Prepping for the Long Run

May 9, 2014

By Rob Kaminski

MHSAA benchmarks editor

Case studies of Middle Child Syndrome range far and wide in the world of family psychology. But at the center of most dialogue regarding those affected is a feeling of being ignored or left out.

Within the family tree of scholastic sports, however, there’s no better time to be in the middle, as the tween and early teen generation is commanding the MHSAA’s utmost attention.

While participation numbers for high school athletics continue to hold steady in Michigan, junior high/middle school membership in the MHSAA is on the decline. In just the last seven years, membership among the vital group has dropped by exactly 100 buildings, from 831 schools in 2005-06 to 731 this year. That figure represents just 36.5% of the nearly 2,000 schools in the 2013 Michigan Education Directory serving 7th- and 8th-graders.

The number of high schools comprising the MHSAA now is greater than that of the feeder schools, bewildering when considering that a large percentage of high schools draw students from at least two junior high/middle schools.

To reverse the trend, the first order of business is to identify reasons junior highs and middle schools are leaving the MHSAA, or in more numerous cases, not joining the association at the start.

Armed with data from the 2013 MHSAA Update Meeting Survey and positions advanced by the MHSAA Junior High/Middle School Committee, a task force has been formed to examine problems and recommend solutions.

“We didn’t have an overwhelming ‘Yes’ or ‘No,’ or definitive answers, through the Update Meeting Survey on the various junior high/middle school topics. There are so many models in existence throughout the state. Some have grades 5-8, some 6, 7 and 8, some K-12,” said MHSAA Representative Council member Karen Leinaar, explaining her motion at the December Council meeting that a task force be formed.

“We hope the task force can provide information and direction by putting different minds together to narrow down some action plans to encourage more junior high/middle school membership,” added Leinaar, athletic director at Bear Lake, a K-12 building.

“When you see the numbers, it makes you scratch your head and think, ‘What can we do to get that number to at least 50 percent,” said fellow Council member Jason Mellema, superintendent at Pewamo-Westphalia Schools. “I’d like the task force to approach schools which aren’t members currently and ask, ‘Why?’ Those responses will be valuable.”

At the heart of the matter are separate but parallel discussions aimed at making junior high/middle school membership more attractive. Implementing either of the two requires different measures of MHSAA protocol.

The first matter would require MHSAA Representative Council action. These issues pertain to lengths of contests and seasons at the middle school level. Lengthening seasons and/or contests could provide more ample playing time for schools which currently find it difficult to mete out opportunities for all students in the program.

The second consideration involves the inclusion of 6th-graders into school athletic programs. Such action would require an MHSAA Constitutional change which would be confirmed by a two-thirds favorable vote on a ballot authorized by the Representative Council.

Extending the arm of MHSAA membership to 6th-graders might enable smaller school districts to begin programs and teams where currently none exist due to low enrollments.

In communities of all sizes, 6th-grade participation could encourage students to join school teams at an earlier age, exposing them to the values and benefits of school-based sports vs. community sports in which many youngsters are already participating.

“AAU (Amateur Athletic Union) and community-based sports aren’t going away,” said MHSAA Council member Steve Newkirk, principal at Clare Middle School. “What is our rationale when we examine lengthening seasons or extending our role to include 6th-graders? If we’re jumping into this attempting to control something that we can’t control, that’s not the right reason. But, if we can increase participation in some schools which otherwise wouldn’t have programs, then we need to figure out how to do that.”

In a nutshell, the keys to increasing membership among the MHSAA’s younger students are speculative at this point.

There does seem to be growing consensus, however, that when a new model is unveiled, it will be up to local leadership to grab the keys and drive the vehicle down the right roads.

Matter of minutes

Like an older or younger sibling, “burnout” gets a lot of attention from sports study professionals as a significant reason many young people walk away from sports.

Too much, too soon. Too much specialization. Data certainly exists to support both.

Often overlooked is exclusion. Not getting enough playing time, not feeling like part of the team, practicing just as hard but only playing the meaningless “fifth quarter.”

The MHSAA sets forth season and contest limitations for both its senior high schools and junior high/middle schools.

Survey data illustrates that Michigan is more restrictive than some neighboring states, and there seems to be growing momentum among constituents to lengthen contests rather than seasons.

Survey data illustrates that Michigan is more restrictive than some neighboring states, and there seems to be growing momentum among constituents to lengthen contests rather than seasons.

