Hornets' Sorg Soars as Top Coach, Official

October 2, 2015

By Geoff Kimmerly

Second Half editor

WILLIAMSTON – Brent Sorg was a high school sophomore, on crutches a few weeks after knee surgery, when he stepped in to officiate a Lansing area 30-and-over men’s league soccer game although he couldn’t move more than a few feet from his post at midfield.

A dozen years later, Sorg ran matches at the highest U.S. level as one of 24 Major League Soccer referees during the 2004 and 2005 seasons.

That he remains one of the country's elite officials after rising so quickly is a story worth telling on its own – but only half of the 40-year-old's remarkable climb on the pitch.

That he remains one of the country's elite officials after rising so quickly is a story worth telling on its own – but only half of the 40-year-old's remarkable climb on the pitch.

Sorg is better known in Michigan high school soccer as the boys coach at Williamston, which he led to the MHSAA Division 3 Final last fall for the second time in three seasons.

That's quite a combination; in fact, he knows of only one other high-level official, from North Carolina, who coaches a high school team as well. But here's the kicker, pun intended: Sorg, a three-sport athlete in high school, never played a competitive soccer game past the eighth grade.

“It is sort of interesting to reflect on the path of how I’ve gotten there,” Sorg admitted during a Williamston practice last week. “The continuing education piece, surrounding yourself with good people, being willing to try things; that’s why I think I’ve been able to have some success. You don’t always do the cookie cutter approach. The game is very simple, but there’s always more than one way to go about it.”

He’s proof – although surely there are common strands tying together his officiating, coaching and day job success.

Soccer has become Sorg's passion. That, and sharp time management skills, play large parts in his pulling off coaching a contending high school team plus officiating high-level matches during free weekends, when he’s not working 8:30 p.m. – 6:30 a.m. most days protecting the capital city.

All in all, it’s been an eventful 365 days for the Hornets’ leader, who in addition to taking his team back to a championship game also officiated an NCAA Men’s Tournament Quarterfinal and a Women’s Semifinal, and was promoted to sergeant for the Lansing Police Department.

“He works hard at both (soccer) professions and continues to learn,” said Eaton Rapids coach Matt Boersma, a friend and colleague who has worked with Sorg on the board of the Michigan High School Soccer Coaches Association. “Brent is a great example of hard work. He has put it in in all three of his professions – cop, coach and ref – and has seen that hard work give great returns."

Starting down the path

Sorg did play under a legendary coach at East Lansing, but not five-time boys soccer champion Nick Archer.

Instead, he played junior varsity for the football program led by Jeff Smith, who won one MHSAA title and led the Trojans to two runner-up finishes during his multiple-decade tenure. Sorg also played basketball and baseball – but after tearing a right knee ligament as a sophomore, decided he was done as a high school athlete. He knew then he wanted to become a police officer and wanted to guard his knee for that future.

Sorg’s soccer playing career had ended a few years before; admittedly, he probably wasn’t good enough to play past junior high. But he had friends on East Lansing’s team and became a regular cheering them on – while he also became a regular on the pitch in another capacity.

He officiated his first games as a sixth grader at the request of his club coach, who needed someone to handle littler kids' matches at $6 apiece. That seemed like a pretty good deal. At 16 and 17, Sorg started making a few hundred dollars a weekend at youth tournaments and was part of the MHSAA Legacy Program. He later was mentored by Lansing’s Dean Kimmith in soccer and Rick Hammond for football and basketball, registering to officiate all three sports.

Sorg’s first coaching opportunity came from the same source. He graduated from East Lansing in 1994 and went on to Michigan State University, and a few years in his former club team needed a youth coach. Sorg and a buddy decided to give it a shot – and Sorg found another calling.

He stuck with coaching, moved up on the club scene, did the course work to earn his National "B" coaching license from the United States Soccer Federation, and then coached a season of junior varsity at Haslett in 2000. He also continued to officiate – he’s worked six MHSAA Finals in boys or girls socccer – eventually climbing the college ranks as well and earning his National Referee badge in 2002 on his way to MLS.

