'I Play Every Game for Him'

September 18, 2013

By Geoff Kimmerly

Second Half editor

EAST LANSING – A Parma Western shot streaked by Josh Flamme’s reach Tuesday night, seemingly on its way to becoming one of few to make it past him and into the net this season.

But – as if shoved off course – the ball caromed off a post, keeping another shutout intact.

The Mason senior remembers similar scenarios over the last few years. Dives with no chance of reaching the ball – until he feels it smash into his hands. Stops he never could have made without an extra push.

He doesn’t always believe his luck. But he has an explanation.

Walt Flamme died four years ago this spring, four months before the first games of Josh’s high school career. But he goes with Josh every time the all-state keeper heads into the goal box, a conversation partner when the ball is on the other side of the field and a source of strength when an opponent is bearing down on the Bulldogs’ net.

“I’m always just like, ‘Come on man. If you’re going to help me out, you should do it now,’” Flamme said.

“He never saw me play in high school. But I play every game for him, and he has the best seat in the house. He’s helped me out any way he can.”

Flamme is in his third season starting for Mason, ranked No. 3 in Division 2 this week. He’s the latest of a string of all-state keepers who have anchored the team’s defense over the last 12 seasons, and he’s going to graduate as one of the most accomplished. His 41 career shutouts rank eighth in MHSAA history – nine off tying the record – and he’s given up only three goals this season in leading the Bulldogs to a 10-0-1 start. He’s also the kicker on Mason’s undefeated football team.

He’ll be in goal Tuesday when the Bulldogs face Eaton Rapids in their second annual Compete for a Cause game, a fundraiser for the Children’s Center at Lansing’s Sparrow Hospital with donations to be used by families with children receiving cancer treatment.

Mason will wear yellow, symbolizing pediatric cancer. Eaton Rapids will wear blue for prostate cancer, an illness Greyhounds coach Matt Boersma’s dad Jeff has battled. And Flamme will wear orange to symbolize his father’s fight against leukemia, which Josh remembers during his team’s moment of silence before every game and as he points to the heavens once he takes his spot at the back line.

He’s been a keeper since third grade and a perfect fit. He’s Mason's best athlete, and at 6 feet tall can get to shots that might fly over others. He’s got the best work ethic Mason coach Nick Binder and assistant Kevin Gunns have witnessed during their seven seasons running the program, and as a communicator he’s a coach’s dream. “Of our four captains, he’s by far the most vocal,” Gunns said, “and the one the younger kids look up to.”

After turning 18 over the weekend, Flamme also is an adult who perhaps was forced by circumstance to grow up faster than he would’ve liked. Binder believes Flamme shows an elite level of dedication when compared to other high school athletes, and with that an elite level of maturity as well.

“I don’t want to be just bragging about him. But he’s my hero,” said Tracy Flamme, Josh’s mother. “After his dad died and everything, he could’ve become ... not a nice person. But he didn’t. It almost made him stronger, I think.

“His dad would be very proud of him. I’m so proud of him, I could just bust.”

Starting from scratch

Walt Flamme didn’t know a thing about soccer when his son chose that sport over karate as a kindergartner. Walt was a football player, the back-up quarterback and kicker at Okemos during his high school days.

But he became Josh’s main practice partner, pushing the extension pole of a vacuum into the ground a few feet from the flag pole in their back yard to create a makeshift goal and then firing shots at his son. Walt also was the dad who stayed to watch every practice, and Josh would wake up late at night to find him looking up drills on the computer.

“He didn’t know what the heck was going on, but he learned,” Josh said. “He did his work and tried to help me out as much as he could.”

“He didn’t know what the heck was going on, but he learned,” Josh said. “He did his work and tried to help me out as much as he could.”

By the end of middle school, Flamme was an experienced club player and part of an elite team out of Detroit. The path was paved for him to become Mason’s next great keeper.

Valuable mentors have helped him reach that goal. Recently graduated Michigan State keeper Jeremy Clark has been a go-to source for advice and an extra push when needed. Two former high school standouts, Mason and Olivet’s College’s Ethan Felsing and Caro’s Brandon Wheeler, are volunteer keeper coaches with the Bulldogs this season.

But the keeper Flamme looks up to most is former Mason standout Steve Clark, a 2004 graduate who went on to star at Oakland University and currently plays in the top division of Norway’s professional league, Tippeligaen.

