Michigan Boys Take the Swimming Plunge

November 30, 2018

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

It was late March. Dressed in his black silk swimsuit adorned with an orange letter “J,” James Dingman stood 18 inches above the waterline, perched on a spring-less board. In 60 seconds it would be over.

With his arms outstretched into an inverted “V,” he dove face first into the 90-foot swimming pool. The tank, 30 feet wide, and located on the campus of Michigan Agricultural College (now Michigan State University), was the largest of its kind in the Midwest and measured 15 feet longer than a standard competitive pool.

“The aim of all plungers should be to leap as high into the air as possible and as far out as an open jack-knife will carry,” wrote Tom J. Clemens in the 1919-20 edition of the Wilson Athletic Library Official Swimming Guide, the bible of instruction and rules for swimming, diving, water games and lifesaving. “Nearly all plungers dive too flatly,” added the coach of the Detroit Y.M.C.A. swimming team. “A plunge is only as good as the dive.”

How long Dingman remained under water or at what distance he surfaced is not recorded. According to Clemens, a dive might bring the body to within six inches of the bottom of the pool. The best plungers remain under water as long as possible, angling upward at 40 degrees just as the force of the dive is spent. Record holders would surface 40 to 50 feet out into the water.

Upon surfacing, as per the rules of the event, Dingman glided along the surface, without the aid of propulsion from his arms or legs, for a measured distance of 63 feet. The mark fell two feet short of his performance in the prelims. Still, it was the best of the day and earned him a first place finish at the 1925 team state swimming championships.

While its origins are unclear, the plunge for distance dates back to at least 1865. In 1904, it appeared as an Olympic diving event, and then disappeared from the games. By the 1920s, it was rapidly losing popularity. The plunge appeared only twice in the Michigan high school state title meets. The first time was in 1924 in what was Michigan’s first swimming and diving championships. Sanctioned by the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association (MIAA), the immediate predecessor to the modern-day Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA), a total of nine teams – Northern, Northwestern and Southeastern, all of Detroit; Highland Park, Ann Arbor, Jackson, Lansing, Battle Creek Lakeview and Flint Central – took part in the event.

While its origins are unclear, the plunge for distance dates back to at least 1865. In 1904, it appeared as an Olympic diving event, and then disappeared from the games. By the 1920s, it was rapidly losing popularity. The plunge appeared only twice in the Michigan high school state title meets. The first time was in 1924 in what was Michigan’s first swimming and diving championships. Sanctioned by the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Association (MIAA), the immediate predecessor to the modern-day Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA), a total of nine teams – Northern, Northwestern and Southeastern, all of Detroit; Highland Park, Ann Arbor, Jackson, Lansing, Battle Creek Lakeview and Flint Central – took part in the event.

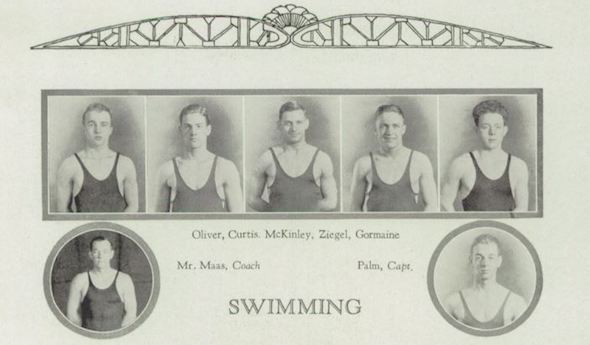

The 1925 championships was the first run by the MHSAA. Also staged at the M.A.C. pool, it featured a 10th team – Detroit Cass Tech. Dingman’s performance, combined with teammate Dick Seydell’s surprising first-place finish in the fancy diving competition and Jack Redfield’s second in the 100-yard freestyle, helped Jackson High School earn an unexpected runner-up finish in only its second year of competition.

Following the actions of the NCAA, the state association removed the plunge from the schedule of competition prior the 1926 championship meet.

Fancy diving and my plunge into uncharted waters

My ‘job” as MHSAA historian, (which is really just a fascination with prep sports history) has always been to fill in holes that surface when I, the various members of the MHSAA staff or the state’s television, radio or newspaper media, seek answers to a question. I’m a detail guy, who earned my living as a business analyst compiling, normalizing and studying data. I love diving deeper into information, completing lists and unearthing stories to tell.

