1970-1995: Detroit, Flint Ruled Class A Boys Basketball

By

Ron Pesch

MHSAA historian

March 7, 2022

Geographic domination.

It really hasn’t happened on the basketball court in the MHSAA’s top classification since the mid-1990s.

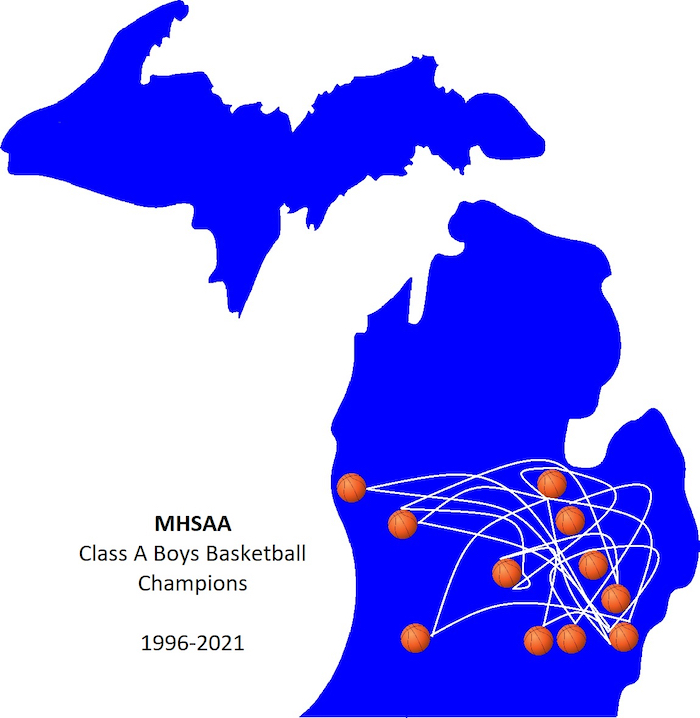

Class A state titles – designated Division 1 in basketball since 2019 – have bounced around Michigan over the last 25-plus years like, well, an over-inflated wayward basketball. Kalamazoo Central, Pontiac Northern, and Clarkston grabbed back-to-back titles between 1996 and 2021. The Saginaw area locked down five Class A crowns within that stretch; Arthur Hill snagged one in 2006, while Saginaw High immediately followed with two in a row in 2007 and 2008. The Trojans also won in 1996 and 2012. Greater Lansing has three titles – one by Lansing Everett, another by Lansing Waverly, then one by Holt High School – about eight miles outside the city limits.

Then it’s single titles to Grand Rapids Ottawa Hills, Rockford, Muskegon, Ann Arbor Pioneer, and Ypsilanti Lincoln. Metro Detroit schools Romulus, Pershing, Central, Western, and U-D Jesuit also have single championships during that span.

Then it’s single titles to Grand Rapids Ottawa Hills, Rockford, Muskegon, Ann Arbor Pioneer, and Ypsilanti Lincoln. Metro Detroit schools Romulus, Pershing, Central, Western, and U-D Jesuit also have single championships during that span.

But from 1970 to 1995, a trip to the Finals to watch the ‘A’ title game meant – with rare exception – you were watching a team from Flint or Greater Detroit. Or both.

Flint: Home of the Vikings

Opened in the fall of 1928, Flint Northern had been the Vehicle City’s top basketball school, winning Class A titles in 1933, 1936, 1939, and 1940 under coach Jim Barclay, then another in 1947 under Les Ehrbright. The Vikings also advanced to the state championship game in 1954 under Carl Stelter, losing to Muskegon Heights in overtime, 43-41.

Then, things went mostly quiet for the next decade and a half.

Jack Marlette was only the fourth varsity basketball coach in school history. Since arriving at Northern in 1949, he had served as head coach in tennis and golf, sophomore coach in basketball and football, junior varsity coach in basketball and football, equipment manager, and head trainer.

Midseason 1955, he replaced Stelter as the varsity basketball coach, when Stelter was named a principal within the Flint school district.

