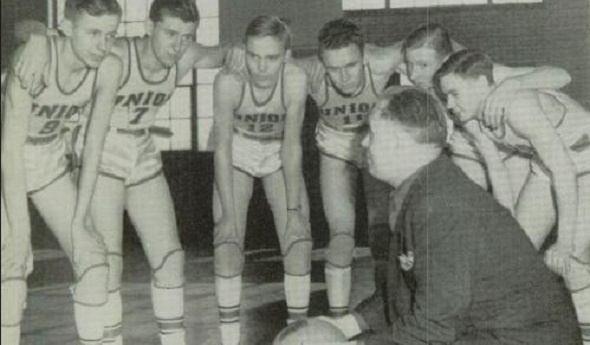

A total of 128 area titles were awarded across the state’s two peninsulas. Decatur, the Class C state champion in 1942 with a 25-0 record, was the only team titlist to repeat in 1943, emerging with one of the “Area” crowns and extending its streak of victories to 41 consecutive. Also among the winners was Grand Rapids Union, a “cellar team in the regular season.”

“Although Union stood seventh in the city tally, the Red Hawks won the Area Tournament Crown in three smashing, spine-tingling battles,” stated the sports editor in the 1943 Aurora - Union’s yearbook. “In fast games the Hawks overcame Catholic and beat the Creston Bears … as well as whipping Davis Tech for their final victory.”

In April, the MHSAA confirmed that competition would end with area, city or conference meets in track, and again in tennis and golf, because of transportation, participation issues, and the “prospects of closing of some of the schools early.”

Various fans and media members grumbled about the unsatisfying conclusion to the prep sports calendars.

Hope

The coaching ranks were heavily hit by the war, as numerous mentors were tapped by the armed forces to lead physical fitness programs. Despite initial concerns, few “of the state’s 400 football-playing prep schools” dropped the sport come the 1943-44 school year. As it would turn out, because of the travel constraints, attendance increased as more and more sports fans turned to high school competition for entertainment.

Smith stated in October that he had “yet to find anyone who is definitely against bringing the (basketball) championship tournament back to life. There seems to be overwhelming sentiment in favor of the revival. The schools right-about face on the state cage classic which annually drew 700 prep teams and 11,000 players is explained by the fact coaches now feel the federal government is strongly in favor of any attempt to encourage or extend athletics. Last year schoolmen were not certain what the government’s attitude on sports would be and were hesitant about continuing athletics in pre-war style.”

Only 258 of 614 schools replied to a questionnaire about restoring the winter basketball state championships, but 73 percent of respondents were in favor of such, and in December, the Representative Council voted to resume the final rounds of the tournaments.

Only 258 of 614 schools replied to a questionnaire about restoring the winter basketball state championships, but 73 percent of respondents were in favor of such, and in December, the Representative Council voted to resume the final rounds of the tournaments.

Born October 1918 in St. Johns, Michigan at the peak of the “Spanish Flu” pandemic, Hal Schram was a 25-year-old sports reporter for the Lansing State Journal when he covered the restart.

“State championship basketball and track competition once more became a part of (the) Michigan high school athletic program when the Representative Council of the MHSAA voted to reinstate these two state-wide tournaments after a suspension of one year,” he wrote.

According to Schram, “It was believed that student working hours, transportation, scarcity of balls and general lack of interest” still necessitated cancellation of golf and tennis tournaments for the year. Conduction of a swimming championship was left “in the hands of a committee representing schools which sponsor the sport … subject to the approval of the representative committee.”

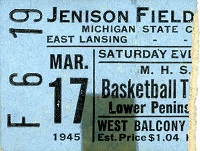

Plans were to return the final rounds of the basketball tournament to Jenison Field House on the campus of Michigan State, which had hosted those rounds from 1940-42. However, the facility was in use by Army trainees for a physical fitness program.

“We would like to have the finals staged here very much,” said MSC athletic director Ralph Young, “but our obligations to the army come first.”

“Despite the hitch, the executive committee opted to stay in Lansing, playing Class A and C semifinal contests at the Boys Vocational School fieldhouse, and Class B and D semi games at Sexton High School. Finals were held at the Vocational gym.

