Timeout to Appreciate Officials

September 23, 2013

By Kevin Wolma

Hudsonville athletic director

Wolma is in his third school year as athletic director at Hudsonville and previously coached basketball and golf. Below is a recent “30-second timeout” he wrote for the Hudsonville district newsletter.

We were five seconds away from one of the greatest upsets in the history of Caledonia basketball.

During the regular season, South Christian had beaten us by more than 30 points on two different occasions. The District Finals became the site for the third contest between the two schools on a warm March day.

We were able to slow them down just enough to stay within striking distance until late in the fourth quarter, when we finally took the lead for the first time. South Christian had one last chance with seven seconds left on the clock. After a timeout, they in-bounded the ball from the sideline and their player forced up a shot. I could see it was going to be short from my viewpoint, and my heart began to race with adrenaline as I could sense the impossible was going to become possible.

What happened next has stuck with me for the rest of my life, as one of the South Christian players pushed one of our players in the back, grabbed the rebound, and put the ball in the basket with one second left.

Game over. South Christian wins the District championship.

For the next eight years as a varsity basketball coach, I held a grudge against officials for that one call. Twelve years later, after I was done coaching, I went back and watched the game over again for the first time. I almost turned the video off when they in-bounded the ball in those last seven seconds because I did not want to relive that moment and the ensuing emotions that took place.

While watching I discovered something.

The South Christian player did not shove my player as much as I thought, and our players did not box out like I had thought, which made it easier for them to get the rebound and score. Looking back, did I even tell my players to box out during that last timeout before the ball was in-bounded?

At that moment it became very clear to me that what we see during a game may be clouded because we want our team to gain every advantage and every call in order for them to be successful. Perception is not reality. Officials are human. They will make mistakes just like the coaches and players do during a game.

There still has never been a game that has been decided by an official. Some people will say that the Class B Semifinal boys basketball game (in 2010) was decided on an official’s call when they ruled one of Forest Hills Northern’s player's foot was on the line on his last-second shot when in reality his foot clearly was behind the line. That call cost them a chance to play in the (MHSAA) Finals.

Coach Steve Harvey was quoted in the paper as saying, "We had opportunities to take care of the game before it even came down to that shot.” In the moment it seemed like that one play cost Forest Hills Northern the game, but there were over 50 possessions on offense and defense that preceded the play and potential outcome.

Having the opportunity to spend time with officials inside the locker room has made it very evident they are serious about their jobs and calling the best game they can. I have had requests from officials to have a monitor available to break down film an hour and a half before their contest begins to see strengths and weaknesses in their placement and mechanics from prior contests. I have had officials upset at halftime or after a game because they realized they made a mistake. I have had officials contact me personally after a game to apologize for a call made during the contest.

In the business world and also in education we use the word collaboration a lot. Officials collaborate before, during, and after every contest to garner more knowledge so they can continue to improve.

This is not even their full time job. Officials do what they do because they love the game and want to give back to the sport that made an impact on them.

The next time we are at a game and we think the officials missed a call, let’s take a 30-second timeout to gather our emotions so we do not say anything we will regret later. Instead let’s spend our energy cheering on our teams to be the best they can be.

Friday Nights Always Memorable as Record-Setter Essenburg Begins 52nd Year as Official