He stuck with coaching, moved up on the club scene, did the course work to earn his National "B" coaching license from the United States Soccer Federation, and then coached a season of junior varsity at Haslett in 2000. He also continued to officiate – he’s worked six MHSAA Finals in boys or girls socccer – eventually climbing the college ranks as well and earning his National Referee badge in 2002 on his way to MLS.

Sorg may referee only a dozen or so games in this season, depending on what his schedule allows. For example: He officiated at Virginia Tech on Sept. 27, landed in Detroit at midnight and finally made it to bed at 2 a.m. before starting his coaching and working life again the next day. Work duties eliminated the next two weekends from his officiating calendar.

But when available, Sorg gets games in the Big Ten, Atlantic Coast Conference, Horizon League and American Athletic Conference, and handled the NCAA Division III Men’s Final in 2013.

“Brent is a great referee. I can't remember if I've ever had a complaint about him,” said Steve Siomos, who assigns officials for the Big Ten and Horizon League among others. “The only thing that held him back to go to the top was his job and his coaching high school kids. Those were the two priorities; referee(ing) was after that.”

Building the program

Josh Ward is the second from his family to play for Sorg. He followed his brother Jake, joining the Williamston varsity for the 2012 playoff run.

Josh knew the Hornets' program probably more than most newcomers, but still chuckled to himself the first time he heard Sorg’s annual start to fall practice.

“He loves this program. One of his quotes at the beginning of every soccer season is that this is the best soccer program to play for, I think he says, in the world,” Ward said. “So he loves this place.”

It’s true.

“I’m pretty honored by it. I say that every day,” Sorg said. “I’m in a pretty good position, with an athletic director and staff that does a nice job supporting us and what we do. We’re pretty lucky.

“(And) we’re so lucky to have people who care about their community and schools. I get comments all the time how our practice fields are better than some game fields.”

Sorg was hired in 2005, with just his club experience and that one year of JV coaching to his credit. The Williamston program had been average most seasons, but with potential for more backed also by an excited parent base that has since contributed to the building of a stadium used for multiple MHSAA Finals.

Whatever coaching skills Sorg missed out on by not playing, he’s apparently learned. The Hornets were 18-3-2 and won their first district title his first season, and have finished under .500 only once during his tenure. The 2012 team was 19-8-1 and lost the MHSAA Division 3 Final 1-0 in overtime to Grand Rapids South Christian. Last year’s team finished 13-4-6 and fell 1-0 to Hudsonville Unity Christian in the Final. This fall, Williamston is 12-3 and ranked No. 3 in Division 3, despite a schedule featuring teams currently ranked in all four divisions, including Division 3 No. 1 Flint Powers Catholic, Division 4 No. 1 Lansing Christian and Mason, formerly No. 1 in Division 2.

Sorg has learned much by watching and listening – be it at local, state and national coaching conferences, or when he’s on the sideline as an official waiting for his college games to start. Boersma noted that Sorg is a regular at the National Soccer Coaches Association of America convention, and the Hornets’ pregame warm-up includes a drill Sorg picked up reffing Wake Forest. He's also absorbed what he could mixing with longtime mid-Michigan coaches like Archer, retired Eaton Rapids coach Joe Honsowitz, recently-retired Jamal Mubarakeh of DeWitt and Hornets girls coach Jim Flore.

Sorg has learned much by watching and listening – be it at local, state and national coaching conferences, or when he’s on the sideline as an official waiting for his college games to start. Boersma noted that Sorg is a regular at the National Soccer Coaches Association of America convention, and the Hornets’ pregame warm-up includes a drill Sorg picked up reffing Wake Forest. He's also absorbed what he could mixing with longtime mid-Michigan coaches like Archer, retired Eaton Rapids coach Joe Honsowitz, recently-retired Jamal Mubarakeh of DeWitt and Hornets girls coach Jim Flore.

Sorg also has surrounded himself with experience, including assistant Steve Horn, who transformed Lansing Everett into a Division 1 power from 2005-11. Williamston’s 2012 goalkeeper, Charlie Coon, works with the current goalies, and junior varsity coaches Jason Davis and Bruce Collopy have been involved with the program for years as well.

