As Soules Guided, East Catholic Reigned

January 31, 2019

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

“I’m surprised to be this far. Some nights we play very good and some nights we play very bad. I just didn’t think we’d be consistent enough to get this far.”

The words were spoken by varsity basketball coach Dave Soules of Detroit East Catholic back in 1973, but, no doubt, could have come from any number of coaches who have found themselves, unexpectedly, somewhere deep into the MHSAA postseason.

It was Soules’ first season in charge of Detroit East Catholic’s varsity, but far from his first year in the building the school occupied.

The Chargers had advanced to the Class B Quarterfinals the previous year, falling to perennial powerhouse River Rouge, 65-64. That East Catholic team was coached by Eugene Dennis Alexander. An all-city player at Detroit Northeastern, Denny Alexander played college ball at Aquinas in Grand Rapids and became only the fourth player in Michigan collegiate history to surpass 2,000 points in a career, joining John Bradley of Lawrence Tech, Dave DeBusschere of the University of Detroit and the University of Michigan’s Cazzie Russell on the list. In May of 1969, at age 23, he was named head coach at East Catholic.

Denny’s brother, Darryl Alexander, was East Catholic’s best ballplayer in 1972. The team streaked to 11 straight victories during the regular season, then squared off in a series of late February games against larger Detroit Public School League teams. The scheduling was designed to ready the squad for the postseason. Losses to Detroit Southeastern (68-47), Detroit Kettering (80-71) and Detroit Northern (59-58) were a means to that end. While the Chargers did not make the Detroit Catholic League tournament, they were ready to do some damage in the Class B MHSAA tournament.

Denny’s brother, Darryl Alexander, was East Catholic’s best ballplayer in 1972. The team streaked to 11 straight victories during the regular season, then squared off in a series of late February games against larger Detroit Public School League teams. The scheduling was designed to ready the squad for the postseason. Losses to Detroit Southeastern (68-47), Detroit Kettering (80-71) and Detroit Northern (59-58) were a means to that end. While the Chargers did not make the Detroit Catholic League tournament, they were ready to do some damage in the Class B MHSAA tournament.

Only a field goal by River Rouge’s Byron Wilson with 26 seconds remaining prevented the Chargers from doing more. East Catholic trailed in the Quarterfinal by as many as 14 points, and made valiant runs to pull within a point on two occasions, but couldn’t upset coach Lofton Greene’s Panthers. Alexander finished with 19 to again lead the Chargers but was lost to fouls with 1:37 remaining in the third period. Trailing 61-53, East Catholic cut it to 61-60 with 1:35 left to play on a Phil Young field goal. Larry Merchant’s pair of free throws again brought the margin to a single point, 65-64 – but with only five seconds left, the Chargers were out of miracles.

River Rouge, on the other hand, was not. The Panthers would advance through the Semifinals and then survive another thriller, escaping with another one-point victory in the title game against Muskegon Heights. That win marked their 12th Class B title in 19 years.

The Chargers finished the season with a 16-7 record. Alexander earned Associated Press Class B all-state honors that season as a senior, averaging 20 points, 13 rebounds and six assists per game. Come the fall, the brothers headed north to Central Michigan University, where Darryl became a prized recruit. In mid-September, CMU president William Boyd announced Denny had been hired as an assistant coach.

In 1977, Denny was interviewed for the head coaching vacancy at Wayne State, and then was named head coach at Xavier University in New Orleans in 1978.

In 1966, with shrinking enrollments driven by flight of parishioners to the suburbs and rapidly changing neighborhood demographics, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Detroit directed that four Catholic high schools on Detroit’s east side – St. Catherine, St. Rose, Annunciation, and St. Charles – consolidate into the old St. Catherine building at 4130 Maxwell Street.

The amalgamation was christened Detroit East Catholic, and it opened its doors in the fall of 1967.

But the mergers were simply not enough. Needs for new equipment, combined with increased costs for teacher salaries and legislative changes to funding meant a need to increase tuition to cover expenses. That, in turn, led to even more departures.