From the first trophy awarded by the MHSAA in 1925, and then for the next 20 years, the state’s 35 team swimming championships never strayed beyond the borders of four Michigan counties: Wayne, Washtenaw, Calhoun and Jackson. Two of those counties, Washtenaw and Calhoun, accounted for 24 of those 35 titles.

Within those borders, only eight schools claimed titles during those two decades, with two schools combining for 18 of those awarded championships.

Detroit dominates

The Detroit area dominated statewide competition in the earliest days. The metro area boasted many of the state’s finest high schools, offering students, male and female, a wide array of athletic facilities and opportunities. During the 1920s, the schools dominated across a variety of sports, including swimming where Detroit Northwestern, Detroit Northern and Highland Park battled for annual city, state and, often, mid-west supremacy.

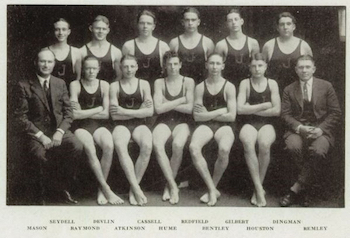

From 1925-1927, Detroit Northwestern, coached by Bert Maris, won the MHSAA’s Open Class swimming competitions, featuring all schools regardless of enrollment. A former coach at University of Michigan and Notre Dame, Maris accepted the position of athletic director at the newly-opened Northwestern High School in 1914, and stayed for 28 seasons before retiring in 1942. Like many mentors from the era, he coached multiple sports, winning state titles in basketball, track, and swimming. Over the years he worked with an amazing number of athletes, including football legend Knute Rockne and track stars Eddie Tolan and Willis Ward. Maris’ teams actually won four swimming titles in a row, as Northwestern topped Jackson in that 1924 MIAA prep championship. That meet featured eight events. Besides the plunge, and fancy diving, it included the 50, 100 and 220-yard freestyles, the 50-yard breaststroke, the 50-yard backstroke, and the 120-yard relay.

From 1925-1927, Detroit Northwestern, coached by Bert Maris, won the MHSAA’s Open Class swimming competitions, featuring all schools regardless of enrollment. A former coach at University of Michigan and Notre Dame, Maris accepted the position of athletic director at the newly-opened Northwestern High School in 1914, and stayed for 28 seasons before retiring in 1942. Like many mentors from the era, he coached multiple sports, winning state titles in basketball, track, and swimming. Over the years he worked with an amazing number of athletes, including football legend Knute Rockne and track stars Eddie Tolan and Willis Ward. Maris’ teams actually won four swimming titles in a row, as Northwestern topped Jackson in that 1924 MIAA prep championship. That meet featured eight events. Besides the plunge, and fancy diving, it included the 50, 100 and 220-yard freestyles, the 50-yard breaststroke, the 50-yard backstroke, and the 120-yard relay.

The 1925 meet, in which Dingman competed, included the same events and added the 300-yard medley relay, comprised of the 60-yard backstroke, 60-yard freestyle, 60-yard breaststroke and 120-yard free. While Northwestern repeated as team champion, Gurdon Guile of Flint Central “was the star of the meet, with a first in the 100-yard freestyle and a second in the 50-yard freestyle.”

OPEN CLASS

|

Year |

Champion (Coach) |

Runner-Up |

|

1925 |

Detroit Northwestern (Bert Maris) |

Jackson |

|

1926 |

Detroit Northwestern (Bert Maris) |

Highland Park |

|

1927 |

Detroit Northwestern (Bert Maris) |

Highland Park |

|

1928 |

Highland Park (Grant Withey) |

Detroit Northern |

The 1926 championships featured 10 Michigan high schools, including Belding, a newcomer to state swimming circles. Horace Craig, later a star swimmer at Michigan State, trimmed eight seconds from the 220 freestyle record in leading Northwestern to its third straight title in 1926. He again topped the mark in the preliminaries in 1927 as Northwestern posted 57 points, outdistancing runner-up Highland Park by 34.

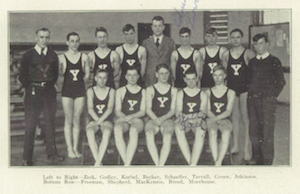

In 1928, Highland Park jumped to the forefront, qualifying 10 of 26 swimmers in preliminary competition – more than twice the number of any other school – then unseated the four-time champions in the finals to win the competition. The Polar Bears topped six state meet records (including Craig’s 220 freestyle mark) along the way. Then, led by Louis Lemak and Bob Klintworth, future swimmers at the University of Michigan, Highland Park repeated as champion in 1929 when MHSAA competition was split into Class A for the state’s largest schools based on enrollment and Class B-C-D to handle all other schools with swim programs in the state. Roosevelt High, one of two high schools in Ypsilanti, grabbed the Class B-C-D crown, with East Grand Rapids finishing second.

