Hayes Jones: Olympic Hero Built in Pontiac

April 30, 2019

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

His mother was going to name him Kelly, chosen to honor her brother who had passed away. But before the birth certificate would be filed at the county seat for Ethel’s newborn son, there was a change of plan.

He was born in August of 1938 in Starkville, Mississippi, into a world at unrest. Not yet officially at war, it would be soon.

Ethel’s father had a different suggestion. His daughter had another brother, who served in the Navy. If something were to happen to her brother, there would be no one else to carry on the family surname. With that, it was decided.

Instead, the child’s first name would be Hayes.

At the age of 80, Hayes Jones is happy to share the details of his life. Especially when the conversation offers the occasion to remember the people and places that most impacted his being. The conversation, as it always has, includes stories about mentors. These are the people who he will never forget.

The names and the stories are certainly not new. Many have appeared, in some form, in newspaper interviews from five, 15, 50, or 60 years ago. They are told with joy and admiration.

He speaks in measured tones, at a moderate and deliberate pace.

"I grew up a kid with a nervous condition, bad ulcers in junior high and I stammered," he told Marvin Goodwin of the Oakland Press in 2014. "I couldn't speak a sentence without stuttering."

“I still have that, if I get overly excited,” said Jones, speaking on his cell phone while on a recent visit to metro Detroit.

For the past 10 years, Jones has lived in Atlanta, Ga., and spends most of his time there. But he lived in and around Pontiac for years while working in and near the Motor City. He still has a home there and returns to visit with family.

Academics nearly derailed what was to come, but with a willingness to listen, absorb, then act, he would become a state track champion. At the age of 22, he held three world records and was an Olympic medalist. By 26, he would earn gold.

The spring of '55

Jones’ name first surfaced before a statewide audience in early April 1955 in a stringer’s report to the Detroit Free Press.

“Pontiac completely outclassed 11 other Class A foes here Friday night to win its first Arthur Hill-Saginaw High School invitational indoor track title at Central Michigan College’s fieldhouse. … Coach Wally Schloerke’s balanced outfit won six of the first 10 events.

“Leading the way for Pontiac was Willie Wilson who captured the high and low hurdles. Other Pontiac winners were Hayes Jones in the broad jump and Morris Jackson in the 440. The Chiefs also won both the medley and four-lap relays.”

“The final score of the winners more than doubled the points of runner-up, Flint Northern, who tallied 30½ points to the winner’s 69½ points,” stated the Traverse City Record Eagle in its extensive coverage of the event. Jones, a junior, had also tied for first, with teammate Hudson Ray, in the high jump, finished second in the 65-yard low hurdles and fourth in the high hurdles.

Two weeks later in the Free Press, sportswriter Hal Schram noted that Pontiac had won its second straight dual meet, overwhelming Dearborn Fordson, 84 1/3 to 24 2/3. “Hayes Jones won two events outright and tied for a third in piling up 14 points. He won the high hurdles in 15.4 seconds, the broad jump at 19 feet 2 inches and tied in the high jump at 5 feet 11 inches.” According to Schram, the Chiefs were already being “touted as the team to beat for Class A track honors.”

Competing in the ultra-competitive Saginaw Valley Conference, track success was relatively new to PHS. With the assistance of Ray Lowry, who previously served as Pontiac’s track coach, Schloerke’s Chiefs had finished as runners-up to the Class A state title in the springs of 1952 and 1953.

In the Regional at Ypsilanti, Pontiac qualified 19 athletes over 11 of the meet’s 13 events. Jones won the high hurdles and broad jump.

“Herb Korf, veteran coach at Saginaw High whose teams won seven (track) State titles in 10 years (1945-1954) admits he never had a squad with the depth and balance of this Pontiac powerhouse,” wrote Schram in his preview of the 1955 state meet. “The Chiefs won’t win many first places Saturday but will pile up the seconds, thirds and fourths. Willie Wilson and Hayes Jones in the hurdles and Freeman Watkins in the broad jump have the best chances of winning events.

“’It appears to be a battle for second place,’ is the begrudging forecast of Bill Cave, Flint Northern coach. who dislikes playing second fiddle to anyone.” (Cave and Flint Northern won MHSAA Class A titles in 1950 and 1953 and then ended 1954 second to Saginaw. The Vikings would then finish as Class A runners-up in each of the next six years before earning another title in 1961.)