“Fifty-five hundred spectators jammed their way into every nook and cranny of the Boys Vocational school fieldhouse last night to see four high school teams (Saginaw Arthur Hill, Marshall, Lansing St. Mary, Benton Harbor St. John) win championships in the Lower Peninsula tournament finals. With all seats taken almost before the first game started, the big floor was completely encircled by people sitting and standing before the finish,” wrote State Journal sports editor George S. Alderton. “By 6 o’clock, when the Class D game started, all seats in the side bleachers had been filled and most of the end bleachers were gone. The last vacancy was occupied before the Class C game started at 7:15 o’clock and from that time on, those who came either stood or seized a seat left by some departing fan. In many instances two sat down when one departed. Corners of the court were seething masses of humanity …”

United Press International wire reports indicated that 8,500 in total saw the Finals, as fans shifted in and out of the venue in support of the participating teams. “Some people had to be turned away at the finals,” said Smith, “and that certainly shows that people need and want this kind of relaxation.” The previous three Finals at MSC had drawn between 6,000-7,000 fans, while the 1939 Finals at I.M.A in Flint drew 5,000 and the 1938 event at Grand Rapids Civic Auditorium saw 6,000 attend.

“Lighting was so poor in the press box Friday night for the semi-finals,” added Alderton, “that workers came equipped with candles for the finals on Saturday night and propped them against their typewriters.”

Ishpeming hosted the Upper Peninsula Finals, as Escanaba, Crystal Falls, Channing and Amasa swept titles, respectively, in Classes B, C, D and Class E – the state’s smallest classification, reserved only for the smallest U.P. schools based on enrollment.

“Only complaint,” noted the Marquette Mining Journal, “was from those who couldn’t get in or were caught in a jam of fans seeking general admission seats. … Probably another 100 to 200 could have been accommodated if they were permitted to sit on the floor all along the court lines, but this would have been hazardous to players and fans …”

(The Lower Peninsula finals returned to Jenison in 1945 – where they stayed, uninterrupted, through 1970 – and were played before 7,833 spectators that first season back. Locals were delighted as they watched Lansing Sexton top Benton Harbor’s undefeated Tigers, 31-30. Michigan Governor Harry Kelly “personally presented the Class B championship trophy to Sturgis Capt. Tom Tobar, congratulated Capt. Larry Thomson of East Lansing and then shook hands with the captains of the Class A contest before the game started.”)

(The Lower Peninsula finals returned to Jenison in 1945 – where they stayed, uninterrupted, through 1970 – and were played before 7,833 spectators that first season back. Locals were delighted as they watched Lansing Sexton top Benton Harbor’s undefeated Tigers, 31-30. Michigan Governor Harry Kelly “personally presented the Class B championship trophy to Sturgis Capt. Tom Tobar, congratulated Capt. Larry Thomson of East Lansing and then shook hands with the captains of the Class A contest before the game started.”)

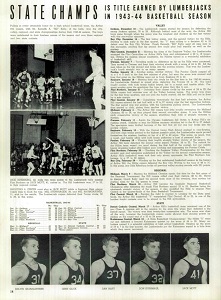

In mid-May, “some 800 Michigan prep trackmen, survivors of 40 regionals at 10 centers” headed to Michigan State College to determine statewide champs. Only Kalamazoo in Class A and Birmingham in Class B held the chance to “repeat” as team champions. Instead, Saginaw Arthur Hill capped a stellar sports year, earning its first Class A team track title to go with its recently-earned basketball crown. (Earlier in the school year, the Lumberjacks also had opened their own football field.)

East Grand Rapids earned its second track title, grabbing the Class B crown. Fowlerville and Glen Arbor Leelanau brought home titles in Class C and D, respectively.

All sports – including golf and tennis which had gone three years without competing in a true state title round – returned to their original formats with the start of the 1944-45 school year.

In May 1945, Germany surrendered to the Allies, followed by Imperial Japan’s surrender, announced in August.

Participation in prep sports and attendance numbers would explode across the state and the nation in the coming years, tied to multiple factors, including, of course, the baby boom that followed World War II.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) Grand Rapids Union was among "Area" boys basketball champions in 1943. (2) Lewis Forsythe, left, and Charles Forsythe were among leaders during the MHSAA's first decades (3) The Saginaw Arthur Hill yearbook for 1944 tells of fitness training undertaken by students. (4) Julian W. Smith served as interim MHSAA executive director while Charles Forsythe was serving in the military. (5) Flint Northern's Bill Hamilton earned all-state honors in 1942. (6) Western Michigan College was among hosts of 1943 Area tournaments. (7) Arthur Hill's yearbook celebrates the 1943-44 boys basketball championship. (8) Basketball Finals returned to Jenison Field House in 1945. (9) The MHSAA paid tribute to World War II veterans in its 1945 Basketball Finals program.

