The Last Time MHSAA Finals were Canceled

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

April 27, 2020

Historians trace the start of World War II to German dictator Adolph Hitler’s decision to invade Poland on September 1, 1939. The Empire of Japan’s involvement in the war became effective in September 1940 with the signing of the Tripartite Pact.

Until December 7, 1941, the United States avoided official involvement, declaring themselves “a neutral nation.” Then came Imperial Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor.

A labor shortage caused by World War I had taken out spring high school sports in Michigan in 1917. As noted in the Second Half article, “1918 Pandemic, WWI Threatened High School Sports,” the global spread of a devastating strain of influenza interrupted the football season in Michigan. Prep athletics would roar through the 1920s and survive the Great Depression before seeing another interruption.

That next disturbance had nothing to do with war’s insatiable desire for manpower. Rather, it was because of tires.

“When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, rubber instantly became the most critical strategic material for making war,” wrote Stephen W. Sears in the October/November issue of American Heritage magazine in 1979. “Nine-tenths of the nation’s rubber came from the Far East, and it was painfully evident that nothing would now stop Japan from cutting off that source.”

Americans consumed nearly two-thirds of the world’s production of rubber. With only about a year’s worth of material on hand, “Just four days after Pearl Harbor a freeze was put on the sale of new passenger-car tires,” stated Sears, “and on December 27 tire rationing was authorized, to go into effect early in January, 1942. Sales of new cars also were halted.”

The MHSAA

The Michigan High School Athletic Association arrived in December 1924. It replaced the old Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association which had served Michigan for 15 years.

The organization’s primary purpose was to standardize, interpret and administer rules, educate and guide officials, and regulate student eligibility within prep sports in Michigan. By the 1940s, it had evolved into an association that also managed postseason tournaments, designed to identify state champions in specific sports: swimming, cross country, golf, tennis, track, and the sport sponsored by the most high schools in the state, basketball.

“The old MIAA had taken over the regulation of basketball tournaments in 1920. This had been done as a service to the schools and especially as a means of eliminating evils inherent in the invitational tournaments (that were hosted by various colleges around the state and the midwest),” wrote Lewis L. Forsythe in his book, Athletics in Michigan High Schools, recalling the first 100 years of prep sports in the state.

“The old MIAA had taken over the regulation of basketball tournaments in 1920. This had been done as a service to the schools and especially as a means of eliminating evils inherent in the invitational tournaments (that were hosted by various colleges around the state and the midwest),” wrote Lewis L. Forsythe in his book, Athletics in Michigan High Schools, recalling the first 100 years of prep sports in the state.

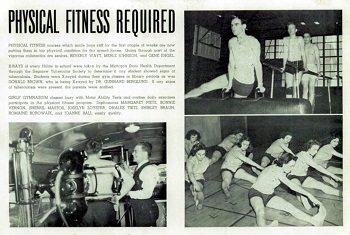

“In the last days of February 1942,” multiple Michigan schoolmen were in San Francisco to attend the annual meetings of Secondary School Principals, Superintendents and the National Federation of State High School Associations. “We were well aware that many of our boys in school would have to offer themselves in the service of their country,” noted Forsythe in his publication. “We fully realized that the quality of that service and, indeed, their own survival might well depend quite as much on their physical fitness as on their intellectual and spiritual resources. It was under those circumstances that we determined so to modify the emphasis of our athletic program as to make the largest possible contribution to the war effort. We recognized that the need in Michigan could not be met by our organization alone, and we therefore determined to encourage a general enrollment of all school groups in a united effort for promotion of physical fitness.”

Because of the “scarcity of tires and automobiles,” in April 1942 the MHSAA announced plans to curtail their upcoming annual golf and tennis events, eliminating a state championship round. Instead, the seasons were concluded with separate eastern and western sectional tournaments, hosted in Ann Arbor and Grand Rapids.

Early in May of 1942, MHSAA executive director Charlie Forsythe, nephew of Louis Forsythe, announced that the Association was “working on plans designed to make body-building exercises available to more young men and to spread recognition of sports achievements. He predicted substantial growth of intramural sports to include youngsters whose limited prowess might keep them from such interscholastic sports as football, baseball or basketball.”

Wire articles had told the story of how the running Battle of the Atlantic had impacted U.S. ocean transportation along the eastern seaboard. A Germany-mounted “campaign against American coastal shipping” by U-boats (submarines) was devastating “a section of America almost exclusively dependent upon ocean-point tankers for its petroleum products.” Without a viable alternative means to transport the products, on May 15, 1942, gasoline rationing began in 17 seaside states and the District of Columbia. It was hinted that gas rationing – specifically designed to save rubber – could roll out nationally. (Crude oil is the main ingredient in man-made rubber.)

The chances for restrictions in Michigan were a distinct possibility. According to P.J. Hoffmaster, the state’s supervisor of wells, the state consumed approximately 140,000 barrels of oil per day, but produced only 64,054 barrels. “This state has a shortage of at least 100,000 barrels on the basis of a regional demand,” he said, noting Michigan oil also supported needs outside the state. “When people say there can’t be rationing in Michigan because we have plenty of our own oil, they don’t have the true picture.”

Reverberations begin

When quizzed on the subject before the annual Lower Peninsula Track and Field championships, hosted at Michigan State College in May 1942, (Charlie) Forsythe, told The Associated Press he was unsure how rationing might affect the Association’s annual playoffs.

“It is too early as yet to say exactly. … We are making every effort to maintain an adequate athletic program. Certainly where common carriers (busses and trains) will make it possible to get a team to a game, that means should be used,” Forsythe said. He added that the Association was “surprised to find the number of schools competing in this year’s tournaments practically equaled last year’s entries.”

“It is too early as yet to say exactly. … We are making every effort to maintain an adequate athletic program. Certainly where common carriers (busses and trains) will make it possible to get a team to a game, that means should be used,” Forsythe said. He added that the Association was “surprised to find the number of schools competing in this year’s tournaments practically equaled last year’s entries.”

