Soccer, Hoops Next to Seed Using MPR

August 6, 2019

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

As the topic of seeding for MHSAA Tournaments continues to swirl in the air of numerous committee meetings on an annual basis, one of the primary concerns continues to focus on the simple question: “How?”

The MHSAA for years has been working behind the scenes on potential formulas which could best be used as a standardized tool to assist in measuring strengths of teams in a given sport.

This spring, the MHSAA introduced the Michigan Power Rating in the sport of Boys Lacrosse. The Representative Council approved limited seeding beginning in 2019-20 for girls and boys soccer and girls and boys basketball, and MPR will be the metric to determine which two teams must be seeded on opposite sides of District brackets in those sports.

“The boys lacrosse tournament has been seeded since it was added as an MHSAA-sponsored sport in 2005. The seeding is done by committee based on several criteria, one of which was statewide power rankings generated by a third-party website. In the Fall of 2018, that website ceased operation – it was the perfect opportunity for the MHSAA to develop its own data-driven, purely objective ratings system and incorporate that data into the seeding criteria,” said Cole Malatinsky, administrative assistant for the sport.

“The benefits of the new MPR system have been already mentioned – it is MHSAA controlled, simple, objective, and transparent, and it can be used by other MHSAA sports in the future.”

MPR is a computer rating formula similar to the popular RPI rating. MPR provides a way to measure a team’s strength relative to other teams, based on games played against other MHSAA tournament teams, largely on the strength of their opponents’ schedules. MPR is purely objective using only the game results listed on MHSAA.com – there is no subjective human element.

What is the basic MPR formula?

MPR is calculated using wins, losses and ties for games played between teams entered into the MHSAA tournament. The final MPR number is 25% of the team's winning percentage, plus 50% of its opponent's winning percentage, plus 25% of its opponent's opponent's winning percentage.

MPR = (.25 x W%) + (.50 x OW%) + (.25 x OOW%)

The MPR formula can be applied easily to other MHSAA team sports.

What game data is included in the formula? What game data is not?

MPR looks only at results between opponents entered into the MHSAA postseason tournament. Wins, losses and ties in multi-team shortened game tournaments (lacrosse, soccer) also count. Forfeits also are counted as wins and losses.

MPR does not use the specific scores of a game or the margin of victory in a game. The location of a game is not included in the MPR formula, and the formula weighs results at the beginning of the season the same as results at the end of the season. Scrimmages are not included.

Why use the MPR formula?

Different rating systems have been used in the past or have been recommended to the MHSAA. We wanted to have a rating system where the data was controlled and stored in house and could be used for any sport featuring head-to-head competitions.

With its own rating system the MHSAA also can control the different components of the formula, thus keeping the tenets of scholastic competition at the forefront (like not including margin of victory in the formula). Finally, by listing all scores and team schedules online, as well as showing the MPR calculator on each team schedule page, the ratings are transparent and can be replicated easily.

CALCULATING MPR

What are the detailed components of the MPR formula?

You need three numbers to calculate your MPR: winning percentage (W%), opponent’s winning percentage (OW%) and opponent’s opponent’s winning percentage (OOW%).

How do you calculate winning percentage (W%)?

Divide the number of wins by the number of total games played. A tie is worth half a win. For MPR purposes, find the winning percentage against all teams that will play in the MHSAA tournament (MPR W%). Games played against out-of-state teams, varsity “B” teams, junior varsity teams, non-school club teams, and any other non-MHSAA tournament participants should not be included when calculating winning percentage. W% should be an easy number to calculate.

How do you calculate opponent’s winning percentage (OW%)?

Average the winning percentages of a team's opponents. When calculating the winning percentage of a specific opponent, use the opponents "Adjusted Winning Percentage" (ADJ W%). Adjusted winning percentage eliminates all games the team played against that opponent (as well as its games against non-MHSAA opponents).