Clark made it home for a week this summer, and Flamme worked his way into an hour-long training session with his hero. It was during that brief workout that Flamme picked up on Clark’s attention to detail – something that’s been mostly good but also a little bit frustrating.

Flamme has learned to pay attention to the little things that will help take his game up another level. But he also struggles with dwelling on the smallest of details, which can get in the way of his in-game focus while there are other tasks at hand.

“Keepers, we’re all head cases. We’re all crazy psychos, diving headfirst into balls,” Flamme said. “But at the same time, you’ve gotta be able to forget things.

“I’m just trying to forget the bad things.”

Memories worth saving

Josh’s memories of his dad – like the two kicking the ball around the yard – remain vivid.

Walt was diagnosed during the fall of Josh’s eighth-grade year, but his son didn’t grasp as first the severity of the situation. Not until about three months later, during mid-winter, did Josh begin to understand.

“You could be off with friends, be smiling and laughing, having a good time. But on the inside, you never stop thinking about it,” Flamme said. “On the outside, you’re acting like you’re having fun. Inside it’s just like, ‘This sucks.’ That was always the toughest part – always having in the back of your mind that your parent is just slowly dying.”

Walt Flamme died on April 11, 2010. Still, his dad’s death didn’t hit Josh until a couple days after, when he walked into his father’s room and Walt no longer was there.

The two were inseparable working the family’s 45-acre farm. The Flammes grew soybeans and wheat and had four horses, and Walt knew how to do just about anything needed to keep the gears turning. “He’d do things to his truck I didn’t know there were parts for,” Josh said. “Just by watching, I kinda picked up on stuff. I knew how to do everything.”

Tracy Flamme said they shared the same mellow personality, with Josh now the one who will remind his mom to not get worked up unnecessarily. That “crazy” Josh believes is a key to a keeper’s success? He credits his dad for giving him a dose.

When Walt died, Flamme became familiar with the advice of not remembering the bad times. He had no problems there. Aside from a few spilled glasses of juice, he couldn’t remember his dad yelling at him. “We didn’t have bad times. I couldn’t dream of a better dad,” Flamme said. “I would just think about the positives and just know he’s not going to want me, because he’s gone, to stop working hard in soccer, stop working in school. I want to do what he would want me to do.”

Competing for a Cause

Compete for a Cause began as the brainchild of Gunns, who like Binder is a former Mason soccer player and whose wife, Sheri, has undergone surgeries over the last decade because of thyroid cancer.

Sheri Gunns teaches sixth grade in Okemos, and one of her students two years ago was Paige Duren. Michigan State football fans may be familiar with Duren – she was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 2011 and became an inspirational member of the Spartans’ football family.

Sheri Gunns teaches sixth grade in Okemos, and one of her students two years ago was Paige Duren. Michigan State football fans may be familiar with Duren – she was diagnosed with a brain tumor in 2011 and became an inspirational member of the Spartans’ football family.

Mason’s players also had an unfortunate tie to cancer in classmate Spencer Sowles, a football player who attended last fall’s Compete for a Cause game but died March 18.

Those connections plus that to Walt Flamme made picking a cause for the benefit game easy.

When he and Binder told the team about the event last fall, Flamme thought “this is awesome.” That first game raised $1,000, and with September national pediatric cancer awareness month, Kevin Gunns hopes next week’s match can build on that success.

“Just seeing other families affected by (cancer), I understand what’s going on with them. It’s just cool to help them out in any possible way,” Flamme said. “When my dad was going through it, people would bring over food and stuff like that. For a split second there you feel normal. It’s not a normal situation. Any time we can help families, if we can give them help, have them feel normal for a split second, that’s really cool.”

Back in stride

Flamme has had plenty of mentors off the field as well. Friends’ dads have been there for him, and Binder and Gunns have guided him through his college recruiting questions.

His friends got him back on his feet quickly and have kept him rolling through good times and struggles.

“We’ll have lengthy talks about it every now and then. I think that’s good for us to do,” said sophomore John Kingman, one of Mason’s starting defenders. “It gets it off his mind, helps clear his mind a little bit. I think it brings him to a peaceful time.”

Flamme has committed to play his college soccer at University of Detroit Mercy, and he’s excited about beginning the school’s five-year cyber security program. He hopes to work for the government when college and soccer are done.

“After my husband died, I wanted something good to happen to Josh,” Tracy Flamme said. “And it did.”