Hayes Jones: Olympic Hero Built in Pontiac

April 30, 2019

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

His mother was going to name him Kelly, chosen to honor her brother who had passed away. But before the birth certificate would be filed at the county seat for Ethel’s newborn son, there was a change of plan.

He was born in August of 1938 in Starkville, Mississippi, into a world at unrest. Not yet officially at war, it would be soon.

Ethel’s father had a different suggestion. His daughter had another brother, who served in the Navy. If something were to happen to her brother, there would be no one else to carry on the family surname. With that, it was decided.

Instead, the child’s first name would be Hayes.

At the age of 80, Hayes Jones is happy to share the details of his life. Especially when the conversation offers the occasion to remember the people and places that most impacted his being. The conversation, as it always has, includes stories about mentors. These are the people who he will never forget.

The names and the stories are certainly not new. Many have appeared, in some form, in newspaper interviews from five, 15, 50, or 60 years ago. They are told with joy and admiration.

He speaks in measured tones, at a moderate and deliberate pace.

"I grew up a kid with a nervous condition, bad ulcers in junior high and I stammered," he told Marvin Goodwin of the Oakland Press in 2014. "I couldn't speak a sentence without stuttering."

“I still have that, if I get overly excited,” said Jones, speaking on his cell phone while on a recent visit to metro Detroit.

For the past 10 years, Jones has lived in Atlanta, Ga., and spends most of his time there. But he lived in and around Pontiac for years while working in and near the Motor City. He still has a home there and returns to visit with family.

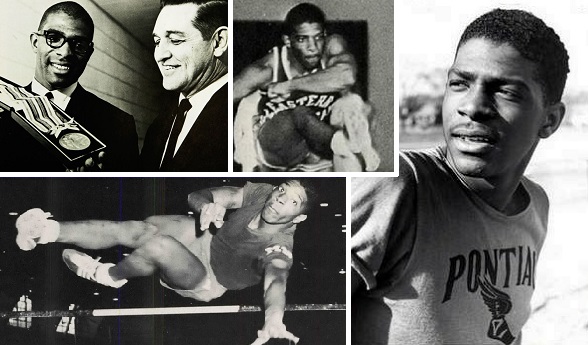

Academics nearly derailed what was to come, but with a willingness to listen, absorb, then act, he would become a state track champion. At the age of 22, he held three world records and was an Olympic medalist. By 26, he would earn gold.

The spring of '55

Jones’ name first surfaced before a statewide audience in early April 1955 in a stringer’s report to the Detroit Free Press.

“Pontiac completely outclassed 11 other Class A foes here Friday night to win its first Arthur Hill-Saginaw High School invitational indoor track title at Central Michigan College’s fieldhouse. … Coach Wally Schloerke’s balanced outfit won six of the first 10 events.

“Leading the way for Pontiac was Willie Wilson who captured the high and low hurdles. Other Pontiac winners were Hayes Jones in the broad jump and Morris Jackson in the 440. The Chiefs also won both the medley and four-lap relays.”

“The final score of the winners more than doubled the points of runner-up, Flint Northern, who tallied 30½ points to the winner’s 69½ points,” stated the Traverse City Record Eagle in its extensive coverage of the event. Jones, a junior, had also tied for first, with teammate Hudson Ray, in the high jump, finished second in the 65-yard low hurdles and fourth in the high hurdles.

Two weeks later in the Free Press, sportswriter Hal Schram noted that Pontiac had won its second straight dual meet, overwhelming Dearborn Fordson, 84 1/3 to 24 2/3. “Hayes Jones won two events outright and tied for a third in piling up 14 points. He won the high hurdles in 15.4 seconds, the broad jump at 19 feet 2 inches and tied in the high jump at 5 feet 11 inches.” According to Schram, the Chiefs were already being “touted as the team to beat for Class A track honors.”

Competing in the ultra-competitive Saginaw Valley Conference, track success was relatively new to PHS. With the assistance of Ray Lowry, who previously served as Pontiac’s track coach, Schloerke’s Chiefs had finished as runners-up to the Class A state title in the springs of 1952 and 1953.

