Their Place, Forever

February 9, 2012

By Geoff Kimmerly

Second Half editor

It’s surreal, Terry Reid said, humbling and overwhelming every time he sees his name hanging on Marlette’s gymnasium wall.

A little more than a month has passed since the school dedicated one of its most visible buildings to the longtime basketball coach. Thing is, Reid added, those honors usually are bestowed after a person has died – not while he’s still working the sideline, as Reid has done for Raiders teams over the last 40 years.

On the opposite wall hangs a new scoreboard, also dedicated Dec. 28. At the top is the name “Kyle Hall,” one of Reid’s eight grandchildren, a standout player who graduated last spring. Below hangs a photo of number 35, palming a basketball, gazing across the floor where Reid guides his junior varsity team through the same drills he’s been teaching for decades – and where he helped his grandson earn an opportunity to play at the college level.

“Every practice, … there’s a picture of him. And those eyes. I look up, and it kinda chokes me up,” Reid said.

“We’ve been blessed with grandkids who have let you know their feelings for them. ‘Hey Grandpa, see ya, I love ya.’ Those were the last words I heard from him, the day before he died.”

Reid wasn’t sure if he could return to coaching after that day, July 16, when during the early morning hours a car crash claimed Hall’s life as he drove home from a friend’s house.

Reid’s wife of 52 years, Jackie, convinced him to go back – both for himself, and for his grandson. And it seems just right they will be remembered in a place that has meant so much to both.

The plan comes together

Reid, 72, grew up in Redford Township, coached at Redford and then Detroit Benedictine for a short time before moving to Marlette in 1972. He’s coached a variety of teams, including the girls varsity for 21 seasons and the boys for 12 over two tenures, and hundreds of athletes including his daughter and Kyle’s mom Tammi, and currently Kyle’s little brother Dakota.

Kyle Hall got serious  about the game as a junior. At 6-foot-5 and at a Class C school, he was a post player – but realized he’d need better perimeter skills to play after high school. Reid never officially coached Kyle – Hall skipped Reid’s JV team to join the varsity as a sophomore. But that summer before senior year, Grandfather and Grandson got to work, a few hours three days a week, through tough times and good ones that come in part with coaching one’s child, or in this case, grandchild.

about the game as a junior. At 6-foot-5 and at a Class C school, he was a post player – but realized he’d need better perimeter skills to play after high school. Reid never officially coached Kyle – Hall skipped Reid’s JV team to join the varsity as a sophomore. But that summer before senior year, Grandfather and Grandson got to work, a few hours three days a week, through tough times and good ones that come in part with coaching one’s child, or in this case, grandchild.

After earning all-league and all-area honors in his final high school season, Hall was slated to join the Alma College men’s basketball team this fall – in fact, the Scots wear his initials on their pre-game warm-up shirts. Alma College also recently acquired a new scoreboard, and Kyle “told me one time … I’m going to light that sucker up,” Reid remembered.

That was Hall. He’d visit potential colleges with Tammi and his father Mike, and coaches would ask Kyle to list his strong point. Answer: Confidence. Weak point? Same answer. “He went out every game with the plan to win,” she said.

She recalled Kyle’s big feet: “He could run down the floor in three leaps.” Sports were his obvious first love. A three-sport athlete every year of high school, Kyle played football in fall, track and later golf in the spring. Every inch of his bedroom wall was covered either with pictures or clips from newspapers, his workout plan, and the terminology he was learning for nursing. Hall had passed his certification test to work as a nurse assistant two weeks before the crash. He had plans to pursue jobs at the hospitals in Marlette and Alma, and after getting his bachelor’s degree head to University of Michigan or Ferris State University for his master’s in nurse administration.

“When Kyle got something in his head, that’s what he’s going to do,” Tammi Hall said.

‘You just knew that he cared’

Terry Reid is an old-school basketball coach. Fundamentals rule. Defense first. Life has been basketball, golf, and family. He’s Marlette to the core – after all, the dog’s name is Red Raider Reid.

Prior to the gym dedication, the Huron Daily Tribune reported Terry’s various successes: a 315-149 girls varsity record, 100-98 with the boys varsity, and a combined seven District and five league championships. He also led the baseball team to a league title, coached in the football program and was athl etic director for 18 years on top of teaching a variety of subjects.

etic director for 18 years on top of teaching a variety of subjects.

The branches of his coaching tree spread throughout Michigan’s Thumb, and further. Reid estimates at least 40 former players have gone on to run their own teams. Brown City boys basketball coach Tony Burton and Bad Axe girls coach Brent Wehner both played for Reid, as did Kentucky Wesleyan College co-women’s coaches Caleb and Nicole Nieman. Closest to home, former players Chris Storm and his wife Cathy Storm now run Marlette’s boys and girls varsities, respectively.