“The East Side Catholic schools ran up a total deficit of over $1 million last year,” said Bishop Thomas J. Gumbleton, vicar general of the archdiocese, announcing additional closings and mergers of high schools and elementary schools planned with the conclusion of the 1968-69 school year.

“The East Side Catholic schools ran up a total deficit of over $1 million last year,” said Bishop Thomas J. Gumbleton, vicar general of the archdiocese, announcing additional closings and mergers of high schools and elementary schools planned with the conclusion of the 1968-69 school year.

Detroit St. Anthony and Detroit Elizabeth were merged into East Catholic to help address the deficit and exodus. With the changes in the fall of 1969, East Catholic High School was relocated from St. Catherine’s to the St. Anthony building a mile away at the corner of Field and Frederick streets.

Soules had graduated from Dearborn Sacred Heart in 1957 and then the University of Detroit. He was hired as an English teacher at St. Anthony and became the school’s JV basketball coach in 1962. In 1964, he took charge of the varsity team.

“When we merged (into East Catholic) they divvied up the jobs and Dennis got the basketball job,” said Soules in 2005 to Mick McCabe, Detroit Free Press sportswriter. “If I’d have got the job, I’d have lost my mind. I mean literally. The merger was painful. Everybody hated everybody else …”

In May 1972, the Free Press had interviewed Soules about the challenges and the future of the school located at 5206 Field. As an assistant principal, he spoke for those who remained.

“From here, there isn’t any place to go. You close up, and you go out of business. If we keep working at it and keep believing in it, it’s gonna keep going. It has so far. If we close, there’s no inner city Catholic school on the lower east side,” he said.

Raffles, paper drives, lollipop and baked good sales, car washes, fish dinners and dances all contributed to keeping the doors open.

Making a new school community from all of the former had not come easily.

“It was hell. I lost 25 pounds last year. We lost a lot of good staff people. But we came back this year, and, all of a sudden, people could smile at each other in the halls. That’s important. As people got to know each other, they did become friends,” Soules added

With Alexander’s late departure, Soules became the school’s newest varsity basketball coach. At the time, no one knew that he would also be the school’s last.

With the graduation of Darryl Alexander, the expectations of the team, loaded with juniors and sophomores, were limited. Smaller enrollment meant the team had fallen a classification come tournament time. With a 5-3 mark, the Chargers were No. 5 in Hal Schram’s weekly Free Press Class C Top Ten in early January, but had fallen well out of the United Press International’s Top 20 Class C rankings by mid-February with a 12-4 record. The team was quickly eliminated in the annual Detroit Catholic League tournament and, unranked in the final state polls, carried a 12-6 record into the MHSAA postseason. Following District wins over Hamtramck St. Florian – ranked eighth by AP – and Hamtramck St. Ladislaus, Soule’s crew quickly changed the landscape in the opening round of the Class C Regionals.

“Just two days into regional play, the tourney is starting to live up to its Pseudonym – ‘March Madness’”, wrote Harry Atkins for The Associated Press.

“Just two days into regional play, the tourney is starting to live up to its Pseudonym – ‘March Madness’”, wrote Harry Atkins for The Associated Press.

“The Chargers were given hardly a chance against a talent-rich Dearborn St. Alphonsus team in Class C action,” continued Atkins, “but East Catholic didn’t let Dearborn’s No. 2 ranking scare them as they matched the Arrows basket for basket.” Trailing by six with 1:46 left to play, Larry Merchant’s field goal with 46 seconds left tied the score. “Then Mike Walton hit a free throw with one second on the clock to give East Catholic its upset.”

Mike Woods led the team with 21 points. St. Alphonsus exited the tournament with a 22-2 mark.

On a very snowy evening across Michigan, East Catholic took advantage of its height and survived a 27-point performance by New Haven’s Don Sims to win their Regional and advance to the Quarterfinals of the MHSAA tournament. Merchant scored 10 of the Chargers’ 11 points in the final four minutes to seal the 68-63 win.