A total of 162 schools had qualified individual contestants in the track championships, about 10 percent fewer than in 1941. However, L.L. Frimodig – the assistant director of college athletics at M.S.C. and acting director of the state track meet – felt “the actual field in the four-class carnival would be much smaller than the number eligible to compete,” considering the circumstances of travel. “Many coaches,” he said, “would think in terms of tires rather than trophies before embarking on any sizable journey to the meet.”

The threat of rationing was almost immediately seen within Michigan’s resorts and travel industry.

“July and August have been moved up into June,” wrote the Detroit Free Press. “This is the word that comes from various parts of the state. Evidently, determination to get the vacation over before gas rationing may be decreed is one of the factors that has stepped up the season. … Reports of heavy patronage at nearby resorts over Memorial Day week-end can be taken as an indication of the trend, or necessity in 1942 of holidays enjoyed close to home base.”

Come September, Joseph B. Eastman, national director of the office of war transportation, called for help in reducing consumption of natural resources: “We intend to solicit the help of colleges and universities in making arrangements for transfer of scheduled games to centers of population where as many people as possible will have an opportunity to attend football games without traveling.”

At the college level, the freshman eligibility rule was waived due to the loss of manpower tied to military enlistment and the enactment of the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. Its passage required all men between ages 21 and 45 to register for the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. With entry into the war, in December 1941, it was amended to require all 18 to 64-year-olds to register, with starting age for likely draft lowered to 20.

“The seasons of 1942-45 turned the (college) game upside down, creating new juggernauts and decimating some old ones,” wrote Sports Illustrated in its 1971 article, “When Football Went to War.”

“Michigan’s 85 high school athletic leagues are speculating on the effects of the office of defense transportation plan to whittle sports travel drastically,” stated an Associated Press (AP) article soon after Eastman’s announcement. The Southwestern Conference, comprised of Kalamazoo Central, Benton Harbor, Muskegon, Holland, Grand Haven and Muskegon Heights and one of the most widely spread major prep circuits in the state, was told by its regular bus company that its busses were not available for charter.

“Michigan’s 85 high school athletic leagues are speculating on the effects of the office of defense transportation plan to whittle sports travel drastically,” stated an Associated Press (AP) article soon after Eastman’s announcement. The Southwestern Conference, comprised of Kalamazoo Central, Benton Harbor, Muskegon, Holland, Grand Haven and Muskegon Heights and one of the most widely spread major prep circuits in the state, was told by its regular bus company that its busses were not available for charter.

On Sept. 25, according to AP, “the state department of public instruction warned today that a threat of ‘no new tires’ will be held over rural schools which use their school busses to transport football players to and from games.”

Julian W. Smith, named the interim director of the MHSAA when Charlie Forsythe went into military service, didn’t think the directive would have much impact on football schedules. “However, I believe the order will have a serious effect on basketball schedules this winter and on next year’s football schedule.”

“Four Gallons a Week for Most Drivers”

Two days later it was announced that nationwide gas rationing would go into effect at the beginning of December 1942. More immediately, compulsory tire inspections every 60 days and a “Victory Speed Limit” of 35 miles per hour, effective Oct. 1, were also enacted. “This is not a gasoline rationing program, but a rubber conservation program,” said William M. Jeffers, president of the Union Pacific Railroad, which had been placed in charge of the government’s struggle to alleviate the rubber shortage.

“The object is not to take cars off the road, but to keep them on the road. … The safe life of a tire at 50 miles per hour is only half as great as it is at 30 m.p.h.”

After initial announcements of game cancellations, the impact on high school football in Michigan in 1942 appears to have been minimal. Solutions were found to most challenges. In Bessemer, the high school superintendent announced that “enough persons have volunteered their automobiles to take the Speed Boy players to Calumet” for the game, scheduled for Saturday, Oct. 3. At season’s end, Flint Northern, Detroit Catholic Central, Muskegon, and Wyandotte each lay claim to a share of Michigan’s mythical football title.

After initial announcements of game cancellations, the impact on high school football in Michigan in 1942 appears to have been minimal. Solutions were found to most challenges. In Bessemer, the high school superintendent announced that “enough persons have volunteered their automobiles to take the Speed Boy players to Calumet” for the game, scheduled for Saturday, Oct. 3. At season’s end, Flint Northern, Detroit Catholic Central, Muskegon, and Wyandotte each lay claim to a share of Michigan’s mythical football title.

But a hint of what was to follow came with an announcement concerning the annual Cross Country Finals. The state meet was cancelled to reduce travel, with honors instead awarded during October meets to which schools were assigned based on geography.

In its October 1942 bulletin, the MHSAA endorsed a commando-type “training plan drafted by the Minnesota branch of the office of civilian defense” to “step up scholastic physical fitness programs.” When plotted on a football field, the course bordered the playing area with 11 obstacles spaced 20 yards apart. The course required participants to jump a 4-foot fence, crawl under a 2-foot-high rope, then run between a maze of stakes and, later in the course, high-step through a series of open boxes. Students would scale a 7½-foot wall, walk on a 12-foot balance beam, swing across a broad jump pit from a rope that hung from above, then climb another rope hung from the crossbar of the goal posts. Once accomplished, the participant was to move, hand-over-hand, across the span of the crossbar before dropping to the ground.

At the end of October, the MHSAA’s Representative Council acknowledged the direct contribution that interscholastic sports had on the “lives of students and citizens of the communities in which they are offered” while recommending that they be “retained insofar as possible.”

The committee, however, also emphasized its belief “that physical fitness programs for all students, and intramural sports to offer opportunity for competition to all, should be stressed in the schools’ athletics program.

“In all probability,” it continued, “it will be necessary to modify the general plans of conducting tournaments.” The mechanics of modification would be hammered out at the next Council meeting to be held in December in Lansing.

Financial concerns also were expressed, as much of the Association’s operating budget came from a share of gate receipts of tournaments.

The Impact

“All over the state, athletic directors and coaches are tackling transportation problems. Instead of piling the athletes into privately owned automobiles or school busses, coaches have diligently studied timetables of regular train and bus lines with many satisfactory results,” stated the AP on Dec. 4.