“It’s interesting to see what some of the other states have in place, and in many instances we allow significantly fewer contests,” said Mellema. “Maybe increasing the number of contests would be the hook for increasing our membership.”

Michigan’s restrictions on the number of contests are a bit more stringent from others surveyed. However, the mood from January’s Junior High/Middle School Committee Meeting at the MHSAA, along with the flavor from last fall’s Update Meetings, seems to signify little desire for change.

When invested personnel were asked whether they would favor increased basketball and soccer schedules at the middle school level, the answer was ‘No,’ to the tune of 60 percent regarding basketball and 68 percent when it came to soccer.

“Our coaches want practice time, and increasing the number of games would actually take away from practice time,” said Kevin Polston, who heads the athletic department at a 7th-8th-grade building in Grand Haven. “Increasing the length of contests would be favored over playing more actual games.”

Early dismissal from school, increased transportation, contest officials and game management expenses also work against the notion of upping the number of events.

“When we talk about adding games, I see dollar signs,” said Blissfield’s Steve Babbitt. “More buses, more officials, more game management.”

Adding dates to schedules might also bring unwanted consequences to the school calendar.

“If we were to add contests, particularly in the fall, then the practice start dates might become an issue to get in the proper number of days before the season begins,” said Joe Alessandrini of Livonia. “We’d have to start practice before school begins.”

One problem inherent to late summer practice at the junior high/middle school level is that, unlike high school, many coaches use the first weeks of school simply to recruit kids to try out for their teams.

Gaining far greater momentum at the recent Committee Meeting was the advocacy for longer games through the addition of a couple minutes per quarter.

That position is further bolstered by the Update Meeting Survey, which revealed respondents’ favoring an increase in basketball quarters from six to 8 minutes, and for a “fifth quarter” in football to allow more students the opportunity to compete.

Just over half of the survey takers (52 to 48 percent) were more reluctant to add minutes to football quarters, but several JH/MS Committee Members point to longer football games as a key to participation. On many occasions, it was reported, football teams have run nearly all the time out of a quarter without the other team touching the ball. And, kids who only play the “fifth quarter” aren’t fooled by their roles if they only play when the game is over and nothing counts. Incorporating them into the flow of the game is preferred.

Others in the meeting discussed ways in which coaches rotated team units during a contest, and conference guidelines which have been established to promote participation while still allowing teams to be competitive at the ends of games.

Others in the meeting discussed ways in which coaches rotated team units during a contest, and conference guidelines which have been established to promote participation while still allowing teams to be competitive at the ends of games.

“My concern when looking at game times is that we need to be specific and put constraints on how many minutes or quarters kids can play. That becomes tricky,” said Mellema.

“I’d like to have this meeting recorded to show that our opinions are not isolated; that we all share the same views, values and issues throughout the state,” said Constantine’s Mike Messner during the January meeting.

And that’s where influence at the local level from experienced school leaders is paramount.

“Our good intentions sometimes are not carried out the way we meant for them to be,” Leinaar said. “We have to impress on our schools why these changes are taking place, if we change things like length of seasons or contests.

“If it’s about winning, adding eight or 10 minutes to each game won’t change anything. If we add games, we see it as increased opportunities for kids, but coaches might not use it that way.”

Former MHSAA Assistant Director Randy Allen, who presided over JH/MS Committee Meetings in recent years, added, “The details of this can never be carried out or achieved by the state association. We can provide a tool to help achieve the goal of increased participation, but our schools have to implement it to be effective.”

Pleading the 6th

Even altering season and contest limits won’t address participation issues if kids can’t play.

Enter the debate over welcoming 6th-graders into the scholastic sports mix, an even hotter and more divided topic than game and season duration.

Whereas support for amending the MHSAA Constitution once lingered just below level ground, the most recent Update Meeting Survey is creating a groundswell, if not yet of seismic proportions.

In 2008, 47.5 percent of member schools indicated a desire to include 6th-graders in the MHSAA Handbook. Last fall, that figure rose to 59.4 percent overall, and up to 61.1 percent for just those individuals responsible for 7th and 8th-grade students in their districts.

It is worth noting that in more nearly 80 percent of school districts which include MHSAA member schools, 6th-graders share the same building with 7th- and 8th-graders.

Let the opening arguments begin.