“’It appears to be a battle for second place,’ is the begrudging forecast of Bill Cave, Flint Northern coach. who dislikes playing second fiddle to anyone.” (Cave and Flint Northern won MHSAA Class A titles in 1950 and 1953 and then ended 1954 second to Saginaw. The Vikings would then finish as Class A runners-up in each of the next six years before earning another title in 1961.)

As predicted, Pontiac grabbed an easy victory at the Class A meet, hosted at Michigan State’s Ralph Young Field. The Chiefs scored 51 13/14 points to Flint Northern’s 17. Jones alone racked up 17 points, winning the 120-yard high hurdles with a record time of 14.5 seconds, shaving a tenth of a second off the mark held for 14 years by Jackson’s Horace Smith. Jones also won the broad jump and finished second to Benton Harbor’s Don Arend in the low hurdles.

Alex Barge and Hudson Ray tied for high jump honors, while Bill Douglas won the 880 for the Chiefs.

“Pontiac’s only ‘muff’ of the day came in the final 880-yard relay,” said Bob Hoerner of the Lansing State Journal, “when a dropped baton by the already-champions kept the Chiefs from getting more points.”

At season’s end, this 1955 track team was quickly identified as the greatest in school history.

Learning to fly

While he was born in Starkville, Hayes Jones was built in Pontiac during an era of prosperity – when the city held a single public high school and employment was strong. His father, Jesse, had followed a younger brother to Michigan for work. Saving enough money after a couple of months, he called for his family to join him. Hayes was 3.

Jones never failed to credit those who helped when discussing the global athletic success that would come.

In a Free Press article from 1996, he recalled his instruction. “I had a good hurdling coach, Ray Lowry … and from what he taught me I’d visualize what I was supposed to do,” said Jones. A record holder at Toledo Scott High School, Lowry was one of the top pole vaulters in the nation while at Michigan Normal (today Eastern Michigan University) during the mid-1930s.

“Mr. Lowry taught me everything I knew about hurdling,” said Jones, when Lowry’s name was mentioned. “When I went to college my coach was a distance expert, but he didn’t know much about hurdling. As a freshman in Pontiac, I ran hurdles but I was very short. Most of my peers were taller and moved much faster than me. But Mr. Schloerke and Mr. Lowry saw my determination and said, ‘Let’s keep him on the team.’ I asked if I could take home a hurdle to practice with during the summer. I lived a mile and a half away. Mr. Lowry said ‘I’ll leave two or three out for you. You can practice with them after you deliver your newspapers.’ So every morning I’d deliver the Detroit Free Press and I would then head over to Wisner Stadium to practice.

“One morning this gentleman was driving past the stadium, and decided to stop. His name was Charlie Irish and he was a recreation supervisor for the city of Pontiac. I guess he’d drive by every morning and see this kid practicing. On this particular morning he stopped, and then every morning he would come.”

Whenever the ‘kid’ knocked down hurdles, Irish would pick them up and put them back in place.

Whenever the ‘kid’ knocked down hurdles, Irish would pick them up and put them back in place.

“Charlie and his wife moved to Sun City after he retired. After college, I would fly to Arizona to thank him every year for giving up his time. There’s a large cemetery off Woodward between 13 and 12 Mile Roads, (where he’s buried),” said Jones, continuing. “Whenever I’d find myself there, I’d look to my right and remember Charlie.”

A fourth figure from Pontiac also loomed large in shaping Jones.

In the fall of 1955, after serving 13 years as principal at Pontiac Eastern Junior High, Francis Staley assumed the role of principal at Pontiac High School. He would remain in the role until the fall of 1967. His new job led to a conversation with the school’s budding track star.

“You have done your homework,” Jones said, laughing. “Yes, that was Principal Staley. He was the one from a personal standpoint that put me on the right track from an academic point of view.

“When he arrived at the high school, he called me to his office. I didn’t know what was going on. I thought he just wanted to meet a state champion,” Jones added, chuckling at the thought. “He had a folder on his desk. ‘I just want to let you know, no student at Pontiac High School can participate in extracurricular activities without passing grades. It appears you are right on the border.’”

Jones told Marilyn Daley of the New York Daily News about the incident for a feature in 1968. At 29, he had recently been named commissioner of recreation for New York City’s “new super-agency, the Parks, Recreation and Cultural Affairs Administration,” working toward giving kids and adults, regardless of income, opportunities for recreation 12 months a year.

“Hayes, you can’t continue in sports with these grades. Do you want to run or do you want to study?” asked the new principal.

“He was going to take me off the team," Jones explained. "Track and field was my whole life.

“That was the turning point of my life,” said Jones some 60 years later, reflecting on that summit and the impending consequences. “I hit the books. If it weren’t for Principal Staley, I wouldn’t have attended college.”