“Marlette coached teams posted a record of 112 victories and 99 defeats,” stated Len Hoyes in the Flint Journal when the coach stepped down in March 1967. “Included are six city championships, two districts, and a Saginaw Valley Conference crown in 1956.” His 1957 team reached the MHSAA Quarterfinals, losing to East Detroit.

With the announcement, Northern wooed 36-year-old Dick Dennis to take his spot come the 1967-68 season. Dennis’ teams had posted an impressive 105-21 varsity record at Alpena High School over seven seasons. Perhaps more impressively, his teams had beaten two of the Flint area’s finest in the MHSAA Regional round in 1966.

Dennis agreed to the move to Northern, “but had one important request,” stated reporter Bruce Johns in the Journal. “He wanted Bill Frieder as the junior varsity coach.”

Frieder, who would ultimately become a legendary basketball figure in Michigan, had landed his first basketball job as JV coach under Dennis at Alpena during the 1965-66 school year.

“… (A) son-in-law of Larry Laeding, former Saginaw High coach and a former player for the Trojans, Freiders (sic) had a 20-11 JV record for two years,” noted the Journal at the time of the hiring. (Laeding’s Saginaw team had won the Class A basketball championship in 1962.)

Dennis’ varsity squad posted an 11-6 record that first year, followed by a 13-6 mark in 1968-69, the program’s best season in 10 years. Frieder’s 1967-68 JV Vikings finished with a 13-3 mark, earning a share of the Saginaw Valley Conference’s title. In his second year, Frieder’s squad went a flawless 16-0.

But a teacher’s strike in Flint the following school year caused Frieder to resign from his position.

“At this point, I want to emphasize that I am highly opposed to teachers’ striking as I feel it sets a poor example for children and such an act reflects upon me personally,” stated Frieder in a letter of resignation to the Flint Board of Education.

Unable to work around it, he stepped aside.

Another shake-up

After three seasons at the helm, in May 1970, Dennis accepted an assistant principal position within the district. Northern administration interviewed nine “capable” candidates for the opening, including the former JV coach.

“Out of the candidates, we felt that Bill was the best qualified,” Northern athletic director Jim Fowler told the Journal’s Dean Howe 22 days later. “Bill is familiar with our situation at Northern, he’s familiar with the kids and unquestionably a fine coach.

“… it was Dennis’s strong recommendation that finally swung the gavel Frieder’s way,” stated Howe.

“Bill has a tremendous ability to get along with the kids,” Dennis had told the Journal in 1969. “… there are some coaches who never accomplish this. Bill’s two outstanding characteristics are his loyalty to the job and kids and his tremendous amount of pride.

“He just loves the game. Bill works just as hard at developing good citizens as he does to winning.”

Under Frieder, the Vikings quickly returned to the state spotlight, winning two straight MHSAA Class A championships in 1971 and 1972.

For the first time since 1954, Northern enjoyed final round success. Frieder’s 1971 Vikings, powered by senior Tom McGill and the Britt brothers, Wayman and James, clipped the taller – and favored – crew from Detroit Kettering, led by Lindsay Hairston, 79-78.

For the first time since 1954, Northern enjoyed final round success. Frieder’s 1971 Vikings, powered by senior Tom McGill and the Britt brothers, Wayman and James, clipped the taller – and favored – crew from Detroit Kettering, led by Lindsay Hairston, 79-78.

A year later, Frieder’s team beat Pontiac Central, a squad it had defeated twice during the regular season, 74-71. It was the Vikings’ 33rd-straight victory.

Frieder returned for the 1972-73 season. The Vikings posted an 18-7 record and won a District title. In July, his JV coach from the past two seasons, Grover Kirkland, was named head basketball coach at Flint Northwestern. In August, Frieder resigned. Rumors had been flying that he might go to the University of Michigan as an assistant. A Saginaw native, Frieder stated his “retiring is a result of many things.” Primarily, he planned to return to Saginaw to go into the produce business with his father.

The rumors, it turned out, were true. A little over a month later, the University of Michigan appointed Frieder as assistant basketball coach.