In the Regional at Ypsilanti, Pontiac qualified 19 athletes over 11 of the meet’s 13 events. Jones won the high hurdles and broad jump.

“Herb Korf, veteran coach at Saginaw High whose teams won seven (track) State titles in 10 years (1945-1954) admits he never had a squad with the depth and balance of this Pontiac powerhouse,” wrote Schram in his preview of the 1955 state meet. “The Chiefs won’t win many first places Saturday but will pile up the seconds, thirds and fourths. Willie Wilson and Hayes Jones in the hurdles and Freeman Watkins in the broad jump have the best chances of winning events.

“’It appears to be a battle for second place,’ is the begrudging forecast of Bill Cave, Flint Northern coach. who dislikes playing second fiddle to anyone.” (Cave and Flint Northern won MHSAA Class A titles in 1950 and 1953 and then ended 1954 second to Saginaw. The Vikings would then finish as Class A runners-up in each of the next six years before earning another title in 1961.)

“’It appears to be a battle for second place,’ is the begrudging forecast of Bill Cave, Flint Northern coach. who dislikes playing second fiddle to anyone.” (Cave and Flint Northern won MHSAA Class A titles in 1950 and 1953 and then ended 1954 second to Saginaw. The Vikings would then finish as Class A runners-up in each of the next six years before earning another title in 1961.)

As predicted, Pontiac grabbed an easy victory at the Class A meet, hosted at Michigan State’s Ralph Young Field. The Chiefs scored 51 13/14 points to Flint Northern’s 17. Jones alone racked up 17 points, winning the 120-yard high hurdles with a record time of 14.5 seconds, shaving a tenth of a second off the mark held for 14 years by Jackson’s Horace Smith. Jones also won the broad jump and finished second to Benton Harbor’s Don Arend in the low hurdles.

Alex Barge and Hudson Ray tied for high jump honors, while Bill Douglas won the 880 for the Chiefs.

“Pontiac’s only ‘muff’ of the day came in the final 880-yard relay,” said Bob Hoerner of the Lansing State Journal, “when a dropped baton by the already-champions kept the Chiefs from getting more points.”

At season’s end, this 1955 track team was quickly identified as the greatest in school history.

Learning to fly

While he was born in Starkville, Hayes Jones was built in Pontiac during an era of prosperity – when the city held a single public high school and employment was strong. His father, Jesse, had followed a younger brother to Michigan for work. Saving enough money after a couple of months, he called for his family to join him. Hayes was 3.

Jones never failed to credit those who helped when discussing the global athletic success that would come.

In a Free Press article from 1996, he recalled his instruction. “I had a good hurdling coach, Ray Lowry … and from what he taught me I’d visualize what I was supposed to do,” said Jones. A record holder at Toledo Scott High School, Lowry was one of the top pole vaulters in the nation while at Michigan Normal (today Eastern Michigan University) during the mid-1930s.

“Mr. Lowry taught me everything I knew about hurdling,” said Jones, when Lowry’s name was mentioned. “When I went to college my coach was a distance expert, but he didn’t know much about hurdling. As a freshman in Pontiac, I ran hurdles but I was very short. Most of my peers were taller and moved much faster than me. But Mr. Schloerke and Mr. Lowry saw my determination and said, ‘Let’s keep him on the team.’ I asked if I could take home a hurdle to practice with during the summer. I lived a mile and a half away. Mr. Lowry said ‘I’ll leave two or three out for you. You can practice with them after you deliver your newspapers.’ So every morning I’d deliver the Detroit Free Press and I would then head over to Wisner Stadium to practice.

“One morning this gentleman was driving past the stadium, and decided to stop. His name was Charlie Irish and he was a recreation supervisor for the city of Pontiac. I guess he’d drive by every morning and see this kid practicing. On this particular morning he stopped, and then every morning he would come.”

Whenever the ‘kid’ knocked down hurdles, Irish would pick them up and put them back in place.

Whenever the ‘kid’ knocked down hurdles, Irish would pick them up and put them back in place.

“Charlie and his wife moved to Sun City after he retired. After college, I would fly to Arizona to thank him every year for giving up his time. There’s a large cemetery off Woodward between 13 and 12 Mile Roads, (where he’s buried),” said Jones, continuing. “Whenever I’d find myself there, I’d look to my right and remember Charlie.”

A fourth figure from Pontiac also loomed large in shaping Jones.