For instance, if the team beat an opponent with an overall record of 4-1, use a record of 4-0 (1.000) for that opponent. If the team lost to an opponent, use a record of 3-1 (.750). Find the ADJ W% for all opponents, and then take the average. If a team plays an opponent team twice, that opponent’s ADJ W% will be counted twice.

OW% is not calculated via the combined record of the opponents; instead take the average of all opponent’s winning percentages.

How do you calculate opponent’s opponent’s winning percentage (OOW%)?

Use the same process described above, except calculated for the opponents of a team's opponents. This number is much harder to manually calculate, so the OW% for every team is listed on the MPR page of the MHSAA website.

Again, simply take the average of all opponent’s OW%.

How often is MPR calculated?

MPR is calculated about every five minutes. Enter a score and a minutes later the team MPR and the MPR of all the team's opponents will update.

How much will my MPR change throughout the season?

You will see wild MPR swings in the beginning of the season, but after about 10 games played your MPR will start to level out. At 20 games played you will see very little movement with each additional game played.

My score is missing. How can it be added?

This is a crowd-sourced system. Any registered user of MHSAA.com can add a missing score. ADs, coaches, parents, students and fans all can login and enter a score for any game.

What are some common errors when calculating MPR?

When calculating your team’s winning percentage, only include games against MHSAA-tournament teams. When calculating your opponent’s winning percentage, don’t include the games they played against you. When calculating ties, count the game as a half-win and half-loss.

What happens if a game is cancelled?

Because the MPR system works off of averages, it will not make a difference in the final MPR if a game cannot be rescheduled. It would not penalize, nor benefit, any team involved in that scenario.

USING THE WEBSITE

Where can I find game scores?

A list of statewide scores for all sports can be found in the MHSAA Score Center. To find a schedule for any team click on “Schools & Schedules” in the top navigation bar, search for the school, then once on the school page click the sport. You can also see a list of all schools (with links to schedules), on the statewide MPR list.

“We continue to have great success in score reporting for varsity boys lacrosse contests. While we state that schedule submission and score reporting to MHSAA.com are required, athletic directors and coaches understand that in order for MPR data to be accurate, we need consistent and accurate score reporting,” said Malatinsky. “MHSAA.com is now the primary site for high school boys lacrosse schedules, results and ratings in the state.”

How should I use the statewide list of teams and MPR?

Linked to the boys soccer page (and eventually to be added for both basketball pages and girls soccer) is a statewide listing of all Michigan Power Ratings (MPR) for teams entered into the MHSAA postseason tournament for that sport. Linked on the MPR page is an explanation of the District draw formula, describing when and how teams will be placed on the bracket.

The MPR data updates every five minutes. Click on the column headings to sort the data. You also can use the drop-down menu to show teams in one Division, or type a District number in the box to filter teams for that District (Region for boys lacrosse).

You also can click on any school name to go to its schedule page.

How do I read the school schedule page?

The schedule at the top of the page shows the date and opponent for all scheduled games, and results for games already played. If results are missing, click “Submit Score” to add a game score.

Below the game schedule is the MPR Calculator. The calculator is split into three sections. The first section shows the three MPR component scores for the team, as well as the team’s current MPR score. The second section shows the MPR information for the team’s opponents – specifically, for the opponents the team already has played (actually, for games where scores have been submitted). Only these games are included in the MPR calculation.

The third section highlights future opponents. The MPR data for future opponents are not used in the MPR calculation for the team.

PHOTO: East Kentwood and Ann Arbor Skyline play for last season’s Division 1 boys soccer championship.

'Trail-Blazing' Girls Make Convincing Case, Earn Deserved Due on Basketball Court

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

March 31, 2022

After two years of pandemic uncertainty, with the completion of the MHSAA’s annual Girls Basketball Finals, it is time for a glance back to 50 years ago and the state’s first girls basketball tournament.

