Detroit 'Longtime' Boys Coaches Down to Few

By

Tom Markowski

Special for Second Half

December 14, 2016

Gary Fralick considers himself one of the fortunate ones.

Fralick, 66, is in his 32nd season as a head boys basketball coach. He retired from his teaching position in 2013. He started coaching at Redford Thurston in 1979, went to Royal Oak Kimball in 1984 and is in 23rd season as the head coach at Troy.

Fralick, 66, is in his 32nd season as a head boys basketball coach. He retired from his teaching position in 2013. He started coaching at Redford Thurston in 1979, went to Royal Oak Kimball in 1984 and is in 23rd season as the head coach at Troy.

Fralick might be lucky, but he is unquestionably rare. Fralick is believed to be one of three coaches in the Macomb/Oakland/Wayne area who has coached for more than 30 seasons.

There’s Dan Fife at Clarkston and Kevin Voss of Clinton Township Chippewa Valley, both of whom in their 35th seasons, all at the same school.

Another, Greg Esler at Warren DeLaSalle, is in his 30th season. He was the head coach at St. Clair Shores Lake Shore for seven seasons before going to DeLaSalle in 1994.

“We’re part of a dying breed,” Voss said.

It certainly appears so. Coaching longevity has taken on a different meaning recently. Twenty seems like a lot in these times, and in reality it is a long time. Twenty years or so ago, 20 years was normal. There’s a new normal, and 20 or 25 years isn’t it.

Many factors have contributed to this change. A person’s personal and family life often don’t coincide with the demands of coaching basketball. The responsibilities that come with coaching have increased. Some coaches say that to be an effective coach, it can be a 10- or 11-month job.

Two factors are at the forefront, and they are both financial. Coaches used to be educators as well as coaches. Yes, coaching can be viewed as teaching on the court, but at one time teaching in a classroom and coaching used to go hand in hand.

Then there’s the subsidy coaches receive. It varies from school district to school district. Some make $4,000 a season, others can make $7,000. And it also costs money to run a program; unless the coach receives financial help from a booster club or parents, the money he or she receives begins to dwindle.

Then there’s the subsidy coaches receive. It varies from school district to school district. Some make $4,000 a season, others can make $7,000. And it also costs money to run a program; unless the coach receives financial help from a booster club or parents, the money he or she receives begins to dwindle.

But the most important factor is time.

“A tremendous amount of time is devoted to watching DVD or tapes,” Fralick said. “I know I’m dating myself with saying that. The point is, you’re watching a lot. There’s more scouting. And you don’t get paid much. Why don’t they stay as long as they used to? They get burned out. They want to spend more time with their families.

“You don’t see as many of the young coaches stay. Coaches don’t have the ambition to coach a long time. It’s not a profitable job. I don’t know what other coaches make. We used to compare what we made. Not anymore.

“Thirty years or more? I don’t see it happening. There’s the dual job thing. Things have changed. To me, it’s been a great job.”

To compensate for being away from home, Fralick brought his family with him. Sort of. He coached his son Gary, Jr., and Tim. Gary, a 1996 Troy graduate, played for his father his junior and senior seasons and Tim, a 1999 graduate, played four seasons on varsity. Fralick said he was even more fortunate to coach both on the same team (during the 1995-96 season).

Then there’s his wife, Sharon, who remains the scorekeeper.

“I’ve always had a passion for coaching and teaching,” Fralick said. “I love the game of basketball. I love the kids. There’s never a dull moment. It’s been a great ride.”

Vito Jordan has been around basketball all of his life. His father, Venias Jordan, was the boys head varsity coach at Detroit Mackenzie and Detroit Mumford before stepping down as a head coach only to return to the bench assisting his son the last six seasons.