“We’re talking 60 percent who are in favor of amending the Constitution. That’s a significant number,” Mellema said. “For larger schools with good numbers and only 7th- and 8th-graders in the buildings, it’s not an issue. But some smaller schools wouldn’t have teams without 6th-graders.”

Yet, in most places, 6th-graders are playing anyway, just not wearing the school colors.

“Because there are so many outside groups that have keyed in on kids at such a young age, I think it’s time to reach out to the younger grades to maintain educational athletics,” said Leinaar. “Fewer kids are on the playgrounds. Parents have them scheduled for soccer, judo, piano, and anything else you can think of. So, we should take the opportunity to develop the team concept in an educational setting without the little league mom and dad coaches.”

There is sentiment that the work needs to be focused in-house, or in the hallways, with deference to non-school athletic opportunities.

“It’s not about competing with outside entities,” said Brian Swinehart, athletic director of Walled Lake schools. “It’s about providing the best experience for those who are in our schools; getting them more opportunity to play.”

And getting them to play with structured coaching regulations. Within the MHSAA, members are strongly encouraged to hire coaches who are employed by the school district. Non-faculty coaches are required to be listed on forms submitted to the MHSAA, and in the very near future, all MHSAA coaches will be required to complete Coaches Advancement Courses and courses in basic safety and first aid.

“I coach my son in AAU wrestling, and my eyes opened up when I found that anyone with $18 and a computer could be a coach,” Newkirk said. “Anyone under the sun can coach.

“We need to get to the root of what it is we’re trying to accomplish. Is our goal the opportunity to play school sports or is the undercurrent to impact AAU sports? Maybe there’s a way to work with the coaches who are coming into our buildings and collaborate with them to have them buy into our values and philosophies.”

Polston echoed those sentiments at the JH/MS Committee meeting.

“If adding 6th-graders is to further our competitive nature versus non-school activities, I don’t think we’re ever going to do well at that,” Polston said. “Their philosophy is to win, and ours is education and value based.”

Just as school-based athletics differ from outside organizations, there also can be marked differences in the lives of youths as they move from elementary to junior high and middle schools. Such social transition periods are also considered.

“We’re already asking kids to grow up way too fast,” said Newkirk, whose school in Clare is 5th-8th grade. “It used to be Hot Wheels, Barbie Dolls and G.I. Joes, and now it’s all cell phones and texting and dating. Adding sports to those dynamics might create just another source of stress.”

The counterpoint could spotlight the exclusion factor again.

“I’m in a 6th-8th-grade building, and there’s a void for 6th-graders,” said Alan Alsbro of Berrien Springs.

Messner reiterates concerns that 6th-grade sports might be too much, too soon at a pivotal age for students, and also mentions certain buzzwords that are like nails on a chalkboard to all levels of school sports leaders: finances and facilities.

Messner reiterates concerns that 6th-grade sports might be too much, too soon at a pivotal age for students, and also mentions certain buzzwords that are like nails on a chalkboard to all levels of school sports leaders: finances and facilities.

“We’re a 6-8 building, and we’ve always felt that the 6th-grade year is a year of adjustment academically and socially, so let’s start athletics in 7th grade,” Messner said. “And, we’ve already had to budget out freshman-level sports at the high school, so how can we justify 6th-grade? We’re not going to find a pot of money.”

Cash will always be a concern for school programs, but the facilities and transportation arguments are quickly debunked by some.

“We have 5th- and 6th-grade teams that are school-based right now. We don’t pay the coaches, don’t collect participation fees or take physicals, but they do use our facilities, and we find room and time in the schedule,” Mellema said.

“Some schools treat the lower grades as intramurals, still hosting the events in their facilities, so it can be done if we expand our programs down a grade,” Leinaar said. “People say, ‘Oh that’d be a lot of work.’ Yeah. It would, but you just have to figure out a way to do it.”

The facility and finance issue could, in fact, be a moot point. A change to the Constitution would not necessarily force schools to sponsor stand- alone 6th-grade teams. In fact, the change might not mandate schools include 6th-graders at all.

A change would simply provide the opportunity for participation. The underlying feeling within the JH/MS Committee was that local boards and conferences would determine the extent of 6th-grade participation.

“I think the fear of 6th-grade stand-alone teams could deter some districts from having their middle schools join the MHSAA,” said Sean Zaborowski of St. Clair Shores. “It’s not viable to have 6th-grade-only football teams, basketball teams, etc. The question becomes whether to allow them to participate with 7th-and 8th-graders.”