New-found focus

The 1956 track season would cement Jones’ standing as the greatest track athlete in Pontiac school history.

In March, at the Huron Relays, an indoor event hosted at Eastern Michigan’s recently opened Wilbur P. Bowen Fieldhouse, Jones picked up where he left off, winning three events while finishing tied for a fourth. It was an impressive performance to kick off the season.

In early April, Jones again starred at the Saginaw-Arthur Hill Indoor Invitational event at Central Michigan, setting new meet marks in the broad jump and high jump (tying with teammate Hudson Ray). He really opened eyes with a 7.8 time in the 65-yard high hurdles. “The recognized college time in the nation for that distance is 7.9,” noted the Record-Eagle, “so fans can see that he really was moving.”

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, concern was expressed about one athlete dominating prep meets in Michigan.

“There’s considerable agitation among prep track coaches to alter the point system in the state championships,” reported Bill Frank, future sports editor for the Battle Creek Enquirer. “Last year, for instance, Hayes Jones of the Class A championship Pontiac High team scored (the same number of points as) the second place school. … Many coaches feel that relay teams should count double in points, such as in the state swim meet. … Doubling points in relays would offset one school coming up with one outstanding athlete who could win the title by himself, such as Jones. … Also it’s felt it isn’t fair to give an individual seven points for a first place when an entire relay team of four runners can earn no more points as a group for winning.”

That April 21, for the first time in school history, Pontiac sent 17 athletes to compete in the prestigious Mansfield Relays in Ohio. Today the event is known as the Mehock Relays, renamed after the event’s originator, Harry Mehock, in 1972.

“Pontiac’s individual standout is Hayes Jones … who could well become Michigan’s all-time star prep hurdler,” wrote Ed Ackley of the Flint Journal, a week prior to the event. “Pontiac coach Wally Schloerke says he isn’t taking his club to Mansfield with any great hopes of winning the team title. ‘I just want to give the boys a good workout against stiff competition,’ he points out.”

“Pontiac’s individual standout is Hayes Jones … who could well become Michigan’s all-time star prep hurdler,” wrote Ed Ackley of the Flint Journal, a week prior to the event. “Pontiac coach Wally Schloerke says he isn’t taking his club to Mansfield with any great hopes of winning the team title. ‘I just want to give the boys a good workout against stiff competition,’ he points out.”

But seven days later, for the first time in the Relays’ 25-year history, the Mansfield trophy “made its first trip outside the confines of Ohio.” It headed north to Michigan, thanks to “a sterling performance by lithe Hayes Jones,” said Fred Tharp, sports editor for the Mansfield News-Journal in a front page story.

Jones piled up 16 points, winning the 120-yard high hurdles and the broad jump, while placing “second in the 180-yard low timbers. His winning broad jump of 22 feet, 11¾ inches was just 3¼ inches behind the record set by Cleveland’s Jesse Owens in 1933. Jones had equaled the 180-yard low hurdle record of Bill Whitman of Cleveland East Tech in the morning semi finals. Whitman had run 19.4 in 1952.”

“Jones’ two firsts were the only wins authored by Pontiac but the Michigan School took four seconds, two thirds and a fifth” as the school racked up 34½ points. “Jones’ 16 points outscored 92 teams in the huge field.”

(Over 60 years later, Jones is one of only seven Mansfield/Mehock winners who went on to become an Olympic champion.)

A week later, Pontiac won its second consecutive Class A championship at the Central Michigan College High School Relays.

“In the 16-year history of this event the weatherman has seldom co-operated. Saturday was no exception,” stated the Free Press in its coverage of the gathering. “Weekend rains and the pounding feet of nearly 3,000 schoolboys, turned the oval into a quagmire. Despite these conditions, Jones had another fine day.”

The versatile athlete won three events, setting a meet record in the 120-yard hurdles at 14.9 on a rain-drenched track in near-freezing temperatures.

At the Class A Regional at Ypsilanti, Pontiac cruised to a record-shattering victory, scoring 97½ points and 12 firsts across 15 events, and again was expected to dominate the MHSAA Class A meet. To no surprise, Jones starred.

“Already the possessor of the state high hurdles record of 14.5, set last year, Jones bettered it last week for the third time. He cleared the posts at 14.3 (at the regionals) – only three-tenths off the national high school mark of 14,” stated The Associated Press in its preview to the upcoming state championship. Schloerke was quoted as saying that Jones was a “definite Olympic future prospect”.