Vito Jordan, 31, became a head coach at Detroit Osborn when he was 24. He started his coaching career the year before as an assistant to Henry Washington at Macomb College. Jordan went to Detroit Community after one season at Osborn and guided Community to its only MHSAA Finals appearance (Class B, 2013). He’s now in his fourth season as the head coach at Detroit Renaissance.

“I followed my father all of my life,” Jordan said. “I knew what I wanted to do when I was in college (Alma College). This is what I want to do the rest of my life.”

It’s different in Detroit. Schools close. Job titles change. Jordan, for instance, teaches at the Academy of Warren, a middle school in Detroit. It’s a charter school, not within the Detroit Public School system, therefore he receives his pay from two separate school systems (Renaissance is in the DPS).

There is a distinction. In some school systems coaches will receive a percentage – let’s say for argument sake, 10 percent – of their teaching salary to coach. Let’s say a person makes $60,000 a year to teach. He or she would then receive $6,000 to coach. If you coach two sports, that’s $12,000.

Jordan is not privy to such a contract. Each job is separate. Jordan loves to coach, and he understands he must be a teacher to earn a decent living, and he’s content to continue on the path he is following. But he also knows that to make a good salary just coaching one must move on to the collegiate level like others have done.

Jordan is not privy to such a contract. Each job is separate. Jordan loves to coach, and he understands he must be a teacher to earn a decent living, and he’s content to continue on the path he is following. But he also knows that to make a good salary just coaching one must move on to the collegiate level like others have done.

“When there were coaches like my dad, Perry Watson (Detroit Southwestern), Johnny Goston (Detroit Pershing) and others, they all worked in the (Detroit Public) school system. Everyone was teaching. That was your career. None of them had aspirations of being a college coach. Not even Watson. Now everyone isn’t in the teaching profession. Maybe they do have a degree and maybe they don’t. The point is, most aren’t teachers. I can count on one hand those (in Detroit) who have their teaching certificate and coach.”

Jordan noted such successful PSL coaches like Derrick McDowell, Steve Hall and Robert Murphy who left high school to pursue a coaching career in college. Murphy guided Detroit Crockett to the Class B title in 2001 and is now the head coach at Eastern Michigan. McDowell has had two stints as a collegiate assistant coach, most recently at EMU. He’s since returned to coach at Detroit Western. Hall coached Detroit Rogers to three consecutive Class D titles (2003-05) before going to Duquesne University and Youngstown State as an assistant coach. Hall returned to Detroit last season and is in his second season as head coach at Detroit Cass Tech.

Jordan said they left high school to challenge themselves professionally, among other considerations. Voss said there are variables that influence how long a person lasts, in one school district or in coaching in general, that didn’t exist 20 years ago.

“Athletics have become pervasive in high school,” he said. “The whole booster situation you find in college is here. You can be winning but not winning enough. It’s a trickle down affect.

“Coaches complain about parents. Parents complain about playing time. High school sports is not as pure as it once was. Winning is way more important now. Now a coach comes in with a three-year window. You can have one or two down years, and the third you’d better win.

“Then there’s the pressure on your family. I’ve been lucky. My wife and I have had the players over for team dinners. We create a family atmosphere. It’s a change of society. I don’t envy the young coaches coming in.”

Community involvement has always been a priority for Voss. To keep a hand on the pulse, Voss heads the elementary basketball program within the Chippewa Valley school district. Games are held on Saturdays, and approximately 750 students take part.

“You have to have the right fit,” he said. “I’m in the right spot. You coach for different reasons when you get older. I’m enjoying the game. There’s a different level of satisfaction.”

Tom Markowski is a columnist and directs website coverage for the State Champs! Sports Network. He previously covered primarily high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

Tom Markowski is a columnist and directs website coverage for the State Champs! Sports Network. He previously covered primarily high school sports for the The Detroit News from 1984-2014, focusing on the Detroit area and contributing to statewide coverage of football and basketball. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for Oakland, Macomb and Wayne counties.