“We think it’s very fine to have a man of Bill’s caliber on our staff,” said Johnny Orr, Michigan’s head men’s basketball coach.

“If at this point in my life, I could describe the job I wanted most, the thing I wanted most to do in my life, this would fit it to a tee,” said Frieder at the time of the announcement.

Bill Troesken, 29, who had stepped down in June of 1973 after three years as varsity coach at Flint Powers Catholic, was hired by Northern to replace Frieder. His team would grab another Class A championship in March 1978.

A Long Drought

Flint’s oldest high school, Flint Central, was opened in 1875. Incredibly, the boys basketball team never won a state title – or even appeared in a championship game – until coach Stan Gooch arrived on the scene.

“Gooch, who starred in basketball at Flint Tech High, Flint Junior College, and Central Michigan (University), began his coaching career as bench boss of the sophomore team at Central High in 1959,” recalled Brendan Savage for MLive in 2008 at the time of his induction into the National High School Athletic Coaches Association Hall of Fame. “He took over the reins of the junior varsity the following year and was promoted to varsity coach in 1966.” Gooch guided Flint Central to its first state championship game in 1967, but Central was trounced by Detroit Pershing, a PSL squad considered by many to be the greatest basketball team in Michigan prep history. Guided by coach Will Robinson, the Doughboys were led on the court by future NBA players Spencer Haywood and Ralph Simpson.

Gooch resigned following the 1967-68 season to become head coach at Flint Junior College (which was converted into a countywide college, and rebranded as Genesee Community College in 1969, then renamed Mott Community College in 1973). After 10 seasons, Gooch stepped down, and within months, he replaced his replacement at Flint Central, Clif Turner, who had guided the program through the 1977-78 season.

Central then won three straight Class A titles from 1981-83, helping to build the legend of Flint basketball.

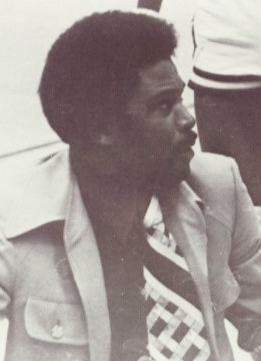

Then it was Northwestern’s turn. In both 1984 and 1985, Coach Kirkland’s Wildcats beat Detroit Southwestern. With those wins, the Flint city schools had now won six of the last eight titles.

“City of Champions defies explanation” trumpeted the Journal at the end of March 1985, after Northwestern had won Class A and Flint Beecher had won the boys title in Class B.

“No single factor can be pinpointed as the reason Flint has dominated,” wrote Phil Pierson under the headline, “while metropolitan Detroit, an area approximately 10 times larger, has failed to win a Class A Championship since 1979.”

Northwestern’s Glen Rice “became the area’s first recipient of the Mr. Basketball award presented by the Michigan High School Basketball Coaches Association and has been named to the Parade and Basketball Weekly All-American teams. (Beecher’s Roy Marble finished second, while Central’s Terence Greene finished fourth in Mr. Basketball balloting).

Was this success the opportunity to play year-round, asked Pierson. Coaching? The talent on the court?

Other areas across the state featured these same strengths, concluded the writer. “It may just be that the reason for Flint’s success is too obvious to be considered by the philosophers: the cyclical nature of high school sports.

“There was nothing wrong with Flint basketball from 1948-70 when there were no state Class A or B championships. Other teams and programs were just better.”

The Return of the PSL

It took five years after the return to the MHSAA Tournament before the PSL earned a Class A title with that ’67 Pershing squad. The next arrived in 1970, again by Pershing, then in 1973 by Southwestern, and again in 1979 by Mackenzie. Class A was won by Metro Detroit in 1974, by Birmingham Brother Rice, in 1975 by Highland Park, and in 1976 by Detroit Catholic Central.

From 1971 to 1985, Flint’s public school champions had defeated Pontiac Central twice, and PSL teams from Kettering, Murray-Wright, and, famously, Southwestern, on four straight occasions between 1982 and 1985.