That same day, the MHSAA announced that the upcoming basketball postseason would be altered due to rationing. The story was picked up by various newspapers across the Midwest.

“The association’s Representative Council last night stressed need for following a ‘principle of minimum travel’ in basketball play this winter and voted to dispense with the annual Lower Peninsula finals,” instead opting for a modified layout. Initial conversation related to a plan calling for sectional meets with the possibility of naming titles in the northern half of the Lower Peninsula, and in both the southern and eastern areas. An appointed basketball committee was also to consider combining enrollment classifications wherever necessary to localize tournament play.

From 1932-1947, inclusive, separate Lower and Upper Peninsula basketball champions were determined. The Upper Peninsula Athletic Committee announced a similar plan at its meeting in January of 1943. The committee expected to present winners of the U.P. events with certificates instead of the customary trophies due to shortage of materials prompted by the war.

According to a survey of its 40 member state associations by the National Federation of State High School Associations, Michigan was one of only four states, including Maine, Montana and Nevada, to eliminate naming basketball state champions come the winter of 1943, “since the distances within those states are too vast or transportation facilities are too limited. The same will prevail in track contests.”

By mid-January, the MHSAA had polled its membership, and approximately 95 percent of the state’s high schools indicated a desire to participate in the replacement tournaments pitched by the Association. After examining the logistics, the plan previously discussed was modified. The Association then identified 51 Lower and 11 Upper Peninsula sites, based on availability to host the tournament and geographic suitability. The competition would run for two weeks, and end with what had previously equaled District championship contests.

By mid-January, the MHSAA had polled its membership, and approximately 95 percent of the state’s high schools indicated a desire to participate in the replacement tournaments pitched by the Association. After examining the logistics, the plan previously discussed was modified. The Association then identified 51 Lower and 11 Upper Peninsula sites, based on availability to host the tournament and geographic suitability. The competition would run for two weeks, and end with what had previously equaled District championship contests.

In the meantime, the annual swim championships were reduced to a one-day meet. Hosted at the University of Michigan, the meet would tax the endurance of individual swimmers, “since officials … decided to conduct semi-final events additional to the customary qualifying trials and finals.” That meant a swimmer entered in two events could compete six times during the day, with qualifying events in the morning, semifinals in the afternoon and finals swum at night. Perennial powers Battle Creek Central and Ann Arbor University High emerged as champions.

“The war to date has proved one thing conclusively – athletics in all schools must go on, for they serve to properly condition our young men for the bigger task ahead,” said MHSAA interim director Smith, speaking at an “annual football and basketball ‘bust’ for Lakeview High School” in Battle Creek in February 1943. Smith had served as principal at the high school for 14 years before taking over at the MHSAA. He “expressed regret” that the MHSAA had altered the various formats of the annual championships. According to coverage of the gathering in the Battle Creek Enquirer, “he intimated that it, along with all other forms of statewide competition, would be restored before another school year begins.”

Continued Chaos

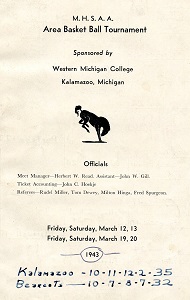

The cities of Lansing and Kalamazoo played host to the most contingents, with 25 teams across the four enrollment classifications playing games at recently completed Lansing Sexton – the rechristened Lansing Central High School – and the Lansing Boys Vocational School. A total of 23 schools squared off at Western Michigan College of Education (now Western Michigan University).

As previously stated, transportation considerations meant some schools played above or below their normal classification to make things work. Ecorse, normally a Class B school, battled in the Class A tournament hosted at Dearborn Fordson. Benton Harbor, with Class A enrollment numbers, competed in the Class B tournament played across the St. Joseph River at St. Joseph High School instead of at the Kalamazoo Area tournament against similarly-sized schools.

A total of 128 area titles were awarded across the state’s two peninsulas. Decatur, the Class C state champion in 1942 with a 25-0 record, was the only team titlist to repeat in 1943, emerging with one of the “Area” crowns and extending its streak of victories to 41 consecutive. Also among the winners was Grand Rapids Union, a “cellar team in the regular season.”

“Although Union stood seventh in the city tally, the Red Hawks won the Area Tournament Crown in three smashing, spine-tingling battles,” stated the sports editor in the 1943 Aurora - Union’s yearbook. “In fast games the Hawks overcame Catholic and beat the Creston Bears … as well as whipping Davis Tech for their final victory.”

In April, the MHSAA confirmed that competition would end with area, city or conference meets in track, and again in tennis and golf, because of transportation, participation issues, and the “prospects of closing of some of the schools early.”

Various fans and media members grumbled about the unsatisfying conclusion to the prep sports calendars.

Hope

The coaching ranks were heavily hit by the war, as numerous mentors were tapped by the armed forces to lead physical fitness programs. Despite initial concerns, few “of the state’s 400 football-playing prep schools” dropped the sport come the 1943-44 school year. As it would turn out, because of the travel constraints, attendance increased as more and more sports fans turned to high school competition for entertainment.

Smith stated in October that he had “yet to find anyone who is definitely against bringing the (basketball) championship tournament back to life. There seems to be overwhelming sentiment in favor of the revival. The schools right-about face on the state cage classic which annually drew 700 prep teams and 11,000 players is explained by the fact coaches now feel the federal government is strongly in favor of any attempt to encourage or extend athletics. Last year schoolmen were not certain what the government’s attitude on sports would be and were hesitant about continuing athletics in pre-war style.”

Only 258 of 614 schools replied to a questionnaire about restoring the winter basketball state championships, but 73 percent of respondents were in favor of such, and in December, the Representative Council voted to resume the final rounds of the tournaments.

Only 258 of 614 schools replied to a questionnaire about restoring the winter basketball state championships, but 73 percent of respondents were in favor of such, and in December, the Representative Council voted to resume the final rounds of the tournaments.