On May 21, at the Class A and D track and field championships hosted at University of Michigan’s Ferry Field, “Hayes Jones made all those fabled track performances of his official,” stated the Free Press. “The 160-pound Pontiac High senior set two of the six records established, won three firsts and led the Chiefs to their second straight Class A track and field championship. Pontiac rolled to a record 61 points by winning six events and scoring in 10 of the 13 on the program.”

It was the 12th Class A championship by a Saginaw Valley Conference track team in 13 years.

Jones bested a 20-year old mark in the broad jump by more than nine inches (previously held by Lansing Central’s Ted Tycocki), with a leap of 23 feet 8 7/8 inches. He topped his own record in the high hurdles with a mark of 14.4, “won the lows in 19.4 and anchored the winning Pontiac 880-yard relay team for a personal contribution of 19½ points … other Pontiac firsts were won by Hudson Ray in the high jump, with a leap of 6 foot 3 3/8 inches and Bill Douglas, who captured his section of the half mile in 1:59.7.”

“The Pontiac track team should be recorded as the most powerful thinclad team in P.H.S. history - surpassing, if possible, even the undefeated State Championship squad of 1955,” wrote the sports editor of the 1956 Pontiac High School yearbook. Balance and depth, along with individual record-breaking performers, accounted for Coach Schloerke’s ‘dream team.’”

Eastern Michigan and national fame

The conversation with Principal Staley, and Jones’ decision to act, paved the way for life after high school. It was Lowry who suggested that Jones attend his alma mater, Eastern Michigan.

There was interest from larger schools that offered track scholarships. But an athletic scholarship didn’t apply at Eastern.

“We are forbidden to do so by our administration. We have absolutely no scholarships available to athletes as such,” said Eastern track coach George Marshall at the time. Eastern, along with Central Michigan, competed in the Interstate Intercollegiate Athletic Conference with five schools from Illinois.

“My parents said, ‘You’re going to school to get a college education, not to just run track.’ I washed dishes and mopped floors to help my parents pay for college,” recalled Jones. “You had to get in based on academics. I think I would have gotten lost at a bigger school. At Eastern – teachers gave you one-on-one attention. They’d invite you over for dinner. I needed that.

“Back then all the boys had to serve one year in ROTC at Eastern. For some reason, I couldn’t stand at attention for any length of time – I would always get regular demerits. Finally, they said, ‘We’re sending you over to the infirmary to find out why.’ There they found out my left leg was three quarters of an inch shorter than my right. They made me exempt from ROTC, and I was told ‘Go run track.’”

At Eastern, Jones joined 17 returning lettermen on the track team. Standing 5-foot-10, Jones was small for a hurdler, but he quickly made his presence known.

In the opening meet of the winter indoor season, a 62-42 loss to Marquette University, Jones stood out, tying the Hurons’ 65-yard low hurdle mark with a winning time of 7.4 seconds. He also finished first in the high jump and broad jump. By the end of his freshman indoor-outdoor season, he had competed in 58 events and had captured 49 firsts.

In a 54-50 victory over reigning Big Ten champion Indiana in March of 1958, Jones, now a sophomore, tied the world’s record in the 60-yard dash. He also set a new American record in the 70-yard low hurdles and tied the U.S. mark in the 70-yard high hurdles. Instantly, he was thrust to the “forefront of American indoor hurdles.”

In June, he was invited on a trip with a U.S. State Department-sponsored track team that toured Belgium, France and Italy. Again, he absorbed advice and direction from coaches and peers.

Dave Sime, a great Duke sprinter, was on the trip and among those he credited. (Sime later would win a silver medal in the 100 meters at the 1960 Olympics in Rome).

Dave Sime, a great Duke sprinter, was on the trip and among those he credited. (Sime later would win a silver medal in the 100 meters at the 1960 Olympics in Rome).

“I had been dizzy starting … sometimes I’d use my arms right but often I was wrong. He showed me how to use them properly and I’ve been getting away good,” said Hayes in March 1958 after surprising track followers with a victory in the 60-yard hurdles at the National Amateur Athletic Union Indoor event in New York.

An injury suffered in December 1958 of his junior year received play across newspapers around the Midwest.

“I broke the training rules to play basketball and didn’t get caught until I broke my ankle,” said Jones, recalling the time in the New York Daily News article.

“It was a hairline fracture but Eastern had them put a full cast on me. I guess they didn’t want me to do any more damage,” Jones remembered, humored by the memory.