The 2022 weekend was a delight, with fans, student sections, and pep bands returning to cheer and motivate. With a half-century of perspective, a deeper dive into the history of the girls tournament shows those first years were truly trailblazing times. It’s easy to forget that things we take for granted today, like in-season ranking of the state’s top teams, Miss Basketball Awards, season-ending all-state squads, and college scholarships for female scholars/athletes weren’t always a part of the prep world, or even that prep athletics for girls as we know them today didn’t exist before the early 1970s.

“Before the passage of Title IX in 1972, fewer than 300,000 females participated in athletics nationwide, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations,” noted Geoff Kimmerly of the MHSAA.

“During the 2019-20 school year – the most recent not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic – nearly 76,000 girls competed in athletics in Michigan alone, filling more than 120,000 spots on teams for 750 high schools statewide.”

A Changing World

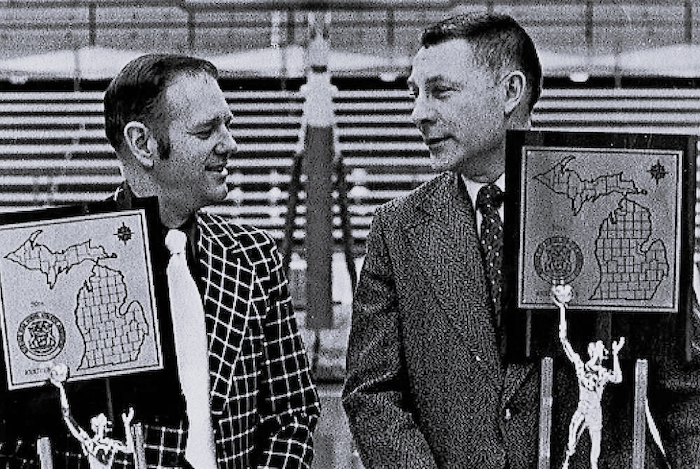

In December 1971, Allen W. Bush, state director for the Michigan High School Athletic Association, spoke to a group of about 600 athletic directors and principals at the Civic Auditorium in Grand Rapids. There he advised schools to prepare their budgets for girls sports in the coming years.

“I anticipate there will be a fairly wide program for girls next year run on state level competition,” he explained.

Brice Durbin, the executive secretary of the Kansas State High School Activities Association, and today remembered as the “father of girls high school sports in Kansas,” was the event’s principal speaker. Kansas had already made the moves Michigan would soon embark upon.

“Girls want to participate in sports and, you know, they’re pretty doggone persuasive,” said Durbin, telling the story of one school official who stated a girls athletic program would never happen in his school. A year later, the individual called Durbin, asking how to start a track program.

“It seems one girl who was about to become a ninth grader had been traveling around the country and doing well in meets. And it also turned out that her father was the head of the board of education.”

At the time, skiing was the only sport with sponsorship for girls at the statewide level in Michigan. Gymnastics came next in March of 1972.

That same month, Pat Murphy of the Lansing State Journal wrote, “Another bastion of male chauvinism may be crumbling. High School basketball – long dominated by the boys – is attracting girl cagers in ever growing numbers.

“A state tournament for girls teams may even be in the future, according to Lonnie D. Lowery, assistant state director of athletics for the (MHSAA).”

Administration Challenges

The MHSAA understood sponsoring postseason championships for the girls would present challenges, seen and unforeseen.

One of the immediate issues to surface with the sponsorship of athletics for girls was a shortage of coaches. According to MHSAA regulations, only women could serve as coaches for the girls, but in May of 1972, the MHSAA removed the restriction. It would take a couple of years, but the state would see a broad shift.

Another issue, stated Vern L. Norris, associate director of the MHSAA, was there weren’t many women officials. The Association’s list – spanning all sports – included just 160 names in July of 1972. The Association hoped the sponsorship of girls tournament games would inspire additional interest. “…(W)e’d be tickled to have them,” said Norris.

In October 1972, the first girls tennis tournament was conducted. Next up was swimming, first held that November. Golf followed in May of 1973, then track.