Josh has been in net for 55 varsity wins and helped the Bulldogs to Regional Finals each of the last two seasons. There’s nothing he’d like more than to bring home his team’s first MHSAA title since 1997.

If that happens, Flamme will know one of the reasons why.

“I’d have to thank (my dad) for weeks,” Flamme said. “We’ve definitely got the talent. But you’ve gotta be lucky sometimes.

“If he throws a couple balls our way ...”

PHOTOS: (Top) Mason goalkeeper Josh Flamme prepares for an Okemos free kick during the team's 0-0 tie this season. (Middle top) Flamme launches a kick downfield against the Chieftains. (Middle bottom) Flamme also is the placekicker for Mason's football team. (Bottom) At 6-feet tall, Flamme excels at making saves at the top of the goal. (Photos courtesy of Alan Holben.)

'World's Game' Makes Home in Metro Detroit, Then Grows Statewide

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

November 3, 2021

In the fall of 1982, Livonia Stevenson assistant coach Ralph Aulicino suggested to Detroit Free Press stringer Jon Pepper that “somewhere along the Livonia city limits” there should be a sign erected that proclaimed the Detroit suburb as “the state capital of soccer.”

Stevenson’s Spartans had just beaten crosstown rival Livonia Churchill 4-1 in what some called “The Battle of Livonia.” The contest, played at Flint’s Atwood Stadium, was the first-ever Class A Boys Soccer Final sponsored by the Michigan High School Athletic Association.

Guided by head coach Pious (Pete) Scerri, a former first division player in England, Stevenson finished the year with a flawless 22-0 record. Gary Mexicotte scored twice for the Spartans in the title game, finishing with 48 goals on the season. In December, he was named prep All-American.

Aulicino’s statement might have been considered a bit arrogant within the soccer community. Still, there was little question that the surrounding burgs of the Motor City were the hub of the prep soccer world in Michigan at the time.

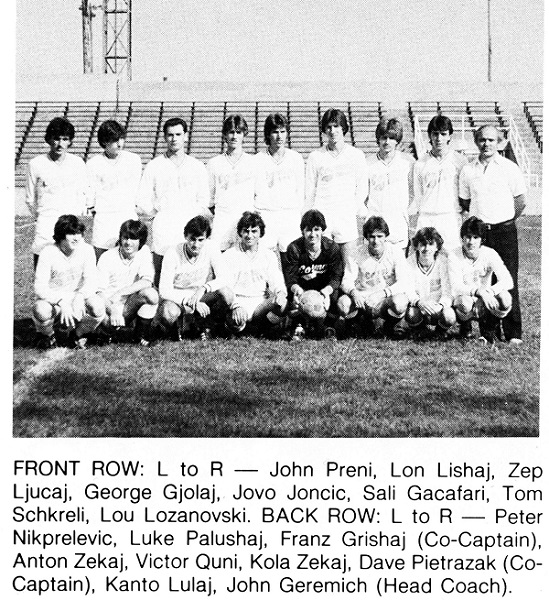

The Hamtramck Cosmos, coached by John Geremich, finished with the MHSAA’s Class B-C honor while Grosse Pointe Woods University Liggett, coached by David Backhurst, earned the Class D trophy in the autumn tournament. The Knights finished the year with an 18-1-1 mark, and would repeat as champs in 1983, but this time in Class B-C.

Dominant

Looking back today, Aulicino’s words were prognostic.