By

Steve Vedder

Special for MHSAA.com

August 31, 2023

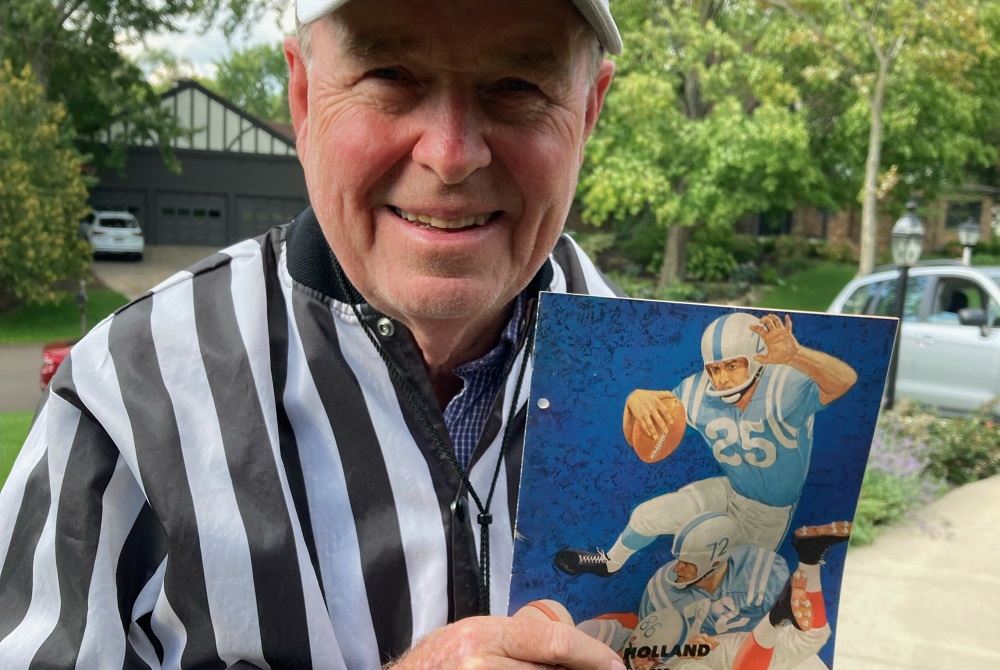

GRAND RAPIDS – All Tom Essenburg could think of was the warmth of a waiting bus.

Five decades later, that's what Essenburg – then a senior defensive back at Holland High School – remembers most about a stormy Friday night before 2,100 thoroughly drenched fans at Riverview Park. He recalls having a solid night from his position in the Dutch secondary. He remembers a fourth-quarter downpour, Holland eventually winning the game and trudging wearily through the lakes of mud to the team's bus.

But what never dawned on Essenburg until much later was that he had been the first to accomplish something only three defenders in the history of Michigan high school football have ever done:

Intercept five passes in a single game.

"I knew after the game that I had a bunch of them, but (at the time) we were in a 0-0 game and my mind was on just don't get beat (on a pass) and we lose 7-0," he said of the Sept. 21, 1962, contest against Muskegon Heights.

It wasn't until the next morning's story in the Holland Evening Sentinel that Essenburg grasped what exactly had happened. He didn't realize until then that he had picked off five passes in all, including two over the last 1:52 that sealed a 12-0 win over Muskegon Heights. One of the interceptions went for a 37-yard touchdown, which Essenburg does vividly remember.

"I remember thinking to myself that I had to score," said Essenburg, who has been involved with high school sports in one fashion or another for more than 60 years. "There was a Muskegon Heights guy who had the angle on me and I pretty much thought I was going to get tackled, but I got in there."

Essenburg's recollection of the first three interceptions is a bit hazy after 61 years, but the next day's newspaper account pointed out one amazing fact. The Muskegon Heights quarterback had only attempted six passes during the entire game, with five of them winding up in the hands of the 5-foot-8, 155-pound Essenburg – who had never intercepted a single pass before that night. He would later intercept two more in the season finale against Grand Rapids Central.

It wasn't until the middle 1970s that Essenburg began wondering where the five-interception performance ranked among Michigan High School Athletic Association records. What he remembers most about the game was the overwhelming desire to find warmth and dry out.

"I just wanted to get to the bus and get warm. We were all soaked," he said. "For me it was like, 'OK, game over.' I was just part of the story."

Curiosity, however, eventually got the better of Essenburg. A decade later he contacted legendary MHSAA historian Dick Kishpaugh, who in an attempt to confirm the five interceptions, wrote to Muskegon Heights coach Okie Johnson, who quickly verified the mark.