On May 31, 1973, details appeared in the State Journal announcing final approval of an MHSAA sponsored girls basketball tournament, scheduled to begin in late November. Just two years prior, 296 schools stated they sponsored girls basketball in Michigan. According to report, the number now totaled 507.

Like the boys tournament, which dated back to 1917 in Michigan, there were to be four champions christened with the title games played in December at four high school gymnasiums around the state. The schedule was chosen for the event, said Norris, “because most schools start girls basketball early in the fall since the girls do not compete in football. Many girls then compete in volleyball after Christmas, and a state girls’ volleyball tournament will be staged in the spring, starting in 1974,’ he added.

That scheduling decision would be challenged, and ultimately, changed.

Changes on the Court

Girls basketball had been played in Michigan as far back as 1898. The traditional girls’ rules known to most prior to the 1970s – six players on the floor, three stationed at each end of the floor – were established in 1938. With the announcement of a postseason, those rules were replaced. Action on the court across Michigan would now be nearly identical to the boys’ game.

“Many girls teams were already using the boys rules,” said Bush. Standardizing to five-player ball, many felt, made girls basketball easier to understand. “The rules we’ll be using were written by women coaches and adopted by the National Federation of State High School Athletic Associations.”

By June, the number of schools that indicated they would sponsor girls basketball teams that coming fall had swelled to 629.

By June, the number of schools that indicated they would sponsor girls basketball teams that coming fall had swelled to 629.

Money-wise, the MHSAA expected that the girls postseason would operate in the red, but the Association’s focus was long-term. At the time, financial support for the Association came solely from profits derived from the annual boys basketball tournament. Then, as now, no government funds or tax dollars supported the MHSAA, a private, not-for-profit corporation of voluntary membership.

“Only two years ago it cost the MHSAA $25,000 over and above ticket receipts to conduct the state wrestling tournament,” noted Jim DeLand in the Benton Harbor Herald-Palladium in 1973, “but last year, because of greatly increased fan support, the deficit was down to only $3,000. The state baseball tournament initiated two years ago has been much more successful in all respects than anticipated, although it still is not operating in the black.”

“The potential is here (for girls basketball) to be a very popular event,” Norris said, adding that the Iowa girls tournament (where the coaches were “almost all male,” and six-player basketball would continue through the 1993 season) nearly overshadows the boys tournament.

That first year of MHSAA postseason sponsorship, there was flexibility in when the girls opened and ended their season. Most schools started their season in September. However, the Detroit Catholic League chose November to begin play.

Changes in Sports Coverage

Back in early November of 1972, another State Journal article entitled “Michigan Closing the Gap in Girls Sports” had appeared in print. The article had compared Michigan’s “attitudes toward girls’ high school sports to Iowa. This one acknowledged the effects of pressure being brought by the state’s athletes and physical education teachers, as well as the success of club sports programs found in many of the more affluent areas of Michigan.

“Substantial numbers of them have come to feel, in the last few years, that intramural activities simply aren’t enough – that girls’ sports should be carried the next logical step into the interscholastic arena, as boys’ athletics were many decades ago. There was really nothing that prevented it from happening before, except the disinterest of prep girls themselves. Rightly or wrongly, the vast majority of them believed (or were taught to believe) that true competitive athletics were no place for proper young women.”

A few days later, in the same paper’s “Letters to the Editor” column, reader Christine Convissor cut through the rhetoric, and asked, “If Michigan is closing the gap on girls sports, why not report on some of the games?”

Concluding, she wrote, “On behalf of the girl cages in the Lansing area alone (as I know there are many more around the state) I would say we have the talent. Now, how about some publicity?”

Convissor, as it turned out, was a senior basketball player at Lansing Catholic Central at the time but had noted the gender disparity in coverage. Recalling the moment five decades later she mentioned, “My dad got a kick out of this letter. He was a real estate agent and worked nights, so when he arrived at the games it was something special! Even more so now.”