For some, it might simply be a question of need, on a sport-by-sport basis.

“We have enough numbers that we don’t need 6th-graders to fill out rosters,” said Muskegon’s Todd Farmer of his 7-8 building. “Only the cross country people are asking about it. And, if we allow 6th-graders to participate, then do we allow 7th-graders to play with 8th-graders?”

That is another piece to the puzzle with which administrators are wrestling, in some cases quite literally.

Contact list

Wrestling is one of the sports most in need of 6th-grade participants, if for nothing more than filling the lightest weight classes.

The Update Meeting Survey showed nearly 42 percent in favor of 6th-graders competing with 7th- and 8th-graders in wrestling. Among “contact” sports, only basketball received slightly more support at 52 percent.

“Non-contact sports is where the focus should be,” Alsbro said. “In the non-contact sports, I think it’s a no-brainer to get students exposed to competition without getting their brains knocked out.”

The fall survey backs that sentiment with support as high as 73 percent in cross country and 67 percent in track & field. Football, ice hockey and lacrosse yield percentages of 72 or above opposed to 6th-graders playing with 7th- and 8th-graders.

Leinaar speculates that it might be time to include 6th-graders in all “non-combative” sports.

Leinaar speculates that it might be time to include 6th-graders in all “non-combative” sports.

Wrestling certainly falls in the contact category, but it is individual in nature. The JH/MS Committee suggested that the MHSAA Task Force consider the merits of team vs. individual sports as the natural division as to the inclusion of 6th-graders on the same teams as their 7th- and 8th-grade classmates.

Recent MHSAA waiver requests indicate a movement for such action to be taken. Consider the following:

- During the 2011-12 school year, 40 school districts made requests to the MHSAA Executive Committee to waive Regulation III, Section 1, pursuant to what is now Interpretation 262 so that 6th-graders could compete with and against 7th- and 8th-graders. The Executive Committee approved 37 of those requests.

- During the 2012-13 school year, 50 school districts made this request to allow 6th-graders on 7th- and 8th-grade teams, and 46 requests were approved.

The majority of these requests came in the sports of basketball, cross country, and track & field. On several occasions, schools were granted permission in all sports other than football, ice hockey and wrestling.

Interpretation 262 also states that requests may be submitted by the administration of “smaller member junior high/middle schools.” This might have deterred some districts from seeking 6th-grade participation and, in turn, eliminated the possibility of fielding a team in some cases.

In light of such history and language, the JH/MS Committee asked to forward the following positions to the Task Force and beyond:

- Change the current 6th-grade waiver process to allow schools of any enrollment size to be considered for waivers on a case-by-case basis that is need-specific, not granted only to small enrollment schools.

- Eliminate the waiver requirement for 6th-grade participation in individual sports, and maintain the waiver process and criteria for team sports.

Even with a Constitutional amendment to include 6th-graders in programs statewide, decisions would have to be made locally as to which teams they may be a part.

Outside the hallways

In addition to the primary topics of season and contest limitations and 6th-grade participation, the JH/MS Committee was asked for suggestions on how the MHSAA could retain current JH/MS members and make membership more attractive to schools not currently members. The following thoughts were expressed for consideration:

- Make membership required for those junior high/middle schools of MHSAA senior high schools. In other words, require district-wide membership (fully recognizing the difficulty with private school members).

- Provide MHSAA CAP courses at no charge or at a greatly reduced cost to JH/MS members.

- Modify the Limited Team Membership Rule at grades 7-8 to allow some participation in the same sport with non-school programs during the school season. Such allowance would have restrictions, to be determined.

- Give member schools flexibility on the start of fall football practices.

- Allow more local league and conference decision-making within broad statewide MHSAA regulations.

This input from the JH/MS Committee will be an important voice in the deliberations of the JH/MS Task Force that will convene multiple times during 2014 to bring a breadth and depth of study unprecedented on this topic in the MHSAA’s long history.

The quest for increased membership among the state’s junior high/middle schools – and thus, increased participation within the framework of educational athletics – is of utmost importance to the health and future of high school athletics.

Quoting MHSAA Executive Director Jack Roberts from his blog Oct. 8 on MHSAA.com, “School sports needs to market itself better, and part of better is to be available earlier – much sooner in the lives of youth.”

It is an age group that can no longer be ignored, or take a back seat to its older brothers and sisters.