He was back in full form by the end of January 1959, winning two events for the second time in a row at the Michigan AAU track meet at Ann Arbor, including an 8-second flat in the 65-yard high hurdles – a tenth of a second off the world record. By his senior year, he was a national track celebrity, winning the 110-meter high hurdles at the Pan-American games in September 1959, then equaling the world record in the 60-yard indoor high hurdles at the end of January 1960 at the Millrose Games in New York. The news of his record was covered coast-to-coast.

In February, in back-to-back meets staged in Philadelphia and New York, he became the first in history to win both sprint and hurdle events in major indoor meets. Later in the month, he edged Lee Calhoun (the 1956 Olympic gold medalist in the 110-meter hurdles from Gary, Ind., and North Carolina College) in the 60-yard high hurdles at both the 72nd National AAU championships at Madison Square Garden and at the Knights of Columbus meet in New York. In Cleveland in March at the Knights of Columbus meet, he again topped Calhoun in the 50-yard high hurdles, lowering the world indoor mark to 5.9 seconds in the race.

A rivalry was formed. “I had the speed, but not the endurance,” stated Jones, recalling his dominance in the shorter indoor races but Calhoun’s success in the longer outdoor events. “I was leading up to the sixth or seventh hurdle, then I’d hear him coming.”

An Olympic berth

Jones continued to cause I.I.A.C. meet records to fall like dominoes when the outdoor season arrived at Eastern. In July, he earned a place on the U.S Olympic team at the trials at Stanford in Palo Alto, Calif., finishing third behind Calhoun by one tenth of a second, and Willie May (Big Ten hurdles champion at Indiana University) at 13.5 in the 110-meter hurdles. Public fundraising efforts began immediately in Pontiac to raise money to send his parents to Rome to watch their son compete in the Games of the XVII Olympiad. The three – Calhoun, May and Jones – finished in the same order in Rome in September sweeping gold, silver and bronze for the U.S.

After college, Jones accepted a teacher-coach position at Detroit Denby High School while training for the 1964 Olympics. When told by Olympic officials that accepting a coaching stipend could affect his amateur status, he soon transferred to Tilden Elementary in Detroit.

By February 1964, he had posted 50 straight indoor wins, dating back to 1959.

Asked why he preferred indoor racing, Jones told Sports Illustrated, “I’m only 5 feet 10 and outdoors everybody’s bigger than I am. When I get indoors, though, the spring in the boards and the spring in my legs make me 7 feet tall and I’m bigger than anybody.”

Still, there comes a point when experience is no longer a runner’s friend. Despite the success, Jones knew the 1964 season would be his last.

”Now I’m old – mentally. I’ve done everything a man can do as an athlete, and now I’m just repeating,” he told longtime sports journalist Bud Collins of the Boston Globe that February, announcing his plans to retire after the track season. “I won’t be able to keep the competitive edge much longer.” He still had one goal he wanted to meet: “I want to end my career with a gold medal.”

At the All-Eastern Invitational in Baltimore at the end of the month, he grabbed his 55th consecutive indoor victory, flashing “over the 60-yard high hurdles in 6.8 seconds.” The time shattered his previous indoor world record by one-tenth of a second. With the accomplishment, he stepped away from indoor competition.

In July 1964 at preliminary U.S. Olympic trials hosted as part of the World’s Fair in New York, Jones earned his place with the U.S. team. In October, just prior to the Tokyo games, he reminded the press of his retirement plans. “The only way I can go from here is down,” said Jones, now 26 years old. “I’ve sacrificed two months’ salary to come here. I came because I thought I could win. We’ll know pretty soon now.”

Jones qualified for the medal race, finishing second in his 110-meter hurdle preliminary round heat and third in his semifinals race. But he recognized an issue.

“… When I got to Tokyo I realized my training had not been right, that I had not done enough speed work,” Jones told Sports Illustrated in 1968, recalling the moment. “I was not fast enough between the hurdles. … I remember on the last day running up and down in the tunnel under the stadium, trying somehow to develop speed at the last minute. … In that tunnel a coaching friend, Ed Temple (head women’s track and field coach for 44 years at Tennessee State and head coach of the Women’s U.S. Olympic track team in both 1960 and 1964) came up to me and said, ‘Listen, Hayes, forget about your speed. Don’t worry about it. Just run between the hurdles. Just run.’”

“The only thing Hayes Jones recalls from the rainy race,” wrote Kathleen Gray, referring to the championship battle in a 2004 Free Press article, “was lunging toward the tape. It took longer in those days to figure out who crossed the finish line first, especially with the photo finish of the three top contenders …”

“The only thing Hayes Jones recalls from the rainy race,” wrote Kathleen Gray, referring to the championship battle in a 2004 Free Press article, “was lunging toward the tape. It took longer in those days to figure out who crossed the finish line first, especially with the photo finish of the three top contenders …”

Depending on the source, it took 30 minutes – or was it more – for officials to declare a winner.