On only two occasions between 1975 and 1995 did the Class A crown leave the city of Flint or Metro Detroit. In both instances, it landed in Lansing. In 1977, the Lansing Everett Vikings, led by Earvin Johnson – nicknamed “Magic” by the press – wrestled it away by downing Brother Rice in a 60-56 overtime thriller. In 1980, Lansing Eastern, powered by the state’s first Mr. Basketball winner, Sam Vincent, did the same, with a 64-53 victory over Highland Park.

The Cycle of Basketball

As soon as the ink dried on Pierson’s words, it seems, the cycle rotated.

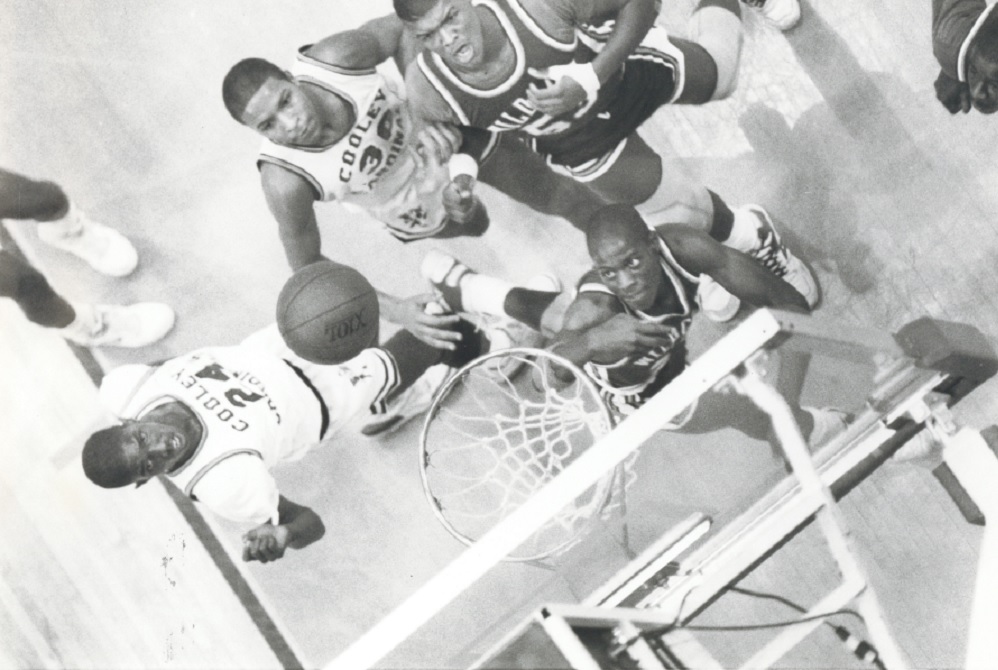

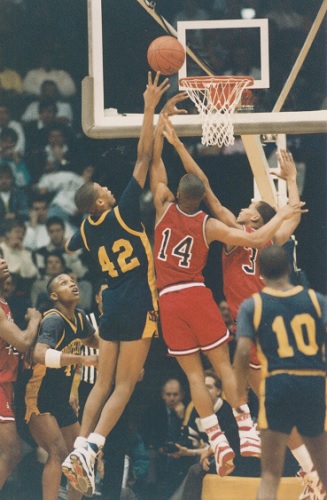

Romulus took down Southwestern in ’86 before the PSL took control of Class A beginning with the 1987 season. Cooley, coached by Ben Kelso, snagged the first of three straight that year. After finishing as runner-up in seven of the previous eight title games, Southwestern, coached by Perry Watson, grabbed back-to-back victories in ’90 and ’91. Coach Johnny Goston’s Pershing teams beat Benton Harbor for consecutive titles in 1992 and 1993. Then Murray -Wright, coached by Robert Smith, captured its first crown in 1994.

On four of the eight occasions between 1987 and 1994, the Class A game featured an all-PSL card.

The 1995 Class A final wrapped the amazing run as No. 1-ranked Flint Northern, powered by Mateen Cleaves’ game-leading 28 points and Antonio Smith’s 24 points and 15 rebounds, decimated No. 2 Pershing, 86-64 before a crowd of 11,179 at the Breslin Center. Northern had trailed 44-37 at the half.