Retired Official Gives Alpena AD New Life with Donated Kidney - 'Something I Had to Do'

By

Geoff Kimmerly

MHSAA.com senior editor

May 3, 2024

TAWAS CITY – Jon Studley woke up Feb. 20 with a lot of fond memories on his mind, which turned into a collection of 47 photos posted to Facebook showing how he’d lived a fuller life over the past year with Dan Godwin’s kidney helping power his body.

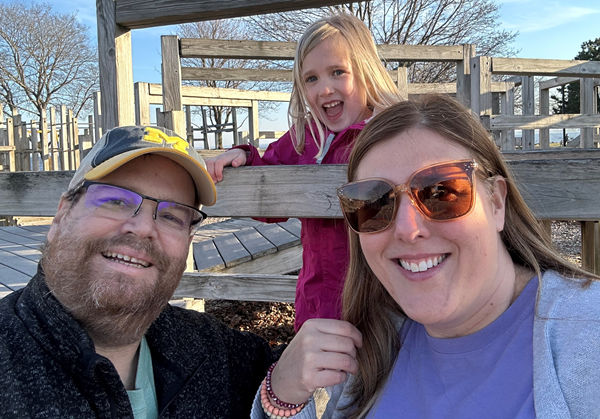

There was Studley at the beach, taking a sunset shot with wife Shannon and their 5-year-old daughter Maizy. In others Dad and daughter are at the ice rink, making breakfast and hitting pitches in the yard. Studley made it to Ford Field to cheer on the Lions, supported his Alpena High athletes at MHSAA Finals and traveled to Orlando for a national athletic directors conference.

Their faces are beaming, a far cry from much of 2021 and 2022 and the first few months of 2023 as the Studleys and Godwins built up to a weekend in Cleveland that recharged Jon’s body and at least extended his life, if not saved it altogether.

“People that saw me before transplant, they thought I was dying,” Studley recalled Feb. 21 as he and Godwin met to retell their story over a long lunch in Tawas. “That’s how bad I looked.

“(I’m) thankful that Dan was willing to do this. Because if he didn’t, I don’t know what would’ve happened.”

By his own admission, Studley will never be able to thank Godwin enough for making all of this possible. But more on that later.

Studley and Godwin – a retired probation officer and high school sports official – hope their transplant journey together over the last 23 months inspires someone to consider becoming a donor as well.

For Studley, the motivation is obvious. Amid two years of nightly 10-hour dialysis cycles, and the final six months with his quality of life dipping significantly, Studley knew a kidney transplant would be the only way he’d be able to reclaim an active lifestyle. And it’s worked, perhaps better than either he or Godwin imagined was possible.

For Godwin, the reasons are a little different – and admittedly a bit unanticipated. He’d known Studley mostly from refereeing basketball games where Studley had served as an athletic director. He’d always appreciated how Studley took care of him and his crew when they worked at his school. But while that was pretty much the extent of their previous relationship, some details of Studley’s story and similarities to his own really struck Godwin – and led him to make their lifelong connection.

“It’s been rewarding for me. I have told Jon, and I’ve said this to anyone who would listen, that I’m grateful and feel lucky that I’ve been part of this process,” Godwin said. “I don’t feel burdened. I don’t feel anything except a sense of appreciation to Jon that he took me on this journey. I didn’t expect that, but that’s how I feel.”

Making a connection

As of March, there were 103,223 people nationwide on the national organ transplant waiting list, with 89,101 – or more than 86 percent – hoping for a kidney, according to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). More than 46,000 transplants were performed in 2023, including the sharing of more than 27,000 kidneys.

Godwin giving one to Studley was among them.

Studley, 43, has served in school athletics for most of the last two decades since graduating with his bachelor’s degree from Central Michigan University. After previously serving as an assistant at Mount Pleasant Sacred Heart, he became the school’s athletic director at 2009. He moved to Caro in 2012, then to his alma mater Tawas in 2015 for a year before going to Ogemaw Heights. He then took over the Alpena athletic department at the start of the 2020-21 school year, during perhaps the most complicated time in Michigan school sports history as just months earlier the MHSAA was forced to cancel the 2020 spring season because of COVID-19.