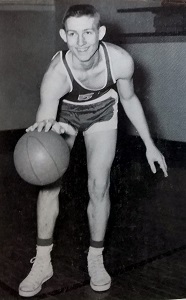

PHOTOS: (Top) Troy boys basketball coach Gary Fralick, left, is in his 32nd season coaching. (Middle) Detroit Renaissance boys coach Vito Jordan is following in the coaching footsteps of his father, Venias. (Below) Chippewa Valley boys coach Kevin Voss, left, is in his 35th season at his school. (Top and below photos courtesy of C&G Newspapers; middle photo courtesy of Detroit Public School League.)

63-Pointer Stirs Memories of UP Legends

February 29, 2020

By Ron Pesch

Special for Second Half

For the first time since 1970 – 50 years ago – and for only the 10th time in Upper Peninsula boys basketball history, a player has scored 60 or more points in a single game.

And that Houghton showing has stoked memories of legendary U.P. scoring showcases going back more than a century.

For the first time, the effort was for naught, at least from a win-loss standpoint, as Houghton dropped a nonconference road contest to Ishpeming 88-83 on Feb. 4. Brad Simonsen hit 23 of 45 field goal attempts, including 7 of 18 from beyond the 3-point arc, as Houghton pushed the play, hoping to narrow what had been a 10-point halftime margin. The 6-foot-6 senior, signed by Michigan Tech, was 10 of 13 from the free throw line and scored 24 points in the fourth quarter, ending the night with 63.

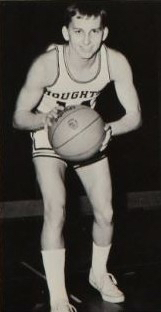

The performance topped Houghton’s school record of 60 points, set by Gary Lange in 1970. The total ranks 14th across the entire state for single game points in a contest, and tied Simonsen for sixth highest above the bridge. There, the mark equaled the top single-game output posted by Stephenson’s Mel Peterson, considered by many the greatest cager ever to come out of the Upper Peninsula.

“Marvelous Mel”

Peterson was the son of a minister and one of 10 children (and eight boys). His older brother, George, broke the U.P. scoring record in 1949 with 44 points in a game for Stephenson High School. The family moved away from the Upper Peninsula following George’s graduation, ultimately landing in southeastern Idaho.

There, Mel emerged as an outstanding athlete for Idaho Falls High School. Standing 6-foot-4½, Peterson’s growth occurred mostly during his freshman year.

There, Mel emerged as an outstanding athlete for Idaho Falls High School. Standing 6-foot-4½, Peterson’s growth occurred mostly during his freshman year.

“I played quite a bit on the varsity my sophomore year,” recalled Peterson recently. “My junior year I started out very, very slow but ended up very good. (However,) I fractured my ankle with about a minute to go in the semifinals of the (1955) state tournament, which we won.”

Peterson led all scorers with 25 points and dominated the boards that night, but had to be helped from the floor, then didn’t play in the title contest. “We lost the state tournament by three points, (43-40 to Kellogg). I was a cheerleader. … It would have been fun to play in the final game.”

When his father received a call to serve the Mission Covenant Church in Wallace, Michigan, about seven miles south of Stephenson, the family returned to the Upper Peninsula for Peterson’s senior year.

“At that time, it was nothing like it is now, where you can find anything about anybody. Then, that wasn’t the case at all,” Peterson said. “So, when we came back, no one had any idea of where I lived before, if I played or not.”

Indeed, prior to football season, one newspaper report indicated Peterson had transferred in from North Dakota, while another listed him as coming from Illinois. Regardless, Peterson emerged as a solid football player at Stephenson High in the fall of 1955. But it was on the basketball court where his scoring and rebounding prowess quickly loomed. He opened the season with 33 points in a win over Gladstone, despite fouling out early in the fourth quarter.