Born October 1918 in St. Johns, Michigan at the peak of the “Spanish Flu” pandemic, Hal Schram was a 25-year-old sports reporter for the Lansing State Journal when he covered the restart.

“State championship basketball and track competition once more became a part of (the) Michigan high school athletic program when the Representative Council of the MHSAA voted to reinstate these two state-wide tournaments after a suspension of one year,” he wrote.

According to Schram, “It was believed that student working hours, transportation, scarcity of balls and general lack of interest” still necessitated cancellation of golf and tennis tournaments for the year. Conduction of a swimming championship was left “in the hands of a committee representing schools which sponsor the sport … subject to the approval of the representative committee.”

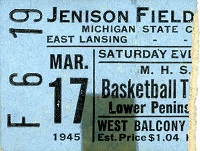

Plans were to return the final rounds of the basketball tournament to Jenison Field House on the campus of Michigan State, which had hosted those rounds from 1940-42. However, the facility was in use by Army trainees for a physical fitness program.

“We would like to have the finals staged here very much,” said MSC athletic director Ralph Young, “but our obligations to the army come first.”

“Despite the hitch, the executive committee opted to stay in Lansing, playing Class A and C semifinal contests at the Boys Vocational School fieldhouse, and Class B and D semi games at Sexton High School. Finals were held at the Vocational gym.

“Fifty-five hundred spectators jammed their way into every nook and cranny of the Boys Vocational school fieldhouse last night to see four high school teams (Saginaw Arthur Hill, Marshall, Lansing St. Mary, Benton Harbor St. John) win championships in the Lower Peninsula tournament finals. With all seats taken almost before the first game started, the big floor was completely encircled by people sitting and standing before the finish,” wrote State Journal sports editor George S. Alderton. “By 6 o’clock, when the Class D game started, all seats in the side bleachers had been filled and most of the end bleachers were gone. The last vacancy was occupied before the Class C game started at 7:15 o’clock and from that time on, those who came either stood or seized a seat left by some departing fan. In many instances two sat down when one departed. Corners of the court were seething masses of humanity …”

United Press International wire reports indicated that 8,500 in total saw the Finals, as fans shifted in and out of the venue in support of the participating teams. “Some people had to be turned away at the finals,” said Smith, “and that certainly shows that people need and want this kind of relaxation.” The previous three Finals at MSC had drawn between 6,000-7,000 fans, while the 1939 Finals at I.M.A in Flint drew 5,000 and the 1938 event at Grand Rapids Civic Auditorium saw 6,000 attend.

“Lighting was so poor in the press box Friday night for the semi-finals,” added Alderton, “that workers came equipped with candles for the finals on Saturday night and propped them against their typewriters.”

Ishpeming hosted the Upper Peninsula Finals, as Escanaba, Crystal Falls, Channing and Amasa swept titles, respectively, in Classes B, C, D and Class E – the state’s smallest classification, reserved only for the smallest U.P. schools based on enrollment.

“Only complaint,” noted the Marquette Mining Journal, “was from those who couldn’t get in or were caught in a jam of fans seeking general admission seats. … Probably another 100 to 200 could have been accommodated if they were permitted to sit on the floor all along the court lines, but this would have been hazardous to players and fans …”

(The Lower Peninsula finals returned to Jenison in 1945 – where they stayed, uninterrupted, through 1970 – and were played before 7,833 spectators that first season back. Locals were delighted as they watched Lansing Sexton top Benton Harbor’s undefeated Tigers, 31-30. Michigan Governor Harry Kelly “personally presented the Class B championship trophy to Sturgis Capt. Tom Tobar, congratulated Capt. Larry Thomson of East Lansing and then shook hands with the captains of the Class A contest before the game started.”)

(The Lower Peninsula finals returned to Jenison in 1945 – where they stayed, uninterrupted, through 1970 – and were played before 7,833 spectators that first season back. Locals were delighted as they watched Lansing Sexton top Benton Harbor’s undefeated Tigers, 31-30. Michigan Governor Harry Kelly “personally presented the Class B championship trophy to Sturgis Capt. Tom Tobar, congratulated Capt. Larry Thomson of East Lansing and then shook hands with the captains of the Class A contest before the game started.”)

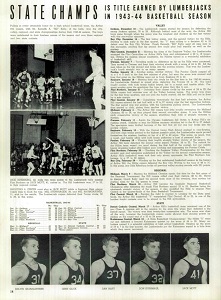

In mid-May, “some 800 Michigan prep trackmen, survivors of 40 regionals at 10 centers” headed to Michigan State College to determine statewide champs. Only Kalamazoo in Class A and Birmingham in Class B held the chance to “repeat” as team champions. Instead, Saginaw Arthur Hill capped a stellar sports year, earning its first Class A team track title to go with its recently-earned basketball crown. (Earlier in the school year, the Lumberjacks also had opened their own football field.)

East Grand Rapids earned its second track title, grabbing the Class B crown. Fowlerville and Glen Arbor Leelanau brought home titles in Class C and D, respectively.

All sports – including golf and tennis which had gone three years without competing in a true state title round – returned to their original formats with the start of the 1944-45 school year.

In May 1945, Germany surrendered to the Allies, followed by Imperial Japan’s surrender, announced in August.

Participation in prep sports and attendance numbers would explode across the state and the nation in the coming years, tied to multiple factors, including, of course, the baby boom that followed World War II.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) Grand Rapids Union was among "Area" boys basketball champions in 1943. (2) Lewis Forsythe, left, and Charles Forsythe were among leaders during the MHSAA's first decades (3) The Saginaw Arthur Hill yearbook for 1944 tells of fitness training undertaken by students. (4) Julian W. Smith served as interim MHSAA executive director while Charles Forsythe was serving in the military. (5) Flint Northern's Bill Hamilton earned all-state honors in 1942. (6) Western Michigan College was among hosts of 1943 Area tournaments. (7) Arthur Hill's yearbook celebrates the 1943-44 boys basketball championship. (8) Basketball Finals returned to Jenison Field House in 1945. (9) The MHSAA paid tribute to World War II veterans in its 1945 Basketball Finals program.