Merchant showed off his ball-handling skills dishing out 12 assists in the 71-48 Quarterfinal win over Erie-Mason. Sophomores Greg Guye, a 6-foot-6 center, and Walton, a 6-2 sophomore guard, each pumped in seven field goals, both finishing with 14 points, to lead the Chargers in scoring.

Merchant scored 26, while Walton added 23 – 18 points over his season average – as East Catholic rolled to a 66-55 Semifinal victory over Battle Creek St. Philip to earn a trip to the championship game.

“We had accurate scouting reports on East Catholic,” said St. Philip coach Tom Miller following the game. “They were quick. I knew we were in trouble when we had a fast break – and they had two guys at the other end waiting for us,” Miller told UPI’s Richard Shook, laughing. “At least we got beat by a team that was better than we were.”

The state’s scribes had a week to contemplate the upcoming Final matchups as Michigan’s tournament format of the time injected seven days between the Semifinal and Final rounds. Soules had never won a tournament game as a coach at St. Anthony, and noted his club’s strengths and challenges to the media during the time.

“This is a young team which makes mistakes,” he told Atkins of the AP, “but we don’t quit and we’ve won some games on hustle in the last few minutes. It is difficult to key on one player and beat us, because we have excellent balance.”

In a conversation with Schram he noted that his team had a tendency to work out big leads, then start to get sloppy.

“We’ve never put anyone away yet,” he added. Schram noted that Soules took only half of the 700 tickets allotted East Catholic at the state association. “I won’t sell all that I have. These kids simply don’t have the bread to go running all over the state.”

“I don’t believe many of our students or fans have a great amount of confidence in us,” declared the coach, but emphasized that was not the view of the team. “They want this state title and will fight all the way to win it Saturday.”

By most, if not all accounts, not many others had faith in the Chargers’ chances in the championship matchup.

“St. Stephen lost in the ‘C’ finals in 1972 to Shelby and have their key players returning,” wrote Fred Stabley Jr. in the Lansing State Journal. “Led by 6-5 Elijah Coates and 6-2 Jimmy Beavers, St. Stephen has the size and speed to win it all this year.”

“Every game is a home game for Saginaw St. Stephens,” noted Atkins in his pregame AP write-up. “The Titans have a frenzied following of nearly 1,500 fans at every tournament game and you can bet your last lottery ticket they’ll all be in Ann Arbor for Saturday’s showdown.

“On paper there’s no way you can pick a favorite … but neither St. Stephens nor East Catholic has been winning on paper … Saginaw, however, has done a slightly better job of it and who can measure how much their loyal throng of well-wishers has contributed to that record.”

“On paper there’s no way you can pick a favorite … but neither St. Stephens nor East Catholic has been winning on paper … Saginaw, however, has done a slightly better job of it and who can measure how much their loyal throng of well-wishers has contributed to that record.”

“East Catholic won’t make the trip to Ann Arbor for nothing,” wrote Schram, as his alter ego, “The Swami,” on the Saturday of the game. “There’s a trophy for the runnerup.”

Saginaw coach Sam Franz, celebrating his 25th year as a coach, may have been the only skeptic.

“Any team that comes this far has to have something more than luck going for them,” said Franz to Schram.

The story of the Final can still be seen in silence today.

“From the late 1940’s to the mid 1970’s the Michigan High School Athletic Association shot portions of the action at its basketball finals on 16mm film,” notes John Johnson, communications director for the MHSAA. “Some of the films only have portions of the second half and the postgame awards; some have most of the action. None of the films have sound.”

One of the surviving films is the 1973 Class C classic. The Chargers blew a 10-point lead late in the third quarter. With 2:29 remaining, the game was tied, 46-46. A free throw gave St. Stephen the lead 47-46 with 2:16 to play.

The final two minutes of film spools out the story, in thrilling – and heartbreaking – detail.