Convissor’s father died unexpectedly of a heart attack just a few months after the letter’s publication.

When the light switch was flicked on, it was unrealistic to expect instant parity with boys’ sports programs. But the push for equality was certainly a challenge for many people.

The state’s sports prep administrators would wrestle with the changes. As illustrated by the growth in sponsorship by schools of girls athletics, the arrival of a basketball program was completely new in many districts. In quite a few areas, where the girls’ game had all but disappeared or evolved into intramural play decades before, attracting fans to games was a task.

For many newspapers and their sportswriters, interscholastic athletics for females, and the resulting demand for column inches in the sports section, was an unwelcome invasion.

Some coaches were quick to recognize the challenges the athletes faced, on the court and off.

At St. Joseph, in southwest Michigan, the “first season girls varsity basketball, comparable to boys varsity sports, began” with a team during the 1972-73 school year, according to the school’s yearbook. The first team did well, finishing with a 10-1 record. But newspaper coverage of the season is all but nonexistent.

Coach Fred Knuth took over the girls team at St. Joe the following year but had only four days between being hired to coach the squad and establishing his roster.

Knuth came from a family of 11 kids. “Most of us all played sports,” he recalled, 50 years later. “We were a family that loved competition.” (Kim Knuth of St. Joseph, Fred’s niece and daughter of his brother Dan, was named Michigan’s Miss Basketball in 1994.)

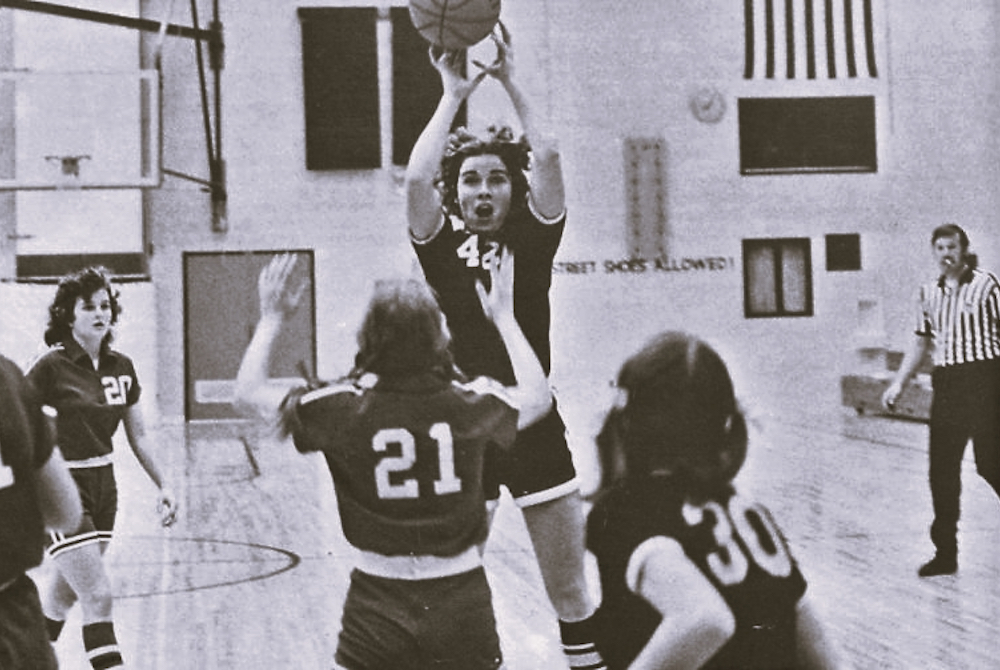

Among those Fred coached that first year was his sister, 6-foot center, Chris. His top player was guard Melanie Taylor, a senior who possessed a jump shot, unusual among girls at the time.

“The girls haven’t had the organization and training like the boys and their game experience is very limited,” Knuth told the Benton Harbor Herald-Palladium in an October article that summarized activity among the area’s girls cage teams.