“It seemed like 45 minutes before the pictures were in and the lights began to flash on the scoreboard,” Jones said to SI. “Then it came: ‘First place, J…O…N…E…S…’ I can’t tell you the feeling, the thrill of it.”

Fellow countryman Blaine Lindgren finished second, while Anatoly Mikhailov of the Soviet Union ended the race third.

Jones had won his desired gold medal. And then, he gave it away.

Olympic hero comes home

That November, upon his return, Jones presented his Olympic gold medal to the youth of Pontiac during a ‘Salute to Youth’ rally at Pontiac Northern, the city’s newest high school. It still is on display at Pontiac City Hall. The donation was meant to “inspire kids to reach for their dreams,” said Jones.

“When I matriculated to the fourth grade, our principal gathered us together and said, ‘Now that you’re in the fourth grade you can participate in sports.’ The Kiwanis Club sponsored basketball, football and track,” Jones said.

“Because of that, I was able to find my passion. If not for the Kiwanis Club, I doubt I would have been able to find that. What made Pontiac so great was their belief in giving their time. A great community starts with volunteers.”

Today, there are two medals on display.

“The bronze, I had originally donated to the Detroit Children’s Museum under the Detroit Public Schools for permanent display but each time I went to visit, it was in storage. After three times reminding them that it should be on display, I asked for it back and donated it to the city of Pontiac. So now, kids making field trips to city hall will see two Olympic medals laminated and encased in the wall when they visit.”

As he told SI in 1968:

“It wasn’t the medal that mattered, don’t you see? It was the experience.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

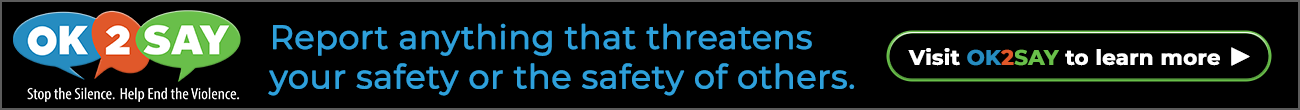

PHOTOS: (Top) Clockwise from left: Hayes Jones presents his Olympic medal to Pontiac mayor William H. Taylor in 1964, Jones leaps a hurdle while at Eastern Michigan, Jones at Pontiac High and Jones goes over the high jump bar while at EMU. (2) As noted, Jones and Willie Wilson warm up before a Pontiac practice. (3) Jones with his Pontiac coaches in 1956. (4) Jones, far left, accepts trophies at the Mansfield Relays. (5) Jones on the cover of his View-Master series on physical fitness. (6) Jones sprints to the finish of his Olympic gold medal win. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)

'Over Here,' Athletes Gave to WWI Effort

March 28, 2018

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

In a nation at war, the needs of many outweigh the desires of a few.

Among the many noble sacrifices for the greater good was Michigan’s spring high school sports season of 1918.

The United States’ entry into “The Great War” (today commonly known as World War I) came on April 6, 1917, 2½ years after the war had begun. First elected President of the United States in 1912, Woodrow Wilson earned re-election in 1916 under a platform to keep the U.S. out of the war in Europe. The sinking of the British passenger ships Arabic and Lusitania in 1915 caused the death of 131 America citizens, but did not invoke entry into the conflict. However, continued aggressive German actions forced a reversal in policy.

“The present German submarine warfare against commerce is a warfare against mankind,” stated Wilson in an April 2 special session of Congress, in requesting action to enter the war.

A huge baseball fan, President Wilson recognized the value of entertainment and athletics during a time of crisis. Major league baseball, America’s pastime, completed a full schedule in 1917. A former president at Princeton University, on May 21, 1917, Wilson addressed the value of school athletics in a letter to the New York Evening Post.

“I would be sincerely sorry to see the men and boys in our colleges and schools give up their athletic sports and I hope most sincerely that the normal courses of college sports will be continued so far as possible, not only to afford a diversion to the American people in the days to come when we shall no doubt have our share of mental depression, but as a real contribution to the national defense. Our young men must be made physically fit in order that later they may take the place of those who are now of military age and exhibit the vigor and alertness which we are proud to believe to be characteristic of our young men.”