Breslin Bound: 2022-23 Boys Semifinals Preview

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

March 22, 2023

For several reasons, crossing over all four divisions, this weekend’s MHSAA Boys Basketball Semifinal & Finals could be among the most memorable we’ve played in some time.

The longtime powers will be back at Breslin Center. Six teams with at least three Finals championships will be looking to add to those totals. At the same time, eight teams will be playing for their first title – and a ninth may be playing for the last of its storied history.

There will be favorites. In Division 1 alone, all four semifinalists finished the regular season among the top nine in Michigan Power Rating. But numbers have a tough time anticipating an unpredictable story, and we have plenty – in Divisions 2, 3 and 4 only half the remaining contenders finished among the top 20 in MPR in their respective rankings.

DIVISION 1 - Friday

Detroit Cass Tech vs Grand Blanc - Noon

Orchard Lake St Mary's vs Muskegon - 2 p.m.

DIVISION 2 - Friday

Saginaw vs Ferndale - 5:30 p.m.

Grand Rapids South Christian vs Romulus Summit Academy North - 7:30 p.m.

DIVISION 3 - Thursday

Flint Beecher vs Ecorse - Noon

Traverse City St Francis vs Niles Brandywine - 2 p.m.

DIVISION 4 - Thursday

Munising vs Marine City Cardinal Mooney - 5:30 p.m.

Frankfort vs Wyoming Tri-unity Christian - 7:30 p.m.

Finals - Saturday

Division 1 - 12:15 p.m.

Division 2 - 6:45 p.m.

Division 3 - 4:30 p.m.

Division 4 - 10 a.m.

Tickets for this weekend’s games are $12 for both Semifinals and Finals and available via the Breslin Center ticket office; for information and links visit the Boys Basketball page.

All Semifinals will be broadcast and viewable with subscription on MHSAA.tv, and all four Finals will air live Saturday on Bally Sports Detroit – Divisions 4, 3 and 2 on the primary channel and Division 1 on BSD Extra – as well as on the BSD website and app. Audio broadcasts of all Semifinals and Finals will be available free of charge from the MHSAA Network.

The Boys Basketball Semifinals & Finals are sponsored by Sparrow Health System.

Here’s a look at the 16 semifinalists (with rankings by MPR and statistics through Regional Finals unless noted):

Division 1

DETROIT CASS TECH

Record/rank: 26-1, No. 4

League finish: First in Detroit Public School League Blue and overall

Coach: Steven Hall, seventh season (149-30)

Championship history: Class A runner-up 1974.

Best wins: 55-49 over No. 10 Ann Arbor Huron in Quarterfinal, 71-59 (District Semifinal), 74-70 (OT) and 57-55 over Detroit Martin Luther King, 59-42 over No. 15 Grand Rapids Northview, 69-63 over Division 3 No. 3 Flint Beecher, 46-39 over Division 3 No. 8. Traverse City St. Francis.

Players to watch: Darius Acuff, 6-2 soph. G (21.6 ppg, 5.8 apg); Kenneth Robertson, 6-0 sr. F (15.3 ppg, 5.0 rpg); Travon Cooper, 6-5 sr. C/F (11.5 ppg, 8.9 rpg, 2.9 bpg).

Outlook: After falling just two points shy in a Quarterfinal last season, Cass Tech is returning to the Semifinals for the first time since 1993 and only a one-point overtime loss to Bloomfield Hills Brother Rice from a perfect run this season. Hall led Detroit Rogers to three straight Class D titles from 2003-05 and returned to his alma mater Cass Tech in 2015-16 after serving as a college assistant at Duquesne and Youngstown State. Acuff earned an all-state honorable mention as a freshman and is one of the top sophomores in the state, and he’s got lots of help – after Robertson and Cooper as well, four more players average at least six points per game.

GRAND BLANC

Record/rank: 25-2, No. 3

League finish: First in Saginaw Valley League

Coach: Tory Jackson, first season (25-2)

Championship history: Division 1 champion 2021, two runner-up finishes.

Best wins: 70-62 (OT) over No. 5 Muskegon, 60-49 over No. 9 Orchard Lake St. Mary’s, 42-31 over No. 11 Warren De La Salle Collegiate, 74-46 over Division 2 No. 5 Cadillac, 57-43 over Division 3 No. 3 Flint Beecher.

Players to watch: Tae Boyd, 6-3 sr. F (15.4 ppg); RJ Taylor, 6-0 sr. G (14.3 ppg, 6.0 rpg, 6.2 apg); Bryce O’Mara, 6-7 jr. F (8.3 ppg, 5.3 rpg).

Outlook: Grand Blanc has played in the last two Division 1 championship games, finishing runner-up to De La Salle last season. Three starters plus the top two subs from last year’s Final are back – and that’s with another returning starter, Nathan Richardson, out since February with an injury. Taylor made the all-state first team last season and will continue at Northern Iowa, and Boyd earned an all-state honorable mention in 2022 and intends to play basketball and football at Ferris State. Jackson was part of two Class C championships as a player at Saginaw Buena Vista and played at Notre Dame and in the NBA G-League before getting his start in coaching at Buena Vista in 2012-13.

MUSKEGON

Record/rank: 25-2, No. 5

League finish: First in Ottawa-Kent Conference Green

Coach: Keith Guy, 11th season (229-36)

Championship history: Three MHSAA titles (most recent 2014), two runner-up finishes.

Best wins: 68-48 over East Kentwood in Regional Semifinal, 67-60 over No. 8 Kalamazoo Central, 50-45 over Division 2 No. 6 Warren Lincoln, 62-51 over Division 2 No. 1 Ferndale, 81-79 (OT) over Division 2 No. 19 Grand Rapids Catholic Central.

Players to watch: Jordan Briggs, 6-1 sr. G (18.7 ppg, 84 3-pointers, 5.1 rpg, 6.0 apg); Anthony Sydnor III, 6-2 sr. G (14.3 ppg, 5.6 rpg, 5.6 spg); David Day III, 5-9 sr. G (8.1 ppg, 4.3 apg).