By January, the media had taken to calling him “Marvelous Mel” as Peterson averaged 32.3 points in his first half-dozen games for the Eagles. He drove Stephenson to a 15-1 regular-season record, posting 11 games over 30 points and scoring more than 40 in six.

On Jan. 21, 1956, he poured in 63 points in an 89-44 win over Manistique, shattering his brother’s school record. Mel nailed 25 of 38 shots from the field and 13 of 16 from the free-throw line. At the time, the scoring total exceeded the previous known best in the U.P. of 60 points, scored by Norbert Purol in February 1952. (Purol, from Ironwood St. Ambrose, would later play two seasons of AAU ball in Chicago before matriculating at Kentucky Wesleyan, earning four letters between 1956 and 1959. Wesleyan ended the 1957 season as runner-up to Wheaton College in the inaugural NCAA Small College Tournament – now known as Division II.)

“I don’t remember a great deal about a lot of it. That was so long ago,” said Peterson, laughing. “I guess the thing I appreciate most about the game was that my coach (Duane “Gus” Lord), let me play the whole game, which didn’t happen real often. Probably the thing I remember most about the whole year is that we played a Catholic school, Lourdes, from Marinette, Wisconsin. The first game we played them we beat them 110 to 44. The second game we lost 68-66.”

Peterson’s regular-season total of 570 points also exceeded Purol’s U.P. record of 556 posted over 19 games in 1952. His regular-season average, which had climbed to 35.6, topped the previous best of 29.6, posted by Pete Kutches in 1952 for Escanaba St. Joseph. Then Peterson pushed the per-game-average even higher in the postseason.

Seeing more playing time in the playoffs, “Marvelous Mel,” notched more than 30 points in all seven postseason games (exceeding 40 in three of the contests and 50 once), leading Stephenson to the MHSAA Class B championship win against Detroit St. Andrews in sudden-death overtime, 73-71. There he scored the game-tying bucket with 17 seconds remaining in the three-minute extra frame, and then sunk the game winner 26 seconds into sudden death, where the first team to gain a two-point advantage was proclaimed the victor. That 1956 season saw three of the four basketball championships awarded to U.P. teams.

Peterson finished with 849 points on the year – at the time the best single-season performance in MHSAA history. He averaged 36.9 points across 23 contests – currently eighth in the MHSAA record book.

Following graduation, Peterson nearly signed to play at the University of Minnesota, but felt a better fit at Wheaton College, outside Chicago. There, he earned three All-American honors. As a freshman in 1957, he led Wheaton to victory in that first NCAA Small College Tournament championship game against Wesleyan, earning Most Outstanding Player honors along the way. Today, he remains Wheaton’s all-time leader in career points, points per game, field goals made and career rebounds, all accomplished “without the benefit of a 3-point line, which had yet to be implemented.”

Peterson, who helped the USA team win gold at the 1963 Pan American Games in Sao Paulo, Brazil, played two games for Baltimore in the National Basketball Association (NBA) before a heart condition sidetracked his career. Once the issue was repaired, he returned to play 134 games over three seasons in the American Basketball Association, earning an ABA league championship with the Oakland Oaks in 1969. In 2019, he was inducted into the Small College Basketball National Hall of Fame.

The High-Scoring Sixties

Roger Roell, a senior at Channing, topped Peterson’s U.P. single game record with a 67-point performance in early January 1960 by dropping 31 field goals and five free throws in a 105-55 win over Michigamme.

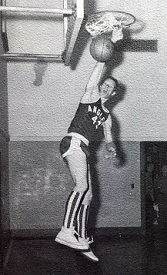

Just over seven weeks later, Jim Manning scored 69 for Trout Creek against Amasa in another lopsided affair, 140-47 (then, a U.P. record for highest team score. The team’s 44 points in the fourth quarter was also a U.P. mark at the time. Trout Creek’s coach, Bruce Warren began substituting in the second quarter).