In the spring of 1930, Central High School in Ypsilanti eked past East Grand Rapids by a single point to top a field of seven schools competing for Class B-C-D honors. It was the first of four straight titles for Ypsilanti Central and their coach, James Schaffer, over a five-year span. (In 1932, the Indians finished runners-up to River Rouge. Rouge, in turn, finished second to Ypsilanti in 1931, 1933 and 1934).

In the spring of 1930, Central High School in Ypsilanti eked past East Grand Rapids by a single point to top a field of seven schools competing for Class B-C-D honors. It was the first of four straight titles for Ypsilanti Central and their coach, James Schaffer, over a five-year span. (In 1932, the Indians finished runners-up to River Rouge. Rouge, in turn, finished second to Ypsilanti in 1931, 1933 and 1934).

Detroit Northwestern returned to the pedestal in 1930, earning another title against a field of 14, this time with Leo S. Maas as coach. It would be the last swimming title awarded to a Detroit Public League school.

With the arrival of the 1930-31 school year, Detroit public schools withdrew from state interscholastic competition, to focus only on intramural contests between other Detroit city schools. Vaughn S. Blanchard, who took charge as Director of Health and Physical Education for the Detroit Public Schools in 1929, cited in the decision his belief that there was an unhealthy overemphasis on competitive athletics. The voluntary exile would last for the next 30 years and recast competition within Michigan prep athletics.

Maas’ teams would continue to dominate Detroit swimming, winning 7 of 9 City League championships. In September of 1938, he joined the staff of Wayne University as swimming coach, leading the Tartars to national prominence in the 1940s. He spent 20 years at the school, renamed Wayne State University in 1956.

Battle Creek Takes Charge

Charles McCaffree, Jr. was born in South Dakota and learned to love swimming at the YMCA pool in Sioux City. He followed his brother to the University of Michigan, earning three varsity letters under internationally-known swimming coach Matt Mann. Following college graduation in 1930, McCaffree was hired at Battle Creek Central as swimming coach in 1931. For the next six years, 1931-1936, his Bearcats teams won Michigan swimming titles. All were in Class A, with the exception of the 1935 tournament, when, because of the Great Depression, only a single title was awarded. A total of 139 swimmers from 14 teams competed in the state’s 12th annual meet, held at the intramural pool at the University of Michigan.

The MHSAA returned to two class championships in the spring of 1936. Ypsilanti Roosevelt returned to the winners’ circle, besting Ypsilanti Central by two points, 38 to 36, while winning four first places in the eight-event meet.

The MHSAA returned to two class championships in the spring of 1936. Ypsilanti Roosevelt returned to the winners’ circle, besting Ypsilanti Central by two points, 38 to 36, while winning four first places in the eight-event meet.

In September 1936, McCaffree returned to U-M to take over the Wolverines program while Coach Mann attended to his seriously ill father in Leeds, England. McCaffree’s teams at Battle Creek had won 53 dual meets and lost only three. He helped build the district’s junior high swim program and turned out 14 prep All-Americans, (including Dobson “Dobbie” Burton, captain of Michigan’s 1941 NCAA championship swim team and later, a very successful swim coach at Evanston Township High School in Illinois). With Mann’s return to the helm at Michigan in February 1937, McCaffree accepted the head swimming coaching position at Iowa State, where his teams won four Big Eight Conference Championships.

In 1942, “Coach Mac” was hired by Michigan State athletic director Ralph Young to head the Spartans swim team. For the next 28 years, he guided the team as head coach, winning eight straight Central Collegiate Conference championships prior to State’s entry into the Big Ten. In 1957, he led MSU to its first Big Ten swimming title. Before retiring as coach in 1969, “his student-athletes earned All-American honors 322 times, won 34 Big Ten titles, and claimed 22 NCAA titles. Six individuals qualified for the Olympics.” In 1979, the university named the pools within the Intramural-West Building in his honor.