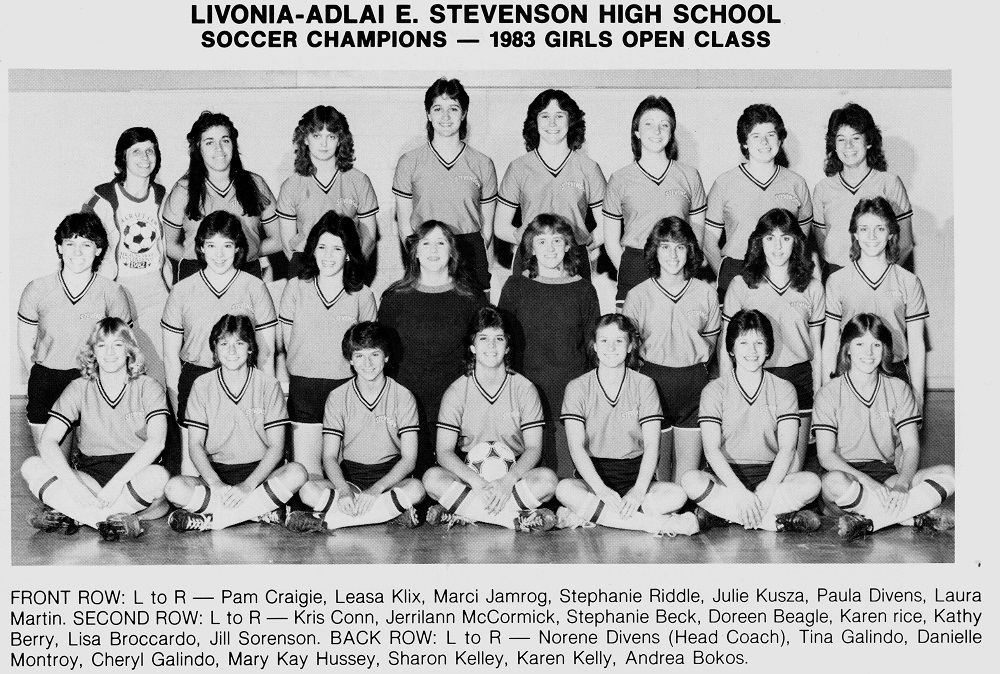

In the spring of 1983, Stevenson’s girls, coached by Norene Divens, grabbed the MHSAA’s first Open Class championship – meaning schools of all sizes competed in one division – with an 8-0 win over Saginaw Eisenhower.

Then Scerri’s boys would appear in an incredible six of the first seven Class A title games, winning four. Divens’ girls appeared in the first three Open championships, winning two while finishing runners-up to Northville in a 5-4 overtime battle in 1984. Churchill’s girls won the 1986 Open title. When the MHSAA expanded the girls postseason to two divisions, Churchill finished runner-up in Class A to Plymouth Salem – yet another metro Detroit high school – in the springs of both 1987 and 1988.

Allen Park Inter-City Baptist won three straight boys Class D titles from 1983 to 1985.

Coach Scerri did emphasize the importance of the moment to the development and changing landscape of sports in Michigan following that first championship:

“Let me put it this way. Usually, we get the rejects from the football team. This year, the football team took three rejects from us. It’s going the other way around now.”

Culinary Delights, Old World Music, and Soccer

The chance to play for an MHSAA Finals title must have been a joyous occasion in the vibrant community of Hamtramck. Geremich, whose team won that first Class B-C championship, explained the city’s connection to the sport in 1980.

“We’ve got a lot of Yugoslavian and Albanian kids who were brought up on soccer,” he told the Free Press. “Their parents never played football and baseball, so they look to soccer.”

“We’ve got a lot of Yugoslavian and Albanian kids who were brought up on soccer,” he told the Free Press. “Their parents never played football and baseball, so they look to soccer.”

Geremich himself was one of those kids. He came to America in 1958 from Serbia and attended Hamtramck. Soccer, however, wasn’t an option at Hamtramck during his days in high school.

Without that outlet, Geremich along with classmates Francisco ‘Pancho’ Castillo from Colombia and Jerry Podesek from Poland, all became standouts in the school’s outstanding tennis program instead. The Cosmos won 11 consecutive MHSAA Class A team tennis state titles from 1949 to 1959, and 18 of 21 between 1949 and 1969. The trio would later attend and play tennis at Southern Illinois University together.

“All three readily admit that soccer and not tennis are the national pastimes in their homelands,” stated the Grand Rapids Press in 1958.

Hamtramck’s top player in 1982 was Kanto Lulaj, who had been playing soccer since the third grade. Only a few years earlier, his family had come to Hamtramck from Albania. A 150-pound junior center-forward, he finished that championship season as Michigan’s most prolific scorer, notching 56 goals. A four-year varsity starter, he was named All-American in 1983, then played collegiately at the University of Connecticut.

Pockets

Delving into the game’s earliest history at the prep level in Michigan certainly helps explain the area’s dominance. Wildly popular among the immigrant population employed in plants across southeastern Michigan, men’s factory and recreational soccer leagues flourished in and around Detroit for years.