Knuth was coaching girls for the first time. “Their biggest problem is that they don’t know how to react under pressure. And the only way they can get this kind of experience is through programs in the lower grades. That’s something we are working on now and it will pay off in the future.”

“We did not get much coverage at all (during the season) until we got to the tournament,” recalled the 82-year-old Knuth. “In the (Regional Semifinals), the newspaper picked us up.”

The Bears were an impressive 16-0 and scheduled to play Adrian in the Thursday night doubleheader, played at Kalamazoo Central High School. According to the postgame article, written by Herald-Palladium sports editor Jim Deland, Chris Knuth “plucked off 27 rebounds … with star guard Melanie Taylor tossing in 13 first-half points,” as St. Joseph led Adrian, 32-10 at the intermission.

“Substitutes carried most of the load the rest of the way,” noted DeLand. “All told, 12 different girls scored for St. Joe,” in the team’s 55-34 win.

“They talked about all the girls, and what we were trying to accomplish,” remembered Knuth, his pride on display in the memory. “That was pretty nice.”

The Bears fell to East Lansing, 50-48, in the Regional Final. St. Joe led, 48-47, with 50 seconds remaining to play. Taylor finished with 26 points, including all the team’s points in the first quarter.

“That was my biggest regret, that we couldn’t win that one,” said Knuth, who was the only male coach in the tournament at Kalamazoo. His girls finished 17-1 on the year. “I had a very good rebounding team, but the ball didn’t seem to bounce our way. But that’s sports.”

“Sex bias in the local newspaper? The girls varsity basketball team was mean; but, except for their opponents and the relatively sparse crowds that turned out to see them, no one seemed to know about it. Very little newspaper coverage was lent to the undefeated team,” stated the St. Joseph High School annual at the end of the school year.

Opportunity

The complaint about lack of coverage was common. In March of 1973, a new magazine debuted. “The Sportswoman,” a bi-monthly launched by 26-year-old Marlene Jensen, broached the “male-dominated World of sports.”

Nationally, there were very few women reporting sports. Occasionally, Michigan papers included a few column inches from female stringers, but it would take more time before one of the state’s major dailies hired a woman for the sports staff.

“I started covering sports in 1977 as a stringer for The Grand Rapids Press,” recalled Ruth Butler, “mostly prep.”

“I did not aim at sports for a career. A friend was working as a stringer, mentioned they wanted someone to take scores and game info on the phones. I wanted a summer job. After a couple weeks on the phones, I was assigned a feature, and then another.

“In ’78, a new sports editor made it a priority for The Press to cover girls sports. Perhaps not at the same level as the established boys, but seriously and visibly. One of his first moves: Hiring the first female for a newspaper staff in Michigan. I was that person and managed high school sports coverage.”

Eventually, more females would follow.

Tournament Time

With the opening of the Districts, some were quick to proclaim the tournament a “failure.”

“Crowds reported to UPI by tournament managers Saturday night, ranged from a near invisible 60 at Muskegon Oakridge to 1,000 who showed up at Gladwin and Battle Creek Lakeview,” wrote United Press International’s Richard Shook. “Most of the districts sampled had turnouts ranging from 200 up to 600 – and most of the tournament directors managed a wan ‘we hope to break even.’“

Only 86 people attended the Class A District championship between St. Joseph and Niles, according to the Herald-Palladium. Played at Benton Harbor, the game, unfortunately, was scheduled against season-opening boys basketball games at the two schools.

“‘Two hundred persons showed up to watch Hudsonville Unity Christian nip Hudsonville, 55-52, and… Roger Borr (athletic director at host Holland West Ottawa) was ‘crying the blues,’” continued Shook.

But not all reports were downbeat.

“’We drew 800-900 for three games,’ said Tom Eaton, principal at Mason Country Central, of that school’s Class C District. ‘We’ll make a profit.’