He's respected and appreciated both locally and statewide, and was named his region’s Athletic Director of the Year for 2019-20 by the Michigan Interscholastic Athletic Administrators Association. Concurrently with serving at Sacred Heart and earning his master’s at CMU, Studley served as athletic director of Mid Michigan College as that school brought back athletics in 2010 for the first time in three decades. He also served four years on the Tawas City Council during his time at Tawas High and Ogemaw Heights.

Toward the end of his senior year of high school in 2001, Studley was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. For the next two decades, he managed his diabetes primarily with insulin and other medication. But during that first year at Alpena, his health began to take a turn. Studley had been diagnosed with a heart condition – non-compaction cardiomyopathy – which led him to Cleveland Clinic for testing. A urine test in Cleveland indicated his kidneys might not be working like they should – which led to a trip to a specialist and eventually the diagnosis of kidney failure and the start of dialysis, with a kidney transplant inevitable.

Toward the end of his senior year of high school in 2001, Studley was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes. For the next two decades, he managed his diabetes primarily with insulin and other medication. But during that first year at Alpena, his health began to take a turn. Studley had been diagnosed with a heart condition – non-compaction cardiomyopathy – which led him to Cleveland Clinic for testing. A urine test in Cleveland indicated his kidneys might not be working like they should – which led to a trip to a specialist and eventually the diagnosis of kidney failure and the start of dialysis, with a kidney transplant inevitable.

Dialysis long has been a standard treatment for people with kidney issues. But it can take a toll. In Studley’s case, that meant being tired all the time – to the point of falling asleep at his desk or having to pull over while driving. He wasn’t receiving enough nutrients and was unable to lift things because of the port for the dialysis tube. Extra fluid building up that his body wouldn’t flush made him constantly uncomfortable.

The next step was transplant, and in July 2021 he was approved to receive a kidney.

The Studleys thought they had a prospect early on, as an aunt on Shannon’s side was a candidate for a paired match – her blood and tissue types weren’t a match for Studley, but matched another person on the waiting list whose donor would be a candidate to give Studley a kidney. But that didn’t work out.

Others showed interest and asked about the process, especially after Studley’s 20-year class reunion in 2021, but nothing concrete came about. Amid the early disappointment, Studley took some time to consider his next move – and then put out a plea over Facebook that fall to his close to 1,000 connections hoping that someone, anyone, might consider.

“I took a week to really think about it – this is what I’m asking for someone to do. I had to get over it in my mind that it was OK to ask,” Studley said. “I’m going to ask someone to make a sacrifice for me, and that’s not me. I always want to help everybody else.”

Godwin is that way too. And immediately after reading Studley’s post, he knew he needed to consider making a call.

Strong match

Godwin had moved to Tawas City from Midland in 2014, and after a few years off from officiating decided to get back on the court that following winter.

He thinks he and Studley may have crossed paths at some point during Studley’s tenures at Sacred Heart and Caro, but it was at Tawas where they got to know each other. Although Studley stayed at Tawas just one school year, Godwin continued officiating for him at Ogemaw Heights – and in fact, Godwin’s final game in 2018 was there, during the District basketball tournament. That night, during the first quarter, Godwin tore the plantar fasciitis in his left foot. He didn’t know if he’d be able to finish the game – the officials from the first game that night stuck around to step in just in case – but thanks in part to Studley connecting Godwin with the Alpena trainer during halftime, he was able to get through the final two quarters and finish his officiating career on his feet.

They’d become Facebook “friends” at some point, so Godwin had seen Studley’s posts over the years with Shannon and Maizy. And when he saw Studley ask for help, something hit him – “immediately.”

“I have a 5-year-old granddaughter, almost exactly the same age as Jon’s, and I’m the dad of one child, a daughter, so there were those connections,” Godwin said. “It almost didn’t feel like there was a choice. It felt like it was something I had to do.”

“I have a 5-year-old granddaughter, almost exactly the same age as Jon’s, and I’m the dad of one child, a daughter, so there were those connections,” Godwin said. “It almost didn’t feel like there was a choice. It felt like it was something I had to do.”

Godwin is 66 and always has been in good health. He’s also always been an organ donor on his driver's license and given blood, things like that. But he had never considered sharing an organ as a living donor until reading Studley’s post.

He read it again to his wife Laurie. They talked it over. He explained why he felt strongly about donating, even to someone he didn’t know that well. After some expected initial fears, Laurie was in. Their daughter had the same fears – What about the slight chance something could go wrong? – but told Laurie she knew neither of them would be able to change her dad’s mind.