CLASS A

|

Year |

Champion (Coach) |

Runner-Up |

|

1929 |

Highland Park (Grant Withey) |

Detroit Northern |

|

1930 |

Detroit Northwestern (Leo. S. Maas) |

Detroit Northern |

|

1931 |

Battle Creek Central (Charles McCaffree) |

Lansing Central |

|

1932 |

Battle Creek Central (Charles McCaffree) |

Kalamazoo Central |

|

1933 |

Battle Creek Central (Charles McCaffree) |

Lansing Central |

|

1934 |

Battle Creek Central (Charles McCaffree) |

Lansing Central |

OPEN CLASS

|

Year |

Champion (Coach) |

Runner-Up |

|

1935 |

Battle Creek Central (Charles McCaffree) |

Dearborn Fordson |

CLASS B-C-D

|

Year |

Champion (Coach) |

Runner-Up |

|

1929 |

Ypsilanti Roosevelt (Howard Farnslow) |

East Grand Rapids |

|

1930 |

Ypsilanti (James Schaffer) |

East Grand Rapids |

|

1931 |

Ypsilanti (James Schaffer) |

River Rouge |

|

1932 |

River Rouge (Benny Goodell) |

Ypsilanti |

|

1933 |

Ypsilanti (James Schaffer) |

River Rouge |

|

1934 |

Ypsilanti (James Schaffer) |

River Rouge |

Ypsilanti, Jackson emerge

McCaffree’s replacement at Battle Creek, John Vydareny, led the Bearcats to a seventh consecutive title in 1937. The city of Ypsilanti retained control of the Class-B-C-D title, as Ypsilanti Central dethroned Roosevelt High 71-54. It was the first of three consecutive by Central High and coach James Schaffer.

“More than 200 high school swimming stars churned the Michigan State college pool today as they warmed up for trials in the 15th annual Michigan High School Athletic association championship swim,” noted The Associated Press in 1938 pre-event coverage.

A broadcast, featuring a running account of the meet, was recorded in East Lansing that Saturday and brought to Battle Creek for an 11:00 p.m. broadcast on radio station WELL-AM. Designed to give listeners “the pool’s edge atmosphere of the meet,” the program was replayed on Sunday evening “to give those who did not attend, and those who retired too early to hear the Saturday night program.”

A broadcast, featuring a running account of the meet, was recorded in East Lansing that Saturday and brought to Battle Creek for an 11:00 p.m. broadcast on radio station WELL-AM. Designed to give listeners “the pool’s edge atmosphere of the meet,” the program was replayed on Sunday evening “to give those who did not attend, and those who retired too early to hear the Saturday night program.”

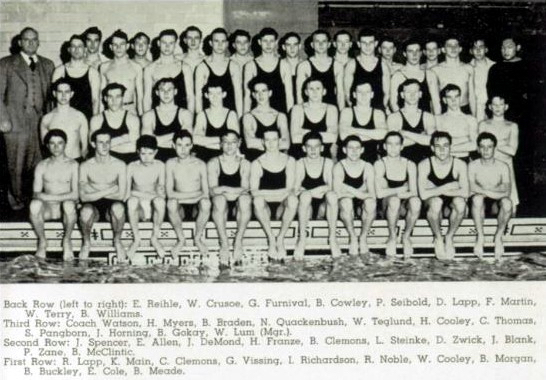

Jackson, which lost the Five-A league title to Battle Creek, emerged as the Class A winner. Both schools brought 22 to the event.

“Jackson dethroned the Bearcats…in the Michigan State college natatorium and the difference between an eighth successive crown and runner-up position … was disqualification of the Battle Creek Medley relay team in the preliminaries. The Bearcat medley trio finished a full half lap in front of the field … in record time … but it was ruled out …”

Jackson finished with 39 points, followed by Battle Creek with 32. The Vikings would repeat as Class A champions in both 1939 and 1940. Coach Elwood Watson’s swimmers would pick up a fourth title in 1942. Battle Creek Central added three additional titles to their total with wins in 1941, 1943 and 1944. Because of World War II restrictions, only 13 schools entered the Class A meet and five competed in Class B-C-D in 1943, while 14 schools participated in the Class A meet in 1944 at Michigan State, and six schools chased honors in the Class B-C-D competition at the University of Michigan.

With the absence of Detroit schools during the 14-year span, 1931 through 1944, a member of the 5-A League – comprised of Battle Creek, Jackson, Ann Arbor, Lansing Eastern and Lansing Central – controlled Michigan’s Class A swim title during that time. On nine occasions during that period, the 5-A also placed the state runner-up.