In the days before the possession arrow, jumps for possession could mean the difference between victory and defeat. East Catholic won a possession on a jump ball, but a miss by the Chargers and a defensive rebound by St. Stephen sent the Titans into stall mode. However, a turnover grabbed and converted by Merchant gave the Chargers a 48-47 lead with just over a minute to play.

A pair of free throws by Elijah Coates pushed St. Stephen out front 49-48 with 45 seconds left. Yet with four seconds remaining on the clock, Merchant's 18-foot jumper from left of the key gave the Chargers a 50-49 victory.

The front page of the Free Press shouted the headline, “A Chance to Be Somebody,” with a story representative of the time. Focused on the players and their struggles, the title could have easily applied to the re-start of a coaching career, and a life, which ultimately would become legendary at least on Detroit’s east side.

To students, he became famous for a rope of keys around his neck, his pad of detention slips and the substitution of “Hot Dog” or “Baby” for names when trying to keep the halls clear during the school week. Saturday mornings for many included time in “The Jug” serving detention.

To students, he became famous for a rope of keys around his neck, his pad of detention slips and the substitution of “Hot Dog” or “Baby” for names when trying to keep the halls clear during the school week. Saturday mornings for many included time in “The Jug” serving detention.

“He’s more to East Catholic than just the basketball coach,” Lou Miramonti told Jo-Ann Barnas of the Free Press in 1996. Miramonti, the athletic director at Royal Oak Shrine, knew of whom he spoke. “It’s the most visible thing he does, but it may well be the least important thing that he does at that school and for those kids.”

Soules was assistant principal, disciplinarian, tuition collector, the giver of rides, and one who called students just to make sure homework was getting done. And, of course, the coach that guided the talent that came through the halls of a building that today no longer stands.

Playing witness in 2005 to another sweeping closure of schools by the Detroit archdiocese – one that included the shuttering of East Catholic – Soules discussed a career he never could have predicted.

“I was the right guy who just happened to be in the right place at the right time,” he explained to McCabe as he tried to come to grips with the announced closing. Soules’ coaching career at East Catholic featured 544 wins against 250 defeats over 33 seasons. The Chargers’ athletic cases included eight MHSAA Finals championship trophies won by his teams. To this day, only Greene at River Rouge won more.

An honest, humble and caring individual with a “self-deprecating sense of humor,” he discussed those earliest of days:

“The saddest part is, I was so dumb at the time, we didn’t win it again (over the next two years) … I didn’t know how to deal with the 2-2-1 three-quarter court press (in 1974) … in the semis (in 1975) … we just weren’t ready to play.”

“With some of the kids I had, you didn’t have to be a genius,” he stated. “I’m a lot better coach now than I was then.”

In 2009, Soules passed away after a three-year battle with cancer. His extended family numbered thousands.

The many condolences that followed, and that continue today, are a heartfelt testament to the difference one man can make in a life, both on the court and in the hallways, of an ancient building built with the lofty purpose of education.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

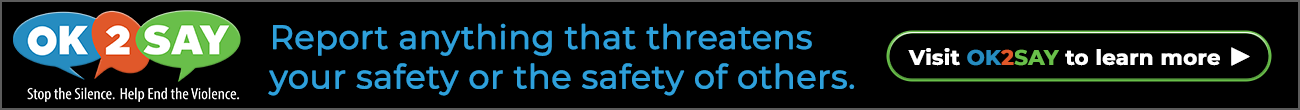

PHOTOS: (Top) The Detroit East Catholic 1973 Class C championship team. (2) Denny Alexander was hired as East Catholic boys basketball coach in 1969. (3) The former Detroit St. Anthony High School. (4) Dave Soules coaches his East Catholic players during the 1973 season. (5) Film survives from the Chargers’ 1973 championship game win over Saginaw St. Stephen. (6) Soules instructs his team during a 1996 game. (7) The Detroit East Catholic gymnasium, after the school’s closure. (Photos gathered by Ron Pesch.)