The 1995 Class A final wrapped the amazing run as No. 1-ranked Flint Northern, powered by Mateen Cleaves’ game-leading 28 points and Antonio Smith’s 24 points and 15 rebounds, decimated No. 2 Pershing, 86-64 before a crowd of 11,179 at the Breslin Center. Northern had trailed 44-37 at the half.

It was Northern’s first title since 1978. It would also be the program’s last. The introduction of “school of choice” in Michigan in 1996, combined with plunging birth rates in the U.S. that peaked in 1978, meant upheaval in enrollment across the state’s public schools. In Flint, declining enrollment – also impacted by the pending closure of a massive automotive manufacturing complex operated by General Motors known as “Buick City” – forced the closure of Central following the 2008-09 school year. Northern closed in 2013. Following the 2017-18 school year, Northwestern and Flint Southwestern merged, leaving Southwestern as the city’s lone high school.

In Detroit, Northern, Mackenzie, and Murray-Wright were among four high schools closed by the Detroit Public Schools in 2007 due to cost constraints and declining enrollments. Cooley was shuttered in 2010. Southwestern, dedicated in 1922, and Kettering, opened in 1965, both closed in 2012.

Of the 26 Class A title games waged between 1970 and 1995, Flint City Schools and the PSL teams each won nine of those contests. On 15 occasions, the championship game featured a match-up of Flint and Detroit PSL teams. On only seven occasions did schools from outside Wayne, Oakland, or Genesee counties ever crash the championship party. Saginaw High School ended with runner-up honors in 1973, 1976, and 1990, with Lansing and Benton Harbor High Schools being the only others.

Parade of Talent

Basketball junkies attending title games during those years watched an incredible collection of talent come out of those teams from Flint, the PSL and metropolitan Detroit during the span.

On the coaching side:

► Frieder ended up as head coach at Michigan with the 1980-81 season, then Arizona State in 1989.

► Gooch compiled over 400 varsity wins and 86 JV victories during his time at Flint Central.

► Kirkland ended his basketball coaching career in 2000 as Flint’s all-time winningest varsity coach, compiling a 518-148 mark. His Wildcats compiled 60-straight wins between January 1984 and February 1986 and presently rank No. 3 in consecutive wins in state history. In 2020, Detroit Free Press writer Mick McCabe named Northwestern’s 28-0 team from 1985 as the greatest boys basketball team he covered in his 50 years of reporting.

► Southwestern’s Watson served as an assistant at Michigan for two seasons, then guided the men’s basketball team at the University of Detroit Mercy from 1993 to 2008, compiling a 258-185 record over 15 seasons.

► Kelso, a Flint Southwestern graduate who did not play high school basketball but ended up as the all-time scorer at Central Michigan when he graduated in 1973, would be a finalist for the head coaching spot at CMU in 1997. At Cooley from 1984 through 1998, he later served as an assistant basketball coach at Kansas State in 2005-06.

► Kettering’s Charles Nichols, on hand since the school opened, coached tennis, football, and track during his first years at the school. With the 1970-71 season, he took over basketball coaching duties from Walt Jenkins, guiding the team for four campaigns. In December 1974, he joined Dick Vitale’s coaching staff at the University of Detroit for parts of two seasons. He returned to Kettering in 1978 as athletic director, then later served as assistant director of the PSL until his retirement in 2002.

The players included:

Flint

► Central’s Eric Turner, Marty Emery, Mark Harris, Keith Gray, Terence Green, and Darryl Johnson.

► Northern’s Terry Furlow, Dennis Johnson, Gary Pool, Antonio Smith, and Mateen Cleaves.

► Northwestern’s James Person, Jeff Grayer, Glen Rice, Andre Rison, Anthony Pendleton, and Daryl Miller.

Detroit PSL

► Cass Tech’s Tony Jamison and William Mayfield.

► Cooley’s Yamen Sanders, Earl Stark, Rafael Peterson, Michael Talley, and Daniel Lyton.