Outlook: Muskegon has won 20 or more games nine of the last 10 seasons despite annually loading the schedule with elite opponents. Briggs, Sydnor and Day are the only three seniors and set the pace as the team’s top three scorers and 3-point shooters. Briggs made the all-state first team last season and signed with Wayne State, and Sydnor earned an all-state honorable mention and signed with Ferris State. They are surrounded by several teammates contributing big in their roles, including 6-6 junior Terrance Davis (6.8 ppg, 9.6 rpg) and 6-5 junior Stanley Cunningham (7.6 rpg) in the frontcourt and junior guard M’Khi Guy (5.0 apg) off the bench.

ORCHARD LAKE ST. MARY’S

Record/rank: 16-10, No. 9

League finish: Tied for fourth in Detroit Catholic League Central

Coach: Todd Covert, eighth season (127-52)

Championship history: Four MHSAA titles (most recent 2000), two runner-up finishes.

Best wins: 55-44 (Quarterfinal) and 63-45 over No. 11 Warren De La Salle Collegiate, 56-44 over No. 2 North Farmington in Regional Final, 72-69 (Regional Semifinal) and 67-64 over No. 6 Detroit U-D Jesuit, 57-50 over No. 1 Bloomfield Hills Brother Rice in District Final, 56-41 over East Kentwood, 68-64 (3OT) over Division 2 No. 6 Warren Lincoln, 67-51 over Division 2 No. 19 Grand Rapids Catholic Central, 54-39 over Division 2 No. 1 Ferndale.

Players to watch: Trey McKenney, 6-5 soph. G/F (25.5 ppg, 11.1 rpg); Sharod Barnes, 6-2 soph. G (10 ppg); Daniel Smythe, 6-3 jr. G (10 ppg).

Outlook: St. Mary’s rumbled through one of the state’s toughest schedules during the regular season, and it’s certainly paid off during a postseason run that’s been perhaps the most impressive regardless of division. The Eaglets had reached the Quarterfinals the last two years and will make their first Semifinal appearance since 2006. McKenney made the all-state second team last season and is already considered among the state’s best as well as just a sophomore. Juniors Andrew Smith and Mason Wisniewski round out the starting lineup, both averaging just over six points per game and the 6-6 Wisniewski also grabbing 7.4 rebounds per contest.

Division 2

FERNDALE

Record/rank: 19-8, No. 1

League finish: Second in Oakland Activities Association Red

Coach: Juan Rickman, fifth season (87-32)

Championship history: Two MHSAA titles (most recent 1966).

Best wins: 69-50 over No. 16 Warren Michigan Collegiate in Regional Final, 64-47 and 60-52 over Division 1 No. 20 Oak Park, 82-65 over Division 1 No. 12 Port Huron Northern, 72-60 over Division 1 No. 7 River Rouge, 67-61 over Division 1 No. 13 Grosse Pointe South, 63-52 over Division 3 No. 3 Flint Beecher.

Players to watch: Christopher Williams, 6-5 sr. G/F (13.5 ppg, 10.1 rpg); Cameron Reed, 6-0 sr. G (10.1 ppg, 7.5 apg); Noah Blocker, 6-1 sr. G (12.8 ppg).

Outlook: Ferndale is another contender that navigated a difficult regular-season schedule but is up to 14 wins over its last 15 games as it makes a third-straight trip to the Semifinals. All five starters are seniors, and Williams, Reed and Blocker all started in last year’s Semifinal as well, plus seniors Caleb Renfroe and Jacoby Jackson were the most-played subs in that game. Senior Jayden Hardiman adds another 9.2 points and 8.9 rebounds per game and provides a 6-7 presence in the middle. Junior Trenton Ruth (8.1 ppg) is among the top options off the bench this season.

GRAND RAPIDS SOUTH CHRISTIAN

Record/rank: 24-3, No. 12

League finish: Tied for first in O-K Gold

Coach: Taylor Johnson, first season (24-3)

Championship history: Three MHSAA titles (most recent 2005), two runner-up finishes.

Best wins: 82-54 over No. 19 Grand Rapids Catholic Central, 61-38 (Quarterfinal) and 58-50 over Hudsonville Unity Christian, 64-48 over East Kentwood, 58-36 over Division 3 No. 14 Detroit Edison.

Players to watch: Jake Vermaas, 6-1 jr. G (12.6 ppg, 6.5 rpg, 4.5 apg); Jacob DeHaan, 6-2 sr. G (13 ppg, 5.5 rpg); Sam Medendorp, 6-6 sr. F/C (8.9 ppg, 6.2 rpg, 1.8 bpg).

Outlook: South Christian has upped its winning streak to 15 straight since losing its first meeting with GRCC on Jan. 24, and all 15 of those wins have come by double digits. Johnson came to South Christian this season after six as an assistant coach at Grand Valley State and has the Sailors in their first Semifinal since 2005. They did lose leading scorer Carson Vis (17.7 ppg) with a season-ending injury in the Regional Final, but DeHaan responded with a team-leading 27 points in the Quarterfinal win. DeHaan earned an all-state honorable mention last season.

ROMULUS SUMMIT ACADEMY

Record/rank: 25-2, No. 22

League finish: First in Charter School Conference West

Coach: Mark White, fifth season (91-22)

Championship history: Has never appeared in an MHSAA Final.

Best wins: 68-62 over Chelsea in Quarterfinal, 57-27 over Flat Rock in District Final, 74-43 over Brownstown Woodhaven, 73-60 over Division 3 No. 14 Detroit Edison.

Players to watch: James Wright, 6-4 sr.; Dontez Scott Jr., 6-0 jr. G; Amir Perryman, 5-10 soph. G. (Statistics not submitted.)

Outlook: White, who led Detroit Renaissance to Class B championships in 2004 and 2006, has Summit in its first Semifinal after guiding the Dragons to their first Quarterfinal in 2021. Their only losses this season were to teams that finished a combined 46-5 – Warren Michigan Collegiate and Detroit Loyola. Wright made the all-state second team last season, and Scott earned an honorable mention.