MCC's Glover Fills Key Role as Athletic Trainer for Super Bowl Champions

By

Tom Kendra

Special for MHSAA.com

August 6, 2024

David Glover never had the glamour role – and didn’t even play the glamour sport – during his high school days at Muskegon Catholic Central.

MCC is known statewide as a football powerhouse that ranks third in state history with 12 MHSAA Finals championships during the playoff era. But basketball was Glover’s sport of choice, and his specialty didn’t show up in the box score.

MCC is known statewide as a football powerhouse that ranks third in state history with 12 MHSAA Finals championships during the playoff era. But basketball was Glover’s sport of choice, and his specialty didn’t show up in the box score.

“I was the defensive stopper,” explained Glover, who graduated from MCC in 1996. “I was always the guy that Coach (Greg) Earnest would put on the other team’s best scorer. I took a lot of pride in that.”

Glover continues to be the ultimate team player, only now his role is the first assistant athletic trainer for the Kansas City Chiefs, who are aiming to three-peat this season as Super Bowl champions.

“As the team and the goals have grown, so have I,” said Glover, who has been on the Chiefs’ training staff for the past 18 years. “The job is the same, which is getting the players onto the field and back onto the field after injuries so that they can perform at their highest level. I have become more comfortable and experienced in that role.”

Glover broke into the NFL as an athletic training intern with the New York Jets in 2004. He came to Kansas City in 2006 when Jets head coach Herman Edwards took the KC job, bringing Glover and several other members of the training staff with him.

Glover quickly fell in love with the Chiefs’ famous family-first culture, along with the area’s world-famous barbecues. He also met his future wife, Jera.

He is known as a tireless worker and student of his craft, which has allowed him to steadily move up to his current position as first assistant athletic trainer on the Chiefs’ five-member training staff, second only to Rick Burkholder, the vice president of sports medicine and performance.

Glover’s skills also have caught the attention of his colleagues across the NFL, who awarded him the 2022 Tim Davey AFC Assistant Athletic Trainer of the Year Award – given annually to someone who represents an unyielding commitment, dedication and integrity in the profession of athletic training.

Glover said a big reason for his success in his profession can be traced back to high school.

“Playing sports at MCC, especially for a smaller school, gave me such a sense of camaraderie, teamwork and a family outside of my normal family,” said Glover, the son of David and Lyndah Glover. “Those teammates energized me to be my best.

“Playing sports at MCC, especially for a smaller school, gave me such a sense of camaraderie, teamwork and a family outside of my normal family,” said Glover, the son of David and Lyndah Glover. “Those teammates energized me to be my best.

“There’s no doubt that some of the lessons that I learned playing sports in high school help me out in my job.”

Glover also ran track for the Crusaders – competing in the long jump, 200 meters, 400 meters and various relays – and said he enjoyed himself, even though he ran track initially as a way to stay in shape for basketball.

The highlight of his MCC basketball career came his senior year, when the underdog Crusaders captured a Class C District championship.

Growing up in Muskegon and close to Lake Michigan, Glover thought he would become a marine biologist someday – that is, until he suffered an injury during his senior basketball season.

Glover went up for a block and actually pinned the opponent’s shot against the backboard. However, the shooter inadvertently took his legs out on the play, causing him to crash violently to the court and lose feeling in his right leg for about 10 seconds.

The injury to his hip flexor put him on crutches for two weeks and off the court total for about a month, which he said “felt like the end of the world” at the time.

But the injury led him into rehab with Brian Hanks, a 1988 MCC graduate who was back working at his alma mater as an athletic trainer through Mercy Hospital.

Glover and Hanks turned out to be a perfect match. Glover was naturally curious about the entire process and wanted to know the “why” of his rebab program. Hanks recognized Glover’s interest in how the human body works and encouraged him to consider studying athletic training in college.

“God works in mysterious ways,” said Glover. “I was devastated when I got injured, but that experience opened my eyes to a whole new career. I wanted to learn everything I could about the human body and how it works.

“Looking back, the injury was a blessing in disguise. I wouldn’t change anything at all.”