Discipline is a staple, as one might guess with a police officer as coach – although the drive to do things right and to completion was nurtured by parents Rich and Pat, who moved the family to Michigan from Texas when Brent was 10. “It’s about … how you carry yourself. You have to work for it. That’s such an emphasis for me and the program," Brent said.

Ward said his coach finds a balance between making practices fun and competitive – “which is kinda hard to do,” Ward said.

When a player snuck in a cell phone during the team’s preseason overnight camp, Sorg made him carry each of his teammates the length of the field – something more memorable for the entire team that simply making the rule-breaker run alone.

“And at the end of the day, for me, it’s not always about the soccer component, but developing young men. Making them into good human beings and good citizens,” Sorg said.

Right on time

As Sorg was climbing the officiating ranks, Mason coach Nick Binder was rising as a player, starring first for the Bulldogs before moving on to MSU from 1999-2003. Sorg worked Binder’s youth, high school and college games, and the two now meet as leaders of elite Capital Area Activities Conference programs.

“It’s very cool to see a local guy on TV officiating the highest level of professional soccer in our country,” Binder said. “(And) as a coach, I have the utmost respect for what he’s done at Williamston over the last decade in which we’ve both been coaching. His attention to detail and motivation to elevate Williamston among the area and state’s elite programs is evident, even from the outside. His schedule is always loaded with strong competition with a clear purpose to be battle-tested when the state tournament begins.”

Sorg does indeed load up the schedule to make sure his teams are prepared. The never-stop-learning approach was another trait passed on by his parents, and Sorg practices it in a variety of ways, be it reading up on the psychological component of a game or comparing notes on motivation with peers like Lansing Sexton football coach Dan Boggan, who took the Big Reds to the Division 4 Football Final last fall.

Former Waverly and Haslett soccer coach Jack Vogel told Sorg early on that it would take five years for Sorg to establish his program and 10 to get everything the way he wanted it.

This is season 11 for Sorg's Hornets. There’s no question he’s reached a desired coaching destination in addition to his lofty standing wearing the official’s shirt.

“When I reflect on that, it’s exactly what it is,” said Sorg of Vogel’s advice. “There’s no doubt that it’s happened.

“I think we’ve done a lot of good things here. I’m proud of what we’ve built.”

Geoff Kimmerly joined the MHSAA as its Media & Content Coordinator in Sept. 2011 after 12 years as Prep Sports Editor of the Lansing State Journal. He has served as Editor of Second Half since its creation in Jan. 2012. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for the Barry, Eaton, Ingham, Livingston, Ionia, Clinton, Shiawassee, Gratiot, Isabella, Clare and Montcalm counties.

Geoff Kimmerly joined the MHSAA as its Media & Content Coordinator in Sept. 2011 after 12 years as Prep Sports Editor of the Lansing State Journal. He has served as Editor of Second Half since its creation in Jan. 2012. Contact him at [email protected] with story ideas for the Barry, Eaton, Ingham, Livingston, Ionia, Clinton, Shiawassee, Gratiot, Isabella, Clare and Montcalm counties.

PHOTOS: (Top) Williamston boys soccer coach Brent Sorg, left, shares hands with Hudsonville Unity Christian's Randy Heethuis after last season's Division 3 Final. (Middle) Sorg has been a college official for 15 seasons, including during this ACC championship game. (Below) Sorg comforts one of his players after the Division 3 Final loss.

Friday Nights Always Memorable as Record-Setter Essenburg Begins 52nd Year as Official