“You just knew that he cared. … At the time you don’t realize it, but he becomes a true friend shortly after high school and throughout your career,” Chris Storm said.

“You always live through the tough times as well as the good times of teams. He’s been one who has persevered over the years. Everyone certainly goes through it; there are certain teams that don’t accomplish what they should, and that falls on the coach. But he’s always been able to keep his focus on the kids. That’s what we’re here for, and they know it.”

Like any grandparent, Reid takes pride in all of his grandchildren. An athletic bunch, he can recognize basketball potential – even in those who have chosen to play that other winter sport, hockey, instead.

But admittedly, Reid’s relationship with Hall took on another level because of their time together on the court. Storm’s son Alex teamed with Hall in 2010-11 and now plays at Rochester College in Rochester Hills, and Chris Storm recognized the similar tensions to his coaching his son.

But, “there’s certainly no question the time (Reid) spent with him and put in paid off for Kyle,” Storm said. “It was kinda neat they were able to share in that success at the end.”

He will be remembered

Reid said between 30 and 40 people came to the Halls’ home the night Kyle died.

His showing at the funeral home was scheduled to run from 1-9 p.m., but went until 10:20. After a small private funeral, the family went to the gym for a community ceremony – and found it packed.

“I really found out I wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. The support we received at that time, and to the present, has just been unreal,” Reid said. “They stuck with Mike and Tammi, and they still do.”

For the dedication, Kingston agreed to have its varsity girls and boys teams play at Marlette on the same night, instead of the usual JV/varsity doubleheader. Every Kingston player came into the stands and hugged Mike and Tammi. The Raiders boys team has had a bit of a tough one this winter coming off last season’s 17-5 finish – it was just 6-8 heading into Friday – but beat Kingston that night by 20.

In a small town, Storm said, something like Hall’s death brings somberness to the entire community. And, of course, it still hits the family hardest. But Reid is back coaching his junior varsity, with no plans to stop.

And after Dakota is done playing for the JV, Mike and Tammi stick around for the boys varsity games. They watch and support the friends and community that have supported them – and now in the building where they are surrounded by reminders that will continue to live on.

“He was so much fun to watch. I realize he was my own, so obviously I think higher of him. … But it was just so much fun to watch him play,” Tammi said.

“My husband and I talked quite a bit, and that’s where he’ll be remembered, on the basketball court. He packed a lot in those 19 years. ... I think he would think that’s pretty cool.”

PHOTOS courtesy of Reid and Hall families.

TOP: Terry Reid waves to the crowd during the Marlette gym dedication Dec. 28. (Middle) The scoreboard dedicated to Kyle Hall hangs on the eastern wall of the gym. (Right) Hall's retired jersey also hangs at the high school.

MIDDLE (1): A sign honoring Reid and remembering Hall hangs on the western wall of the gym.

MIDDLE (2): Hall (jumping) celebrates his team's outright league championship in 2011. Grandfather Terry Reid is among those pictured behind him.

MIDDLE (3): Reid (left) and Hall posed for a shot during the postgame celebration of that championship win.

BELOW: The full scoreboard, plus a photo of Hall, also were dedicated on Dec. 28.

Before the Bridge: Class E & the UP

July 31, 2017

By Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

This is the final part in a series on MHSAA tournament classification, past and present, that has been published over the last two weeks and originally ran in this spring's edition of MHSAA benchmarks.

The stories are worthy of the silver screen.

Long lost legends of lore, forgotten by most in the Lower Peninsula of the state of Michigan.

Absurd anecdotes of basketball played behind glass, and out-of-bounds lines painted on walls.

Tales of overlooked places like Trenary and Champion and Doelle and Watersmeet.

This is the story of MHSAA Class E basketball.

From 1932 to 1947, Michigan's Upper Peninsula did not compete in the state-sponsored basketball tournament. Instead, the U.P. held a separate basketball tournament, crowning champions in Classes B, C and D. In 1941, the state added a fifth classification – Class E, comprised of schools with a student body numbering 75 or fewer. A fourth bracket was added to the U.P. tourney.

Following the 1948 season, the Upper Peninsula returned to the state tournament. Winners of the traditional U.P. tourney were pronounced regional champions, and advanced to the state quarterfinals in Classes B, C and D. However, since there were no Class E schools with basketball teams in the Lower Peninsula, the winner of the U.P. tournament crown was proclaimed Class E state champion. This arrangement continued through the spring of the 1960 season.