“I would be sincerely sorry to see the men and boys in our colleges and schools give up their athletic sports and I hope most sincerely that the normal courses of college sports will be continued so far as possible, not only to afford a diversion to the American people in the days to come when we shall no doubt have our share of mental depression, but as a real contribution to the national defense. Our young men must be made physically fit in order that later they may take the place of those who are now of military age and exhibit the vigor and alertness which we are proud to believe to be characteristic of our young men.”

Despite the highest of hopes, the requirements and realities of war deeply impacted life in the U.S. soon after.

In February of 1918, a proposal was circulated by Dr. John Remsen Bishop, principal of Detroit Eastern High School and president of the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association, to abolish spring athletics at Michigan high schools. Due to a labor shortage brought on by the war, the states, including Michigan, needed help on farms, harvesting crops from spring until late fall. The action might also affect the football season of 1918.

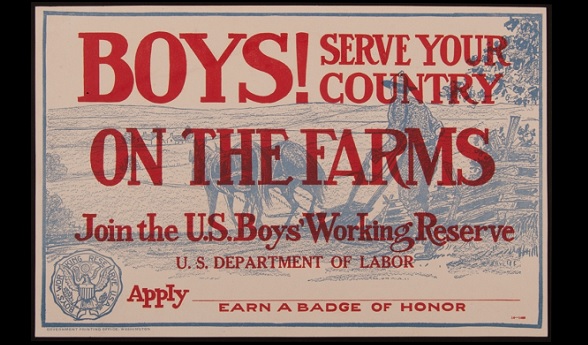

The Boys’ Working Reserve, a branch of the U.S. Department of Labor, was organized in the spring of 1917 and designed to tap into an underutilized resource to help address that labor deficiency. “Its object was the organization of the boy-power of the nation for work on the farms during the school vacation months.”

While the idea was popular among schools around Detroit, due to the lack of public commentary from outstate school administration, it was expected that the proposal would meet at least some opposition when the M.I.A.A. gathered on Thursday, March 28 in Ann Arbor during a meeting of the state’s Schoolmasters Club.

Less than two weeks prior to the March meeting, Michigan Agricultural College made an announcement that would impact one aspect of the coming spring sports season.

“The department of athletics of the Michigan Agricultural College begs to inform the high schools of the state that plans for the annual interscholastic track meet, which was to have been conducted here in June, have been given up this year – not through any desire on the part of this department to discourage athletics, but because this is a time when we can and should devote our resources to better uses,” said coach Chester L. Brewer of the Aggies to the Lansing State Journal. “It would hardly be sound judgment for us to make our usual elaborate plans for this meet while our government is appealing to all of us to economize and exercise the utmost thrift. Neither is it wise policy to encourage unnecessary traveling upon the railroads, or to ask high schools of the state to make any expenditures other than those which are absolutely necessary.”

Earlier in the year, similar news had come from the University of Michigan.

In January of 1917, the University of Michigan had announced plans for an elaborate annual high school basketball invitational, designed to identify a Class A state champion. Billed as the “First Annual Interscholastic Basket Ball Tournament,” the March event hosted 38 teams. However, influenced by the war, a decision had been made not to run a second tournament in 1918. Instead, on March 27, Kalamazoo Central and Detroit Central, two of the state’s top teams, were invited to Ann Arbor for a hastily arranged contest at U-M’s Waterman Gymnasium. The schools had split a two-game series during the regular season. Kalamazoo won the season’s third matchup, and while not official, declared itself 1918 Michigan state champion.

Into this environment of patriotism and uncertainty, school administrators arrived in Ann Arbor for the Schoolmasters gathering. There, in the morning, the membership heard a presentation from H. W. Wells, assistant and first director of the Boys’ Working Reserve. “The heart of the nation, rather than the hearts of the nation, is beginning to beat. War is making us a unit,” said Wells, discussing the aim to recruit boys between the ages of 16 and 21 to help provide food for the allies in Europe and at home in the United States.

“Wells told of the need for the farmers to sow more wheat, and plant more corn,” reported the Ann Arbor News, “and in the same breath he told of great corn fields all over the country, where last year’s corn still lay unhusked, because of a lack of farm labor.”

“Wells told of the need for the farmers to sow more wheat, and plant more corn,” reported the Ann Arbor News, “and in the same breath he told of great corn fields all over the country, where last year’s corn still lay unhusked, because of a lack of farm labor.”

It was estimated that 25 percent of the nation’s farm workforce was now active in the armed forces.

The proposition was brought to the M.I.A.A. by Lewis L. Forsythe, principal at Ann Arbor High School, who would soon establish himself as a guiding force in high school athletics. The proposal “was discussed thoroughly.”