In the fall of 1955, after serving 13 years as principal at Pontiac Eastern Junior High, Francis Staley assumed the role of principal at Pontiac High School. He would remain in the role until the fall of 1967. His new job led to a conversation with the school’s budding track star.

“You have done your homework,” Jones said, laughing. “Yes, that was Principal Staley. He was the one from a personal standpoint that put me on the right track from an academic point of view.

“When he arrived at the high school, he called me to his office. I didn’t know what was going on. I thought he just wanted to meet a state champion,” Jones added, chuckling at the thought. “He had a folder on his desk. ‘I just want to let you know, no student at Pontiac High School can participate in extracurricular activities without passing grades. It appears you are right on the border.’”

Jones told Marilyn Daley of the New York Daily News about the incident for a feature in 1968. At 29, he had recently been named commissioner of recreation for New York City’s “new super-agency, the Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs Administration,” working toward giving kids and adults, regardless of income, opportunities for recreation 12 months a year.

“Hayes, you can’t continue in sports with these grades. Do you want to run or do you want to study?” asked the new principal.

“He was going to take me off the team," Jones explained. "Track and field was my whole life.

“That was the turning point of my life,” said Jones some 60 years later, reflecting on that summit and the impending consequences. “I hit the books. If it weren’t for Principal Staley, I wouldn’t have attended college.”

New-found focus

The 1956 track season would cement Jones’ standing as the greatest track athlete in Pontiac school history.

In March, at the Huron Relays, an indoor event hosted at Eastern Michigan’s recently opened Wilbur P. Bowen Fieldhouse, Jones picked up where he left off, winning three events while finishing tied for a fourth. It was an impressive performance to kick off the season.

In early April, Jones again starred at the Saginaw-Arthur Hill Indoor Invitational event at Central Michigan, setting new meet marks in the broad jump and high jump (tying with teammate Hudson Ray). He really opened eyes with a 7.8 time in the 65-yard high hurdles. “The recognized college time in the nation for that distance is 7.9,” noted the Record-Eagle, “so fans can see that he really was moving.”

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, concern was expressed about one athlete dominating prep meets in Michigan.

“There’s considerable agitation among prep track coaches to alter the point system in the state championships,” reported Bill Frank, future sports editor for the Battle Creek Enquirer. “Last year, for instance, Hayes Jones of the Class A championship Pontiac High team scored (the same number of points as) the second place school. … Many coaches feel that relay teams should count double in points, such as in the state swim meet. … Doubling points in relays would offset one school coming up with one outstanding athlete who could win the title by himself, such as Jones. … Also it’s felt it isn’t fair to give an individual seven points for a first place when an entire relay team of four runners can earn no more points as a group for winning.”

That April 21, for the first time in school history, Pontiac sent 17 athletes to compete in the prestigious Mansfield Relays in Ohio. Today the event is known as the Mehock Relays, renamed after the event’s originator, Harry Mehock, in 1972.

“Pontiac’s individual standout is Hayes Jones … who could well become Michigan’s all-time star prep hurdler,” wrote Ed Ackley of the Flint Journal, a week prior to the event. “Pontiac coach Wally Schloerke says he isn’t taking his club to Mansfield with any great hopes of winning the team title. ‘I just want to give the boys a good workout against stiff competition,’ he points out.”

“Pontiac’s individual standout is Hayes Jones … who could well become Michigan’s all-time star prep hurdler,” wrote Ed Ackley of the Flint Journal, a week prior to the event. “Pontiac coach Wally Schloerke says he isn’t taking his club to Mansfield with any great hopes of winning the team title. ‘I just want to give the boys a good workout against stiff competition,’ he points out.”

But seven days later, for the first time in the Relays’ 25-year history, the Mansfield trophy “made its first trip outside the confines of Ohio.” It headed north to Michigan, thanks to “a sterling performance by lithe Hayes Jones,” said Fred Tharp, sports editor for the Mansfield News-Journal in a front page story.

Jones piled up 16 points, winning the 120-yard high hurdles and the broad jump, while placing “second in the 180-yard low timbers. His winning broad jump of 22 feet, 11¾ inches was just 3¼ inches behind the record set by Cleveland’s Jesse Owens in 1933. Jones had equaled the 180-yard low hurdle record of Bill Whitman of Cleveland East Tech in the morning semi finals. Whitman had run 19.4 in 1952.”