‘’’We broke even of maybe even made a little money,” Joan Shirkey reported of her Harper Woods Bishop Gallagher District. ‘We had crowds of 300-400.’

“We had 347,” football coach and athletic director Dick Soisson said of his Kalamazoo District title game. “We drew just under 1,000 for the three nights.”

Soisson was among those who could see the bigger picture and envision the potential of the tourney.

“’I can see how this thing can grow,” he told Shook. “Parchment had never won a boys district game – now their girls have won a district title.’”

Before the opening of the Quarterfinals, Hal Schram of the Detroit Free Press reported that some tournament contests in greater Detroit “drew as few as 70 or 80 spectators a game,” and that “there wasn’t a single crowd that hit 800 fans,” in the area.

At East Kentwood High School, “just outside of Grand Rapids where the Class B finals will be staged,” athletic director James Czanko told Schram that he couldn’t understand the apathy. “The parents don’t even come to the games.”

At East Kentwood High School, “just outside of Grand Rapids where the Class B finals will be staged,” athletic director James Czanko told Schram that he couldn’t understand the apathy. “The parents don’t even come to the games.”

“The small schools, the Class C and D squads, are drawing the biggest crowds,” noted the veteran prep writer.

“That’s easy to understand,” says William Bupp of Alma, tournament director of the Class D Semifinals and Finals. “Girls’ basketball belonged to the small towns long before you saw it in the big cities.”

The Class A Semifinal and championship games were played at Grand Blanc. East Kentwood hosted the Class B contests, while Class C was scheduled at Owosso. Alma High School welcomed the Class D games. All the final championship games kicked off on Saturday, Dec. 15 at 2:30 p.m.

More Than Missed Shots and Dollars and Cents …

Behind closed doors – but occasionally in print – some mocked the changes happening in the world of sports.

“The Class A battle at Grand Blanc ‘lured’ 635 fans and Owosso ‘packed in’ 270 for the Class C tilt,” wrote Bruce Johns in a column in the Flint Journal following the tournament. “Each of the boy’s championship games last March at Ann Arbor drew 13,609 spectators.

“Why the low turnouts? Because it’s the first year? I think the reason is because it’s boring. Before you want to fry me, hear me out. I covered only two tournament games but came up with these statistics: 130 turnovers, or, 32½ per team per game and 65-for-251 shooting for a .358 average.

“Female coaches claim their teams play good defense. That’s easy to say when the other team can’t handle the ball or shoot. Ballhandling and shooting form the offense in basketball. Maybe some parents and a few school loyalists will cheer their locals on but the average fan doesn’t care to watch mediocrity.

“But you girls should be proud because you finally got this thing off the ground,” concluded Johns. “And, in the future, it should really go over big with development of basketball programs.”

… Rather, it’s About What Came After

The tournament was about more than numbers. The perspective of Detroit Cass Tech coach Shirley Burke put the existence of the postseason into proper perspective.

“The tournament has definitely increased interest in girls’ basketball,” she told Luther Keith of the Detroit News, “from the spectators point of view and given girls more incentive. In the past, nobody cared if we won or lost, and the tournament gives the girls something to shoot for after the regular season.

Dominican coach Sue Kruszewski concurred: “The tournament has been very exciting for the girls. It’s just a thrill meeting different teams from outside the city. The tournament has been overdue, and I’m just glad it’s finally here.”

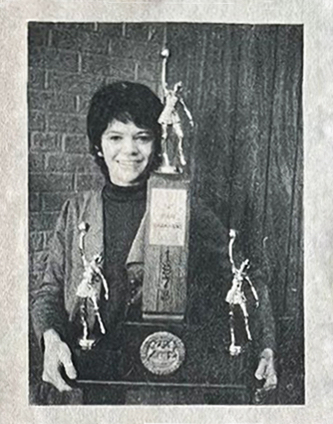

Parents, brothers, sisters, and some 500 fans greeted the Ewen-Trout Creek girls upon their return from their 1,200-mile round trip to Alma.