“It took me a while to get on board with it, even though I knew in the vast majority of cases somebody who donates an organ is going to be absolutely fine. It’s still major surgery,” Laurie said. “I guess he was just feeling so much like it was something he wanted to do, and he is a very healthy physically fit person. So I felt the odds were really good that he was going to be fine.

“And really, probably, the deciding factor was Maizy. We have a granddaughter the same age, so we were just thinking she needs a dad.”

After a few more days of contemplation, Dan called Cleveland Clinic to find out how to get started.

Then he texted Studley.

“I was nervous saying yes. At first, I didn’t know what to say – I just kept saying, ‘You don’t have to do this, but I appreciate it,’” Studley said. “I never want to have somebody do something for me unless (the situation is dire) … so I told him thank you and I appreciate it, and no pressure.”

Generally, Studley said, the donor and recipient don’t receive information on how the other person is progressing through the process. Godwin, however, kept Studley in the loop, which was a good thing. “But then you’re wondering if it’s going to happen,” Studley said, “if it’s truly a match.”

The initial blood test showed that Godwin wasn’t just a match, but a “strong” match, meaning they share a blood type – the rarest, in fact – and Godwin also didn’t have the worrisome antibodies that could’ve caused his kidney to refuse becoming part of Studley’s body.

That was amazing news. But just the start. “There was so much more we had to go through just to get to surgery day,” Studley said.

Long road ahead

Studley relates the transplant process to a job interview. After meeting with a potential boss, the candidate must wait for an answer – and it could come the next day, or the next week, or months later.

There were several more tests for both to take to make sure the transplant had not only a strong enough chance of being successful, but also wouldn’t be harmful for either of them.

“Right up until the time of the donation, (things) can happen. Like they did blood work on me the Friday before the kidney transplant on Monday, and if that had showed something they were going to send me home,” Godwin said. “So I just kept thinking, is this going to work? It seemed that there were more things that could go wrong than the possibility that it could go right. And that sets everybody up for disappointment – me, because I was invested in doing it, and of course Jon and his family because it was important to them.”

Godwin made a trip to Cleveland Clinic in November – about three months before the surgery. It wasn’t a great visit. His electrocardiogram showed a concern, and a few suspicious skin lesions were an issue because donors must be cancer-free. Almost worse, he couldn’t get in for a follow-up appointment for six weeks.

The wait felt longer knowing not only that there was a possibility for disappointment for Studley, but also the potential something could be unwell with Godwin. But then came good news – at his follow-up, Godwin aced his stress test, alleviating any heart concerns, and the dermatologist said the lesions were basal cell carcinoma and not considered risky to the transplant.

Over the next three months, both Godwin and Studley continued to do whatever they could to keep the transplant on track. To avoid COVID, Godwin and his wife isolated as much as they could, and Studley began wearing a mask frequently at work. Godwin cut out alcohol and coffee and began walking regularly to keep in tip-top shape.

In January 2023, both got the final OK, and the surgery was scheduled for Feb. 20.

But that wasn’t the end of the anxiety.

Studley also had undergone a series of tests and doctor visits, and two days before the transplant he had to get a tooth removed to avoid a possible infection.

Then, on the way from Alpena to Cleveland, Studley’s vehicle hit a deer.

“How is this going to go now?” he recalled thinking. “This is how it started. What’s going to happen now?”

Both arrived in Cleveland safely, eventually. The families stayed apart all weekend, Studley and Godwin communicating briefly by text to check in. There were a few more stop-and-go moments. Godwin’s Friday blood work showed something unfamiliar that ended up harmless. On the day of the surgery, Studley was wheeled to just outside the operating room – and then taken back to his hospital room for another 15 minutes of suspense. Once Studley made it into the operating room, his doctors had to pause during the surgery to tend to an emergency.

But finally, the transplant was complete. And seemingly meant to be. Godwin’s kidney was producing urine for Studley’s body before the surgeons had finished closing him up.

Back on his feet

Studley said he knew he’d be fine once he could start walking the hallways at the hospital; he started doing so the next morning. Later that same day after transplant, on the way back from one of those walks, he saw Godwin for the first time since they’d both arrived in Cleveland. “It was absolutely emotional,” Godwin said.

Godwin went home four days after the surgery. Studley stayed the next month with appointments and labs twice a week. Shannon remained with him the first week, then friends Mike Baldwin and Josh Renkly and Studley’s father Larry took turns as roommates for a week apiece.