“This session is usually a stormy one, because of contentions that arise over rulings that affect schools in different ways,” said Adrian superintendent Carl H. Griffey to the Adrian Daily Telegram, “but this meeting was a serious one in which all matters were related to our national welfare and passed by unanimous votes.”

So, one day after the conclusion of the abbreviated state basketball championship contest, the spring prep sports season in Michigan came to an abrupt halt. Michigan’s male high school students were asked to work to support the war effort.

“Chances are that they will remain there for the duration of the war,” stated the Lansing State Journal in response to the action. “At the meeting … it was talked of quitting football because of the need of the boys staying on the farms till the latter part of November. This is highly probable. If it is passed upon then Michigan high schools will have but one sport, basketball.

“Whether intra-mural sports will replace the representative teams is not known. This form of athletics demands the attention of a great number of teachers to tutor the different class organizations. The teachers are taxed to the limit at present and cannot give the time to sports. Organizing farm classes and Liberty bond teams is taking the teacher’s spare moments. … But still athletics are needed, as the war has demonstrated, and physical training should be instituted from the kindergarten to the university.“

“Those lads who leave for the farms the first of May,” wrote the Port Huron Times-Herald, “will be in better condition when they return home from the fields and cow lanes than they would (have) had they remained in the city until June batting the leather pill.”

The fate of the 1918 football season would not be known until late August.

In late June, the 29th Governor of Michigan, Albert E. Sleeper, thanked the estimated 8,000 students who had joined the ranks.

“To you soldiers of the soil I would say this, that I am as proud to address you as I would be to address any of the boys who are bearing arms for their country. You have proved that you are true patriots, for you have started out to do exactly what your country has asked you to do – the thing which you can do best for your country at this time.

“To you soldiers of the soil I would say this, that I am as proud to address you as I would be to address any of the boys who are bearing arms for their country. You have proved that you are true patriots, for you have started out to do exactly what your country has asked you to do – the thing which you can do best for your country at this time.

“Every day, in the rush of official work, I think of you Reservists as you work on the farms, just as I think of our soldiers who are in training camps or ‘over there.’ And I am just as proud of you as I am of them. So are all the people of Michigan.”

It was estimated “the boys who last spring left their high school studies and as members of the United States Boys’ Reserve have helped the Michigan division to add $7,000,000 to the food production of the nation.”

In September, Byron J. Rivett, secretary of the M.I.A.A., announced that, based on a vote of member high schools, prep sports would be resumed in the fall. The Detroit News celebrated the news that “moleskins and pigskins will be in evidence and the grand old game will be a part of the autumn’s entertainment.”

In October, in Grand Rapids and Detroit and other cities across the state, officials gathered to honor those who served as part of the “Michigan Division of the Reserve” and to award bronze badges in recognition for their contribution to the war effort.

World War I officially ended on November 11 with the signing of the armistice. Armistice Day, today known as Veteran’s Day, was first celebrated in 1919. In total, an estimated 16 million were killed during the war.

“Four million ‘Doughboys’ had served in the United States Army with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Half of those participated overseas,” said Mitchell Yockelson in Prologue magazine, a publication of the National Archive. “Although the United States participated in the conflict for less than two years, it was a costly event. More than 100,000 Americans lost their lives during this period.”

More than 5,000 of those casualties had come from Michigan.

***

To the surprise of the world, a second war arrived in 1918. This one did not discriminate based on geographic or political borders. It would take more lives than World War I.

To the surprise of the world, a second war arrived in 1918. This one did not discriminate based on geographic or political borders. It would take more lives than World War I.

Globally, the Spanish Flu pandemic arrived in three waves, one in the spring, one in the fall of 1918, and a third arriving in the winter of 1919 and ending in the spring. It, too, would impact high school and college athletics in Michigan and beyond, as countless football games across the nation were cancelled in an attempt to help reduce the spread of the disease.

In the end, an estimated 675,000 would die in the United States from the virus. In Michigan, hundreds succumbed in October 1918 alone. In Detroit, between the beginning of October and the end of November, “there were 18,066 cases of influenza reported to Detroit’s Department of Health. Of these, 1,688 died from influenza or its complications.” Worldwide, an estimated 50 million were killed by the Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) The U.S. Department of Labor recruited high school students to work on farms as soldiers went oversees to fight World War I. (Middle top) A Working Reserve badge. (Middle) Lewis L. Forsythe. (Below) Another recruitment poster for the Working Reserve shows a man plowing a field while war rages in the background. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)