Glover followed in Hanks’ footsteps and attended Central Michigan University, spending countless hours in the training room working with athletes in every sport – from football to track to gymnastics – graduating with a degree in health fitness and exercise science.

He said a huge inspiration in his career was CMU professor Dr. Rene Shingles, who in 2018 became the first African-American woman to be inducted into the National Athletic Trainers Association Hall of Fame. Shingles encouraged Glover to continue his studies at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, where he earned his master’s of science in athletic training.

He got his break into the NFL with his internship with the Jets, and his work ethic has kept him there for the past 20 years.

“If there are high school kids out there reading this, I guess I would tell them that there are a lot of different avenues to get to the NFL or the NBA,” Glover said. “I’m a perfect example. I didn’t even play high school football, but through athletic training I have been part of three Super Bowls.”

“If there are high school kids out there reading this, I guess I would tell them that there are a lot of different avenues to get to the NFL or the NBA,” Glover said. “I’m a perfect example. I didn’t even play high school football, but through athletic training I have been part of three Super Bowls.”

The Chiefs, who won their first Super Bowl way back in 1970, would have to wait 50 years (until 2020) to win their next one. But Kansas City now has won three Super Bowls in five years, adding titles in 2023 and 2024.

“To have these kind of experiences, and to be able to share so much of it with my family, is really a dream come true,” said Glover, 45, who said his ultimate goal is to become the head athletic trainer for an NFL team.

“I am always open to see what opportunities God has for me and what doors he opens.”

More immediately, with the start of training camp last month, Glover is back to his seven-day-a-week schedule, sharing the organization’s goal of making it to the Super Bowl for the third consecutive season.

Glover has worked with all of the Chiefs star players at some point, including star quarterback Patrick Mahomes, who he calls “a great, humble man.”

But perhaps the player he has worked with most is standout tight end Travis Kelce.

Kelce, who has become a huge name outside of football as the boyfriend of pop sensation Taylor Swift, injured his knee during his rookie preseason in 2013, sidelining him for the entire year. Glover was assigned to Kelce for his rehab.

With Glover’s daily help, Kelce was able to get back on the field the following year and emerged as a star, earning him the 2014 NFL Ed Block Courage Award as a model of inspiration, sportsmanship and courage.

After winning the award, Kelce invited Glover (he calls him “DG”) and his wife to attend the award ceremony with him in Baltimore.

“That was a huge honor for me, and I was blown away,” said Glover. “I look at it that I was just doing my job. He entrusted and believed in me throughout the process, and it worked out great.”

2024 Made In Michigan

August 1: Lessons from Multi-Sport Experience Guide Person in Leading New Team - Read

July 30: After Successful 'Sequel,' Suttons Bay's Hursey Embarking on Next Chapter - Read

July 24: East Kentwood Run Part of Memorable Start on Knuble's Way to NHL, Olympics - Read

July 22: Monroe High Memories Remain Rich for Michigan's 1987 Mr. Baseball - Read

July 17: Record-Setting Viney Gained Lifelong Confidence at Marine City - Read

July 11: High School 'Hoop Squad' Close to Heart as Hughes Continues Coaching Climb - Read

July 10: Nightingale Embarking on 1st Season as College Football Head Coach - Read

June 28: E-TC's Witt Bulldozing Path from Small Town to Football's Biggest Stage - Read

PHOTOS (Top) At left, David Glover as a senor during the 1995-96 school year at Muskegon Catholic Central, and at right Glover shows the AFC Championship trophy after Kansas City's 17-10 win at Baltimore on Jan. 28. (Middle) Glover, left, hugs teammate Doug Dozier after a victory over rival Muskegon Mona Shores in 1995-1996 basketball season opener. MCC finished 17-7 and a District champion. (Below) Glover poses with this year's Super Bowl Championship trophy alongside fellow Chiefs athletic trainer Julie Frymyer. (Trophy photos courtesy of David Glover; 1996 photos courtesy of the MCC yearbook.)