SAGINAW

Record/rank: 21-6, No. 32

League finish: Sixth in SVL

Coach: Julian Taylor, 12th season (203-75)

Championship history: Six MHSAA titles (most recent 2012).

Best wins: 61-57 over No. 5 Cadillac in Quarterfinal, 78-58 over Flint Hamady in Regional Final, 47-33 over Shepherd in Regional Semifinal, 74-38 over Carrollton in District Final.

Players to watch: Javarie Holliday, 6-2 sr. G (15.8 ppg); DaRon Sherman, 6-2 sr. G (10 ppg, 8.0 apg, 3.9 spg); Taelor Lowery, 6-0 sr. G (11 ppg).

Outlook: This will be Saginaw’s first trip to the Semifinals since 2013, and potentially carries even more historical significance with the school set to merge with Arthur Hill for the start of the 2024-25 school year. Playing in the predominantly Division 1 SVL, Saginaw’s losses all were to D1 opponents. Four of five starters are seniors, and 6-3 senior forward D’Quan Lowe Patman adds 6.3 points, 10.3 rebounds and three steals per game. Holliday earned an all-state honorable mention last season.

Division 3

ECORSE

Record/rank: 20-4, No. 34

League finish: Tied for second in Michigan Metro Athletic Conference Black

Coach: Gerrod Abram, fourth season (59-25)

Championship history: Class B runner-up 1978, Class B Lower Peninsula runner-up 1942.

Best wins: 57-46 over No. 5 Laingsburg in Quarterfinal, 69-58 over Plymouth Christian Academy in Regional Final, 63-46 over No. 19 Riverview Gabriel Richard in Regional Semifinal, 85-69 over Brownstown Woodhaven.

Players to watch: Malik Olafioye, 6-3 sr. PG; Kenneth Morrast Jr., 6-1 sr. PG; Dennell Kemp Jr., 6-0 jr. G. (Statistics not submitted.)

Outlook: After reaching the Semifinals last season for the first time since 1980, Ecorse is making a second-straight trip. Olafioye, Morrast and Kemp all started in last season’s Semifinal, and Olafioye made the all-state first team while Morrast earned an honorable mention. The losses this season came to Division 1 Oak Park, Detroit Renaissance and Detroit Catholic Central – all in December – and Division 2 Detroit University Prep on Feb. 17 after having defeated the Panthers three weeks earlier.

FLINT BEECHER

Record/rank: 22-4, No. 3

League finish: First in Genesee Area Conference Red

Coach: Marquis Gray, second season (44-7)

Championship history: Nine MHSAA titles (most recent 2021), four runner-up finishes.

Best wins: 55-49 over No. 1 Detroit Loyola in Quarterfinal, 65-41 over No. 7 Saginaw Nouvel in Regional Final, 57-33 over No. 9 Cass City in Regional Semifinal, 70-55 over Goodrich, 48-43 and 80-71 over Flint Hamady.

Players to watch: Kevin Tiggs Jr., 6-2 sr. F (14 ppg, 5.4 rpg); Keyonta Menifield, 5-10 jr. G (8.5 ppg); Robert Lee Jr., 6-2 sr. F/G (24.1 ppg, 6.5 rpg, 4.2 apg).

Outlook: Beecher is making its third-straight Semifinals appearance and bringing back two starters and the top two subs from the lineup that played at Breslin a year ago. Lee made the all-state first team last season and can erupt at any time making more than 50 percent of his shots from the floor total and 3-point range as well. Tiggs is making more than 60 percent of his shots from the floor and also has put up big numbers. Beecher once again loaded up its regular-season schedule; the Bucs’ losses were to Division 1 Grand Blanc and Cass Tech – both playing this weekend – and Division 2 Ferndale (also still playing) and Benton Harbor.

NILES BRANDYWINE

Record/rank: 25-2, No. 28

League finish: Second in Lakeland Conference

Coach: Nathan Knapp, 18th season (212-170)

Championship history: Has never appeared in an MHSAA Final.

Best wins: 71-62 over Pewamo-Westphalia in Quarterfinal, 58-42 over Kalamazoo Hackett Catholic Prep in Regional Semifinal, 42-36 over No. 6 Watervliet in District Final, 61-35 over Cassopolis.

Players to watch: Jamier Palmer, 6-0 jr. G (10.1 ppg, 5.0 rpg, 4.0 apg); Jaremiah Palmer, 6-0 jr. G (12.9 ppg); Byron Linley, 6-1 jr. G (9.7 ppg).

Outlook: Brandywine is making its first trip to the Semifinals after also winning its first Regional title, and Knapp has led an incredible transformation of the program. After not posting a winning record until his seventh season, Brandywine has reached 18 wins five of the last eight seasons with six league and three District titles during that time as well. The only losses this season were to Division 2 Benton Harbor, and 19 wins have come by double-digit margins. There’s only one senior in the eight-player regular rotation, and freshman guard Nylen Goins also averages 9.7 ppg and had a team-high 43 3-pointers entering the week.

TRAVERSE CITY ST. FRANCIS

Record/rank: 23-4, No. 8

League finish: Tied for first in Lake Michigan Conference

Coach: Sean Finnegan, sixth season (106-26)

Championship history: Class C runner-up 2012.

Best wins: 46-37 (Regional Final) and 61-49 over No. 18 McBain, 58-22 and 60-42 over No. 16 Elk Rapids, 58-34 over Division 2 No. 11 Boyne City, 63-54 over Canton.

Players to watch: Wyatt Nausadis, 6-4 sr. G (20.1 ppg, 40 3-pointers, 3.0 apg); Joey Donahue, 6-3 sr. F (7.8 ppg, 3.1 apg); John Hagelstein, 6-0 soph. G (10.1 ppg, 6.9 rpg). (Statistics through end of regular season.)