By

Steve Vedder

Special for MHSAA.com

August 31, 2023

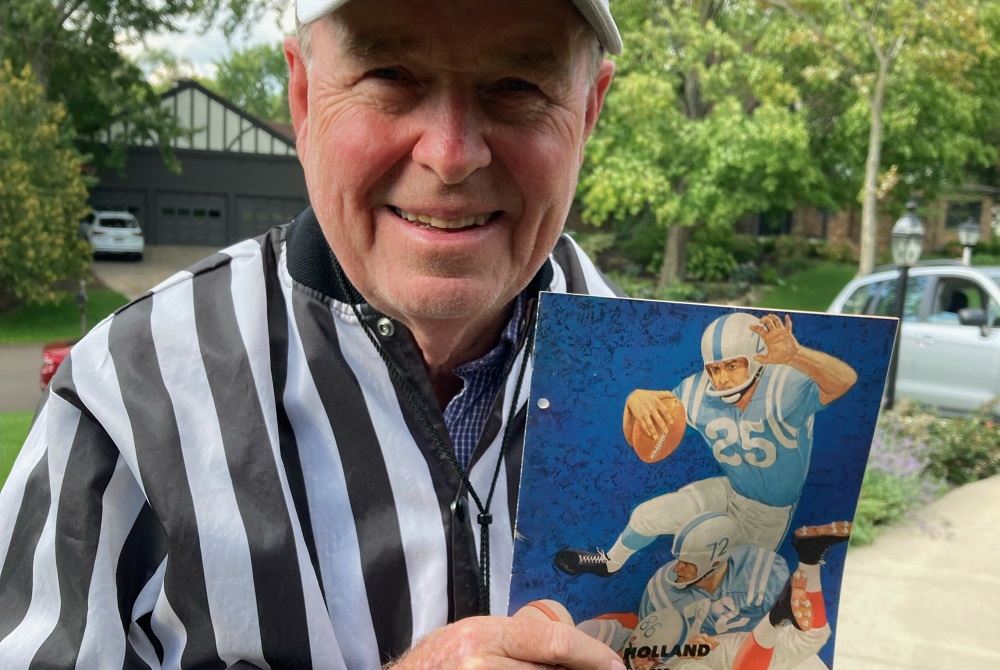

GRAND RAPIDS – All Tom Essenburg could think of was the warmth of a waiting bus.

Five decades later, that's what Essenburg – then a senior defensive back at Holland High School – remembers most about a stormy Friday night before 2,100 thoroughly drenched fans at Riverview Park. He recalls having a solid night from his position in the Dutch secondary. He remembers a fourth-quarter downpour, Holland eventually winning the game and trudging wearily through the lakes of mud to the team's bus.

But what never dawned on Essenburg until much later was that he had been the first to accomplish something only three defenders in the history of Michigan high school football have ever done:

Intercept five passes in a single game.

"I knew after the game that I had a bunch of them, but (at the time) we were in a 0-0 game and my mind was on just don't get beat (on a pass) and we lose 7-0," he said of the Sept. 21, 1962, contest against Muskegon Heights.

It wasn't until the next morning's story in the Holland Evening Sentinel that Essenburg grasped what exactly had happened. He didn't realize until then that he had picked off five passes in all, including two over the last 1:52 that sealed a 12-0 win over Muskegon Heights. One of the interceptions went for a 37-yard touchdown, which Essenburg does vividly remember.

"I remember thinking to myself that I had to score," said Essenburg, who has been involved with high school sports in one fashion or another for more than 60 years. "There was a Muskegon Heights guy who had the angle on me and I pretty much thought I was going to get tackled, but I got in there."

Essenburg's recollection of the first three interceptions is a bit hazy after 61 years, but the next day's newspaper account pointed out one amazing fact. The Muskegon Heights quarterback had only attempted six passes during the entire game, with five of them winding up in the hands of the 5-foot-8, 155-pound Essenburg – who had never intercepted a single pass before that night. He would later intercept two more in the season finale against Grand Rapids Central.

It wasn't until the middle 1970s that Essenburg began wondering where the five-interception performance ranked among Michigan High School Athletic Association records. What he remembers most about the game was the overwhelming desire to find warmth and dry out.

"I just wanted to get to the bus and get warm. We were all soaked," he said. "For me it was like, 'OK, game over.' I was just part of the story."

Curiosity, however, eventually got the better of Essenburg. A decade later he contacted legendary MHSAA historian Dick Kishpaugh, who in an attempt to confirm the five interceptions, wrote to Muskegon Heights coach Okie Johnson, who quickly verified the mark.