I n Class B-C-D, Ann Arbor University High emerged as a swimming power, finishing as runner-up to Ypsilanti Central in both 1938 and 1939. Guided by University of Michigan assistant swimming coach Harvey Muller, the Cubs ended the city of Ypsilanti’s grip on the smaller school title in 1940.

n Class B-C-D, Ann Arbor University High emerged as a swimming power, finishing as runner-up to Ypsilanti Central in both 1938 and 1939. Guided by University of Michigan assistant swimming coach Harvey Muller, the Cubs ended the city of Ypsilanti’s grip on the smaller school title in 1940.

“University High’s crack free-style quartet of Bill Koch, Earl Bryant, Jim Gordy and Max Tobias nosed out Central in the final relay to overcome a 43-42 lead which Ypsilanti held prior to the event.”

With the win, “the Ann Arbor tankers scored 52 points, one more than Central … It was Central’s first defeat in the state meet in the last four years.”

Ypsilanti Central topped Roosevelt in the 1941 state meet, this time under the guidance of coach Christy Wilson. University High won the first of five straight titles, with Muller as coach in 1942 and the legendary Matt Mann guiding the team from 1943 to 1946. Among the winners in 1943 was Matt Mann, Jr., who clipped five seconds off the meet’s 200-yard freestyle record. He would later be named a four-time All-American at Michigan and compete on the university’s 1948 national championship swim team. Following graduation, Mann, Jr. coached swimming and diving at Lansing Sexton High School.

Times Change

Post World War II saw many changes to society, cities, and, within competitive swimming, new record setters and coaching legends emerged. In 1980, a separate boys tournament was added to the MHSAA menu for Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. The grouping of schools moved from classes to divisions in 2003, and in 2008, a third division was added.

Today, ownership of MHSAA boys swimming & diving titles has geographically traveled a bit farther, but still to only 12 of Michigan’s 68 Lower Peninsula counties.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) The 1930 Detroit Northwestern team was among early state swimming powers. (2) Jackson's 1925 team also was an early force in the sport. (3) Bert Maris. (4) The 1930 Ypsilanti team. (5) Charles McCaffree, Jr. (6) The Michigan Agricultural College pool, in 1921. (7) The 1940 Jackson team. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)

Pioneer's Hills Leave 'Lasting Impression'

April 25, 2014

By Geoff Kimmerly

Second Half editor

More than 40 years coaching some of Michigan’s top high school athletes has earned Denny and Liz Hill thank-yous from a variety of sources now that they've announced their job is finally done.

Like from the former swimmer now in Washington, D.C., who wrote to Denny to explain – tongue-in-cheek, of course – how swimming at Ann Arbor Pioneer prepared her to handle the long hours and grouchy bosses that come with being a lobbyist in the nation’s capital.

Or from the group of parents who saw the Hills at a recent restaurant opening and thanked them for showing their kids that they too were key parts of Pioneer’s swimming and diving teams – even though those athletes weren't among the many MHSAA championship or All-America-level contributors.

“You get notes from people explaining the wonderful things you did for them, and you didn't realize what you’d done,” Denny Hill said. “I kept telling Liz (again, tongue-in-cheek), I don’t understand why all these kids come out. I’m mean to everybody. ... But I’m getting that (appreciation) back from kids, and mostly parents. The parents kept saying that no matter how good (their kids swam), they were part of the team, and we felt good about that. I think that’s important, especially at the high school level.”

All joking aside, there are few who have helped push an entire sport, statewide, to an elite level while keeping those high school values in mind like the first couple of Michigan high school swimming.

The Hills retired as Pioneer’s boys swimming and diving coaches during this winter’s postseason banquet. Denny served as head coach of the boys team for 45 years and the girls for 38 before leaving the latter after 2010 – combined, he has a dual meet record of 1,011-128-2 and led the boys team to 15 MHSAA championships and the girls team to 16. He also guided 240 athletes – including eventual Olympic medalist Kara Lynn Joyce – who earned All-America honors from the National Interscholastic Swim Coaches Association.

Liz, his wife of 31 years, served as his boys assistant for 14 seasons and co-head coach for seven and girls assistant for 23 years and co-head coach of that team for four. She was part of all the girls championships and the majority won by the boys.