► Kettering’s Lindsay Hairston, Joe Johnson, Eric Money, and Coniel ‘Connie’ Norman.

► Mackenzie’s Steve Caldwell and Dave Traylor.

► Murray-Wright’s Willis Carter and Robert Traylor.

► Northern’s Katu Davis and Leonard Bush.

► Pershing’s Phil Paige, Robert Hawkins, Calvin Harper, Willie Mitchell, Carlos Williams, Todd Burgan, and Winfred Walton.

► Southwestern’s Darryl Robertson, Antoine Joubert, Clarence Jones, Sam Sillmon, Tarence Wheeler, Anderson Hunt, Loren Clyburn, James Hunter, Jalen Rose, Voshon Lenard, and Howard Eisley.

Metro Detroit

► Birmingham Brother Rice’s Will Franklin, Kevin Smith, and Tim Andree.

► Detroit Catholic Central’s Mike Prince and David Abel.

► Highland Park’s Terry Duerod, Percy Cooper, and Renardo Brown.

► Pontiac Central’s brothers Campy, Larry and Walker D. Russell; Larry Cole, Tim Marshall, and Clyde Corley.

► Romulus’s Terry Mills, and Stevie Glenn.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

Ron Pesch has taken an active role in researching the history of MHSAA events since 1985 and began writing for MHSAA Finals programs in 1986, adding additional features and "flashbacks" in 1992. He inherited the title of MHSAA historian from the late Dick Kishpaugh following the 1993-94 school year, and resides in Muskegon. Contact him at [email protected] with ideas for historical articles.

PHOTOS (1) Detroit Cooley's Rafael Peterson (24) and Benson Maurice match up with Flint Northwestern's Archie Munerlyn (53) and Reggie Richardson during the 1988 Class A Final. (2) The Class A/Division 1 championship has been won by teams across the southern half of the Lower Peninsula over the last 25 years. (3) Grover Kirkland, here in 1975, built Flint Northwestern into a power. (4) Detroit Southwestern's Jalen Rose (42) and Cooley's Michael Talley (14) work to grab a loose ball during the 1989 Class A Final. (Photos courtesy of the Detroit News [1] and Gary Shook [4], or collected by Ron Pesch.)

Lessons From Banner Run Still Ring True

February 20, 2019

By Tim Miller

Mio teacher, former coach and graduate

If you were to travel to northern Michigan to canoe or fish the famous AuSable River, you might find yourself in a small town named Mio.

With one stoplight and a host of small businesses that line Main Street, Mio is well known for its access to the AuSable River and its high school sports team. And like so many small towns across America, the school is the main focal point of the community. Mio is the home of the Mio Thunderbolts, which is the mascot of the only school in town.

On Saturday, December 29, head boys basketball coach Ty McGregor and fans from around the state gathered in the Mio gymnasium to welcome back two former boys basketball teams. The two teams being honored that night were the 1989 state championship team who went undefeated and the 1978 boys basketball team who made it to the Semifinals.

As we stood there watching the former players of those teams, and coach of the 1978 team Paul Fox, make their way across the gym floor, we were reminded of the deceased players Cliff Frazho, Rob Gusler, Dave Narloch and John Byelich – the coach of the 1989 state championship team – that were no longer with us. All of them leaving us way too soon and a reminder of how fragile life can be.

The ’89 team would be a story in itself. That team was the most dominating team in Mio’s history.

After recognizing these two teams and visiting with many of them in the hallway, I stepped into the gym and began looking at the banners hanging from our walls. I found the state championship banner that the ’89 team won and the ’78 banner, and I began remembering those teams and how they brought so much excitement, happiness and pride to our small community.

Like so many schools throughout the state, the banners are a reminder of a team’s success and the year that it was accomplished. It’s a topic of conversation as former players share their memories with others about the year they earned their spot in history.