The Holley Carburetor F.C. team, sponsored by Detroit’s Holley Brothers Company, gained coast-to-coast attention as it battled to the National Challenge Cup championship game (today known as the Lamar Hunt US Open Cup), played before 10,000 fans at University of Detroit stadium in May 1927. A Detroit professional circuit even came into existence that same year. The short-lived Detroit Cougars, according to the Free Press, were the first incorporated soccer club in Michigan.

“School soccer enjoyed a successful season,” said the Free Press in 1928, “especially in the elementary and intermediate grades, in which more than 17,000 boys participated in the schedule formulated by the health education department of the Detroit public schools.”

Ultimately, the increasing popularity of American football among boys (and spectators) overwhelmed soccer within public school districts, and soccer never became much more than an activity played outside school, or perhaps sometimes during gym class.

Soccer, or at least a form of the game, did appear as an intramural athletic activity in girls gym classes across the state dating back into the 1920s. Occasionally, especially in small towns, contests were played between schools from neighboring districts. For example, Buchanan’s senior girls defeated the sophomore girls from their old rival Niles, 2-0, in 1928.

Soccer, or at least a form of the game, did appear as an intramural athletic activity in girls gym classes across the state dating back into the 1920s. Occasionally, especially in small towns, contests were played between schools from neighboring districts. For example, Buchanan’s senior girls defeated the sophomore girls from their old rival Niles, 2-0, in 1928.

As state and national debate grew concerning the capacity and value of athletic activity and competition amongst girls, the sport was often modified within districts. At Ludington, speedball replaced soccer in 1948-49. At Birmingham Seaholm in 1962, girls participated in speed-o-way, a game similar to soccer that allowed use of the hands.

A Spark

Prep soccer programs found a spark among the boys at select schools in the suburbs of Detroit during the late 1950s and early 60s.

“(Initially) the only people that were playing anything approaching league soccer were the private schools,” recalled John Sala, a former coach at Birmingham Groves.

These programs were started as club sports, representing a school, but generally run outside the finances, guidance, and official sponsorship of a school’s athletic department. Opponents came where they could be found.

School yearbooks from the past help tell the tale.

The sport was played at Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s with games played against other private schools in Canada, Ohio, Illinois, western New York state, and Pennsylvania. Michigan schools first began appearing on the schedule in the 1960s.

The sport was played at Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s with games played against other private schools in Canada, Ohio, Illinois, western New York state, and Pennsylvania. Michigan schools first began appearing on the schedule in the 1960s.

The team at Grosse Pointe University School (GPUS), according to its 1964 annual, “was founded five years ago by Mr. Preston, who returned this year to coach it.” The season was comprised of only six games, played against three opponents – Cranbrook, Bloomfield Hills and a season-ending game with “Preston’s Ringers.”

“With soccer only in its second year as a Varsity sport … the 1965 team showed a promise of successful seasons to come,” read the Bloomfield Hills High School yearbook. The boys finished the year with a 5-3-1 record. “Since soccer has yet to become a league sport,” the Barons faced squads from Cranbrook, GPUS, and Oakland University, as well as teams from Lowe Tech and Sarnia, both from Ontario, Canada.

Soccer became a varsity sport at Detroit Country Day School in 1965. That team finished with a 3-2-3 mark, playing contests with GPUS, Maumee, Ohio, and a newly-formed club team from Groves:

“After a late start in practice because they lacked a coach and equipment, Groves’ first soccer team introduced the rugged game to Birmingham varsity sports. Mr. John Sala took over coaching duties and helped the boys make the transition from last year’s club status to a varsity team with a full season schedule. The arrival of goals and other equipment and the donation of uniforms by Mr. Harrison Tracy boosted team morale and their play improved noticeably.”

“After a late start in practice because they lacked a coach and equipment, Groves’ first soccer team introduced the rugged game to Birmingham varsity sports. Mr. John Sala took over coaching duties and helped the boys make the transition from last year’s club status to a varsity team with a full season schedule. The arrival of goals and other equipment and the donation of uniforms by Mr. Harrison Tracy boosted team morale and their play improved noticeably.”