Those accomplishments rightly have highlighted the tributes both have received locally and beyond over the last two months – including when Denny was inducted into the NISCA Hall of Fame in March. But they tell only one side of their contributions to the sport they've lived for half a century.

“Denny and Liz have left a lasting impression on high school swimming, both locally and nationwide. Their accomplishments with their teams can be seen in the trophy cases and record boards across the state, but they have done so much more for the swim community,” said Bloomfield Hills’ girls coach David Zulkiewski, who also serves as president-elect of the Michigan Interscholastic Swim Coaches Association.

“They have volunteered and dedicated hours to the improvement of the sport and to benefit current and future athletes. Their leadership roles with MISCA and NISCA have provided us with instruction, inspiration and guidance that will last into the future.”

Been there, seen it all

Denny Hill has seen it all, and Liz has seen most of it during their decades in the pool.

Denny graduated from Lansing Eastern High School in 1962, and then swam at Michigan State University until graduating in 1966. After a year of student teaching at Jackson Parkside and then 1967-68 as boys coach at Ferndale, Denny took over the Pioneer swimming and diving program. He also taught chemistry until retiring from the classroom in 2007.

(Side notes: Denny’s father Harry Hill was a highly-respected labor leader and education activist Lansing and had a high school on the city’s south side named after him posthumously in 1971. Denny’s mother Berniece served as Lansing’s postmaster general during the late 1960s and 1970s.)

(Side notes: Denny’s father Harry Hill was a highly-respected labor leader and education activist Lansing and had a high school on the city’s south side named after him posthumously in 1971. Denny’s mother Berniece served as Lansing’s postmaster general during the late 1960s and 1970s.)

Liz, formerly Liz Lease, was a standout sprinter for the Pioneers until graduating in 1976, and then earned All-America honors at the University of Michigan before finishing studies in 1980.

She taught and coached in Texas for two years before returning to Ann Arbor, marrying Denny in 1983 and helping his teams from time to time until becoming an assistant for good a few years later.

Coaching together, they created a fine-tuned system. Liz would work with the younger or less experienced swimmers, and Denny worked with the advanced group. One year Liz had 44 girls in hers; often, Denny would work with 22-28. They’d come together to practice starts and turns and for meets, all getting a chance to compete in some fashion be it in additional heats or junior varsity competition.

After two runner-up MHSAA Finals finishes in three seasons from 1974-76, Pioneer’s boys won their first Class A title under Hill in 1977 – which ended up being the first of six straight championships and eight in nine seasons. The girls followed back-to-back runner-up finishes in 1983-84 with their first championship in 1985, and that win started a string of six in eight seasons. Pioneers’ girls also won Class A/Division 1 titles from 2000-08, the last two with Denny and Liz officially as co-coaches.

Pioneer athletes continue to hold all-MHSAA Finals records in the 50 and 100 freestyles (both by Joyce) plus the 200 and 400 relays.

“The thing that sticks out in my mind about Denny is that he always had a bigger vision of everything. His vision of a particular athlete’s potential, in and out of the pool, exceeded theirs,” said Eastern Michigan University men’s swimming coach Peter Linn, who has led the Eagles to 21 Mid-American Conference championships and swam for Denny Hill’s club teams as a youth and against Pioneer as a high school coach in Upper Arlington, Ohio; he also coached the Hills’ son Steven at EMU. “His vision of being the best high school team was more than just being state champions; it was about being national champions. He held everyone including himself accountable to the pursuit of that vision.

“In doing this, he and Liz not only succeeded in producing amazing teams and terrific individuals at Pioneer and in Ann Arbor, but they also raised the bar on high school swimming in Michigan – and the results were instrumental in raising the overall level of swimming in the state. They left you two choices: rise to the occasion and be your best, or get left behind.”

Far-reaching impact

The Hills and Linn’s friendship is like many in swimming – no MHSAA sport, arguably, has as many long-serving coaches and long-cultivated connections.

Maureen Isaac knew the Hills long before agreeing to coach the girls swimming and diving program at brand-new Ann Arbor Skyline in 2008 – her husband Stu Isaac was Liz Hill’s coach at U-M. But Maureen also ended up with four athletes who previously would've gone to Pioneer, and yet – “never once did (the Hills) not help me,” she said.

She first called Denny right after getting the job. That turned into him sending her all of Pioneer’s meet results from the previous year so she had some background on opponents coming into that first season. He and Liz continued to welcome Skyline athletes to their annual summer program, and never ran up the score against Skyline’s teams – although Pioneer could’ve won big those first few seasons.