For the first three months, including his first two back in Alpena, Studley couldn’t go anywhere except for the trip to Cleveland every other week – which has now turned into every other month with virtual appointments the months in between. Total he missed about six months of work – and thanked especially assistant athletic director and hockey coach Ben Henry for shouldering the load in his absence.

Studley’s checkups are full of more good news. His body is showing no signs of rejecting the kidney. And as long as he keeps his diabetes under control, that shouldn’t affect his new organ either.

Shannon sees the difference while comparing a pair of family trips. The Studleys went to Disney World while Jon was on dialysis, and she said he made it through but got home just “depleted.” This past spring break, the family went to Gatlinburg, Tenn., and Jon had visibly more energy for hiking and other activities. The last six months of dialysis, Jon was sleeping a lot, but this spring he’s helping coach Maizy’s T-ball team and overall is able to spend more quality time with her.

“Most of (Maizy’s) life she’s only known him as sick Dad,” said Shannon, a counselor at Alpena’s Thunder Bay Junior High. “He wasn’t able to do a lot of things with her, and I’ve seen a lot more of that, and I think she notices.”

Jon will be taking anti-rejection medicine and a steroid every 12 hours for the rest of his life, but that and some other little life adjustments are more than worth it. All anyone has to do is look at those 47 photos from the Facebook post to understand why.

Jon will be taking anti-rejection medicine and a steroid every 12 hours for the rest of his life, but that and some other little life adjustments are more than worth it. All anyone has to do is look at those 47 photos from the Facebook post to understand why.

Godwin said he feels better now than he did even before surgery. He does his checkups with Cleveland Clinic over the phone. He also said that if Studley had been found at some point late in the process to be unable to except the kidney, Godwin still would’ve given it to someone else on the waiting list. “I was so invested at that point,” Godwin remembered. “That kidney was going.”

The two families got together for a reunion in August in Tawas, where they had lunch and walked the pier and the Godwins met Maizy for the first time. She doesn’t really get what’s transpired, but definitely notices Dad doesn’t have a tube coming out of his body at night anymore.

And it’s clear the two men value the connection they’ve made through this unlikely set of circumstances.

“His attitude has been inspiring,” Godwin said. “Because you’ve been through the mill (and) I’ve never heard a negative thing, ‘poor me’ or anything. And I think maybe that’s what helps keep you going.”

“You talk to people who know Dan, and they said, ‘That’s Dan. That’s what Dan does,’” Studley said, speaking of Godwin’s gift and then addressing him directly. “The hardest part for me, the biggest struggle … is there’s no way I’m going to ever be able to thank you for this.

“It’s like the post I posted yesterday on Facebook. I posted pictures of everything I had done in the last year, and a lot of it was stuff that I hadn’t done in a long time. My way to thank Dan is just living my life the best I can, enjoying my family. … For me, it’s changed my perspective.”

As lunch finished up, Godwin did have one ask in return – not for one of Studley’s organs, but to be part of a special moment that helped drive him to donate 12 months earlier.

“This isn’t the venue, but I’ve thought about this a lot. I’ve never asked for anything and I don’t want anything,” Godwin said, “but I would like to go to Maizy’s wedding.”

“Yeah, you … yes. Yes,” Studley replied. “You can go to anything you want to go to with my family.”

“I’d like to be there.”

“You will definitely be there.”

“I was at my daughter’s wedding,” Godwin said, noting again that connection between the men’s families, and the importance he felt in Studley being there for Maizy like he’d been there for his child.

“You say that, but there were times I didn’t know if I’d make it to Maizy’s wedding. I might not make it to see her graduate. So …” Studley trailed off, ready to take the next step in his life rejuvenated.

Studley emphasized the continuing need for kidney donors and refers anyone interested in learning more to the National Kidney Registry.

PHOTOS (Top) Alpena athletic director Jon Studley, left, and retired MHSAA game official Dan Godwin take a photo together on the shore of Lake Huron one year after Godwin donated a kidney to Studley. (2) Studley cheers on Alpena athletes during last season’s MHSAA Track & Field Finals at Rockford High School. (3) Godwin and Studley meet for the first time after the transplant, and again six months later. (4) Studley, his wife Shannon and daughter Maizy enjoy a moment after Jon had returned to good health. (Top photo by Geoff Kimmerly; other photos provided by Jon Studley.)