“Jones’ two firsts were the only wins authored by Pontiac but the Michigan School took four seconds, two thirds and a fifth” as the school racked up 34½ points. “Jones’ 16 points outscored 92 teams in the huge field.”

(Over 60 years later, Jones is one of only seven Mansfield/Mehock winners who went on to become an Olympic champion.)

A week later, Pontiac won its second consecutive Class A championship at the Central Michigan College High School Relays.

“In the 16-year history of this event the weatherman has seldom co-operated. Saturday was no exception,” stated the Free Press in its coverage of the gathering. “Weekend rains and the pounding feet of nearly 3,000 schoolboys, turned the oval into a quagmire. Despite these conditions, Jones had another fine day.”

The versatile athlete won three events, setting a meet record in the 120-yard hurdles at 14.9 on a rain-drenched track in near-freezing temperatures.

At the Class A Regional at Ypsilanti, Pontiac cruised to a record-shattering victory, scoring 97½ points and 12 firsts across 15 events, and again was expected to dominate the MHSAA Class A meet. To no surprise, Jones starred.

“Already the possessor of the state high hurdles record of 14.5, set last year, Jones bettered it last week for the third time. He cleared the posts at 14.3 (at the regionals) – only three-tenths off the national high school mark of 14,” stated The Associated Press in its preview to the upcoming state championship. Schloerke was quoted as saying that Jones was a “definite Olympic future prospect”.

On May 21, at the Class A and D track and field championships hosted at University of Michigan’s Ferry Field, “Hayes Jones made all those fabled track performances of his official,” stated the Free Press. “The 160-pound Pontiac High senior set two of the six records established, won three firsts and led the Chiefs to their second straight Class A track and field championship. Pontiac rolled to a record 61 points by winning six events and scoring in 10 of the 13 on the program.”

It was the 12th Class A championship by a Saginaw Valley Conference track team in 13 years.

Jones bested a 20-year old mark in the broad jump by more than nine inches (previously held by Lansing Central’s Ted Tycocki), with a leap of 23 feet 8 7/8 inches. He topped his own record in the high hurdles with a mark of 14.4, “won the lows in 19.4 and anchored the winning Pontiac 880-yard relay team for a personal contribution of 19½ points … other Pontiac firsts were won by Hudson Ray in the high jump, with a leap of 6 foot 3 3/8 inches and Bill Douglas, who captured his section of the half mile in 1:59.7.”

“The Pontiac track team should be recorded as the most powerful thinclad team in P.H.S. history - surpassing, if possible, even the undefeated State Championship squad of 1955,” wrote the sports editor of the 1956 Pontiac High School yearbook. Balance and depth, along with individual record-breaking performers, accounted for Coach Schloerke’s ‘dream team.’”

Eastern Michigan and national fame

The conversation with Principal Staley, and Jones’ decision to act, paved the way for life after high school. It was Lowry who suggested that Jones attend his alma mater, Eastern Michigan.

There was interest from larger schools that offered track scholarships. But an athletic scholarship didn’t apply at Eastern.

“We are forbidden to do so by our administration. We have absolutely no scholarships available to athletes as such,” said Eastern track coach George Marshall at the time. Eastern, along with Central Michigan, competed in the Interstate Intercollegiate Athletic Conference with five schools from Illinois.

“My parents said, ‘You’re going to school to get a college education, not to just run track.’ I washed dishes and mopped floors to help my parents pay for college,” recalled Jones. “You had to get in based on academics. I think I would have gotten lost at a bigger school. At Eastern – teachers gave you one-on-one attention. They’d invite you over for dinner. I needed that.

“Back then all the boys had to serve one year in ROTC at Eastern. For some reason, I couldn’t stand at attention for any length of time – I would always get regular demerits. Finally, they said, ‘We’re sending you over to the infirmary to find out why.’ There they found out my left leg was three quarters of an inch shorter than my right. They made me exempt from ROTC, and I was told ‘Go run track.’”

At Eastern, Jones joined 17 returning lettermen on the track team. Standing 5-foot-10, Jones was small for a hurdler, but he quickly made his presence known.

In the opening meet of the winter indoor season, a 62-42 loss to Marquette University, Jones stood out, tying the Hurons’ 65-yard low hurdle mark with a winning time of 7.4 seconds. He also finished first in the high jump and broad jump. By the end of his freshman indoor-outdoor season, he had competed in 58 events and had captured 49 firsts.