Isaac remembers in particular the first meet against Pioneer, when its swimmers stayed in the pool until the last swimmer for both teams finished a race. It’s a practice her much-improved program has adopted, among others she’s admired from across town.

“I called them up literally to beg them to stay,” Isaac said. “I’m as competitive as the next guy; I want to win as much as the next guy. But how they've done it ... you look at the Facebook postings, the responses from alumni when they found out (the Hills) were leaving, and not one person was talking about winning a state title. They talked about the amazing influences (the Hills) had on their lives.”

That influence extends far beyond Ann Arbor.

Denny and Liz’s athletes and former assistants have gone on to coach at high school and college levels in Illinois, Oregon and Ohio among other states, with the recent Michigan footprint including South Lyon boys and girls coach John Burch and Saline former girls and current boys assistant Pete Loveland.

The Hills also have long played significant roles in their state and national coaching associations and the national rule-making body. Denny was on the National Federation of State High School Associations' rules committee during the 1970s when it was coordinated by now-MHSAA Executive Director Jack Roberts. Denny also remains a NISCA director for the zone including Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa and Wisconsin.

“For the 40 years I've been involved with high school swimming in Michigan, Denny Hill has been the coach that I have tried to emulate. His integrity and manner of coaching have been an inspiration to all of us,” said East Grand Rapids coach Butch Briggs, who has led boys and girls teams to a combined 28 MHSAA championships. “His quiet leadership and love for both the sport and his athletes has served as a model for all to aspire to. Although he will be missed, his legacy will continue to inspire those of us involved in Michigan high school swimming.”

The big picture

Liz Hill said she “just follows along in the shadows,” an extension of their program that has allowed more students to participate.

She’s being more than modest.

In addition to taking over as Pioneer’s co-coach, she continues to manage the Huron Valley Swim Club – which teaches and trains 300 aspiring swimmers. Denny and Liz have served as back-to-back presidents of MISCA – Liz is finishing up her term this spring – and she also will receive a NISCA outstanding service award next year.

Although swimming and diving is not in the public eye as frequently as more media-covered sports, it still has plenty of politics to hurdle. The Hills are known as voices of reason – voices the rest of Michigan and beyond has been wise to heed.

“A lot of times, people don’t always see the big picture. They think in terms of their own athletes, their own teams, and sometimes you have to look at what’s best for everyone,” Liz Hill said. “Denny has done so much for swimming, been involved for so long. Because he has had success, people tend to listen to what he has to say.”

Denny Hill said he likes to think that Ann Arbor has served as the capital of swimming in the state. He also played a giant role in the community’s non-school swimming scene, including starting Club Wolverine – recognized as one of the top programs of its type in the nation.

He’s taken high school teams all over Michigan, not only to have Pioneer face the best but hopefully to provide those opponents the opportunity to test themselves as well.

But even then, some of the favorite memories might be different than expected.

Like when former swimmer Eric Troesch, then an assistant coach, was able to jump into the EMU pool with the rest of the girls team after they won another MHSAA title – and despite suffering a serious spinal cord injury a year before that had left him temporarily paralyzed. Or this season’s boys team, which had a combined grade-point average of 3.6 and was made up, again, of the kind of students Denny would've taught in his chemistry classes.

This week, Hill remembered a conversation with Linn years ago that framed many of his and Liz's efforts.

“He said, ‘It sounds to me like we had more fun when we didn't have as good of teams than others we (had),’ and that hit home for me,” Hill said.

“I don’t think we have the pressure to win from the schools and parents; we’re not getting all the write-ups in the papers like for basketball and football, and the kids are doing it not so much for the glory of it, but for self-improvement. The kids look at the record book and it’s a motivation thing, and really for those kids they’re pretty motivated to go on and be the leaders of the country because they work hard, they strive for the team atmosphere type of thing, and they have a fine sense of community and helping people.

"I think that’s really neat.”

PHOTOS: (Top) Denny and Liz Hill (center) cheer on their team during the 2013 MHSAA Division 2 Finals. (Middle) The Hills are retiring after more than three decades coaching together at Ann Arbor Pioneer. (Top photo courtesy of HighSchoolSportsScene.com. Middle photo courtesy of Ann Arbor Pioneer Swimming and Diving.)