Outlook: St. Francis has been building toward this first Semifinal since 2012, improving from 12 wins two seasons ago to 19 last winter and now this run. They bounced back from a six-point loss to Boyne City on Jan. 24 for a 24-point win Feb. 21 to share the league title, and playoff wins over Maple City Glen Lake (19 wins) and St. Ignace (22) also were among the most noteworthy. Nausadis made the all-state second team last season, and 6-5 senior Drew Breimayer (7.7 ppg) is among more contributors who can pick up scoring load.

Division 4

FRANKFORT

Record/rank: 18-8, No. 57

League finish: Fourth in Northwest Conference

Coach: Dan Loney, fifth season (86-41)

Championship history: Division 4 runner-up 2019.

Best wins: 59-57 over Hillman in Quarterfinal, 50-44 over No. 7 Lake Leelanau St. Mary in Regional Final, 52-47 over No. 12 Gaylord St. Mary in Regional Semifinal, 60-51 over Maple City Glen Lake.

Players to watch: Emmerson Farmer, 5-10 sr. G (10.7 ppg, 37 3-pointers); Nick Stevenson, 6-2 sr. F (9.0 ppg, 9.9 rpg); Carter Kerby, 5-10 soph. G (11 ppg, 3.0 apg).

Outlook: Frankfort found its stride at the right time with nine wins over its last 10 games and the Glen Lake and Lake Leelanau St. Mary victories avenging earlier losses. It didn’t come easily, as all five of the Panthers’ playoff opponents finished the regular season with winning records. Frankfort had made the Quarterfinals as recently as 2021, but fell back to 11-12 last season before bouncing back big this winter. A balanced lineup gets contributions from several players; senior Xander Sauer is another, averaging 10.2 points per game.

MARINE CITY CARDINAL MOONEY

Record/rank: 16-11, No. 49

League finish: Tied for fifth in Detroit Catholic League Intersectional #1

Coach: Mike McAndrews, 25th season (303-207)

Championship history: Class D runner-up 2010.

Best wins: 59-56 over No. 9 Taylor Trillium Academy in Quarterfinal, 57-44 over No. 6 Genesee Christian in Regional Final, 75-65 over Plymouth Christian Academy, 52-46 over Kalamazoo Hackett Catholic Prep.

Players to watch: Brian Everhart, 6-0 jr. G (12.3 ppg); Dominic Cattivera, 6-5 sr. C (10.4 ppg, 7.0 rpg); Trent Rice, 6-0 sr. G (12.9 ppg).

Outlook: This run might seem a little unexpected as well, especially given the teams Cardinal Mooney has defeated the last two rounds. But the Cardinals have won nine of their last 12 after working through a league that included only one other Division 4 team along with two from Division 2 and two from Division 3. All but one loss came to an opponent from D1, D2 or D3, including a pair to Loyola and another to Division 1 De La Salle. Rice earned an all-state honorable mention last season and is one of our senior starters. Quentin Hillaker is another, averaging 9.1 points and 5.3 rebounds per game.

MUNISING

Record/rank: 25-1, No. 2

League finish: First in Skyline Central Conference – Large

Coach: Terry Kienitz, seventh season (128-22)

Championship history: Has never appeared in an MHSAA Final.

Best wins: 52-43 over No. 1 Painesdale Jeffers in Quarterfinal, 60-28 over No. 11 Mackinaw City in Regional Final, 61-50 (Regional Semifinal) and 67-64 over No. 17 Rudyard, 70-65 over No. 18 Norway, 62-59 and 54-49 over No. 3 Powers North Central.

Players to watch: Kane Nebel, 6-2 sr. G (15.8 ppg, 6.1 rpg, 6.8 apg, 4.5 spg); Trevor Nolan, 5-8 soph. G (15 ppg, 54 3-pointers); Jack Dusseault, 6-3 soph. C (10.9 ppg, 7.4 rpg). (Statistics through end of regular season.)

Outlook: Munising emerged from a powerful group of Upper Peninsula teams in Division 4, and that on its own says a ton about its chances this weekend. This also will be the program’s first Semifinal since 1954. The Mustangs have won 14 straight games since losing a four-pointer to Brimley on Jan. 17, and this run came after last year’s ended with the team 19-3 and the 2020-21 team finished 15-2. Carson Kienitz is a third sophomore starter and provides more size at 6-3 and scoring at 11.4 ppg along with 5.4 rpg.

WYOMING TRI-UNITY CHRISTIAN

Record/rank: 21-6, No. 15

League finish: Tied for second in Alliance League

Coach: Mark Keeler, 36th season (669-210)

Championship history: Five MHSAA titles (most recent 2022), five runner-up finishes.

Best wins: 54-41 over No. 5 Kalamazoo Phoenix in Quarterfinal, 62-44 over Lansing Christian in Regional Final, 79-36 over No. 13 Baldwin in Regional Semifinal, 57-52 over Pewamo-Westphalia, 51-46 over Schoolcraft.

Players to watch: Jordan VanKlompenberg, 6-1 jr. G (10.8 ppg, 59 3-pointers, 3.5 apg); Roy Fogg, 6-3 sr. G/F (13 ppg); Owen Rosendall, 6-0 jr. G (7.1 ppg, 36 3-pointers).

Outlook: Tri-unity is the reigning champion and also was the Division 4 runner-up in 2021. VanKlompenberg and Rosendall started last season, and Rosendall also was a top sub as a freshman. The Defenders have won 10 of their last 11 games this winter and all five playoff matchups by at least 13 points, and all six losses came to opponents from Divisions 1-3. Sophomore Keaton Blanker adds 7.8 ppg, and junior Akais Giplaye (6.2 ppg, 6.8 rpg) also has moved into the starting lineup after seeing 12 minutes off the bench in last year’s championship game.

PHOTOS (Top) Flint Beecher’s Damarcus Burke Jr. (13) drives with Grand Blanc’s Trevon Johnson defending during their regular-season finale matchup. (Middle) Munising's Kane Nebel (0) works to get past Jeffers' Ashton Kunishige (13) and Levi Frahm (3) during a Tuesday Quarterfinal. (Top photo by Terry Lyons; middle photo by Cara Kamps.)