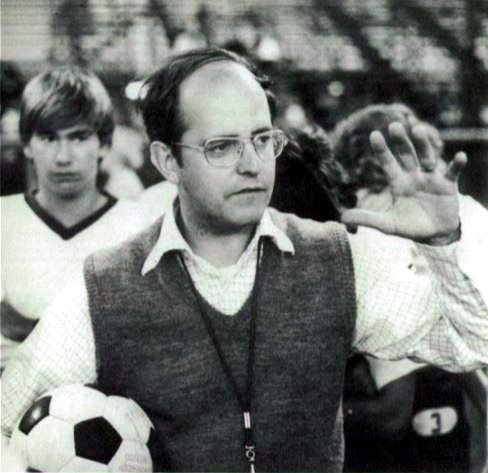

“When I was at Groves and starting out coaching (in 1966), I knew absolutely nothing other than having watched it,” recalled Sala, laughing at the memory. “They had a club team run by another staff member … and he left. Basically, they called me down to the office … I thought I was going to get reprimanded. (Instead) she says, ‘We have to have a coach by 4:00 today.’ I said, ‘How much does it pay?’ She said ‘$300.’ It sounds like a lot of money to me. So, I learned by doing.”

Sponsorship of soccer soon spread to other public schools in the immediate area, with teams appearing at Bloomfield Hills schools Andover and Lahser, the Livonia schools, Birmingham Seaholm, and Ferndale.

West Michigan

On the other side of the state, the soccer seed was taking root in the Greater Grand Rapids area.

“Central Christian, champion of the Christian High School Soccer League, completed its season Saturday morning at Calvin College’s Knollcrest Field by defeating Holland Christian, 3-1,” stated the Grand Rapids Press in October 1966. The four-team league also included Hudsonville Unity Christian and Grand Rapids Calvin Christian.

A year later, Kalamazoo Christian was added to the league, then Muskegon Western Michigan Christian (WMC). Casey Ver Haar, an honorable mention All-American goalie in soccer at Calvin College, coached Central Christian. Dave VerMerris, a former track star at Central Christian, then at Calvin College, took the job at WMC as coach at age 22. He had first given soccer a try as a freshman in college.

“Calvin that year had graduated quite a few of their soccer players,” recalled VerMerris, explaining how that began. “(Several) of their soccer players were immigrants – Dutch immigrants. They were hurting for bodies …”

“Calvin that year had graduated quite a few of their soccer players,” recalled VerMerris, explaining how that began. “(Several) of their soccer players were immigrants – Dutch immigrants. They were hurting for bodies …”

Marv Zuidema, the soccer coach, approached VerMerris sometime in August of 1964 and suggested he give the sport a try.

“I had some speed back in those days, and speed can take care of a lot of things if you don’t have the skill,” said VerMerris, chuckling. “His dream was I would outrun their defense and put the ball in the net. That never happened.”

Sport of the Future

Christian League officials were pleased with the level of competition and attendance at games. Between 100 and 150 spectators were showing up for contests.

“While (the) majority of West Michigan schools compete in nine major sports now,” noted longtime Press sportswriter Joe Vanderhoff in 1968, “it would be a good idea for some of the officials (at other schools) to look into the game of soccer. It’s been the No. 1 sport in Europe for years.”

According to MHSAA surveys, only 12 schools sponsored boys varsity soccer teams during the 1969-70 school year, with somewhere around 300 participants. By the 1975-76 school year, the numbers had grown to 35 schools and 1,085 participants. (Another dozen or so schools had club teams).

Without the numbers needed to meet the threshold for tournament sponsorship set by the MHSAA, the Michigan High School Soccer Coaches Association chose to host a 16-team playoff invitational beginning in the fall of 1975 to name a state champion. Groves, which had played in the 10-team North Woodward Conference, emerged from the knockout brackets to win that first title, defeating Hudsonville Unity Christian, 6-1. According to Free Press coverage at the time, more than 500 attended the championship game.

Undeniably, the sport was exploding in popularity at the participation level with American Youth Soccer Organization (AYSO)-affiliated clubs across the state. A Free Press article had noted that “a soccer team can be outfitted for about one-tenth the cost of a hockey player or one-fifth the cost of a football candidate.”

Still, it would take time. Invitational title tourneys, initially sponsored by the Coaches Association, were continued for six more years. The 1977 open-class single-elimination tournament featured 32 teams, with the state broken into eight regions.

“After a few years, they split it into an ‘A-B’ and ‘C-D’ (classification), recalled VerMerris, who remained at WMC for 30 years. “In 1979, we won the whole shooting match. In 1980, we won ‘C-D’.”

Soccer in Mid and Northern Michigan

Too small to sponsor 11-player football teams, Leland, Northport, Buckley, Lake Leelanau St. Mary, and The Leelanau School in Glen Arbor added soccer to the mix of varsity sports played within the Cherryland Conference in the fall of 1970. Leland’s Comets won the league’s first title that season.