“A welcome-home celebration with all the trimmings, including a motorcade of automobiles to greet them at Kenton (21 miles away) and a huge pep rally in the high school gymnasium finished off a perfect weekend for the all-conquering undefeated Class D State champion Pantherettes … here Sunday night,” declared the Ironwood Daily Globe.

“We thought we had seen everything when our boys brought home the state championship a year and a half ago, finishing unbeaten in 26 straight games but now our girls have won a state title too, by finishing undefeated in 23 straight games, said Superintendent Ray Rigoni, Jr.”

Veteran basketball official Ben Manning of Trout Creek also celebrated the moment.

“The father of Sandy Manning and former stars Jim and Bob Manning, he beamed like a proud father would, saying, “I cheered harder and longer for these girls than I did for the boys. … It seemed that our family wouldn’t have anybody left to cheer for when the boys got through at Trout Creek High School, but we hadn’t counted on our girl getting a chance to play.”

At Unity Christian, “the Championship Crusaders were given a parade in their honor from Jenison to Hudsonville,” wrote Dave Bos in the Grand Valley Shoppers Guide, “and at a special assembly Monday, the big State Title Trophy was given to the school by coach (Sue) Constant.”

(Bos, boys JV coach and varsity assistant, would later serve as athletic director at Unity Christian. His daughter, Jane, would later play sports at Unity, then work for 27 years at The Grand Rapids Press, serving as Preps Editor in later years for the paper.)

Two of the schools, Dominican and St. Lads – would repeat as state champions in 1974. And, in both cases, their coaches would move up.

At Dominican, Kruszewski’s teams had won 303 of 366 basketball games. In May 1977, she left the school, recruited to start the women’s athletic program at the University of Detroit.

After nine years at Hamtramck St. Ladislaus, coach Gloria Soluk moved to Wayne State as head coach for three seasons, then on to the University of Michigan in September of 1977. At Michigan, she replaced Carmel Borders, who had guided Ann Arbor St. Thomas to the MHSAA Class D Semifinal round in 1973.

“It’s been one of my dreams for years,” Soluk told the Michigan Daily. An alum, she had earned a master’s degree in counseling and guidance at Michigan. “I love U-M both for its academics and its athletics.”

Standing Ovation

One player from this first tournament - Melanie Megge – altered the opinions about girls basketball for many people, by illustrating what would be coming their way in the future.

A 5-5 guard, Megge broke the Class A championship game wide open for Dominican, scoring 16 points in the fourth quarter on her way to a tournament-high total of 38. With sensational outside shooting, “she smashed forever the myth that girls can’t play basketball as well as boys,” stated The Associated Press story on the title game. “She seemed equally at ease driving the baseline for twisting layups with either hand, hitting jumpers from the top of the key or playing defense in the Dominican press. Leading 26-23, the senior combined with backcourt teammate, junior Lynn Chadwick (16 points), to bust open the game against Grand Rapids Christian.”

“She could do it all – dribble, pass, play tight defense, and most of all, shoot,” wrote Bob Cooper of the Livingston County Daily Press and Argus, one of the harshest critics of the girls’ game prior to the contest. (Earlier in the same article, Cooper had expressed shock that “tournament officials were actually going to entrust half of this game to the judgement of a female” referee.) “Melanie … received a standing ovation when she left the game. I’m proud to say this reporter was one of those standing.”

“Girls high school basketball, at least at the championship level, is of good quality and highly entertaining. Even the referee with the dress did a nice job.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS (Top) Melanie Taylor (42) from St. Joseph was one of the first stars after the MHSAA began sponsoring girls basketball. (Middle) Vern Norris, left, and Allen Bush hold the 1974 boys basketball championship trophies. (Below) Hudsonville Unity Christian girls basketball coach Sue Constant shows the Class B championship trophy won by her team. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)