Just over seven weeks later, Jim Manning scored 69 for Trout Creek against Amasa in another lopsided affair, 140-47 (then, a U.P. record for highest team score. The team’s 44 points in the fourth quarter was also a U.P. mark at the time. Trout Creek’s coach, Bruce Warren began substituting in the second quarter).

Manning, a junior, finished the 1959-60 season as the first player in U.P. history to exceed 600 points in one regular season, totaling 608 over 18 games. He would later pitch in the Major Leagues.

Roell finished second with 569 points in 18 regular-season contests. Third on the regular-season scoring list was another junior, Erwin Scholtz of Hermansville, who tallied 505 across 18 games.

As a senior, the 6-foot-5 Scholtz would post 71 points against Channing, a new benchmark for points in a game in the Upper Peninsula.

Or was it?

The Master’s Thesis

Perhaps because of the media coverage of Scholtz’s accomplishment, in 1962 the Crystal Falls Diamond Drill ran an article detailing the recently unearthed exploits of Ed Burling some 50 years prior. Richard Mettlach, football and baseball coach at Crystal Falls, had uncovered the Burling story.

Mettlach, “in the process of preparing a history of local high school sports which he submitted as a part of the preparation for his master’s degree … discovered that the newspaper records of the early years of high school basketball tell of a match between Iron River and Crystal Falls (played during the 1910-11 season).”

Crystal Falls had downed Iron River, 107-27, according to Mettlach’s research, and Burling had scored all but 10 of Crystal Falls’ points.

“Basketball was different in those days,” said Burling when interviewed by the Diamond Drill in January 1962. Then 68 years old and working as the postmaster in Crystal Falls, he recalled, “when one man was hitting the basket well, the rest of the team fed him the ball and let him shoot. I couldn’t miss that night.”

According to the article, “Burling said as he recalled the game, he made 98 points that night. It appears that 97, however, reportedly verified in two newspaper accounts of the game, will have to be the figure used in the record book.”

Burling recalled that the majority of his shots were from in front of the basket and that rules of the day allowed the top shooter on the team to attempt the free throws.

“The 97 point scoring record would probably have never been uncovered if it had not been for Mettlach’s research,” added the Diamond Drill.

Three more U.P. additions

In 1966, Bob Gale of Trout Creek scored 60 against Mercer, Wisconsin. Gale would later play at Michigan State.

Houghton’s Lange scored his 60 as the Gremlins walloped Painsedale Jeffers, 134-62, on January 23, 1970. One week later, Larry Laitala dropped 65 as Champion crushed Felch, 114-71.

Houghton’s Lange scored his 60 as the Gremlins walloped Painsedale Jeffers, 134-62, on January 23, 1970. One week later, Larry Laitala dropped 65 as Champion crushed Felch, 114-71.

“We had a very good team that year. We had a lot of wings and normally, I wouldn’t play the whole game. My coach was Dominic Jacobetti (who played at Negaunee St. Paul, then Northern Michigan University) and he was a pretty prolific scorer in the U.P. It was one of those nights where the rim was real big,” recalled Laitala, chuckling.

Laitala finished second to Lange in regular-season scoring, 557 to 523, with each athlete playing 17 games.

“Houghton is possibly the best team in any class in the Upper Peninsula,” wrote Hal Schram in the Detroit Free Press, who predicted an MHSAA state title for the team noting that many felt Lange was the top player north of the bridge. The Gremlins, at 17-0, finished as the top-ranked team in Class C in the weekly press polls assembled by the Free Press, The Associated Press and United Press International.

But the season ended earlier than expected for both teams. Houghton fell to St. Ignace in a Regional Semifinal.

“We were beat by our archrival, Republic (61-55) in the first game of the (Class D) Districts, which was kind of an upset,” added Laitala.

Prior to Simonsen’s accomplishment, Lange and Laitala were the most recent players above the Straits of Mackinac to equal or exceed the 60-point minimum established in the MHSAA record book.