In a 54-50 victory over reigning Big Ten champion Indiana in March of 1958, Jones, now a sophomore, tied the world’s record in the 60-yard dash. He also set a new American record in the 70-yard low hurdles and tied the U.S. mark in the 70-yard high hurdles. Instantly, he was thrust to the “forefront of American indoor hurdles.”

In June, he was invited on a trip with a U.S. State Department-sponsored track team that toured Belgium, France and Italy. Again, he absorbed advice and direction from coaches and peers.

Dave Sime, a great Duke sprinter, was on the trip and among those he credited. (Sime later would win a silver medal in the 100 meters at the 1960 Olympics in Rome).

Dave Sime, a great Duke sprinter, was on the trip and among those he credited. (Sime later would win a silver medal in the 100 meters at the 1960 Olympics in Rome).

“I had been dizzy starting … sometimes I’d use my arms right but often I was wrong. He showed me how to use them properly and I’ve been getting away good,” said Hayes in March 1958 after surprising track followers with a victory in the 60-yard hurdles at the National Amateur Athletic Union Indoor event in New York.

An injury suffered in December 1958 of his junior year received play across newspapers around the Midwest.

“I broke the training rules to play basketball and didn’t get caught until I broke my ankle,” said Jones, recalling the time in the New York Daily News article.

“It was a hairline fracture but Eastern had them put a full cast on me. I guess they didn’t want me to do any more damage,” Jones remembered, humored by the memory.

He was back in full form by the end of January 1959, winning two events for the second time in a row at the Michigan AAU track meet at Ann Arbor, including an 8-second flat in the 65-yard high hurdles – a tenth of a second off the world record. By his senior year, he was a national track celebrity, winning the 110-meter high hurdles at the Pan-American games in September 1959, then equaling the world record in the 60-yard indoor high hurdles at the end of January 1960 at the Millrose Games in New York. The news of his record was covered coast-to-coast.

In February, in back-to-back meets staged in Philadelphia and New York, he became the first in history to win both sprint and hurdle events in major indoor meets. Later in the month, he edged Lee Calhoun (the 1956 Olympic gold medalist in the 110-meter hurdles from Gary, Ind., and North Carolina College) in the 60-yard high hurdles at both the 72nd National AAU championships at Madison Square Garden and at the Knights of Columbus meet in New York. In Cleveland in March at the Knights of Columbus meet, he again topped Calhoun in the 50-yard high hurdles, lowering the world indoor mark to 5.9 seconds in the race.

A rivalry was formed. “I had the speed, but not the endurance,” stated Jones, recalling his dominance in the shorter indoor races but Calhoun’s success in the longer outdoor events. “I was leading up to the sixth or seventh hurdle, then I’d hear him coming.”

An Olympic berth

Jones continued to cause I.I.A.C. meet records to fall like dominoes when the outdoor season arrived at Eastern. In July, he earned a place on the U.S Olympic team at the trials at Stanford in Palo Alto, Calif., finishing third behind Calhoun by one tenth of a second, and Willie May (Big Ten hurdles champion at Indiana University) at 13.5 in the 110-meter hurdles. Public fundraising efforts began immediately in Pontiac to raise money to send his parents to Rome to watch their son compete in the Games of the XVII Olympiad. The three – Calhoun, May and Jones – finished in the same order in Rome in September sweeping gold, silver and bronze for the U.S.

After college, Jones accepted a teacher-coach position at Detroit Denby High School while training for the 1964 Olympics. When told by Olympic officials that accepting a coaching stipend could affect his amateur status, he soon transferred to Tilden Elementary in Detroit.

By February 1964, he had posted 50 straight indoor wins, dating back to 1959.

Asked why he preferred indoor racing, Jones told Sports Illustrated, “I’m only 5 feet 10 and outdoors everybody’s bigger than I am. When I get indoors, though, the spring in the boards and the spring in my legs make me 7 feet tall and I’m bigger than anybody.”

Still, there comes a point when experience is no longer a runner’s friend. Despite the success, Jones knew the 1964 season would be his last.

”Now I’m old – mentally. I’ve done everything a man can do as an athlete, and now I’m just repeating,” he told longtime sports journalist Bud Collins of the Boston Globe that February, announcing his plans to retire after the track season. “I won’t be able to keep the competitive edge much longer.” He still had one goal he wanted to meet: “I want to end my career with a gold medal.”