It turns out that at the time in 1962, nobody had even intercepted four passes in a game. And since Essenburg's record night, only Tony Gill of Temperance Bedford on Oct. 13, 1990, and then Zach Brigham of Concord on Oct. 15, 2010, have matched intercepting five passes in one game.

Three years after Essenburg's special night, Dave Slaggert of Saginaw St. Peter & Paul became the first of 17 players to intercept four passes in a game.

Essenburg laughs about it now, but his five interceptions didn't even earn him Player of the Week honors from the local Holland Optimist Club. Instead, the club inexplicably gave the honor to a defensive lineman.

Essenburg laughs about it now, but his five interceptions didn't even earn him Player of the Week honors from the local Holland Optimist Club. Instead, the club inexplicably gave the honor to a defensive lineman.

It was that last interception Essenburg cherishes the most. His fourth with 1:52 remaining at the Holland 17-yard line had set up a seven-play, 83-yard drive that snapped a scoreless tie. Then on Muskegon Height's next possession, Essenburg grabbed an errant pass and raced 37 yards down the sideline to seal the game with 13 seconds left.

In those days, running games dominated high school football and defensive backs were left virtually on their own, Essenburg said.

"I kept thinking don't let them beat you, don't let them beat you. No one can get beyond you. In those days, once a receiver got in the secondary, they were gone," said Essenburg, who describes himself as a capable defender but no star.

"I wasn't great, but I guess I was pretty good for those days," he said. "I'm proud that I'm in the record book with a verified record."

Essenburg's Holland High School career, which also included varsity letters in tennis and baseball, is part of a lifelong association with prep sports. After playing tennis at Western Michigan, he became Allegan High School's athletic director in 1971 while coaching the tennis team and junior varsity football from 1967-73.

But he's most proud of being a member of the West Michigan Officials Association for the last 47 years. During that time, Essenburg estimates he's officiated more than 400 varsity football games and nearly 1,000 freshman and junior varsity contests. In all, he's worked 83 playoff games, including six MHSAA Finals, the most recent in 2020 at Ford Field. An MHSAA-registered official for 52 years total, he's also officiated high school softball since 1989.

Essenburg also worked collegiately in the Division III Michigan Intercollegiate Athletic Association and NAIA for 35 years, including officiating the 2005 Alonzo Stag Bowl.

Essenburg said the one thing that's kept him active in officiating is being a small part of the tight community and family bonds that make fall Friday nights special.

"I enjoy being part of high schools' Friday night environment," he said. "All that is so good to me, especially the playoffs. It's the small schools and being part of community. I used to say it was the smell of the grass, but now, of course, it's turf.

"I can't play anymore, but I can play a part in high school football in keeping the rules and being fair to both teams. That's what I want to be part of."

While it can be argued high school football now is a far cry from Essenburg's era, he believes his even-tempered attitude serves him well as an official. It's also the first advice he would pass along to young officials.

"My makeup is that I don't get rattled," he said. "Sure, I hear things, but does it rattle me? No. I look at it as part of the game. My goal is to be respected.

"I've never once ejected a coach. It's pretty much just trying to be cool and collected in talking to coaches. It's like, 'OK Coach, You've had your say, let's go on."

While Essenburg is rightly proud of his five-interception record, he believes the new days of quarterbacks throwing two dozen times in a game will eventually lead to his mark falling by the wayside. And that's fine, he said.

"It'll get beaten, no question. It's just a matter of when," he said. "Quarterbacks are so big now, like 6-4, 200 pounds, and they are strong-armed because of weight programs. They throw lots of passes now, so there's no doubt it's going to happen."

Until Essenburg is erased from the record book, he'll take his satisfaction from his connection with Friday Night Lights.

"I love high school sports and being with coaches and players," he said. "My goal was once to work for the FBI or be a high school coach, but now I want to continue working football games on Friday nights until someone says no more."

PHOTOS (Top) Tom Essenburg holds up a copy of the program from the 1962 game during which he intercepted a record five passes for Holland against Muskegon Heights. (Middle) Essenburg, left, and Al Noles officiate an Addix all-star game in Grand Rapids. (Photos courtesy of Tom Essenburg.)