It turns out that at the time in 1962, nobody had even intercepted four passes in a game. And since Essenburg's record night, only Tony Gill of Temperance Bedford on Oct. 13, 1990, and then Zach Brigham of Concord on Oct. 15, 2010, have matched intercepting five passes in one game.

Three years after Essenburg's special night, Dave Slaggert of Saginaw St. Peter & Paul became the first of 17 players to intercept four passes in a game.

Essenburg laughs about it now, but his five interceptions didn't even earn him Player of the Week honors from the local Holland Optimist Club. Instead, the club inexplicably gave the honor to a defensive lineman.

Essenburg laughs about it now, but his five interceptions didn't even earn him Player of the Week honors from the local Holland Optimist Club. Instead, the club inexplicably gave the honor to a defensive lineman.

It was that last interception Essenburg cherishes the most. His fourth with 1:52 remaining at the Holland 17-yard line had set up a seven-play, 83-yard drive that snapped a scoreless tie. Then on Muskegon Height's next possession, Essenburg grabbed an errant pass and raced 37 yards down the sideline to seal the game with 13 seconds left.

In those days, running games dominated high school football and defensive backs were left virtually on their own, Essenburg said.

"I kept thinking don't let them beat you, don't let them beat you. No one can get beyond you. In those days, once a receiver got in the secondary, they were gone," said Essenburg, who describes himself as a capable defender but no star.

"I wasn't great, but I guess I was pretty good for those days," he said. "I'm proud that I'm in the record book with a verified record."

Essenburg's Holland High School career, which also included varsity letters in tennis and baseball, is part of a lifelong association with prep sports. After playing tennis at Western Michigan, he became Allegan High School's athletic director in 1971 while coaching the tennis team and junior varsity football from 1967-73.

But he's most proud of being a member of the West Michigan Officials Association for the last 47 years. During that time, Essenburg estimates he's officiated more than 400 varsity football games and nearly 1,000 freshman and junior varsity contests. In all, he's worked 83 playoff games, including six MHSAA Finals, the most recent in 2020 at Ford Field. An MHSAA-registered official for 52 years total, he's also officiated high school softball since 1989.

Essenburg also worked collegiately in the Division III Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association and NAIA for 35 years, including officiating the 2005 Alonzo Stag Bowl.

Essenburg said the one thing that's kept him active in officiating is being a small part of the tight community and family bonds that make fall Friday nights special.

"I enjoy being part of high schools' Friday night environment," he said. "All that is so good to me, especially the playoffs. It's the small schools and being part of community. I used to say it was the smell of the grass, but now, of course, it's turf.

"I can't play anymore, but I can play a part in high school football in keeping the rules and being fair to both teams. That's what I want to be part of."

While it can be argued high school football now is a far cry from Essenburg's era, he believes his even-tempered attitude serves him well as an official. It's also the first advice he would pass along to young officials.

"My makeup is that I don't get rattled," he said. "Sure, I hear things, but does it rattle me? No. I look at it as part of the game. My goal is to be respected.

"I've never once ejected a coach. It's pretty much just trying to be cool and collected in talking to coaches. It's like, 'OK Coach, You've had your say, let's go on."

While Essenburg is rightly proud of his five-interception record, he believes the new days of quarterbacks throwing two dozen times in a game will eventually lead to his mark falling by the wayside. And that's fine, he said.

"It'll get beaten, no question. It's just a matter of when," he said. "Quarterbacks are so big now, like 6-4, 200 pounds, and they are strong-armed because of weight programs. They throw lots of passes now, so there's no doubt it's going to happen."

Until Essenburg is erased from the record book, he'll take his satisfaction from his connection with Friday Night Lights.

"I love high school sports and being with coaches and players," he said. "My goal was once to work for the FBI or be a high school coach, but now I want to continue working football games on Friday nights until someone says no more."

PHOTOS (Top) Tom Essenburg holds up a copy of the program from the 1962 game during which he intercepted a record five passes for Holland against Muskegon Heights. (Middle) Essenburg, left, and Al Noles officiate an Addix all-star game in Grand Rapids. (Photos courtesy of Tom Essenburg.)