Soccer first hit the Lansing area as a varsity sport beginning in the late 1970s.

“Right now East Lansing High is the only major area school which has included soccer in its interscholastic program,” Lansing Journal correspondent Keith Gave wrote in 1978. “In only its second year, the program brought out 70 students, enough for a varsity team and two junior varsity teams.

“Filling a schedule was a slight problem because few area schools play the game. Holt St. Matthew has had a program for about four years and Lansing Capitol City Christian has one. In fact, up until a few years ago the only soccer to be found at the interscholastic level was in the smaller, parochial schools which didn’t have football programs.

“But,” said East Lansing coach Nick Archer, “it’s just a matter of time before it’ll be all over. The game is just exploding at the youth level.”

Archer, who would coach the Trojans for 41 years, had played soccer at Michigan State and was part of the 1967 and 1968 national champion squads with the Spartans. He had scheduled games with Roeper, Cranbrook, first-year varsity teams from Saginaw Eisenhower and Flint Carman, and with Ann Arbor schools Pioneer and Huron, both in their second year of varsity competition.

Critical Mass Achieved

“In 1974-75, the cheerleaders came to me and said, ‘We want to play soccer,’” recalled Sala. “I had about 85 girls show up so I split them up into four teams – a freshman, sophomore, junior and senior team – an informal thing for the first few years. With Title IX, we already had a club team going – a reliable program.”

Soccer was made a girls varsity sport at Groves during the 1977-78 school year. Girls teams were also active at Livonia and Farmington schools, as well as at Andover, Seaholm, Lahser, and Roeper.

Numbers grew across the state to 71 boys teams and eight girls teams during the 1979-80 school year, then to 84 boys and 36 girls squads a year later.

In December 1980, a committee of superintendents, principals and athletic directors recommended to the MHSAA Representative Council that it sponsor a state soccer tournament for boys and girls beginning with the 1982-83 school year. The Representative Council concurred with the suggestion.

Troy Athens, coached by Tim Storch, one of Sala’s former players at Birmingham Groves, won the last of the A-B invitational soccer championships, played in November 1981. Four of his boys teams and four of his girls teams would later go on to win MHSAA soccer titles. Detroit Country Day won the final C-D Division invitational crown in the spring of 1982.

“More than 45,000 boys and girls in the Detroit metropolitan area – the majority of them in Oakland County – now play in youth soccer programs sponsored by communities, clubs and businesses,” stated Johnette Howard in a Free Press article on the country’s “latest boom sport,” published in September 1982.

“The skill levels of the players are unbelievably improved,” said Bloomfield Hills Lahser coach Chet Schultz. “There is not a boy on my varsity team that hasn’t played at least five or six years.”

Not all coaches were in favor of the move to MHSAA sponsorship.

“Some coaches didn’t like having the MHSAA dictate the number of games to be played, when the season could start, rules for playing Canadian teams, coaching accountability, etc.,” stated VerMerris, who played witness to, then researched and captured detail on those early days of play in West Michigan and across the state.

“The MHSSCA was very instrumental in helping make this a smooth transition and the MHSAA was very willing to work with us. Not surprisingly, not everyone was happy but this legitimized the sport and put it on a par with all the other MHSAA sponsored sports.”

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

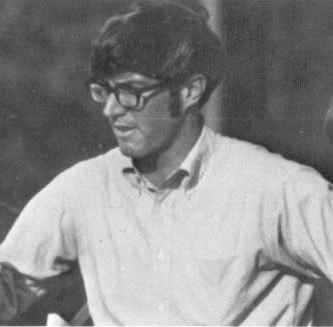

PHOTOS (Top) Livonia Stevenson carries its trophy off the field at Atwood Stadium. (2) Hamtramck was the first Class B-C champion. (3) Birmingham Seaholm students play speed-o-way during the 1962-63 school year. (4) A Bloomfield Hills Cranbrook player possesses the ball during the 1964-65 school year. (5) Birmingham Groves coach John Sala speaks to his team during the 1975 season. (6) Dave VerMerris became the Western Michigan Christian coach at age 22 and led the program for 30 years. (7) Stevenson’s girls won the first MHSAA Open Class championship in 1983. (Photos collected by Ron Pesch.)