Since they were the state's smallest high schools, the gymnasiums came in all shapes and sizes. Some sported a center circle that intersected with the top of the key. Basketball courts that doubled as a stage required netting to keep the kids and the ball on the court and away from the audience seated below.

Fred Boddy, a former coach at Champion, recalled his first visit to Doelle. Located in copper country near Houghton, the hosts were the proud owners of “the smallest” gym in U.P.

“I couldn't believe my eyes. ... Here on the second floor were windows and bleachers all around filled with fans. The gym, of course, was located on the first floor, but to get into the gym one had to go around to the back of the school to enter through the boiler room to the locker rooms, which opened onto the gym floor much like a dugout on a baseball field. The players sat on a bench under the wall and could look out and see the game in this manner. The free throw lines intersected and there were no out of bounds lines... the wall itself was ‘out of bounds.’ On the floor during the game were 10 players and two referees. There were no sounds as all the fans were up on the second floor, glassed in.

The cheerleaders tried valiantly to fire up the fans up on the second floor, but the teams couldn't hear in the quiet below. The score clock and statistician personnel were placed in a corner box high over the floor in one corner of the gym. They attained this lofty perch by a ladder that was removed from the trap door after all three were in position and the game could thus commence. The timer then tied a rope around his ankle. To send a sub into the game the coach would send the player along the wall heading for this rope. He would pull the rope causing the timer to look down through the trap door and at next opportunity would ring the buzzer and admit this substitute”

Regardless of the challenges presented by these cracker-box gyms, the fans loved their basketball. “The enthusiasm was just the same, if not bigger, than schools twice and 10 times their size,” noted longtime U.P. historian, Jay Soderberg.

Coach Joseph Miheve's 1941 Palmer squad captured the state's first Class E title with a 39-28 win over Hulbert at Ironwood. A graduate of Wakefield High School, Miheve had never played high school basketball, serving as the team's manager.

The 1942 tournament, scheduled for March 19-21, was postponed one week because the city of Marquette was more or less taken over “by nearly 1,000 selective service registrants from every county in the Upper Peninsula” who had another and more serious battle in mind – World War II.

Palmer, this time coached by Elvin Niemi, repeated in Class E with a 37-31 victory over Bergland. It was Palmer's 32nd consecutive victory.

No tournament was held in 1943 due to the involvement of the United States in the war. In the 1944 championship game, Cedarville jumped out to a 19-14 first quarter lead but was held to 24 points in the remaining periods and fell to Amasa, 51-43 at Ishpeming.

Trenary made its lone Class E finals appearance in 1945, losing to Bergland 49-39 at Ishpeming, while the Alpha Mastodons won their first U.P. title since 1934 with a 48-28 win over Champion in 1946. It was the second of five Class E titles for Alpha coach Gerhardt “Gary” Gollakner, one of the finest coaches to come out of the U.P. Gollakner had coached at Amasa two years earlier, and his Mastodons would earn three additional titles during the 19-year run of the Class E championships.

Bergland became the tourney's second two-time winner in 1947, with a 40-37 win over the Perkins Yellowjackets. Perkins made four trips to the Class E finals over the years, including an appearance in the final year of the tournament, but came away empty-handed each time.

The Nahma Arrows made their first appearance in the championship in 1951, losing to Michigamme. Led by coach Harold “Babe” Anderson, a cage star at Northern Michigan College during the early 1940s, the Arrows returned to the finals in 1952. Nahma finished the year with a 21-0 mark and a 64-44 win over Marenisco for the crown.

The two teams met again in a finals rematch the following year. The scored was tied six times, while the lead changed hands seven times in this barnburner. With 15 seconds to play, Nahma led 64-60. Marenisco's Robert Prosser hit a jump shot, then teammate Bill Blodgett stole a pass and scored to knot the game at 64. With two seconds remaining, Nahma's Bernard Newhouse was fouled. Newhouse hit the first free throw, but missed on the second. Teammate Wendell Roddy tipped in the rebound, and the Arrows had their second title.

The two teams met again in a finals rematch the following year. The scored was tied six times, while the lead changed hands seven times in this barnburner. With 15 seconds to play, Nahma led 64-60. Marenisco's Robert Prosser hit a jump shot, then teammate Bill Blodgett stole a pass and scored to knot the game at 64. With two seconds remaining, Nahma's Bernard Newhouse was fouled. Newhouse hit the first free throw, but missed on the second. Teammate Wendell Roddy tipped in the rebound, and the Arrows had their second title.

Alpha returned to the championship circle in 1954 with a 52-48 win over Perkins.