At the All-Eastern Invitational in Baltimore at the end of the month, he grabbed his 55th consecutive indoor victory, flashing “over the 60-yard high hurdles in 6.8 seconds.” The time shattered his previous indoor world record by one-tenth of a second. With the accomplishment, he stepped away from indoor competition.

In July 1964 at preliminary U.S. Olympic trials hosted as part of the World’s Fair in New York, Jones earned his place with the U.S. team. In October, just prior to the Tokyo games, he reminded the press of his retirement plans. “The only way I can go from here is down,” said Jones, now 26 years old. “I’ve sacrificed two months’ salary to come here. I came because I thought I could win. We’ll know pretty soon now.”

Jones qualified for the medal race, finishing second in his 110-meter hurdle preliminary round heat and third in his semifinals race. But he recognized an issue.

“… When I got to Tokyo I realized my training had not been right, that I had not done enough speed work,” Jones told Sports Illustrated in 1968, recalling the moment. “I was not fast enough between the hurdles. … I remember on the last day running up and down in the tunnel under the stadium, trying somehow to develop speed at the last minute. … In that tunnel a coaching friend, Ed Temple (head women’s track and field coach for 44 years at Tennessee State and head coach of the Women’s U.S. Olympic track team in both 1960 and 1964) came up to me and said, ‘Listen, Hayes, forget about your speed. Don’t worry about it. Just run between the hurdles. Just run.’”

“The only thing Hayes Jones recalls from the rainy race,” wrote Kathleen Gray, referring to the championship battle in a 2004 Free Press article, “was lunging toward the tape. It took longer in those days to figure out who crossed the finish line first, especially with the photo finish of the three top contenders …”

“The only thing Hayes Jones recalls from the rainy race,” wrote Kathleen Gray, referring to the championship battle in a 2004 Free Press article, “was lunging toward the tape. It took longer in those days to figure out who crossed the finish line first, especially with the photo finish of the three top contenders …”

Depending on the source, it took 30 minutes – or was it more – for officials to declare a winner.

“It seemed like 45 minutes before the pictures were in and the lights began to flash on the scoreboard,” Jones said to SI. “Then it came: ‘First place, J…O…N…E…S…’ I can’t tell you the feeling, the thrill of it.”

Fellow countryman Blaine Lindgren finished second, while Anatoly Mikhailov of the Soviet Union ended the race third.

Jones had won his desired gold medal. And then, he gave it away.

Olympic hero comes home

That November, upon his return, Jones presented his Olympic gold medal to the youth of Pontiac during a ‘Salute to Youth’ rally at Pontiac Northern, the city’s newest high school. It still is on display at Pontiac City Hall. The donation was meant to “inspire kids to reach for their dreams,” said Jones.

“When I matriculated to the fourth grade, our principal gathered us together and said, ‘Now that you’re in the fourth grade you can participate in sports.’ The Kiwanis Club sponsored basketball, football and track,” Jones said.

“Because of that, I was able to find my passion. If not for the Kiwanis Club, I doubt I would have been able to find that. What made Pontiac so great was their belief in giving their time. A great community starts with volunteers.”

Today, there are two medals on display.

“The bronze, I had originally donated to the Detroit Children’s Museum under the Detroit Public Schools for permanent display but each time I went to visit, it was in storage. After three times reminding them that it should be on display, I asked for it back and donated it to the city of Pontiac. So now, kids making field trips to city hall will see two Olympic medals laminated and encased in the wall when they visit.”

As he told SI in 1968:

“It wasn’t the medal that mattered, don’t you see? It was the experience.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

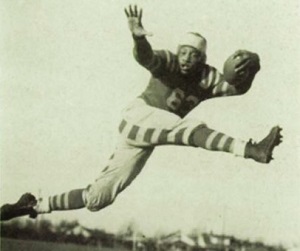

PHOTOS: (Top) Clockwise from left: Hayes Jones presents his Olympic medal to Pontiac mayor William H. Taylor in 1964, Jones leaps a hurdle while at Eastern Michigan, Jones at Pontiac High and Jones goes over the high jump bar while at EMU. (2) As noted, Jones and Willie Wilson warm up before a Pontiac practice. (3) Jones with his Pontiac coaches in 1956. (4) Jones, far left, accepts trophies at the Mansfield Relays. (5) Jones on the cover of his View-Master series on physical fitness. (6) Jones sprints to the finish of his Olympic gold medal win. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)