The Challenge of Traceability

With modern-day electronic archiving of a number of the state’s newspapers and the accessibility of newspapers on microfilm, an effort has been made to add dates to single-game records, where once only the season of accomplishment was listed. The work continues.

Today, more than 100 years later, the “two newspaper accounts” used back in the 1960s for verification of Burling’s scoring accomplishment have not resurfaced. Hence, neither the date of the game, nor details from period accounts are available for study. That, combined with knowledge that basketball games from the time were usually low-scoring affairs, means doubt is still cast on the mark.

After investigation, the record was accepted by Crystal Falls historian Malcolm McNeil and U.P. sports archivist, Jim Trethewey, a former sports editor of the Marquette Mining Journal who travelled to Crystal Falls to interview Burling. MHSAA historian Dick Kishpaugh ultimately added the performance to the state record book. Questions about the legitimacy of Burling’s total began almost immediately and have resurfaced every 10 years or so. Todd Schulz, a former sports columnist at the Lansing State Journal, wrote extensively on the chase in 2012.

After investigation, the record was accepted by Crystal Falls historian Malcolm McNeil and U.P. sports archivist, Jim Trethewey, a former sports editor of the Marquette Mining Journal who travelled to Crystal Falls to interview Burling. MHSAA historian Dick Kishpaugh ultimately added the performance to the state record book. Questions about the legitimacy of Burling’s total began almost immediately and have resurfaced every 10 years or so. Todd Schulz, a former sports columnist at the Lansing State Journal, wrote extensively on the chase in 2012.

One of the individuals still working to help solve the mystery is Al Anderson of Crystal Falls.

The Diamond Drill was a weekly paper during Burling’s high school days, and newspapers of the time generally didn’t separate prep sporting news into sections. When reported upon, accounts of high school games were usually included in a ‘School Notes’ column.

The season was, without question, a success. “Winning eight out of ten games played, and having three challenges refused, the local basket ball team lay claim to the U.P. championship for the season of 1910-11,” stated the Diamond Drill in the March 25, 1911 edition.

Still, reports uncovered from the period publication continue to cast doubt on the plausibility of the feat occurring in a high school game. “… More basket ball and less indoor foot ball next time will look better to the audience,” noted the newspaper about a 17-10 victory over Niagara, Wis., in mid-December 1910.

“The basket ball game last night resulted in a dispute near the end of the last half with the score 13 to 12 in favor of Crystal Falls. Iron Mountain disputed a decision by the referee and withdrew from the floor,” was the account in the Feb. 18, 1911 edition of the paper.

“There’s an article that was cut out of the physical copy of the December 10, 1910 Diamond Drill,” reports Anderson, who’s been seeking confirmation in fits and starts for nearly a decade. “It looks like it could be the ‘School Notes.’ portion. It’s missing on microfiche copies as well. Perhaps that’s it.”

So the chase to verify continues.

2019-20 season brings sudden burst

Sophomore phenom Emoni Bates of Ypsilanti Lincoln is the latest prep player to etch his name in the MHSAA record book for scoring 63 points. He accomplished the feat in a 108-102 double-overtime win against Chelsea two weeks after Simonsen’s accomplishment. Statewide, that means 34 players have now scored 60 or more points in a game – 30 boys (10 in the U.P. and 20 in Lower Michigan) and four girls (one in the U.P and three in the Lower Peninsula).

Will the list be reduced by one? Time and additional research will tell.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS: (Top) Brad Simonsen celebrates becoming Houghton's all-time leading scorer Wednesday. (2) Stephenson's Mel Peterson. (3) Trout Creek's Jim Manning. (4) Houghton's Gary Lange. (5) Trout Creek's Bob Gale. (Top photo courtesy of Houghton Daily Mining Gazette. Peterson photo courtesy of Upper Peninsula Sports Hall of Fame. Houghton and Trout Creek photos courtesy of those schools' yearbook departments.)