The 1955 title game matched a pair of the finest teams in Class E history. Trout Creek, making its first championship appearance, downed Alpha 84-83 in another Class E thriller. Don Mackey led the winners with 39 points. Tony Hoholek paced Alpha with 31, while junior John Kocinski added 21-points for the Mastodons.

Kocinski, a four-year starter at Alpha, scored 1,782 points during his career, then an all-time U.P. record. He once scored 51 points against Amasa, and could have scored more according to teammate Walter “Slip” Ball. “He refused to shoot in the fourth quarter, and passed up one shot after another,” Ball said.

Without question, Trout Creek was one of the powerhouse squads during the final years of the tourney. The Anglers, coached by Bruce “Pinky” Warren, a former captain of Purdue's football team, made four trips to the finals during the last six years of the Class E tourney. The defending champions downed Alpha in the semifinals of the 1956 tournament, then knocked off Hermansville 86-68 in the finals to repeat. It was a year of celebration for fans of U.P. basketball, as four of the state's five champions – Stephenson (B), Crystal Falls (C), Chassell (D) and Trout Creek (E) – came from Michigan's northern peninsula.

Hermansville returned to the finals in the spring of 1957 and earned its second Class E title with a 77-51 win over Michigamme at Escanaba. Trout Creek downed Perkins 61-41 for their third crown in 1958.

The 1959 championship, hosted at Northern Michigan College's fieldhouse, was a showdown of the U.P.’s only undefeated squads, Trout Creek and Nahma. Trout Creek was riding a 24-game winning streak that dated back to the 1958 season. A scoring machine, Warren's Anglers averaged 81.7 points per contest. Nahma, 19-0 on the season, boasted the U.P.'s strongest defense. Still coached by “Babe” Anderson, the Arrows had allowed an average of 38.2 points per game. Led by senior Warren Groleau, Nahma had been last defeated by Trout Creek in the semifinals of the 1958 tourney.

Leading 25-15 at the intermission, Nahma matched Trout Creek point for point in the second half for a 55-45 victory.

Hermansville, behind Richard Polazzo's 29 points and Irwin Scholtz's 27, downed surprise finalist Perkins 72-50 in the 1960 finale, to end this chapter in MHSAA history.

Today, most of the former Class E high schools are long gone. Many have closed their doors and consolidated with other area schools. Amasa and Alpha merged with Crystal Falls to form Forest Park. Palmer is now part of the Negaunee school system. Bergland and Trout Creek joined forces with Class D Ewen to form Ewen-Trout Creek. Hermansville combined with Powers to form North Central, to name but a few. A few remain: Dollar Bay, Marenisco (now Wakefield-Marenisco) and Watersmeet, and their enrollments are much the same as in the glory days of the state's fifth classification.

Author’s note: Special thanks to Jay Soderberg and Roger Finlan, who assisted in gathering statistics and quotes used in this article. Thanks also to Dick Kishpaugh, Bob Whitens, Walter “Slip” Ball, Dennis Grall, Fred Boddy, Bruce Warren, Gene Maki, Harold “Babe” Anderson and the various personnel at U.P. high schools for their contributions to this story.

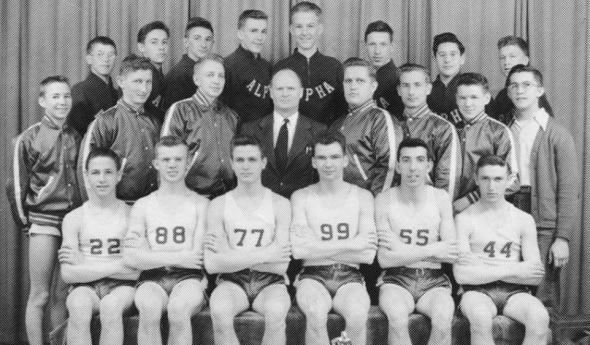

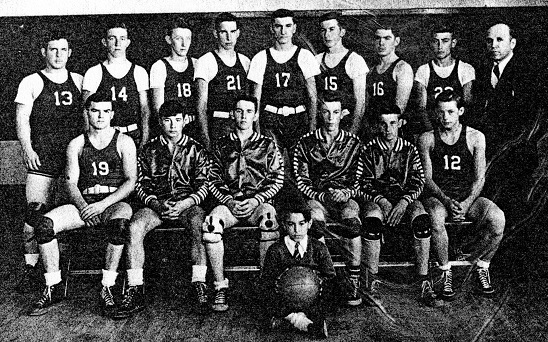

PHOTOS: (Top) The Alpha boys basketball team won the 1950 Class E title by nearly doubling up Michigamme, 52-28. (Middle) Hermansville claimed the 1948 title with a 58-38 win over Rockland.