However, hanging on the south wall of the gym, all by itself, is a banner that only hangs from the walls of the Mio AuSable gym. No other school in Michigan has one like it. It has a weathered look, and the color has slightly faded over time. It’s been the conversation piece at deer camp, restaurants, and any other social gathering concerning Mio sports history. Basketball players throughout the state have dreamed of taking it away, but none have succeeded. It’s been hanging there for close to 40 years.

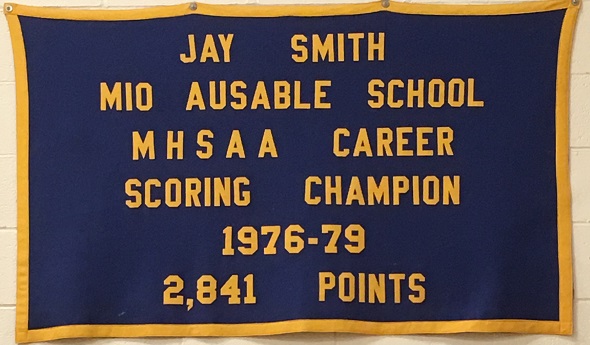

It reads:

Jay Smith

Mio AuSable School

MHSAA Career Scoring Champion

1976 – 1979

2,841 points

That banner represents something far greater than one person’s accomplishments. The story of how it got there and why it hasn’t left is a lesson that every sports team should learn – such a rare story in teamwork, coaching, parental support, the will to win, and the coach who masterfully engineered the plan.

The night Jay Smith broke the state scoring record, the Mio gym was packed with spectators from all parts of Michigan. The game was stopped and people rose to their feet to acknowledge the birthplace of the new record holder. After clapping and cheering for what seemed like an eternity, the ceremony was over and the game went on.

Although I wasn’t on the team, like so many people from Mio, I followed that group of basketball players from gym to gym throughout northern Michigan.

I had a front row seat in the student section where every kid who wasn’t on the team spent their time cheering for the Thunderbolts.

We were led by our conductor, “Wild Bill,” who had a knack for writing the lyrics to many of the cheers the student body used to disrupt our opponents or protest a referee’s call.

The student section was also home to the best pep band around. During home games they played a variety of tunes that kept the gym rocking. They were an integral part of the excitement that took place in that gym, game after game.

I also ate lunch and hung out at school with some of those guys. I got to hear the details of the game, the strategy, the battles between players, and the game plan for the next rival’s team.

I also ate lunch and hung out at school with some of those guys. I got to hear the details of the game, the strategy, the battles between players, and the game plan for the next rival’s team.

I remember the school spirit, the pep assemblies, and the countless hours our faithful cheerleaders put into making and decorating our halls and gym with posters.

It was like a fourth of July parade that happened every Tuesday and Friday night. The bleachers were filled with people anxiously awaiting tip off.

Showing up late meant you were stuck trying to get a glimpse of the game from the hallway.

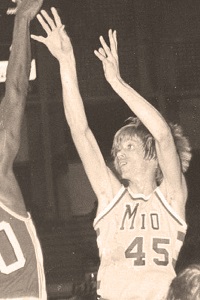

So here’s what I saw. Jay Smith was a tall, skinny kid who could shoot the ball with such accuracy that it must have been miserable for opposing coaches and players. Once it was in his hands, they had two options: watch him score or foul him and hope that he missed the free throws.

If you fouled him, you gambled wrong. He stood there and calmly shot the ball through the hoop with the sound of the net swishing as opposing players and coaches watched helplessly.

If you chose to let him shoot, you lost that bet too.

He shot often and rarely did he miss. It was no secret to our opponents or Jay’s teammates who would be doing the bulk of the shooting in Mio.

The game plan was simple: get the ball to Jay and watch him score. The Thunderbolts were coached by Paul Fox, a teacher at the school. He was demanding and intense as a coach, and his players played hard and respected him both in school and on the court. It wasn’t until I had the opportunity to coach a couple of high school teams that I realized and recognized what an incredible job he did.

I also realized what an outstanding group of players he was blessed to coach.

He was a step ahead of everybody.

Like Bill Belichick the famous coach of the New England Patriots, Paul Fox understood how to build a team around one person. He convinced everyone on the team that the way to the promised land was through the scoring of Jay. However, the type of players who buy into such a plan have to be special. And they were. Jay was blessed his first two years on varsity. He was surrounded by a very talented group of ball players who allowed him to be successful.

His last two teams weren’t as talented, but just as special.

Most of those guys were classmates of mine, so here’s what I can tell you.

Not one time during that stretch did I ever hear one of them complain about playing time. There was no pouting on the bench or kicking it because you were taken out.

No one complained the next day about their stats. They were happy to win, and if that meant Jay shooting most of the time, that was okay with them. After the game, no one ran to the scorer’s table to check their stats. Or went off in the corner of the locker room to act like a preschooler in timeout. Their parents didn’t march over to the coach and demand answers on why their son wasn’t playing or shooting more. Players didn’t quit the team because their individual needs weren’t being met. There were expectations from the coach, the parents, and everyone else involved. After each home game, the whole community gathered at the local bar/ bowling alley. Players, parents, and fans were happy their team had won and celebrated together in the victory. It was a simple blueprint that every sports team should follow.

Forget about your own personal gratification and do what’s best for the team.

It’s a lost concept these days. And the question many of us in Mio talk about from time to time is will the record ever be broken?

There’s more than one factor to consider when discussing the topic.

Jay set that record long before the 3-point shot was implemented.

Can a coach like Paul Fox assemble a group of players who would put their ego aside and desire winning more than their own personal satisfaction?

Can you find a humble kid like Jay who would crush the dreams of opposing teams with his shooting ability?

Can you find a group of parents out there willing to watch a kid like him put on a show, game after game, and not be offended?

Can you find a student body like the one we had to fill the student section with loud, rowdy fans?

Can you find a student body like the one we had to fill the student section with loud, rowdy fans?

The scoring banner represents the scoring accomplishments of Jay. And to his credit, I never once heard him brag about his success on the court.

He simply said, “We won.”

But that banner represents more than points. It’s an amazing story of what happens when a group of people come together with a common cause – the will to win.

What we saw during that time was special!

The state scoring record was set by Jay and a large list of supporting teammates who helped him.

He was fortunate to have a coach who understood how to manage and convince a group of players to buy into his system.

A group of parents who understood what was going on and supported it.

A student body section that rattled the best players from the other teams game after game.

A dedicated group of cheerleaders who spent countless hours making posters to decorate our school with pride.

A pep band that brought their best sound, game after game.

A teaching staff who understood how a bunch of kids wanted to get ready for the next big game, and gave us their blessing.

It was the culture of our school and community. Get ready for the game.

The anticipation, those long lines waiting outside in the cold, those packed gyms, that noise.

It was all part of it.

Perhaps somewhere in Michigan a group of coaches, players, parents, teachers, and fans could copy the formula from the ’70s that brought our team, school, and town so much success.

If a coach can find a group of players that only care about one thing, and that’s winning, it can be done. Doing that will require a group of people who think they understand the concept to execute it. As a society we see it at every level of sports: the “I” syndrome, the selfishness, the lack of respect for coaches and teammates. It’s the fiber that destroys any chance for success.

My guess is the banner will hang in our gym until someone in the school decides to replace the old one. Perhaps Jay’s children or grandchildren will want the old one to add to their family memorabilia. And after the new one is hung up and another forty years have passed, someone else will write a story about the banner that continues to hang in Mio’s gym.

NOTE: Jay Smith went on to play at Bowling Green and Saginaw Valley State University, and coach at Kent State, University of Michigan, Grand Valley State, Central Michigan, Detroit Mercy, and currently as head coach at Kalamazoo College. He was diagnosed with prostate cancer last summer and faces another round of radiation treatments after undergoing surgery in September. Click for a recent report by WOOD TV.

PHOTOS: (Top) The banner celebrating Jay Smith’s state high school career scoring record continues to greet fans at Mio High School’s gym. (Middle) Smith was a standout for the Thunderbolts through his graduation in 1979. (Below) Smith scored 2,841 points over four seasons, averaging 29 points per game.